|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

Background/Aims

We aimed to assess the validity of the Korean translated version of the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) in determining the frailty status in geriatric outpatients.

Methods

The records of 123 ambulatory outpatients who had undergone CFS and comprehensive geriatric assessments (CGAs) including measurements for the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) frailty scale and the frailty index (CGA-FI) were analyzed. Correlations between CFS, CHS frailty scale, and CGA-FI were assessed. The ability of CFS to classify frailty status was calculated using the CHS frailty scale and CGA-FI as references.

Results

The mean CFS score was 3.2 in the study population, with a mean age of 77.49 years (45.5% men). Individuals with higher CFS scores were older, had a greater burden of chronic diseases, and worse daily functions and cognitive performance. CFS scores positively correlated with CGA-FI (B = 0.78, p < 0.001) and CHS frailty scale (B = 0.67, p < 0.001) scores. For CFS, C-statistics to classify frailty by CGA-FI and CHS scale were 0.905 and 0.826, respectively. The cut-off value of CFS Ōēź 4 maximized YoudenŌĆÖs J to classify frailty by both the CHS scale and CGAFI.

Frailty, a common geriatric syndrome that is closely related to human aging, is defined as a state of decreased physiological reserve and increased vulnerability to internal or external stressors [1]. Several studies have shown the impacts of frailty on the outcomes of fall, functional decline, institutionalization, and mortality in both community and hospital settings [2,3], with growing research interests in assessing frailty in various clinical conditions even among specialties other than geriatrics [4]. By virtue of its outcome prediction ability, frailty is factored in the decision-making processes of several clinical conditions [5,6]. Furthermore, recent studies have shown the dynamic characteristics of frailty [7] and suggested that frailty can be improved with appropriate intervention strategies [8]. Therefore, frailty is a crucial clinical outcome measure as well as an outcome predictor.

Identifying frailty status can be the first step to provide centered, tailored care for older adults through multidimensional assessment and intervention [9,10]. However, frailty statuses have been not commonly assessed in most acute hospitals, including those in Korea. In acute care settings, performing comprehensive geriatric assessments (CGAs) for older patients is less feasible as CGAs frequently take > 30 minutes for a single patient. To address this unmet need, several screening measures of frailty for older adults have been developed and validated [11-14]. Among these instruments, the ones requiring physical performance assessments might be less applicable for acute hospital settings where patients experience sudden deconditioning due to acute illnesses. Moreover, questionnaires validated in community-dwelling populations or primary care settings might be less reliable for identifying the vulnerable populations in acute or chronic hospitals.

The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), a simple tool with brief descriptors and pictographs, to track frailty index, was developed to facilitate a broader application of frailty in real-world clinical practices [15]. Following an initial validation of outcome prediction abilities in a community-dwelling population [15], numerous studies have employed this scale and found clinical validity in its outcome prediction, in settings ranging from long-term care facilities to emergency departments [16]. Hence, CFS has been used in wide range of clinical settings in western countries, in clinical decision making and outcome prediction [17-19]. Furthermore, CFS has been even suggested as a measure in evaluating older people or allocating scarce health resource in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [5,17]. Despite its validity and wide-adaptability, to the best of our knowledge, the screening value of the CFS has been not yet reported in the Korean population. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to assess the screening ability of the CFS for frailty determined by two widely used measures of frailty, the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) frailty scale and the CGA-frailty index (CGA-FI), in outpatients of a geriatric clinic in a tertiary hospital in Korea.

This was a cross-sectional analysis that used records of 123 outpatients who had undergone CFS and CGA assessments between February 2019 and April 2020 in a geriatric clinic at Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. We included community-dwelling patients who were ambulatory with or without walking aids and were able to communicate with the examiners and agreed to participate in the prospective registry of CGA and aging biomarker study. Further, we excluded patients with apparent life expectancies of less than 1 year due to malignancies, patients with symptomatic heart failure or end-stage renal disease, patients unable to walk without assistance, and patients with cognitive dysfunction who could not follow the instructions of the physical performance tests.

We used a 9-score version of the original CFS (version 2.0) that translated into Korean by English-proficient geriatrician and reviewed by another clinical geriatrician who had clinical experience in both Korean and United States, and an independent bilingual geriatrician educated in United States (Supplementary Table 1). After this process, words and descriptions were further reviewed for cultural aspects of Korean older people and clinical usability, by clinical geriatricians and nurses. CFS was administered by the experienced nurses in the geriatric clinic by interviewing the patients and their family members, during regular CGA. Most probable state of general health status during recent 1 to 2 weeks was selected in the scale.

The CGA included the common geriatric domains of comorbidities, fall history, polypharmacy, nutrition risk, mobility, cognition, and physical performance. The comorbidities were identified by reviewing medical records and through patient interviews. Polypharmacy was defined as the usage of five or more different medications per day. Mobility and basic physical activities were assessed using items suggested by Rosow and Breslau [20] and Nagi [21], respectively. The presence of fall history in the previous 12 months was assessed. Cognitive function was assessed by the Korean version of the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE), and cognitive impairment was defined as an MMSE score of less than 24 [22]. The participants were interviewed on difficulties in performing activities of daily living (ADL) functions (dressing, washing, bathing, eating, moving, and using the bathroom) and instrumental ADL functions (using transportation, using phones, buying groceries, managing medications, managing finances, preparing foods, performing basic household chores, and washing clothes). Individuals with impairments in 1 or more items were regarded to have disabilities in ADL or IADL. The grip strength of the dominant side was measured by a hydraulic dynamometer (Jamar, Patterson Medical, Warrenville, IL, USA). Four-meter usual gait speed and 5-time chair stand test were assessed using an electronic SPPB toolkit (eSPPB, Dyphi Inc., Daejeon, Korea). From these parameters of CGA, we established a 50-item CGA-FI from the components of CGA (Supplementary Table 2) that had been established in a standardized manner and used in other studies [4,23,24]. The sums of the scores of each item were calculated and divided by the total number of available items (50 if no items were missed), to produce CGA-FIs ranging from 0 (best) to 1 (worst). We considered frailty indices of 0.25 and higher as frail [3].

The frailty phenotype was evaluated by the CHS frailty scale [25] that comprised the following items: (1) exhaustion determined by a patient health questionnaire-2 screening test total score > 2 [26]; (2) low physical activity defined as a weekly activity amount < 494.65 kcal for men and < 283.50 kcal for women using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire [27]; (3) low grip strength by the grip strength of the lowest quintile corresponding to sex and body mass index [27]; (4) slowness by the gait speed of the lowest quintile corresponding to sex and height [27]; and (5) unintentional weight loss of > 4.5 kg in the previous 12 months. For the CHS frailty score, the number of positive items was calculated and individuals with CHS frailty scores of 3 and higher were considered to be frail.

Independent t test and chi-square test or FischerŌĆÖs exact test were used to compare the characteristics between the patients with CFS scores < 4 (lower CFS group) and Ōēź 4 (higher CFS group), by taking into account the distribution of the CFS scores in the study population. Additionally, skewness tests and histograms were used to assess the distributions of frailty measures in the study population. We adopted Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments terms of construct and criterion validity to analyze and describe the validity of CFS in assessing the frailty status [28]. Using linear regression analyses, correlations between the CFS scores and geriatric parameters or the items of the CHS frailty scale were assessed, and standardized beta [B] was calculated as the regression coefficient. The correlations between the CFS scores, CHS frailty score, and frailty index were evaluated using linear regression analysis, and B was calculated as the regression coefficient. C-statistics were calculated for CFS scores to determine frailty by the CHS frailty scale and the frailty index using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Additionally, sensitivities and specificities for specific CFS scores to classify frailty by the CHS frailty scale and frailty index were calculated. To suggest cut-offs of CFS scores to suspect frailty, we calculated YoudenŌĆÖs J (sensitivity + specificity-1). We considered two-sided p values < 0.05 to be statistically significant and used Stata version 16.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) for analyses.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (2018-0673) and complied with the ethical rules for human experimentation stated in the Declaration of Helsinki [29]. Written informed consent was acquired from the participants or their proxies.

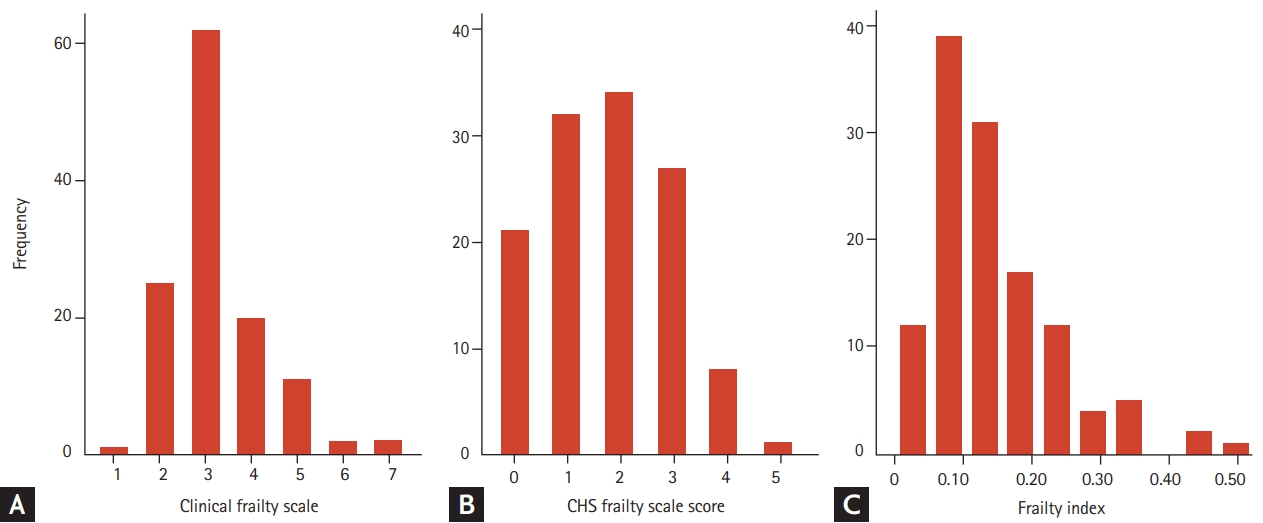

In the study population of 123 individuals, the mean age was 77.49 years, and 56 individuals (45.5%) were men. The mean ┬▒ standard deviation CFS score was 3.2 ┬▒ 1.1 and the mean frailty index was 0.15 ┬▒ 0.09. Most of the items included in the frailty index were present for the 123 individuals, data of physical activity and MMSE were available in 119 people, and those of BMI and five times chair stand test were available in 122. The mean CHS frailty scale score in the study population was 1.8 ┬▒ 1.2. By skewness test, both CFS scores and frailty index were right-skewed (both p < 0.001) whereas CHS frailty scale scores were not skewed (p = 0.366). Distributions of these three frailty measures are shown in Fig. 1.

The study population was divided into two groups (CFS score < 4 and Ōēź 4), considering the mean value of CFS. As shown in Table 1, individuals with higher CFS scores tended to be older, were more likely to be women, had a greater burden of chronic diseases, had worse daily functions and cognitive performances, and higher frailty indices and CHS frailty scale scores.

By linear regression, CFS scores significantly correlated with the geriatric parameters of ADL (B = 0.54, p < 0.001), IADL (B = 0.64, p < 0.001), MMSE score (B = 0.38, p < 0.001), and the number of chronic diseases (B = 0.34, p < 0.001). Additionally, CFS scores significantly correlated positively with the CHS frailty scale items of exhaustion (B = 0.40, p < 0.001), low physical activity (B = 0.53, p < 0.001), slow gait speed (B = 0.43, p < 0.001), and weakness (B = 0.51, p < 0.001). However, the correlation between the CFS scores and weight loss was not significant (B = 0.09, p = 0.342).

Fourteen and thirty-six individuals were frail, as determined by the CGA-FI and CHS frailty scale respectively. By linear regression, CFS scores correlated with CGA-FI (B = 0.78, p < 0.001) and CHS frailty scale scores (B = 0.67, p < 0.001). Corresponding distributions of CGA-FI and CHS frailty scale scores are shown in Fig. 2. The associations of CFS scores with CGA-FI and CHS frailty scale scores remained significant with age and sex introduced as covariables (B = 0.72, p < 0.001; and B = 0.60, p < 0.001, respectively).

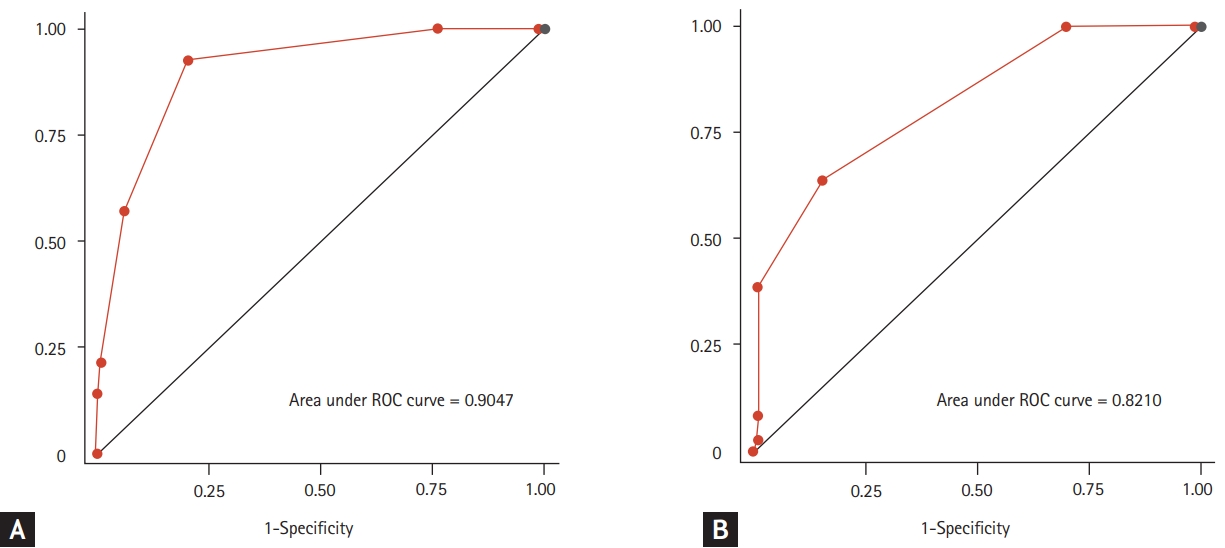

ROC analysis was used to assess the discrimination ability of CFS for classifying frailty statuses (Fig. 3). For CFS, the C-statistics to classify frailty by CGA-FI and CHS scale were 0.905 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.833 to 0.977) and 0.826 (95% CI, 0.854 to 0.897), respectively. The sensitivity and specificity for each value of CFS are shown in Table 2, and the cut-off value of CFS score Ōēź 4 maximized YoudenŌĆÖs J to classify frailty by both the CHS scale and CGA-FI.

In this cross-sectional study, we found that the CFS was correlated with geriatric parameters and two measures of frailty, the CHS frailty scale reflecting the frailty phenotype and CGA-FI reflecting the deficit accumulation model, in Korean outpatients who visited a geriatric clinic. Moreover, the discrimination ability of CFS to classify the frailty status was excellent for the frailty phenotype and outstanding for the frailty index [30]. To the authorsŌĆÖ knowledge, this study is the first to report the clinical validity of the Korean translated version of the CFS.

Despite numerous efforts to develop valid and feasible screening instruments for frailty, instruments have distinct drawbacks in clinical use. Screening questionnaires are usually validated in community-based studies rather than in acute or chronic care situations for older adults with complex care needs [14], and they might not be suitable to capture the diverse spectrum of disabilities and comorbidities. For instance, the question about loss of body weight to screen the risk of malnutrition can be only effective if the person is in the course of losing weight, and it might not be able to capture an advanced frailty status with already decreased lean mass. Although physical performance measures can be assessed objectively and are excellent in determining the frailty status with high prediction ability for adverse outcomes in older adults [31], issues exist due to the dynamic range of tools and feasibilities in applying them in varying circumstances of real-world clinical practice. For example, usual gait speed and the timed up and go test are excellent to screen the vulnerable population in primary care or community setting [32-34]; however, these examinations are less feasible in acutely ill patients with tethers (e.g., intravenous access lines, urinary catheters, and endotracheal tubes) or unstable vital signs. Additionally, these physical performance measures are less likely to provide additional information for patients with apparent limitations in mobility both in acute and chronic care settings [35].

This study was performed to probe the possibility of using CFS in a Korean tertiary hospital for detecting and managing frailty in our hospital with the CFS as an initial screening measure. As a tool validated in various environments including emergency departments, intensive care units, and chronic care facilities, the authors believe that the CFS can be used as a tool of prognostication and a screening measure to identify individuals who are susceptible to develop complications in acute care settings [5]. Furthermore, with the rising evidence supporting the clinical efficacy and the cost-effectiveness of the CGA in acutely admitted patients [36], the CFS can be used as an initial rapid-screening test to identify populations who might be benefited from CGA and downstream domain-specific, patient-centered interventions to improve the clinical outcomes of older patients with complex care needs [10].

The adoption of the CFS can be especially valuable as a functional assessment measure at care transition in hospitals, while there is still a paucity of literature showing real world adoption of CFS in Korea in this setting. In older patients, the interactions between underlying diseases, disabilities, and physical or cognitive performance affect not only care needs in welfare aspects but also clinical outcomes. Consequently, older patients might be stranded in acute wards with unmet and unaddressed needs for functional and social issues even after the acute medical problems resolve, increasing both lengths of stays and possibilities of unwanted geriatric or iatrogenic complications. Since the CFS focuses on the spectrums of generalized functional status among older adults on top of physical performance, this instrument might be used as a facile communication tool linking medical problems and functional care needs. With researchers currently developing an electronic pathway using CFA as an initial screening measure, clinical benefits of CFS in care coordination can be evaluated further in the future. Hospital and community-based care resources, filling the current gap between medical care and welfare in older adults, and making care transitions more efficient and effective.

Since this was a cross-sectional analysis of a small number of outpatients who visited a geriatric outpatient clinic of a tertiary hospital, some limitations exist. Outcome validity could not be assessed due to the study design. Additionally, the validities of the CFS in inpatients or patients in other care settings in Korea cannot be assured by the current data. A recently published that performed in parallel with the participation of authors of the present study focusing on the outcome relevance of the CFS in acutely hospitalized patients in a different hospital may supplement the limitations of the present study [37].

In conclusion, the CFS correlated with two widely studied frailty measures, CHS frailty scale and frailty index, in ambulatory outpatients of a geriatric clinic in a Korean tertiary hospital, and was able to classify frailty status as a screening measure. As it is a simple and quick measuring tool, the CFS may alleviate the existing barriers in assessing frailty in real-world clinical practice.

1. The Korean translated version of the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) correlated with common geriatric parameters in comprehensive geriatric assessments in outpatients of a geriatric clinic.

2. The discrimination ability of the CFS to classify the frailty status was excellent for the frailty phenotype and outstanding for the frailty index.

3. As a simple and quick measuring tool, the CFS may alleviate the existing barriers in assessing frailty in real-world clinical practice

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (2018IF0413) from the Asan Institute for Life Science, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Figure┬Ā1.

Population distributions by specific scores of the clinical frailty scale (A), the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) frailty scale (B), and a histogram of the frailty index (C) in the study population.

Figure┬Ā2.

Means (bars) and standard deviations (whiskers) of the frailty index (A) and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) frailty scale scores (B) according to the clinical frailty scale scores.

Figure┬Ā3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to detect the frailty status using the clinical frailty scale with the frailty index (A) and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) frailty scale (B) as references.

Table┬Ā1.

Basic characteristics of the study population according to the CFS scores

| Characteristic | Lower CFS (CFS score < 4) | Higher CFS (CFS score Ōēź4) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 76.2 ┬▒ 6.3 | 88.8 ┬▒ 6.1 | < 0.001 |

| Male sex | 45 (51.1) | 11 (31.4) | 0.048 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.1 ┬▒ 3.4 | 22.9 ┬▒ 4.0 | 0.089 |

| Number of chronic diseases | 3.3 ┬▒ 1.5 | 4.7 ┬▒ 1.9 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 54 (61.4) | 24 (68.6) | 0.454 |

| Diabetes | 23 (26.1) | 12 (34.3) | 0.366 |

| Cancer | 9 (10.2) | 1 (2.9) | 0.279a |

| Coronary artery disease | 25 (28.4) | 6 (17.1) | 0.194 |

| ADL abnormality | 5 (5.7) | 7 (20.0) | 0.016 |

| IADL abnormality | 8 (9.1) | 17 (48.6) | < 0.001 |

| Cognitive impairment | 18 (20.5) | 15 (42.9) | 0.011 |

| CGA-FI | 0.10 ┬▒ 0.05 | 0.17 ┬▒ 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| CHS frailty scale score | 1.4 ┬▒ 1.1 | 2.8 ┬▒ 0.8 | < 0.001 |

Table┬Ā2.

Table for sensitivity and specificity by corresponding CFS scores to determine the frail status by the CGA-FI and the CHS frailty scale

REFERENCES

1. Dent E, Martin FC, Bergman H, Woo J, Romero-Ortuno R, Walston JD. Management of frailty: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Lancet 2019;394:1376ŌĆō1386.

2. Kim SW, Han HS, Jung HW, et al. Multidimensional frailty score for the prediction of postoperative mortality risk. JAMA Surg 2014;149:633ŌĆō640.

3. Jang IY, Lee E, Lee H, et al. Characteristics of sarcopenia by European consensuses and a phenotype score. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020;11:497ŌĆō504.

4. Kim DH, Afilalo J, Shi SM, et al. Evaluation of changes in functional status in the year after aortic valve replacement. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:383ŌĆō391.

5. Rockwood K, Theou O. Using the Clinical Frailty Scale in allocating scarce health care resources. Can Geriatr J 2020;23:210ŌĆō215.

6. Curtin D, Gallagher P, OŌĆÖMahony D. Deprescribing in older people approaching end-of-life: development and validation of STOPPFrail version 2. Age Ageing 2021;50:465ŌĆō471.

7. Jang IY, Jung HW, Lee HY, Park H, Lee E, Kim DH. Evaluation of clinically meaningful changes in measures of frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020;75:1143ŌĆō1147.

8. Jang IY, Jung HW, Park H, et al. A multicomponent frailty intervention for socioeconomically vulnerable older adults: a designed-delay study. Clin Interv Aging 2018;13:1799ŌĆō1814.

9. Jung HW. Visualizing domains of comprehensive geriatric assessments to grasp frailty spectrum in older adults with a radar chart. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2020;24:55ŌĆō56.

10. Lee H, Lee E, Jang IY. Frailty and comprehensive geriatric assessment. J Korean Med Sci 2020;35:e16.

11. Jung HW, Yoo HJ, Park SY, et al. The Korean version of the FRAIL scale: clinical feasibility and validity of assessing the frailty status of Korean elderly. Korean J Intern Med 2016;31:594ŌĆō600.

12. Jung HW, Kang MG, Choi JY, et al. Simple method of screening for frailty in older adults using a chronometer and tape measure in clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:157ŌĆō160.

13. Kim S, Jung HW, Won CW. What are the illnesses associated with frailty in community-dwelling older adults: the Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study. Korean J Intern Med 2020;35:1004ŌĆō1013.

14. Jung HW, Kim S, Won CW. Validation of the Korean Frailty Index in community-dwelling older adults in a nationwide Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort study. Korean J Intern Med 2021;36:456ŌĆō466.

15. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173:489ŌĆō495.

16. Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, Theou O. A scoping review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC Geriatr 2020;20:393.

17. Chong E, Chan M, Tan HN, Lim WS. COVID-19: use of the Clinical Frailty Scale for critical care decisions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:E30ŌĆōE32.

18. Chong E, Ho E, Baldevarona-Llego J, et al. Frailty in hospitalized older adults: comparing different frailty measures in predicting short- and long-term patient outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19:450ŌĆō457.

19. Moorhouse P, Mallery LH. Palliative and therapeutic harmonization: a model for appropriate decision-making in frail older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:2326ŌĆō2332.

21. Nagi SZ. An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc 1976;54:439ŌĆō467.

22. Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc 1997;15:300ŌĆō308.

23. Jang IY, Lee S, Kim JH, et al. Lack of association between circulating apelin level and frailty-related functional parameters in older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 2020;20:420.

24. Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr 2008;8:24.

25. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146ŌĆōM156.

26. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284ŌĆō1292.

27. Won CW, Lee S, Kim J, et al. Korean frailty and aging cohort study (KFACS): cohort profile. BMJ Open 2020;10:e035573.

28. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2010;19:539ŌĆō549.

29. World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ 2001;79:373ŌĆō374.

30. Mandrekar JN. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1315ŌĆō1316.

31. Jung HW, Jin T, Baek JY, et al. Functional age predicted by electronic short physical performance battery can detect frailty status in older adults. Clin Interv Aging 2020;15:2175ŌĆō2182.

32. Jeong SM, Shin DW, Han K, et al. Timed up-and-go test is a useful predictor of fracture incidence. Bone 2019;127:474ŌĆō481.

33. Jung HW, Jang IY, Lee CK, et al. Usual gait speed is associated with frailty status, institutionalization, and mortality in community-dwelling rural older adults: a longitudinal analysis of the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area. Clin Interv Aging 2018;13:1079ŌĆō1089.

34. Jung HW, Kim S, Jang IY, Shin DW, Lee JE, Won CW. Screening value of timed up and go test for frailty and low physical performance in Korean older population: the Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study (KFACS). Ann Geriatr Med Res 2020;24:259ŌĆō266.

35. Ga H, Won CW, Jung HW. Use of the Frailty Index and FRAIL-NH Scale for the assessment of the frailty status of elderly individuals admitted in a long-term care hospital in Korea. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2018;22:20ŌĆō25.

- TOOLS

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement 1

Supplement 1 Print

Print