|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 41(1); 2026 > Article |

|

Abstract

Chronic lung diseases, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and interstitial lung disease, contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality worldwide. Telemedicine has emerged as a promising approach for addressing these challenges by enabling remote patient monitoring, virtual consultations, and digital health interventions. Advances in home spirometry, wearable devices, and mobile health applications have improved early detection of disease exacerbations, medication adherence, and patient self-management of chronic lung diseases. Telerehabilitation programs have demonstrated their efficacy in enhancing exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with chronic lung diseases. Despite these advancements, challenges such as disparities in digital access, patient engagement, costs, and regulatory frameworks limit widespread adoption. As telemedicine has become an integral component of respiratory care, further research is required to optimize its implementation, evaluate long-term clinical outcomes, and ensure equitable access to all patients. This review explores the current state of telemedicine in chronic lung disease management, highlights technological innovations, and discusses future directions for enhancing its role in improving patient outcomes.

Chronic lung diseases, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and interstitial lung disease (ILD), are the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1,2]. Recent epidemiological data underscore the substantial global burden of these diseases, with approximately 450 million individuals being affected and 4 million annual deaths due to the disease being reported globally [2]. Given the high prevalence and significant healthcare resources required for its management, the economic and societal impacts of chronic lung disease are considerable [3,4]. This highlights the urgent need for targeted prevention strategies, optimized disease management approaches, and equitable access to healthcare services to mitigate their burden effectively.

Despite advancements in therapeutic options, significant challenges remain in addressing the healthcare needs of patients with chronic lung disease. Limited access to specialized care, particularly in rural and underserved regions, remains a major barrier. Moreover, the intermittent nature of conventional healthcare delivery often leads to delayed detection of disease progression and suboptimal management of exacerbations, ultimately compromising patient outcomes [5–7]. To address these accessibility issues, the integration of telemedicine into clinical practice presents a promising solution, facilitating real-time patient monitoring and personalized treatment modifications [8,9]. By eliminating geographical barriers and offering a cost-effective alternative to in-person visits, telemedicine can enhance healthcare management for chronic lung diseases [10]. The rapid expansion of telemedicine during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has further highlighted its role in ensuring the continuity of care during periods of restricted mobility [11,12].

Building on this foundation, this review aimed to (1) critically evaluate the clinical effectiveness of telehealth interventions across major chronic lung diseases; (2) assess the efficacy and accuracy of digital health tools, such as home spirometry, wearable devices, and smart inhalers; and (3) discuss key challenges in telemedicine implementation, including regulatory frameworks, digital disparities, and patient engagement strategies.

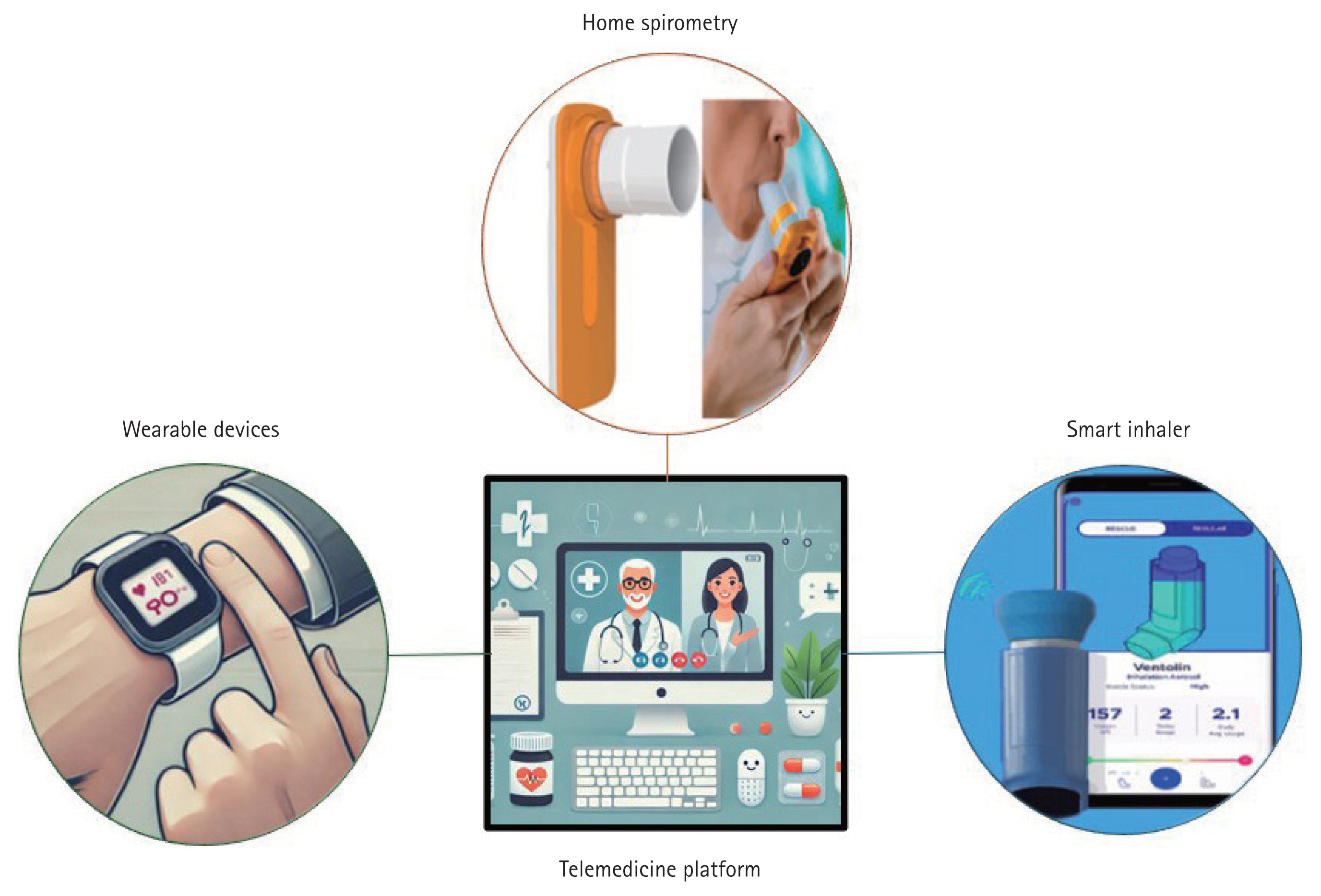

The technological foundations of telemedicine in the management of chronic lung diseases include home spirometry, wearable devices, smart inhalers, and telemedicine platforms (Table 1). Home spirometry enables remote lung function assessment for early disease detection, whereas wearable devices provide continuous physiological monitoring. Smart inhalers track the real-time use of medication to enhance patient adherence. Telemedicine platforms integrate these tools for remote monitoring, data-driven interventions, and improved patient-provider communication (Fig. 1).

Spirometry is the gold standard for diagnosing and monitoring respiratory diseases [13]; however, its access has been significantly limited, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby reducing its clinical utilization and emphasizing the need for home-based alternatives. Home spirometry allows patients to measure major lung function parameters (forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] and forced vital capacity [FVC]) without supervision, offering an alternative to clinic-based testing [13] (Table 2). Home spirometry is increasingly being used as a major clinical outcome measure in clinical trials for chronic lung diseases, including COPD [14], fibrosing ILD [15], idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) [16,17], asthma [18,19], and bronchiectasis [20]. Its role in monitoring disease severity and guiding treatment decisions has expanded, making it an essential tool in both research and clinical practice. Although the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of home spirometry in routine care and clinical trials, evidence comparing its reliability with supervised testing remains limited.

Despite variability concerns, recent studies have demonstrated that home spirometry can provide clinically acceptable results when standardized training and calibration procedures are implemented [21–24]. A meta-analysis of 28 studies, including 17 with Bland–Altman analyses, reported that home spirometry produced significantly lower FEV1 (−107 mL; limits of agreement [LoA]: −509 to 296; p < 0.001) and FVC (−184 mL; LoA: −1,028 to 660; p < 0.001) compared to supervised clinic spirometry [21]. Similarly, a post hoc analysis of two randomized clinical trials (RCTs) involving 2,857 asthma patients found treatment-related FEV1 improvements in both settings, although home measurements were less consistent and of a lower magnitude than the clinical results [22]. These discrepancies reflect technical limitations (e.g., calibration issues and lack of nose clips) and the absence of professional supervision, which may lead to suboptimal techniques and effort [24,25]. Thus, home spirometry generally yields lower and more variable results, requiring cautious interpretation in clinical and research settings.

Although concerns remain regarding the reliability of home spirometry, multiple studies have shown that when properly standardized, it can produce results comparable to clinic-based measurements [16,26–30]. Wilson et al. [26] reported a strong correlation between home and supervised clinical spirometry for both FEV1 and FVC (r = 0.97, p < 0.001) in a cohort of 93 participants, including COPD (n = 18), asthma (n = 22), bronchiectasis (n = 17), ILD (n = 17), and healthy controls (n = 19). They also showed that home spirometry slightly underestimated FEV1 (−0.10 L) and FVC (−0.03 L), with both values falling within narrow LoA [26]. Similarly, a U.S. RCT of beclomethasone dipropionate that included 713 patients with persistent asthma for 6-week exhibited a strong correlation between clinic-based and daily home spirometry FEV1 measurements (r > 0.8), with minimal outliers across all treatment groups [27]. The INMARK trial similarly reported consistent correlations (r = 0.72–0.84) between home and clinic FVC over 52 weeks, despite greater variability in home measurements [16]. These findings, replicated across COPD [28], asthma [28], and ILD cohorts [28–30], support the feasibility of home spirometry for lung function monitoring. However, widespread adoption depends on addressing the key barriers, including patient training, adherence to protocols, and device calibration. Standardized guidelines and large-scale studies are required to ensure data comparability and clinical integration.

In addition to technical limitations, the declining adherence to home spirometry over time remains a significant challenge. In the INMARK trial, which included 346 patients with IPF treated with nintedanib, mean weekly adherence to the home spirometry gradually declined over time, but consistently remained above 75% in each 4-week period over 52 weeks [27]. Similarly, in a study involving 43 patients with systemic sclerosis-associated ILD, adherence decreased over a 12-month follow-up; however, the median adherence remained high at 85% [31]. These findings indicate that, with proper guidance and support, home spirometry can be a feasible tool for real-time pulmonary function monitoring in clinical practice. Recent advancements in home spirometry technology have incorporated app-based features such as automated reminders for scheduled tests to improve adherence and ensure consistent data collection [28,32].

Despite some limitations, home spirometry has demonstrated reliability across various respiratory conditions, with results comparable to those of clinical measurements. The integration of supportive digital tools may further enhance their clinical utility and facilitate their broader adoption in both research and routine practice.

Wearable monitoring devices are increasingly recognized as valuable tools in respiratory medicine, providing continuous, real-time assessments of key physiological parameters [33]. These devices measure peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2), respiratory rate, heart rate, and physical activity levels, facilitating the comprehensive monitoring of patients with chronic respiratory diseases. Compared with traditional assessments that rely on periodic clinic visits, wearable devices enable longitudinal monitoring, offering deeper insights into disease progression and treatment efficacy [33,34].

Currently, various wearable devices are used in clinical and home settings [35]. Pulse oximeters, which are often worn on the wrist or fingers, are widely used to monitor oxygen saturation and detect hypoxemia [36,37]. In patients with COPD (n = 20), a 7-day continuous SpO2 monitoring with wearable finger pulse oximeters identified significant fluctuations in oxygen levels both within and between daytime and nighttime periods, emphasizing the importance of continuous monitoring for accurately assessing nocturnal desaturation and daily oxygen [38]. Respiratory bands and chest straps, which measure chest wall movements and respiratory rates, are useful for sleep apnea and pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) [39]. Multifunctional wearables such as Hexoskin (Carré Technologies Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada) or BioHarness (Zephyr Technology, Annapolis, MD, USA) collect data on respiration, heart rate, activity, and sleep, offering a comprehensive view of health [40,41]. Smart textiles with embedded sensors also allow long-term, noninvasive respiratory monitoring and expand clinical applications [42].

Recent advancements in smartwatch technology have brought respiratory health monitoring to the forefront. Devices such as the Apple Watch Series 6 (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) incorporate SpO2 tracking, respiratory rate monitoring, and irregular heart rhythm detection, and offer a convenient and widely accessible tool for continuous physiological assessment [43,44]. Their ease of use, wide availability, and integration with smartphone applications allow for real-time data sharing with healthcare providers.

Several studies have evaluated the accuracy and reliability of smartwatch-based respiratory-monitoring methods. Pipek et al. [45] demonstrated strong positive correlations between the Apple Watch Series 6 and commercial oximeters for heart rate (r = 0.995, p < 0.001) and SpO2 measurements (r = 0.81, p < 0.001) in patients with COPD (n = 23), ILD (n = 61), and healthy adults (n = 16), with no significant impact of skin color, wrist circumference, wrist hair, or enamel nails on measurement accuracy (p > 0.05). Similarly, a prospective study including patients with acute exacerbation of COPD (n = 167) reported a strong correlation in SpO2 between the Apple Watch Series 6 and medical-grade pulse oximetry (r = 0.89, intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.940), with a mean error of 0.458%, compared with arterial blood gas analysis. However, patients with tachypnea require multiple attempts to obtain accurate readings [46]. Another COPD study (n = 10) found that the device was user-friendly, but less reliable during respiratory distress [47,48]. These findings support the potential of smartwatches for accessible respiratory monitoring, although motion artifacts and sensor displacement may reduce the accuracy during daily activities or sleep. Further improvements in sensor stability and signal processing are required.

In addition to accuracy, wearable technology has been investigated for its role in disease management and patient engagement in chronic lung diseases. A meta-analysis of 37 studies on wearable technology in COPD revealed significant increases in daily step counts (mean difference [MD] 850 steps/day, 95% confidence interval [CI] 494–1,205) and six-minute walk distance (MD 5.81 m, 95% CI 1.02–10.61), particularly when combined with health coaching or PR [49]. However, these benefits are short-lived, with limited impact on the quality of life (QoL) and inconsistent effectiveness in managing exacerbations [49].

Digital health tools that combine wearables with mobile applications have shown potential for COPD management. Finney et al. [50] demonstrated the feasibility of using the MoreCare app (MoreCare, London, UK) on an Android tablet and the Garmin Vivofit 2 (Garmin Ltd., Olathe, KS, USA) in patients with COPD (n = 25), finding a moderate correlation between daily active minutes and FEV1 % predicted (ρ = 0.62, p = 0.005) and identifying multiple predictors of exacerbations, including sputum color and step count. A qualitative study (n = 14) further suggested that wearables and self-management applications could support real-time monitoring and early exacerbation detection, although usability, cost, data accuracy, and patient control remain key considerations [51].

Although wearable devices have demonstrated significant potential, some challenges remain unresolved. Usability during respiratory distress, variability in measurement accuracy, affordability, and patient adherence remain key barriers to widespread adoption [52,53]. Managing large volumes of biometric data requires secure storage and clear ownership policies. Compliance with regulations such as the HIPAA (in the U.S.) and GDPR (in the EU) is essential for protecting privacy and enabling responsible data sharing. Large-scale real-world studies are needed to validate the effectiveness and support for integration into routine care.

Smart inhalers with digital sensors offer significant advances in managing asthma and COPD by enabling real-time monitoring of inhaler use, adherence, and techniques [54]. The features include dose counters, audiovisual reminders, app connectivity, and feedback systems to optimize use. They support data-driven personalized treatment decisions [54,55].

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of smart inhalers for the management of airway diseases. In an RCT of 77 children with poorly controlled asthma, smart inhalers with electronic adherence monitoring and feedback significantly improved adherence (70% [smart inhaler] vs. 49% [control], p < 0.001) and were associated with reduced oral steroid use (p = 0.008) and hospital admissions (p < 0.001) [56]. Similarly, a 6-month cluster RCT of adults with moderate- to-severe asthma found that inhaler reminders significantly improved adherence (73% vs. 46%, p < 0.0001) and reduced severe exacerbations (11% vs. 28%, p = 0.013) [57]. The CONNECT-2 trial, a 24-week RCT including 391 patients with asthma, demonstrated that smart inhalers improved asthma control compared to standard care, with a 35% greater likelihood of achieving well-controlled asthma [58]. The study also reported increased clinician-patient interactions focused on inhaler technique, high adherence rates (79.2% at 1-month, 68.6% at 6-month), and a 38.2% reduction in reliever inhaler use [58]. These findings underscore the potential of smart inhalers to provide clinically actionable data, including medication usage patterns and inhalation techniques, thereby enabling clinicians to optimize treatment plans and improve therapeutic outcomes.

Despite their potential, challenges remain for the wide-spread adoption of smart inhalers. High cost, data privacy concerns, and the need for patient training in device use are significant barriers [59,60]. A qualitative study involving 24 stakeholders identified the key factors for successful implementation: clinical effectiveness, user-friendly design, integration with workflows, reimbursement policies, and data security [59]. While RCTs have shown improved short-term adherence and symptom control, evidence of long-term cost-effectiveness is limited. Future studies should assess the real-world cost benefits, including device costs, maintenance, and reimbursement models.

Telemedicine platforms enable real-time communication between patients and providers, thereby supporting remote healthcare delivery [61]. In chronic respiratory diseases, they facilitate continuous monitoring, timely interventions, and improved patient-provider communication, contributing to better disease management [62–64].

Several telemedicine platforms have been developed to support the management of respiratory diseases. Web-based tools, such as Doxyme (Doxyme LLC, Rochester, NY, USA) and Zoom for Healthcare (Zoom Video Communications, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), along with mobile health applications, including AsthmaMD (AsthmaMD Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA) and MyCOPD (My Health Ltd., Bournemouth, UK), provide functionalities for real-time symptom monitoring, treatment adjustments, medication reminders, and direct communication with healthcare providers. Virtual PR has shown comparable effectiveness to in-person programs, improving lung function and QoL while reducing access barriers [65,66].

However, several challenges remain, including limited digital literacy, disparities in internet access, data security concerns, and inherent limitations of virtual assessments in complex clinical cases [67]. Addressing these challenges is crucial for maximizing the effectiveness of telemedicine platforms. As these technologies continue to evolve, they are expected to play an increasingly integral role in respiratory care by enhancing accessibility, continuity of care, and patient outcomes across diverse populations.

Telemedicine has emerged as a pivotal tool in the management of chronic lung disease, allowing remote monitoring, early detection of disease progression, and timely therapeutic interventions. In COPD, ILD, asthma, and bronchiectasis, telemedicine facilitates objective symptom tracking, medication adherence monitoring, and virtual consultations, thereby enhancing patient engagement and optimizing clinical decision-making (Table 3). By integrating digital health technologies, telemedicine offers a structured approach to disease management, improving accessibility to care while supporting evidence-based personalized treatment strategies.

Telemedicine is increasingly being used in the management of COPD, offering innovative approaches that extend beyond traditional care. Several studies have shown that telemedicine interventions, including telemonitoring and telerehabilitation, can significantly improve patient outcomes. A meta-analysis of seven COPD studies found that telemedicine interventions significantly reduced COPD-related hospitalization rates (odds ratio [OR] 0.74, 95% CI 0.60–0.92) and mortality (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54–0.93) compared with usual care [68]. However, no significant improvements were observed in other outcomes, including acute exacerbation rates, dyspnea severity, and QoL [68]. Similarly, another RCT demonstrated that the telemonitoring group (n = 53) had a lower risk of first COPD-related readmission and fewer all-cause readmissions and emergency room visits than the usual care group (n = 53) [69]. Another RCT, including 281 patients with severe COPD (86% classified as Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage 3 or 4), also reported that telemonitoring was associated with a significant improvement in health-related QoL questionnaire scores after 6 months [70]. Despite these promising results, some studies have failed to identify significant benefits [71], highlighting the variability in the efficacy of telemedicine.

Home-based tele-rehabilitation programs have demonstrated efficacy comparable to traditional in-clinic rehabilitation programs for COPD. An 8-week home-based tele-rehabilitation program not only reduced dyspnea symptoms but also improved the six-minute walk distance, diaphragmatic mobility during deep breathing, and psychological well-being in patients with severe stable COPD (n = 174) [66]. In addition, an unblinded RCT involving patients with COPD and heart failure (n = 112) found that tele-rehabilitation improved exercise capacity and QoL while reducing dyspnea and disability over 4 months [72].

While telemedicine has shown promise in reducing hospitalizations and mortality, and enhancing QoL and exercise capacity in selected cases [66,68–70,72], variability in outcomes underscores the need for further research. The standardization of telemedicine protocols, improvements in digital literacy, and cost-effectiveness analyses are essential for fully integrating telemedicine into routine COPD care.

Telemedicine has emerged as a valuable tool in asthma management, addressing challenges such as poor adherence to inhaled corticosteroids, inadequate symptom monitoring, and the need for inhaler technique education [73]. A systematic review of 33 studies highlighted the potential of tailored digital interventions [74].

Both asynchronous and synchronous telemedicine approaches have been used to enhance asthma care. Asynchronous tools, including SMS reminders and web-based platforms, have been widely implemented to improve medication adherence, with studies demonstrating increase in inhaled corticosteroid use and reduced symptom burden in patients receiving telemedicine-based interventions [74] . Meanwhile, synchronous methods, such as video consultations, have been shown to facilitate real-time treatment adjustments and patient education, leading to better asthma control [73,74] . A meta-analysis of 22 studies further supported these findings, reporting that tele-case management significantly improved asthma control compared with usual care (standardized MD 0.78, 95% CI 0.56–1.01) [75].

Despite these benefits, the impact of telemedicine on reducing healthcare costs remains uncertain as studies have reported mixed results regarding hospitalization and emergency department visits among patients with asthma [76]. Barriers to its widespread implementation include technological limitations, digital access disparities, and variability in patient engagement. To optimize telemedicine-based asthma management, future models should integrate personalized features, such as interactive inhaler training, real-time symptom alerts, and environmental trigger monitoring, to enhance treatment adherence and disease control.

ILD encompasses a diverse group of chronic respiratory diseases characterized by lung parenchymal inflammation and fibrosis that require continuous monitoring and tailored rehabilitation strategies. With the growing integration of telemedicine, recent studies have examined its potential to enhance ILD care by improving access to monitoring tools, reducing healthcare burden, and supporting PR.

One promising application is telemonitoring, which enables continuous assessment of disease progression. Gillett et al. demonstrated that a 3-month telemonitoring program incorporating home spirometry and portable oximetry was well-received by patients with ILD (n = 60), with 89% recognizing its importance in clinical care, 90% accepting remote spirometry, and 98% approving pulse oximetry use [77]. Furthermore, a global survey of 207 clinicians revealed that 39% had already used telemedicine to monitor patients with ILD, and 78% of them found it quite effective or very effective [64]. The most common applications included identifying disease progression (70%), monitoring QoL (63%), tracking medication and oxygen use (63%), and reducing unnecessary in-person visits (63%) [64]. Clinicians identified smartphone applications, wearable sensors, and home spirometry with data transmission as the most useful telemonitoring tools, with symptoms (93%), oxygen saturation (74%), and physical activity (72%) as the most commonly tracked parameters [64].

In addition to monitoring, telemedicine is increasingly applied in PR. A 12-week telemonitoring-enabled home PR for patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis (n = 15), a rare ILD, demonstrated high adherence (≥ 87%), safety, and feasibility [78]. Participants with LAM experienced significant improvements in 6-minute walk distance (+36 ± 34 m, p = 0.003), cardiopulmonary exercise test duration (p = 0.04), muscular endurance (p = 0.008), QoL (p = 0.009–0.03), and fatigue (p = 0.001–0.03), while safely self-adjusting exercise intensity and oxygen use without adverse events [78]. Similarly, an eight-week virtual home-based PR program for patients with ILD (n = 14) found that both video-conference-led and self-directed interventions were feasible, safe, and well-accepted; however, the self-directed group experienced a higher dropout rate, emphasizing the need for structured support in remote exercise programs [79].

Despite these promising findings, significant barriers remain to the wider implementation of telemedicine in ILD care. The challenges in telemonitoring include technical difficulties with spirometry, communication of results, and data interpretation. A global clinician survey identified technical issues (47%), lack of training (45%), and organizational constraints (43%) as major obstacles to telemedicine adoption [64]. In addition, patient-related barriers, including lack of awareness (60%) and limited smartphone proficiency (49%), also hinder telemedicine adoption [64]. Furthermore, a survey of patients with ILD during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that while 78% were satisfied with telemedicine-based care, 37% faced challenges related to missed respiratory assessments, limited access to PR, and dissatisfaction with telephone-based consultations, indicating the need for more comprehensive telemedicine strategies [80].

To address these limitations, recent studies have explored alternative models of PR tailored to patients with ILD. A systematic review of telemedicine-driven PR in post-COVID-19 patients demonstrated encouraging results, suggesting its potential application in ILD management [81]. Recognizing the need for disease-specific programs, a telemedicine-based PR model was developed using an experience-based co-design, incorporating inputs from patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals to enhance desaturation safety, facilitate peer support, and adapt ILD-focused education, including palliative care guidance [82]. In support of the feasibility of telemedicine-based PR, an RCT is currently assessing its impact on functional capacity, QoL, and psychological well-being, positioning it as a cost-effective and accessible alternative to center-based PR [83]. A 4-week unsupervised telemedicine-based PR program further demonstrated significant short-term benefits, with improvements in functional capacity (6-minute walk distance: +14.2 m, p ≤ 0.001) and QoL (St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire score: +3.75, p ≤ 0.001), reinforcing its viability as a substitute for traditional center-based PR [84].

Although telemedicine offers a significant potential for ILD management, its long-term implementation requires addressing technical barriers, enhancing clinician and patient training, and integrating structured support systems. However, evidence regarding the effectiveness of telemedicine in ILD remains limited and mixed, highlighting the need for further research to evaluate its impact on various clinical and patient-centered outcomes [85]. Recent RCTs have provided robust evidence in this field. For example, an 8-week home-based telerehabilitation-assisted inspiratory muscle training program led to significant improvements in inspiratory muscle strength, exercise capacity, and dyspnea in patients with IPF [86]. In another RCT, a nurse and social worker-led palliative telecare intervention significantly improved QoL and mental health outcomes in patients with ILD, COPD, and heart failure [87]. Conversely, a comprehensive eHealth home monitoring program for IPF did not yield significant improvements in overall health-related QOL but showed benefits in psychological well-being and individualized medication adjustment [88]. These findings suggest that, while telemedicine can positively impact specific aspects of care, further studies are needed to define optimal implementation strategies and identify patient populations that are most likely to benefit.

Bronchiectasis, which is characterized by permanent bronchial dilation, presents unique challenges in long-term management and requires continuous monitoring, timely intervention, and effective airway clearance strategies [89]. Telemedicine has introduced novel approaches for addressing these challenges by enhancing patient access to care, improving exacerbation management, and reducing healthcare costs [90,91].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the University of Connecticut Center for Bronchiectasis Care reported positive experiences with telemedicine-based visits, finding them effective in managing mild exacerbations, monitoring patients undergoing treatment for nontuberculous mycobacterial infections, and facilitating telerehabilitation to improve exercise capacity and QoL [92]. However, further research is needed to determine their impact on reducing exacerbations and overall healthcare costs [92]. Similarly, a qualitative study on telemedicine physiotherapy for patients with bronchiectasis (n = 13) revealed initial skepticism but overall acceptance, with reported benefits, including continued access to treatment and reduced infection risk [90]. However, limitations in physical assessments and patient preferences suggest that telemedicine should complement rather than replace in-person care [90]. A survey of patients with bronchiectasis and physiotherapists (n = 48) in the United Kingdom highlighted the underutilization of telemedicine in physiotherapy despite its perceived potential [93]. While 56% of physiotherapists had already integrated digital tools, a substantial proportion did not, although both physiotherapists and patients expressed strong interest in remote and digital methods for follow-up care, emphasizing the need for further research on implementation and acceptability [93].

However, despite its potential, the complete effect of telemedicine on bronchiectasis remains unclear. Although benefits, such as shorter appointment times, increased clinical review frequency, and cost savings, have been observed in cystic fibrosis-associated bronchiectasis [94], evidence supporting similar outcomes in bronchiectasis remains limited. Further studies are required to evaluate its effectiveness in reducing exacerbations and infections and optimizing healthcare utilization.

Lung transplantation is a life-saving intervention for patients with end-stage lung disease requiring long-term monitoring to ensure graft survival and patient well-being [95]. Telemedicine has emerged as a transformative tool in both pre- and post-transplant care, offering innovative solutions for improving patient outcomes and optimizing healthcare delivery [96]. A systematic review by Gholamzadeh et al. analyzed 27 studies, identifying telemonitoring (55.6%) as the most frequently used intervention, followed by teleconsultation (14.8%) and telerehabilitation (14.8%). These interventions primarily focused on early detection of allograft dysfunction, improving medication adherence, and minimizing the need for in-person clinic visits, highlighting the growing role of telemedicine in lung transplantation [97].

In the pre-transplantation phase, telemedicine has demonstrated effectiveness in improving patient monitoring, communication, and self-management, although its impact on clinical outcomes remains uncertain. DeVito Dabbs et al. [98] conducted an RCT with lung transplant recipients (n = 201), demonstrating that a mobile health intervention significantly increased self-monitoring (OR 5.11, 95% CI 2.95–8.87), adherence to medical regimens (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.01–2.66), and reporting of abnormal health indicators (OR 8.9, 95% CI 3.60–21.99) compared with usual care. However, there was no significant difference in rehospitalization or mortality, highlighting the need for further research on long-term clinical benefits. Mullan et al. [99] similarly evaluated an electronic diary-based telemonitoring system in 119 lung transplant candidates and found high adherence and improved communication with the transplant team, but no significant differences in hospital stay or survival at 4 months compared with standard telephone reporting. In addition, Wilkinson et al. [100] assessed telemedicine in 16 patients with cystic fibrosis awaiting lung transplantation and reported that while telemedicine did not significantly alter clinical outcomes, it improved body image perception and was highly valued for enhancing specialist support.

In the post-transplant phase, telemedicine plays a critical role in facilitating rigorous monitoring to detect complications, such as rejection, infection, and immunosuppressive therapy-related side effects. Studies have supported its feasibility as a scalable solution for remote patient management, particularly under healthcare-resource constraints. An RCT (n = 65) compared a computer-based Bayesian algorithm with manual nurse triage for lung transplant recipients using home spirometry [101]. After 1 year, there were no significant differences in FEV1 or QoL (SF-36) scores between the groups, although both approaches demonstrated efficacy in detecting changes in spirometry and symptoms [101]. These findings highlight the potential of automated triage systems to support remote monitoring while alleviating the clinical workload. Similarly, Sengpiel et al. [102] evaluated home spirometry using Bluetooth-enabled data transfer in an RCT (n = 56), reported high adherence (97.2%). While the intervention did not significantly reduce the time to physician consultation compared with standard home spirometry, patients in the Bluetooth group reported lower anxiety levels (mean 1.5 [intervention] vs. 4.0 [control], p = 0.04), suggesting potential psychological benefits [102]. In a broader cohort, Sidhu et al. [96] assessed telemedicine-based follow-up in lung transplant recipients (n = 204) residing outside major transplant centers and found no significant differences in mortality outcomes compared with in-person visits. However, telemedicine substantially reduces patient travel burden and financial costs, reinforcing its role in expanding access to specialized transplant care without compromising patient safety [96]. Furthermore, Geramita et al. [103] followed up on an RCT evaluating Pocket PATH, a mobile health intervention for lung transplant recipients (n = 105), and found that while it initially reduced nonadherence to lifestyle requirements (p < 0.05), its effects were not sustained beyond 3.9 years post-transplant. Younger age, acute rejection, anxiety, and prior nonadherence have been identified as key risk factors for long-term nonadherence, underscoring the need for strategies to sustain the benefits of digital health interventions [103].

Despite this promise, barriers to widespread telemedicine adoption for lung transplantation persist. Suhling et al. [104] reported that while 78.2% of solid organ transplant recipients owned smartphones, only 70.5% used the Internet daily, indicating barriers to telemedicine adoption. Moreover, Fadaizadeh et al. [105] found that 15% of lung transplant patients faced technical difficulties with home spirometry monitoring, underscoring the need for user-friendly platforms and robust technical support. Addressing these limitations is essential to maximize the impact of telemedicine on peri-transplant care, ensuring equitable access, sustained patient engagement, and long-term clinical benefits.

Despite the rapid expansion of telemedicine, several limitations hinder its integration into routine care. Regulatory inconsistencies, including fragmented licensure systems and unclear liabilities in cross-state care, remain substantial barriers [106,107]. Reimbursement frameworks, particularly for Medicaid and commercial insurance, are often restrictive and lack payment parity for in-person care [107]. Data security and privacy concerns are growing as telehealth platforms collect and transmit sensitive health information without standardized safeguards [108]. Interoperability challenges and the limited integration of patient-generated data into electronic health records further reduce clinical utility [106]. Usability issue such as complex interfaces, insufficient training, and device fragmentation, impede patient and provider engagement [109,110]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the absence of regulatory and infrastructure readiness in many countries has highlighted global disparities in telemedicine implementation and emphasized the need for formal integration into national health systems [11]. Although telehealth enabled remote triage and continuity of care in high-risk settings during this period [107], the sustainable integration of telemedicine requires coordinated investment in policy reform, system interoperability, and evidence-based implementation strategies that reflect patient needs and support long-term value, as highlighted in systematic reviews of patient satisfaction and outcome optimization [111].

The future of telemedicine in the management will depend on both short-term adaptation and long-term strategic development. In the short-term, efforts should focus on enhancing accessibility, usability, and immediate clinical integration. This includes the deployment of app-based platforms with interactive self-management tools, expansion of home-based rehabilitation programs, and integration of wearable devices for real-time monitoring of oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and lung function [112,113]. These tools can reduce the dependence on in-person visits and improve day-to-day disease management. Addressing current disparities, especially among older adults, rural populations, and those with limited digital literacy, will require targeted interventions such as multilingual interfaces, simplified user designs, and standardized telemedicine training for patients and providers [62,114].

Telemedicine is expected to evolve over the long term through AI-driven predictive models and machine learning algorithms that can anticipate exacerbations, optimize therapy, and personalize care pathways [115]. Comprehensive data integration from continuous monitoring platforms can support automated triage and remote decision-making. To support sustainable adoption, robust regulatory frameworks must be developed to standardize protocols, protect patient data, and streamline reimbursement [116]. Future large-scale RCTs should focus on evaluating the long-term clinical outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and patient-reported benefits to further solidify the role of telemedicine as an integral component of chronic lung disease management. Establishing evidence-based guidelines and refining implementation strategies are essential for maximizing the potential of telemedicine in respiratory care.

Telemedicine has demonstrated significant potential in the management of chronic lung diseases by offering improved access to care, early detection of disease progression, and enhanced patient self-management. Clinical evidence supports its role in reducing hospitalization, optimizing treatment adherence, and facilitating long-term disease monitoring. However, barriers such as disparities in digital literacy, limited access to reliable Internet, and the need for standardized regulatory frameworks remain challenges for widespread implementation. Future research should focus on implementing telemedicine in real-world clinical settings by integrating it with existing electronic health records, addressing reimbursement policies, and ensuring seamless clinician- patient communication through AI-driven automated triage systems.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Hee-Young Yoon: investigation, data curation, formal analysis, software, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, visualization; Jin Woo Song: conceptualization, methodology, resources, investigation, validation, writing - review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Basic Science Research Program (NRF-2022R1A2B5B02001602) and Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (NRF-2022M3A9E4082647) of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea. This study was supported by the National Institute of Health Research Project (2024ER090500) and the Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute through the Core Technology Development Project for Environmental Diseases Prevention and Management Program funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (RS-2022-KE002197), Republic of Korea.

Figure 1

Integration of digital health technologies in telemedicine for chronic lung disease management. This figure illustrates the key digital health technologies used in telemedicine. Home spirometry enables remote monitoring of lung function. Wearable devices can track physiological parameters. Smart inhalers improve medication adherence through real-time tracking. Telemedicine platforms integrate these tools for remote monitoring and patient-provider communication.

Table 1

Key technologies in telemedicine

Table 2

Comparison of home and clinic-based spirometry

Table 3

Clinical outcomes of telemedicine interventions in chronic lung diseases

REFERENCES

1. GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:585–596.

2. GBD 2019 Chronic Respiratory Diseases Collaborators. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: an update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. EClinicalMedicine 2023;59:101936.

3. Wong AW, Koo J, Ryerson CJ, Sadatsafavi M, Chen W. A systematic review on the economic burden of interstitial lung disease and the cost-effectiveness of current therapies. BMC Pulm Med 2022;22:148.

4. Chen S, Kuhn M, Prettner K, et al. The global economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for 204 countries and territories in 2020–50: a health-augmented macroeconomic modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2023;11:e1183–e1193.

5. Goodridge D, Hutchinson S, Wilson D, Ross C. Living in a rural area with advanced chronic respiratory illness: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:54–58.

6. Meghji J, Jayasooriya S, Khoo EM, Mulupi S, Mortimer K. Chronic respiratory disease in low-income and middle-income countries: from challenges to solutions. J Pan Afr Thorac Soc 2022;3:92–97.

7. Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1196–e1252.

8. Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health 2016;22:342–375.

9. Nittari G, Khuman R, Baldoni S, et al. Telemedicine practice: review of the current ethical and legal challenges. Telemed J E Health 2020;26:1427–1437.

10. Haleem A, Javaid M, Singh RP, Suman R. Telemedicine for healthcare: capabilities, features, barriers, and applications. Sens Int 2021;2:100117.

11. Ohannessian R, Duong TA, Odone A. Global telemedicine implementation and integration within health systems to fight the COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020;6:e18810.

12. Valentino LA, Skinner MW, Pipe SW. The role of telemedicine in the delivery of health care in the COVID-19 pandemic. Haemophilia 2020;26:e230–e231.

13. Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society technical statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;200:e70–e88.

14. Mathioudakis AG, Abroug F, Agusti A, et al.; DECODE-NET. ERS statement: a core outcome set for clinical trials evaluating the management of COPD exacerbations. Eur Respir J 2022;59:2102006.

15. Maher TM, Corte TJ, Fischer A, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with unclassifiable progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:147–157.

16. Noth I, Cottin V, Chaudhuri N, et al.; INMARK trial investigators. Home spirometry in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: data from the INMARK trial. Eur Respir J 2021;58:2001518.

17. Wijsenbeek MS, Bendstrup E, Valenzuela C, et al. Disease behaviour during the peri-diagnostic period in patients with suspected interstitial lung disease: the STARLINER study. Adv Ther 2021;38:4040–4056.

18. Lee LA, Bailes Z, Barnes N, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily single-inhaler triple therapy (FF/UMEC/VI) versus FF/VI in patients with inadequately controlled asthma (CAPTAIN): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3A trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:69–84.

19. Ostrom NK, Raphael G, Tillinghast J, Hickey L, Small CJ. Randomized trial to assess the efficacy and safety of beclomethasone dipropionate breath-actuated inhaler in patients with asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc 2018;39:117–126.

20. Spargo M, Ryan C, Downey D, Hughes C. Development of a core outcome set for trials investigating the long-term management of bronchiectasis. Chron Respir Dis 2019;16:1479972318804167.

21. Anand R, McLeese R, Busby J, et al. Unsupervised home spirometry versus supervised clinic spirometry for respiratory disease: a systematic methodology review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev 2023;32:220248.

22. Oppenheimer J, Hanania NA, Chaudhuri R, et al. Clinic vs home spirometry for monitoring lung function in patients with asthma. Chest 2023;164:1087–1096.

23. Oppelaar MC, van Helvoort HA, Bannier MA, et al. Accuracy, reproducibility, and responsiveness to treatment of home spirometry in cystic fibrosis: multicenter, retrospective, observational study. J Med Internet Res 2024;26:e60892.

24. Edmondson C, Westrupp N, Short C, et al. Unsupervised home spirometry is not equivalent to supervised clinic spirometry in children and young people with cystic fibrosis: results from the CLIMB-CF study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2023;58:2871–2880.

25. Paynter A, Khan U, Heltshe SL, Goss CH, Lechtzin N, Hamblett NM. A comparison of clinic and home spirometry as longtudinal outcomes in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2022;21:78–83.

26. Wilson CL, McLaughlin C, Cairncross A, et al. Home spirometry appears accurate and feasible for monitoring chronic respiratory disease. ERJ Open Res 2024;10:00937–2023.

27. Kerwin EM, Hickey L, Small CJ. Relationship between handheld and clinic-based spirometry measurements in asthma patients receiving beclomethasone. Respir Med 2019;151:35–42.

28. Exarchos KP, Gogali A, Sioutkou A, Chronis C, Peristeri S, Kostikas K. Validation of the portable Bluetooth® Air Next spirometer in patients with different respiratory diseases. Respir Res 2020;21:79.

29. Khan F, Howard L, Hearson G, et al. Clinical utility of home versus hospital spirometry in fibrotic interstitial lung disease: evaluation after INJUSTIS interim analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2022;19:506–509.

30. Ilić M, Javorac J, Milenković A, et al. Home-based spirometry in patients with interstitial lung diseases: a real-life pilot "FACT" study from Serbia. J Pers Med 2023;13:793.

31. Velauthapillai A, Moor CC, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Wijsenbeek- Lourens MS, van den Ende CHM, Vonk MC. Detection of decline in pulmonary function in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease using home monitoring in the Netherlands (DecreaSSc): a prospective, observational study. Lancet Rheumatol 2025;7:e178–e186.

32. Ramsey RR, Plevinsky JM, Guilbert TW, Carmody JK, Hommel KA. Technology-assisted stepped-care to promote adherence in adolescents with asthma: a pilot study. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2023;30:415–424.

33. Vitazkova D, Foltan E, Kosnacova H, et al. Advances in respiratory monitoring: a comprehensive review of wearable and remote technologies. Biosensors (Basel) 2024;14:90.

34. Dai N, Lei IM, Li Z, Li Y, Fang P, Zhong J. Recent advances in wearable electromechanical sensors—Moving towards machine learning-assisted wearable sensing systems. Nano Energy 2023;105:108041.

35. Iqbal SMA, Mahgoub I, Du E, Leavitt MA, Asghar W. Advances in healthcare wearable devices. npj Flex Electron 2021;5:9.

36. Santos M, Vollam S, Pimentel MA, et al. The use of wearable pulse oximeters in the prompt detection of hypoxemia and during movement: diagnostic accuracy study. J Med Internet Res 2022;24:e28890.

37. Lee HS, Noh B, Kong SU, et al. Fiber-based quantum-dot pulse oximetry for wearable health monitoring with high wavelength selectivity and photoplethysmogram sensitivity. Npj Flex Electron 2023;7:15.

38. Buekers J, Theunis J, De Boever P, et al. Wearable finger pulse oximetry for continuous oxygen saturation measurements during daily home routines of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) over one week: ob servational study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7:e12866.

39. De Fazio R, Greco MR, De Vittorio M, Visconti P. A differential inertial wearable device for breathing parameter detection: hardware and firmware development, experimental characterization. Sensors (Basel) 2022;22:9953.

40. Jayasekera S, Hensel E, Robinson R. Feasibility of using the Hexoskin Smart Garment for natural environment observation of respiration topography. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:7012.

41. Johnstone JA, Ford PA, Hughes G, Watson T, Mitchell AC, Garrett AT. Field based reliability and validity of the bioharness ™ multivariable monitoring device. J Sports Sci Med 2012;11:643–652.

42. Roudjane M, Bellemare-Rousseau S, Drouin E, et al. Smart T-shirt based on wireless communication spiral fiber sensor array for real-time breath monitoring: validation of the technology. IEEE Sens J 2020;20:10841–10850.

43. Spaccarotella C, Polimeni A, Mancuso C, Pelaia G, Esposito G, Indolfi C. Assessment of non-invasive measurements of oxygen saturation and heart rate with an apple smartwatch: comparison with a standard pulse oximeter. J Clin Med 2022;11:1467.

44. Windisch P, Schröder C, Förster R, Cihoric N, Zwahlen DR. Accuracy of the Apple Watch oxygen saturation measurement in adults: a systematic review. Cureus 2023;15:e35355.

45. Pipek LZ, Nascimento RFV, Acencio MMP, Teixeira LR. Comparison of SpO2 and heart rate values on Apple Watch and conventional commercial oximeters devices in patients with lung disease. Sci Rep 2021;11:18901.

46. Arslan B, Sener K, Guven R, et al. Accuracy of the Apple Watch in measuring oxygen saturation: comparison with pulse oximetry and ABG. Ir J Med Sci 2024;193:477–483.

47. Arnaert A, Sumbly P, da Costa D, Liu Y, Debe Z, Charbonneau S. Acceptance of the Apple Watch Series 6 for telemonitoring of older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: qualitative descriptive study part 1. JMIR Aging 2023;6:e41549.

48. Liu Y, Arnaert A, da Costa D, Sumbly P, Debe Z, Charbonneau S. Experiences of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using the Apple Watch Series 6 versus the traditional finger pulse oximeter for home SpO2 self-monitoring: qualitative study part 2. JMIR Aging 2023;6:e41539.

49. Shah AJ, Althobiani MA, Saigal A, Ogbonnaya CE, Hurst JR, Mandal S. Wearable technology interventions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit Med 2023;6:222.

50. Finney LJ, Avey S, Wiseman D, et al. Using an electronic diary and wristband accelerometer to detect exacerbations and activity levels in COPD: a feasibility study. ERJ Open Res 2023;9:00366–2023.

51. Wu RC, Ginsburg S, Son T, Gershon AS. Using wearables and self-management apps in patients with COPD: a qualitative study. ERJ Open Res 2019;5:00036–2019.

52. Canali S, Schiaffonati V, Aliverti A. Challenges and recommendations for wearable devices in digital health: data quality, interoperability, health equity, fairness. PLOS Digit Health 2022;1:e0000104.

53. Jafleh EA, Alnaqbi FA, Almaeeni HA, Faqeeh S, Alzaabi MA, Al Zaman K. The role of wearable devices in chronic disease monitoring and patient care: a comprehensive review. Cureus 2024;16:e68921.

54. Chan AHY, Pleasants RA, Dhand R, et al. Digital inhalers for asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a scientific perspective. Pulm Ther 2021;7:345–376.

55. Zabczyk C, Blakey JD. The effect of connected "smart" inhalers on medication adherence. Front Med Technol 2021;3:657321.

56. Morton RW, Elphick HE, Rigby AS, et al. STAAR: a randomised controlled trial of electronic adherence monitoring with reminder alarms and feedback to improve clinical outcomes for children with asthma. Thorax 2017;72:347–354.

57. Foster JM, Usherwood T, Smith L, et al. Inhaler reminders improve adherence with controller treatment in primary care patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;134:1260–1268e3.

58. Mosnaim GS, Hoyte FCL, Safioti G, et al. Effectiveness of a maintenance and reliever Digihaler System in asthma: 24-week randomized study (CONNECT2). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2024;12:385–395e4.

59. van de Hei SJ, Stoker N, Flokstra-de Blok BMJ, et al. Anticipated barriers and facilitators for implementing smart inhalers in asthma medication adherence management. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2023;33:22.

60. Pleasants RA, Chan AH, Mosnaim G, et al. Integrating digital inhalers into clinical care of patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2022;205:107038.

61. Goharinejad S, Hajesmaeel-Gohari S, Jannati N, Goharinejad S, Bahaadinbeigy K. Review of systematic reviews in the field of telemedicine. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2021;35:184.

62. Ambrosino N, Vagheggini G, Mazzoleni S, Vitacca M. Tele medicine in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Breathe (Sheff) 2016;12:350–356.

63. Persaud YK. Using telemedicine to care for the asthma patient. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2022;22:43–52.

64. Althobiani M, Alqahtani JS, Hurst JR, Russell AM, Porter J. Telehealth for patients with interstitial lung diseases (ILD): results of an international survey of clinicians. BMJ Open Respir Res 2021;8:e001088.

65. Knox L, Dunning M, Davies CA, et al. Safety, feasibility, and effectiveness of virtual pulmonary rehabilitation in the real world. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2019;14:775–780.

66. Zhang L, Maitinuer A, Lian Z, et al. Home based pulmonary tele-rehabilitation under telemedicine system for COPD: a cohort study. BMC Pulm Med 2022;22:284.

68. Koh JH, Chong LCY, Koh GCH, Tyagi S. Telemedical interventions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management: umbrella review. J Med Internet Res 2023;25:e33185.

69. Ho TW, Huang CT, Chiu HC, et al.; HINT Study Group. Effectiveness of telemonitoring in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in taiwan-a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 2016;6:23797.

70. Tupper OD, Gregersen TL, Ringbaek T, et al. Effect of telehealth care on quality of life in patients with severe COPD: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018;29. 13:2657–2662.

71. Li X, Xie Y, Zhao H, Zhang H, Yu X, Li J. Telemonitoring interventions in COPD patients: overview of systematic reviews. Biomed Res Int 2020;2020:5040521.

72. Bernocchi P, Vitacca M, La Rovere MT, et al. Home-based telerehabilitation in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2018;47:82–88.

73. Bocian IY, Chin AR, Rodriguez A, Collins W, Sindher SB, Chinthrajah RS. Asthma management in the digital age. Front Allergy 2024;5:1451768.

74. Almasi S, Shahbodaghi A, Asadi F. Efficacy of telemedicine for the management of asthma: a systematic review. Tanaffos 2022;21:132–145.

75. Chongmelaxme B, Lee S, Dhippayom T, Saokaew S, Chaiyakunapruk N, Dilokthornsakul P. The effects of telemedicine on asthma control and patients' quality of life in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:199–216e11.

76. Jung Y, Kim J, Park DA. Effectiveness of telemonitoring intervention in children and adolescents with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Korean Acad Nurs 2018;48:389–406.

77. Gillett G, Shah RJ, DeDent AM, Farrand E. Remote patient monitoring for managing interstitial lung disease: a mixed-methods process evaluation. Chest Pulm 2025;3:1100122.

78. Child CE, Kelly ML, Sizelove H, et al. A remote monitoring-enabled home exercise prescription for patients with interstitial lung disease at risk for exercise-induced desaturation. Respir Med 2023;218:107397.

79. Sarmento A, King K, Sanchez-Ramirez DC. Using remote technology to engage patients with interstitial lung diseases in a home exercise program: a pilot study. Life (Basel) 2024;14:265.

80. Tikellis G, Corte T, Glaspole IN, et al. Understanding the telehealth experience of care by people with ILD during the COVID-19 pandemic: what have we learnt? BMC Pulm Med 2023;23:113.

81. Pescaru CC, Crisan AF, Marc M, et al. A systematic review of telemedicine-driven pulmonary rehabilitation after the acute phase of COVID-19. J Clin Med 2023;12:4854.

82. Brighton LJ, Spain N, Gonzalez-Nieto J, et al. Remote pulmonary rehabilitation for interstitial lung disease: developing the model using experience-based codesign. BMJ Open Respir Res 2024;11:e002061.

83. Amin R, Maiya GA, Mohapatra AK, et al. Effect of a homebased pulmonary rehabilitation program on functional capacity and health-related quality of life in people with interstitial lung disease - a randomized controlled trial protocol. Respir Med 2022;201:106927.

84. Amin R, Vaishali K, Maiya GA, Mohapatra AK, Acharya V, Lakshmi RV. Influence of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation program among people with interstitial lung disease: a pre-post study. Physiother Theory Pract 2024;40:2265–2273.

85. Holland AE, Glaspole I. Lockdown as the mother of invention: disruptive technology in a disrupted time. Lancet Respir Med 2023;11:9–11.

86. Aktan R, Tertemiz KC, Yiğit S, Özalevli S, Ozgen Alpaydin A, Uçan ES. Effects of home-based telerehabilitation-assisted inspiratory muscle training in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a randomized controlled trial. Respirology 2024;29:1077–1084.

87. Bekelman DB, Feser W, Morgan B, et al. Nurse and social worker palliative telecare team and quality of life in patients with COPD, heart failure, or interstitial lung disease: the ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2024;331:212–223.

88. Moor CC, Mostard RLM, Grutters JC, et al. Home monitoring in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;202:393–401.

89. Chalmers JD, Sethi S. Raising awareness of bronchiectasis in primary care: overview of diagnosis and management strategies in adults. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2017;27:18.

90. Lee AL, Tilley L, Baenziger S, Hoy R, Glaspole I. The perceptions of telehealth physiotherapy for people with bronchiectasis during a global pandemic-a qualitative study. J Clin Med 2022;11:1315.

91. Shah NM, Kaltsakas G. Telemedicine in the management of patients with chronic respiratory failure. Breathe (Sheff) 2021;17:210008.

92. Congrete S, Metersky ML. Telemedicine and remote monitoring as an adjunct to medical management of bronchiectasis. Life (Basel) 2021;11:1196.

93. O'Neill K, O'Neill B, McLeese RH, et al. Digital technologies in bronchiectasis physiotherapy services: a survey of patients and physiotherapists in a UK centre. ERJ Open Res 2024;10:00013–2024.

94. Conway S, Balfour-Lynn IM, De Rijcke K, et al. European cystic fibrosis society standards of care: framework for the cystic fibrosis centre. J Cyst Fibros 2014;13:Suppl 1. S3–S22.

95. Bos S, Vos R, Van Raemdonck DE, Verleden GM. Survival in adult lung transplantation: where are we in 2020? Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2020;25:268–273.

96. Sidhu A, Chaparro C, Chow CW, Davies M, Singer LG. Outcomes of telehealth care for lung transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 2019;33:e13580.

97. Gholamzadeh M, Abtahi H, Safdari R. Telemedicine in lung transplant to improve patient-centered care: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform 2022;167:104861.

98. DeVito Dabbs A, Song MK, Myers BA, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a mobile health intervention to promote self-management after lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 2016;16:2172–2180.

99. Mullan B, Snyder M, Lindgren B, Finkelstein SM, Hertz MI. Home monitoring for lung transplant candidates. Prog Transplant 2003;13:176–182.

100. Wilkinson OM, Duncan-Skingle F, Pryor JA, Hodson ME. A feasibility study of home telemedicine for patients with cystic fibrosis awaiting transplantation. J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:182–185.

101. Finkelstein SM, Lindgren BR, Robiner W, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing health and quality of life of lung transplant recipients following nurse and computer-based triage utilizing home spirometry monitoring. Telemed J E Health 2013;19:897–903.

102. Sengpiel J, Fuehner T, Kugler C, et al. Use of telehealth technology for home spirometry after lung transplantation: a randomized controlled trial. Prog Transplant 2010;20:310–317.

103. Geramita EM, DeVito Dabbs AJ, DiMartini AF, et al. Impact of a mobile health intervention on long-term nonadherence after lung transplantation: follow-up after a randomized controlled trial. Transplantation 2020;104:640–651.

104. Suhling H, Rademacher J, Zinowsky I, et al. Conventional vs. tablet computer-based patient education following lung transplantation--a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e90828.

105. Fadaizadeh L, Najafizadeh K, Shajareh E, Shafaghi S, Hosseini M, Heydari G. Home spirometry: assessment of patient compliance and satisfaction and its impact on early diagnosis of pulmonary symptoms in post-lung transplantation patients. J Telemed Telecare 2016;22:127–131.

107. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1679–1681.

108. MacKinnon GE, Brittain EL. Mobile health technologies in cardiopulmonary disease. Chest 2020;157:654–664.

109. Siegel A, Zuo Y, Moghaddamcharkari N, McIntyre RS, Rosenblat JD. Barriers, benefits and interventions for improving the delivery of telemental health services during the corona-virus disease 2019 pandemic: a systematic review. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2021;34:434–443.

110. Carayon P, Hoonakker P. Human factors and usability for health information technology: old and new challenges. Yearb Med Inform 2019;28:71–77.

111. Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, Tran L, Vela J, Brooks M. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016242.

112. Xian X. Frontiers of wearable biosensors for human health monitoring. Biosensors (Basel) 2023;13:964.

113. Chung C, Lee JW, Lee SW, Jo MW. Clinical efficacy of mobile app-based, self-directed pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024;12:e41753.

114. Phillips Z, Wong L, Crotty K, et al. Implementing an experiential telehealth training and needs assessment for residents and faculty at a veterans affairs primary care clinic. J Grad Med Educ 2023;15:456–462.

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 276 View

- 88 Download

- Related articles

-

Telemedicine in Korea: bridging the gap between convenience and clinical safety2026 January;41(1)

Sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease: from bench to bedside2023 May;38(3)

Update on heart failure management and future directions2019 July;34(4)

Update on heart failure management and future directions2019 January;34(1)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print