|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 39(5); 2024 > Article |

|

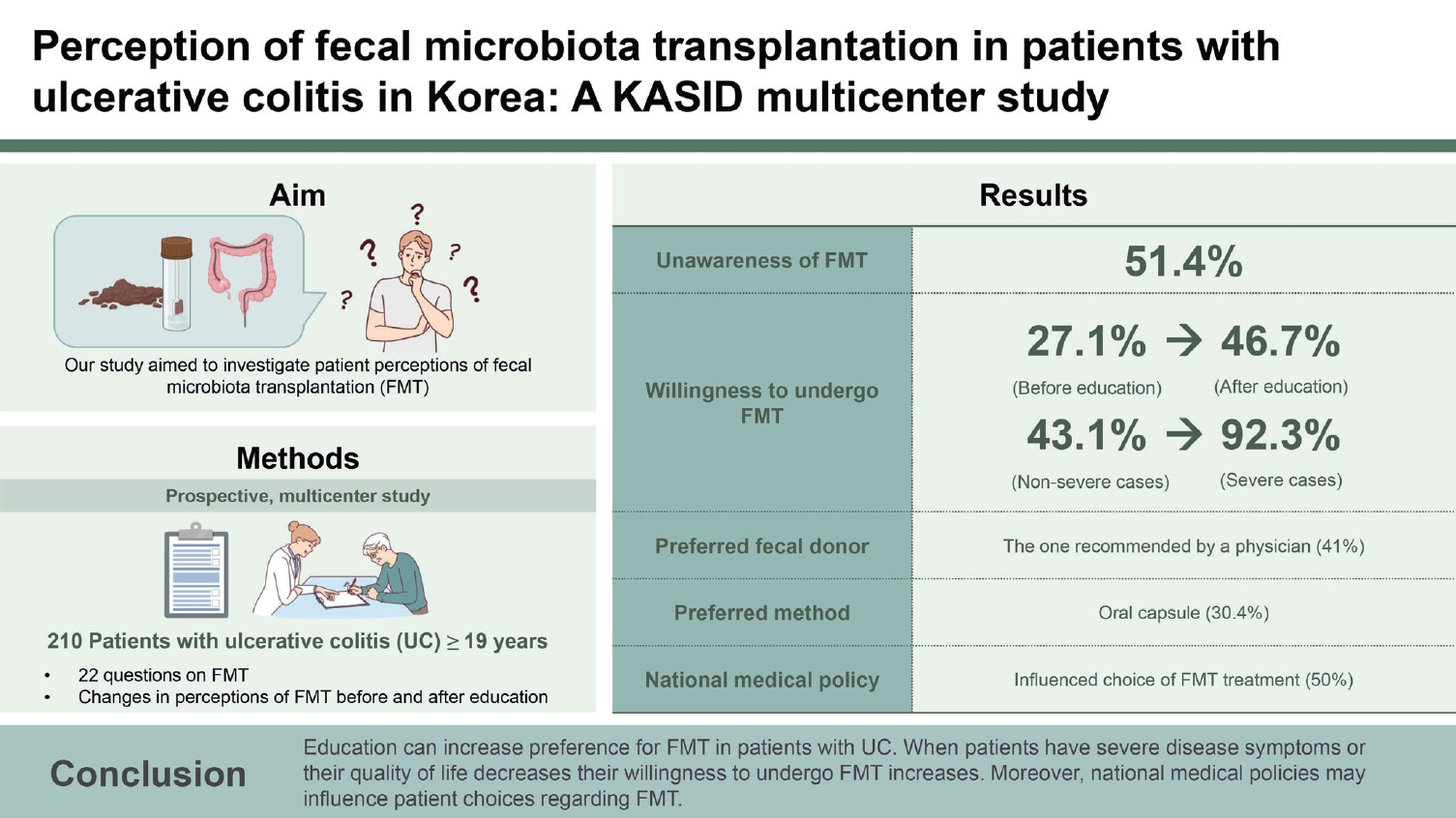

Abstract

Background/Aims

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a promising therapy for inducing and maintaining remission in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). However, FMT has not been approved for UC treatment in Korea. Our study aimed to investigate patient perceptions of FMT under the national medical policy.

Methods

This was a prospective, multicenter study. Patients with UC Ōēź 19 years of age were included. Patients were surveyed using 22 questions on FMT. Changes in perceptions of FMT before and after education were also compared.

Results

A total of 210 patients with UC were enrolled. We found that 51.4% of the patients were unaware that FMT was an alternative treatment option for UC. After reading the educational materials on FMT, more patients were willing to undergo this procedure (27.1% vs. 46.7%; p < 0.001). The preferred fecal donor was the one recommended by a physician (41.0%), and the preferred transplantation method was the oral capsule (30.4%). A large proportion of patients (50.0%) reported that the national medical policy influenced their choice of FMT treatment. When patients felt severe disease activity, their willingness to undergo FMT increased (92.3% vs. 43.1%; p = 0.001).

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has gained increasing importance for treating recurrent or refractory Clostridioides difficile infections (CDI). Although immunomodulators, biological agents, and small-molecule drugs are mainly used to treat inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) such as ulcerative colitis (UC) and CrohnŌĆÖs disease [1-5], FMT is a promising therapy for inducing and maintaining remission in patients with UC [6,7]. In Korea, FMT first began in 2013 for patients with CDI but was not approved for treating UC. The reimbursement of FMT is not covered by the national health insurance.

In several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [8-11] and a meta-analysis of RCTs conducted on 140 patients with UC [12], FMT significantly increased the clinical remission rate. Even when steroid dependence was observed in patients with UC using classical treatments or biological agents, long-term use of FMT showed a good clinical response (> 90%) and endoscopic remission (up to 80%) [13].

Many studies have investigated the perception of FMT in Western countries [14-18]. Recently, a survey on physiciansŌĆÖ perceptions of FMT was conducted in South Korea [19]. In this study, most of the 107 physicians who responded to the survey had experience performing FMT; the most common indication for FMT was CDI. In Korea, FMT as a new therapeutic option for patients with UC remains in its infancy. Therefore, we investigated the recognition of FMT in patients with UC and their attitudes toward this procedure for UC treatment. Their preference for FMT was also assessed after receiving educational materials under the national medical policy.

This prospective study was conducted between January 2021 and December 2022 at seven university hospitals in South Korea. Patients with UC who were Ōēź 19 years of age and agreed to participate were enrolled. At the time of the survey, the patientsŌĆÖ age, sex, education and economic levels, operation history, clinical classification according to the Montreal classification at diagnosis, and disease activity at diagnosis and during the survey were recorded. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients. The study protocol was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of each facility (approval number: SCHUH 2020-01-008-001, SMC 2021-12-039).

The survey instrument was developed based on the opinions of the study group. Patients were surveyed using 22 questions on FMT. To investigate changes in the perception of FMT before and after providing educational material, three questions were asked before education, and 19 questions were asked after education. Educational materials on FMT included definitions, indications, donor selection and screening tests, efficacy for UC, and adverse events associated with FMT. The questionnaire details are presented in Table 1. The survey focused on patientsŌĆÖ perceptions of FMT. The willingness, preferred donor and method, concerns about FMT, and factors influencing the choice of FMT were investigated. The Korean version of the questionnaire and educational materials are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Quantitative variables are expressed as means, and qualitative variables are expressed as percentages. Continuous and categorical variables were compared using a two-tailed StudentŌĆÖs t-test and chi-square test, respectively. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Data management and statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 21.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

A total of 210 patients participated in this study. The mean age was 44.6 years, and males outnumbered females by 68.6%. Of the total, 170 patients had a high school or higher education level, accounting for more than 90%. More than 50% of patientsŌĆÖ households earned Ōēź $50,000. One hundred sixteen (55.3%) people were diagnosed with UC under the age of 40. At the time of the survey, 142 (71.0%) patients were in clinical remission, and 55 (27.5%) had mild to moderate disease activity. The disease period was less than 2 years for 131 people (65.8%), 2ŌĆō5 years for 35 people (17.6%), and > 5 years for 33 people (16.6%). The patient characteristics are shown in Table 2.

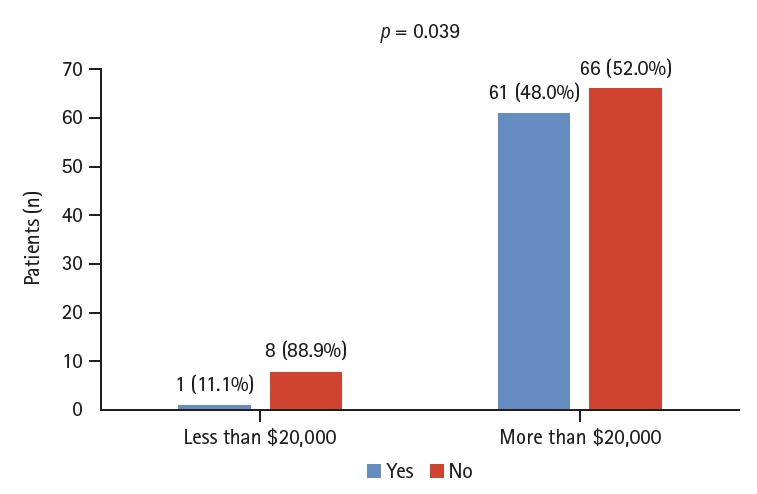

Before education, 87 (41.4%) patients had heard of FMT, and 108 (51.4%) said they had not heard of it. The questionnaire asked, ŌĆ£What would you do if you heard from other patients that UC treatment was effective after FMT?ŌĆØ The number of patients willing to try it increased from 57 (27.1%) to 130 (61.9%) (Table 1). No significant correlation was observed between educational status and perceptions of FMT (p > 0.05). In contrast, there was a significant difference in awareness of FMT based on income, from one (11.1%) patient earning < $20,000 to 61 (48.0%) earning > $20,000 (p = 0.039; Fig. 1).

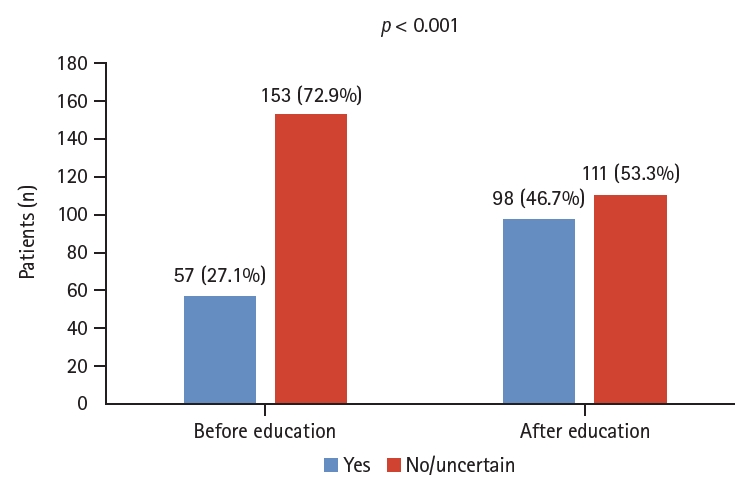

The number of people who wanted to undergo FMT before and after receiving educational materials on FMT increased significantly from 57 (27.1%) to 98 (46.7%) (p < 0.001; Fig. 2). Currently, FMT is not recognized as a formal treatment for UC in Korea, and 105 respondents (50%) reported that it affected FMT treatment decisions. In response to the survey question, ŌĆ£How would you describe your current UC disease status?ŌĆØ 13 (6.3%) patients reported severe disease (Table 1).

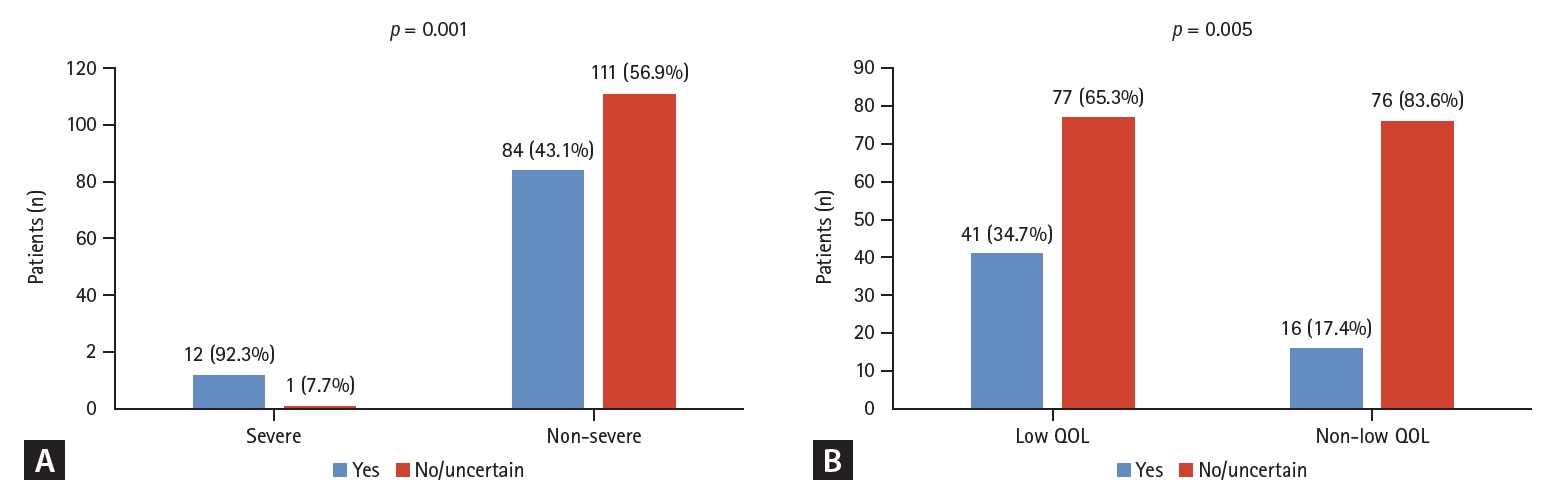

Among patients who felt disease activity was severe, 12 of 13 patients (92.3%) showed a willingness to undergo FMT, whereas, in the group that did not, 84 of 195 patients (43.1%) showed an interest in FMT (p = 0.001). Disease duration was not associated with patientsŌĆÖ willingness to undergo FMT. In the group that felt that it was challenging to live their daily lives because of UC, 41 of 118 people (34.7%) were willing to try FMT, and in the group that did not find it challenging, only 16 of 92 (17.4%) were interested in FMT (p = 0.005; Fig. 3).

The most preferred FMT donors were physician recommendations in 86 patients (41.1%), followed by family members in 84 patients (40.2%). Most patients wanted a physicianŌĆÖs recommendation or family members as donors. Freezedried capsules were the most preferred method of administering FMT in 63 patients (30.0%), followed by colonoscopy in 46 patients (21.9%). If UC worsened, the preferred treatment was new drugs in 79 patients (37.6%) and FMT in 24 (11.4%). In the case of receiving feces from anonymous healthy stool donors selected through pre-testing, 97 (46.2%) were willing to undergo FMT (Table 1).

In a survey on the most worrisome aspects of FMT, 99 patients (48.3%) answered that they were most worried about infection after FMT. Fifty-three patients (25.9%) were concerned it would not have a therapeutic effect. Safety and treatment efficacy were the most concerning aspects for patients with UC who chose FMT as a therapeutic option. The primary concern regarding the safety of FMT was that it would worsen UC, with 64 patients (31.4%) stating this, followed by 63 (30.1%) who were concerned that the donor stool may not be thoroughly screened for infectious diseases (Table 1).

This study aimed to investigate perceptions of FMT in patients with UC and to identify the association between attitudes toward FMT and education, national medical policy, and disease severity. To the best of our knowledge, no survey has investigated the various factors related to attitude changes toward FMT.

Recently, FMT has been increasingly used as a CDI treatment and is recognized as a standard treatment, especially for recurrent CDI [20-22]. The effect of FMT on UC has also been confirmed in Western studies [8-13]. As a result, awareness among physicians and patients has increased and is being implemented in many cases. Nonetheless, a Western study reported that 53.5% of patients with CDI and UC were unaware of FMT [14]. Similarly, in our study, a large proportion of patients with UC (51.4%) were unaware of FMT as a therapeutic option. This shows that the awareness of FMT remains low among patients with UC in Korea. Significantly more patients were positive toward FMT after the educational materials were provided. Western studies have reported similar results [14,17]. This suggests that educational materials, including the current evidence, can change attitudes toward new therapeutic options. Physicians must cultivate patient treatment knowledge by providing information on therapeutic options. However, the latest American Gastroenterological Association guidelines suggest against using conventional FMT in patients with UC, except in the context of clinical trials [23]. Although our study showed that patient education can increase the preference for FMT in patients with UC, physicians should consider that FMT for UC can be used outside of a clinical trial when no comparable or satisfactory alternative treatment options are available. Further large, population-based, well-designed studies are needed to establish the long-term efficacy and safety of FMT for treating UC.

Notable results were observed regarding the disease activity and quality of life. Up to 93% of the patients who experienced severe disease activity were willing to receive FMT. Compared with the group who did not experience severe disease activity, the willingness to undergo FMT was significantly higher (92.3% vs. 43.1%, p = 0.001). Willingness to undergo FMT was significantly increased in patients who thought it challenging to live a normal life due to UC compared with those whose quality of life was not affected (34.7% vs. 17.4%, p = 0.005). This suggests that the desire for and acceptance of new therapeutic options such as FMT is higher in patients with higher disease severity and lower quality of life. In addition, 50% (105/210) of the respondents said that their decisions were affected because FMT was not approved as a treatment option for IBD in Korea. This suggests that national medical policies may foster a reluctance to select appropriate therapeutic options.

Evidence regarding the donor type best suited for FMT in patients with UC is lacking. In our study, a similar number of patients preferred donor selection regardless of their physicianŌĆÖs recommendation (41.1%) or that of family members (40.2%). Safety (e.g., worse UC and infection) and treatment efficacy of FMT in patients with UC were evaluated in our study. The future implementation of FMT in Korean patients with UC implies that shared decision-making will play an important role in donor and treatment selection.

Our study has several advantages. First, this was a multicenter prospective survey that enrolled 210 patients with UC. Therefore, the results may be generalizable. Second, this study is the first to investigate the factors related to attitude changes toward FMT. Third, this survey suggests that patients with UC are interested in FMT as a new therapeutic option and would like it to become available. However, this study has some limitations. First, an unvalidated questionnaire was used. Secondly, there were some missing values in the questionnaire, which made the study less reliable. Despite these limitations, our results suggest that many factors influence Korean patients with UCŌĆÖs perceptions of and attitudes toward FMT and can be changed through education.

In conclusion, FMT awareness remains low among patients with UC in Korea. The preference for FMT in patients with UC can be increased through patient education. Attitude changes concerning FMT were associated with disease severity as perceived by the patient and the national medical policy.

1. More than half of the surveyed patients were unaware that FMT was an alternative treatment option for UC.

2. Education can increase the preference for FMT in patients with UC.

3. Patient attitudes towards FMT were influenced by national medical policy, as well as the disease severity and quality of life perceived by the patients.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Jebyung Park: investigation, data curation, formal analysis, validation, writing - original draft; Sung Noh Hong: investigation, data curation, validation; Hong Sub Lee: resources, investigation, data curation; Jongbeom Shin: resources, investigation, data curation; Eun Hye Oh: resources, investigation, data curation; Kwangwoo Nam: resources, investigation, data curation; Gyeol Seong: resources, investigation, data curation; Hyun Gun Kim: conceptualization, methodology, resources, investigation, data curation, writing - review & editing; Jin-Oh Kim: investigation, data curation; Seong Ran Jeon: conceptualization, writing - review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition

Figure┬Ā3.

Factors related to attitude changes after education. The willingness to undergo fecal microbiota transplantation according to disease severity (A) and quality of life (QOL) (B) perceived by the patient.

Table┬Ā1.

Questionnaire results (n = 210)

Table┬Ā2.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | UC (n = 210) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 44.6 |

| Male | 144 (68.6) |

| Education level | |

| ŌĆāLess than middle school | 17 (9.1) |

| ŌĆāHigh school graduation | 68 (36.4) |

| ŌĆāCollege degree | 88 (47.1) |

| ŌĆāPostgraduate education | 14 (7.5) |

| Household income | |

| ŌĆāLess than $20,000 | 11 (5.2) |

| ŌĆā$20,000ŌĆō$50,000 | 38 (20.3) |

| ŌĆā$50,000ŌĆō$70,000 | 29 (15.5) |

| ŌĆā$70,000ŌĆō$100,000 | 41 (21.9) |

| ŌĆāMore than $100,000 | 27 (14.4) |

| ŌĆāDo not wish to disclose | 41 (21.9) |

| Previous surgery | 19 (9.0) |

| Duration of disease (yr) | |

| ŌĆā< 2 | 131 (65.8) |

| ŌĆā2ŌĆō5 | 35 (17.6) |

| ŌĆā> 5 | 33 (16.6) |

| Age at diagnosis, mean years | |

| ŌĆāA1 (< 17 years) | 5 (2.4) |

| ŌĆāA2 (17ŌĆō40 years) | 111 (52.9) |

| ŌĆāA3 (> 40 years) | 93 (44.3) |

| UC extent (at diagnosis) | |

| ŌĆāE1 (proctitis) | 89 (42.4) |

| ŌĆāE2 (left-sided) | 52 (25.6) |

| ŌĆāE3 (extensive) | 62 (30.5) |

| Disease activitya) (at diagnosis) | |

| ŌĆāClinical remission | 11 (6.7) |

| ŌĆāMild activity | 62 (37.6) |

| ŌĆāModerate activity | 82 (49.7) |

| ŌĆāSevere activity | 10 (6.1) |

| Disease activitya) (at survey) | |

| ŌĆāClinical remission | 142 (71.0) |

| ŌĆāMild activity | 33 (16.5) |

| ŌĆāModerate activity | 22 (11.0) |

| ŌĆāSevere activity | 3 (1.5) |

| Concomitant medications (at survey) | |

| ŌĆā5-ASA | 57 (27.1) |

| ŌĆā5-ASA + topical 5-ASA | 55 (26.2) |

| ŌĆāTopical 5-ASA | 32 (15.2) |

| ŌĆā5-ASA + AZA | 16 (7.6) |

| ŌĆāNo specific medication | 9 (4.3) |

| ŌĆā5-ASA + steroid | 8 (3.8) |

| ŌĆā5-ASA + topical 5-ASA + biologics | 6 (2.9) |

| ŌĆāBiologics | 6 (2.9) |

| ŌĆā5-ASA + steroid + AZA | 4 (1.9) |

| ŌĆā5-ASA + topical 5-ASA + AZA | 4 (1.9) |

| ŌĆā5-ASA + AZA + biologics | 3 (1.4) |

| ŌĆāAZA | 2 (1.0) |

| ŌĆā5-ASA + biologics | 2 (1.0) |

| ŌĆāAZA + biologics | 2 (1.0) |

| ŌĆā5-ASA + topical 5-ASA + steroid | 1 (0.5) |

| ŌĆā5-ASA + topical 5 ASA + AZA + biologics | 1 (0.5) |

| ŌĆāSteroid | 1 (0.5) |

| ŌĆāSteroid + biologics | 1 (0.5) |

REFERENCES

1. Murray A, Nguyen TM, Parker CE, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;8:CD000544.

2. Mantzaris GJ. Thiopurines and methotrexate use in IBD patients in a biologic era. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2017;15:84ŌĆō104.

3. Jun YK, Koh SJ, Myung DS, et al. Infectious complications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: the results of a multinational web-based survey in the 8th Asian Organization for CrohnŌĆÖs and Colitis meeting. Intest Res 2023;21:353ŌĆō362.

4. Magro F, Cordeiro G, Dias AM, Estevinho MM. Inflammatory bowel disease - non-biological treatment. Pharmacol Res 2020;160:105075.

5. Al-Bawardy B, Shivashankar R, Proctor DD. Novel and emerging therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:651415.

6. Tariq R, Loftus EV Jr, Pardi D, Khanna S. Durability and outcomes of fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection in patients with moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease. Intest Res 2024;22:208ŌĆō212.

7. Arora U, Kedia S, Ahuja V. The practice of fecal microbiota transplantation in inflammatory bowel disease. Intest Res 2024;22:44ŌĆō64.

8. Moayyedi P, Surette MG, Kim PT, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2015;149:102ŌĆō109.e6.

9. Rossen NG, Fuentes S, van der Spek MJ, et al. Findings from a randomized controlled trial of fecal transplantation for patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2015;149:110ŌĆō118.e4.

10. Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389:1218ŌĆō1228.

11. Costello SP, Hughes PA, Waters O, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on 8-week remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:156ŌĆō164.

12. Paramsothy S, Paramsothy R, Rubin DT, et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:1180ŌĆō1199.

13. Sood A, Mahajan R, Juyal G, et al. Efficacy of fecal microbiota therapy in steroid dependent ulcerative colitis: a real world intention-to-treat analysis. Intest Res 2019;17:78ŌĆō86.

14. Zeitz J, Bissig M, Barthel C, et al. PatientsŌĆÖ views on fecal microbiota transplantation: an acceptable therapeutic option in inflammatory bowel disease? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;29:322ŌĆō330.

15. Roggenbrod S, Schuler C, Haller B, et al. [Patient perception and approval of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) as an alternative treatment option for ulcerative colitis]. Z Gastroenterol 2019;57:296ŌĆō303German.

16. Gundling F, Roggenbrod S, Schleifer S, Sohn M, Schepp W. Patient perception and approval of faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) as an alternative treatment option for obesity. Obes Sci Pract 2018;5:68ŌĆō74.

17. Kahn SA, Vachon A, Rodriquez D, et al. Patient perceptions of fecal microbiota transplantation for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:1506ŌĆō1513.

18. Madar PC, Petre O, Baban A, Dumitrascu DL. Medical studentsŌĆÖ perception on fecal microbiota transplantation. BMC Med Educ 2019;19:368.

19. Gweon TG, Lee YJ, Yim SK, et al. Recognition and attitudes of Korean physicians toward fecal microbiota transplantation: a survey study. Korean J Intern Med 2023;38:48ŌĆō55.

20. Johnson S, Lavergne V, Skinner AM, et al. Clinical practice guideline by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA): 2021 focused update guidelines on management of Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e1029.

21. Bang BW, Park JS, Kim HK, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for refractory and recurrent clostridium difficile infection: a case series of nine patients. Korean J Gastroenterol 2017;69:226ŌĆō231.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement 1

Supplement 1 Print

Print