|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 40(2); 2025 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background/Aims

Tracheostomy is a crucial intervention for severe pneumonia patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation (MV). However, debate persists regarding the influence of tracheostomy timing and performance on long-term survival outcomes. This study utilized propensity score matching to assess the impact of tracheostomy timing and performance on patient survival outcomes.

Methods

A retrospective observational study employing propensity score matching was conducted of respiratory intensive care unit (ICU) patients who underwent prolonged acute MV due to severe pneumonia from 2008 to 2023. The primary outcome was the 90-day cumulative mortality rate, with secondary outcomes including ICU medical resource utilization rates.

Results

Out of 1,078 patients, 545 underwent tracheostomy with a median timing of 7 days. The tracheostomy group exhibited lower 90-day cumulative mortality and a higher survival probability (hazard ratio [HR] 0.52, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.43ŌĆō0.63) than the no-tracheostomy group. The tracheostomy group had higher ICU medical resource utilization rates and medical expenditures. The early tracheostomy group (Ōēż 7 days) had lower ICU medical resource utilization rates and medical expenditures than the late tracheostomy group (> 7 days). However, there were no significant differences in the 90-day cumulative mortality rate and survival probability based on tracheostomy timing (HR 0.94, 95% CI 0.70ŌĆō1.28).

Conclusions

Tracheostomy in patients with severe pneumonia requiring prolonged MV significantly reduced the 90-day mortality rate, and early tracheostomy may offer additional benefits for resource utilization efficiency. These findings underscore the importance of considering tracheostomy timing in optimizing patient outcomes and healthcare resource allocation.

The rising incidence of severe pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation (MV) in intensive care units (ICUs) often requires long-term ventilator care and substantial utilization of medical resources [1ŌĆō3]. However, sustaining long-term ventilator care through extended translaryngeal intubation poses risks of laryngeal and tracheal damage and elevates the likelihood of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) [4]. Tracheostomy is a useful option for patients requiring prolonged MV, offering benefits such as decreased airway dead space and resistance, improved patient comfort, reduced sedative usage, and a lower incidence of nosocomial pneumonia [5,6].

Although numerous studies have demonstrated the favorable impact of tracheostomy on hospital outcomes for patients requiring prolonged MV, its effects on long-term outcomes remain controversial [7ŌĆō9]. Additionally, the criteria for determining the timing of tracheostomy, whether early or late, and its subsequent influence on survival outcomes remain subjects of ongoing debate [5,10,11]. These controversies may be due to significant heterogeneity related to the specific diseases studied, the timing of tracheostomy, characteristics of the ICU setting, and the extent of medical resource utilization.

In Korea, severe pneumonia is one of the most common conditions among critically ill patients and imposes a significant burden on medical resources [12]. Despite this, research on the effect of tracheostomy on patient outcomes remains limited. We hypothesize that the timing and performance of tracheostomy in patients with severe pneumonia requiring prolonged MV will influence both patient outcomes and medical resource utilization. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the impact of tracheostomy on survival outcomes and medical resource utilization in patients requiring MV due to severe pneumonia, using propensity score matching (PSM) to overcome the inherent limitations of retrospective studies.

This study was conducted in the 12-bed adult respiratory ICU of a 1,200-bed university-affiliated tertiary care hospital in Busan, Korea. The ICU maintained a nurse-to-bed ratio of 1:3 and was equipped with a hemodynamic monitoring system for each patient. Standard care guidelines for critically ill patients were followed [13].

This retrospective observational cohort study screened all consecutive patients requiring MV treatment in the respiratory ICU from March 1, 2008 to May 31, 2023. Inclusion criteria were patients diagnosed with acute respiratory failure due to community-acquired or hospital-acquired pneumonia [14,15], who also received MV for more than 96 hours (defined as prolonged acute MV, PAMV) [16]. Exclusion criteria included patients requiring MV for conditions other than pneumonia, those who had previously undergone tracheostomies, individuals with pre-existing directives that limited life-sustaining treatments, and individuals under the age of 18. For patients with multiple ICU admissions, data from only their first ICU admission were collected.

The primary outcome was the 90-day cumulative mortality rate. This included all cases of death that occurred within 90 days from the start of MV. Secondary outcomes included discharge outcomes, total medical expenditures during the hospital stay, and medical resource utilization rates in the ICU. Discharge outcomes were assessed based on the discharge destination (e.g., death, home, or step-down hospital) and decannulation rates before hospital discharge. Total medical expenditures were calculated as the cost of all medical resources used during the patientŌĆÖs hospital stay. Health ratio indicators such as the bed occupancy rate (BOR), bed turnover rate (BTR), average length of stay (LOS), and turnover interval (TI) were used to evaluate the efficiency of medical resource utilization [17]. These indicators have been evaluated as factors impacting medical expenditures, playing an important role in understanding how effective management of medical resources contributes to reducing medical costs [18,19].

Demographic and clinical data, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), duration of MV, LOS in the ICU and hospital, and mortality in the ICU and hospital, were collected retrospectively from patientsŌĆÖ electronic medical records. The severity of illness was measured using the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, and accompanying organ failure was assessed according to the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [20,21]. The APACHE II and SOFA scores were calculated from laboratory and clinical data obtained in the first 24 hours of intubation. CharlsonŌĆÖs comorbidity index (CCI) was evaluated to determine concurrent comorbidities before ICU admission [22].

All tracheostomies were surgical and were determined by the attending physician and then referred to a thoracic surgeon [23]. Time to tracheostomy was defined as the duration between initiating MV care and tracheostomy. According to tracheostomy guidelines from the Korean Bronchoesophagological Society, early tracheostomy (ET) was defined as a tracheostomy within 7 days after tracheal intubation, and late tracheostomy (LT) was defined as a tracheostomy after 7 days [24]. The 90-day cumulative mortality rate was calculated from the first day of MV. For surviving patients discharged from the hospital, the mortality rate was obtained from the National Health Insurance Service Database [25]. Total medical expenditures for all medical resources used during the hospitalization were retrieved with the permission of the Institutional Review Board (IRB). All costs are shown in United States Dollars (USD) at an exchange rate of 1 USD = 1,357.30 Korean won (exchange rate on November 1, 2023).

Continuous variables were presented as the mean ┬▒ standard deviation or median (interquartile range) and compared using the Student t-test or MannŌĆōWhitney U test, as applicable. Categorical variables were presented as numbers (percentages) and compared using the chi-square or FisherŌĆÖs exact test, as applicable. Survival analysis was performed to compare the survival time between the two groups, and the difference in KaplanŌĆōMeier curves between the groups was assessed using the log-rank test.

To minimize potential selection bias due to the absence of randomization between the tracheostomy and no-tracheostomy groups, as well as between the ET and LT groups, PSM was performed using 1-to-1 nearest-neighbor matching without replacement. Propensity scores were calculated using the following covariates; age, sex, BMI, comorbidities, APACHE II score, SOFA score, CCI, and use of adjunctive therapy (vasopressor, neuromuscular blocking agents, and renal replacement therapy). The propensity score was estimated via logistic regression. In this process, all patients were categorized based on the propensity scores, and each group was matched within 0.2 standard deviations of the logit propensity score [26]. Subgroup analysis after PSM was conducted based on age, sex, BMI, CCI, APACHE II score, SOFA score, and ICU admission year to identify factors affecting the occurrence of 90-day cumulative mortality.

Health ratio indicators were collected using the following variables: (1) number of active beds, which refers to the number of functional beds for each hospital year; (2) active bed days, which refers to the number of functional beds in the hospital for a given period, usually 1 year, calculated as the number of active beds multiplied by 365 days; (3) number of discharges in a given year; and (4) occupied bed days, which refers to the sum of the total number of days all admitted patients spent in the hospital for a given year. Using the above variables, four ratios or indices were computed as follows:

All tests were two-tailed and p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical language (version 4.3.2; R Core Team, 2023) and additional packages (MatchIt).

Approval of the IRB of Pusan National University Hospital was obtained, and the need for patient consent was waived because of the retrospective and observational nature of the study (IRB No. 2403-009-137). Study procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines [27,28].

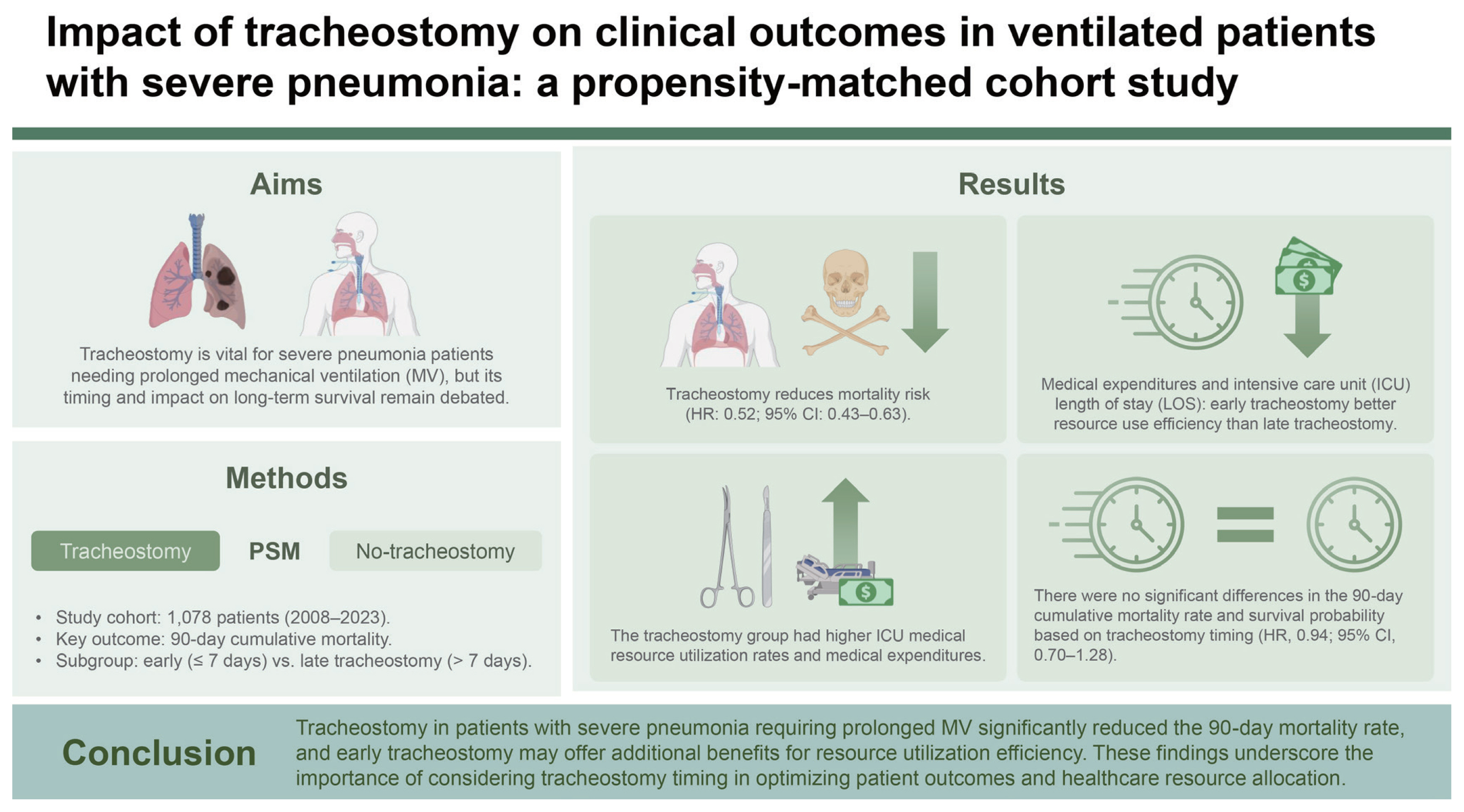

During the study period, 3,296 patients underwent MV in the respiratory ICU, with 1,675 (50.8%) requiring PAMV. In total, 277 patients who received MV for reasons other than pneumonia, 241 patients who had limited life-sustaining treatments, and 79 who had a tracheostomy before ICU admission were excluded. The final study cohort comprised 1,078 patients (Fig. 1). In the entire population, the ICU, hospital, and 90-day cumulative mortality rates were 30.1% (n = 325), 36.1% (n = 389), and 47.6% (n = 513), respectively. In total, 545 patients (50.6%) underwent tracheostomy during the ICU stay, and the median time to tracheostomy was 7 days (range, 0ŌĆō44 days) (Fig. 2).

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study cohort before and after PSM. At ICU admission, the tracheostomy group was older and had a higher CCI than the no-tracheostomy group. In PSM analysis, 914 patients with and without tracheostomy were matched (n = 457 per group). The selected covariates did not significantly differ between the matched groups (all standardized mean differences < 0.2), with histograms of the logit of propensity scores demonstrating the high quality of the matching process (Supplementary Fig. 1). The tracheostomy group experienced significantly longer durations of MV as well as ICU and hospital LOS than the no-tracheostomy group. Furthermore, the tracheostomy group had significantly lower ICU, hospital, and 90-day cumulative mortality rates. However, the tracheostomy group had a significantly higher transfer rate to step-down hospitals compared to the no-tracheostomy group (55.1% vs. 28.0%, p < 0.001). Additionally, the tracheostomy group had higher medical expenditures, BOR, and average LOS than the no-tracheostomy group (Table 2).

Survival analysis indicated that over 90 days, the tracheostomy group had a higher survival probability than the no-tracheostomy group (hazard ratio [HR] 0.52, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.43ŌĆō0.63) (Fig. 3A). Subgroup analysis showed that in all cases, the tracheostomy group had a lower 90-day cumulative mortality rate than the no-tracheostomy group (Fig. 4A).

In the tracheostomy group, 275 patients were classified into the ET group, while 270 patients were classified into the LT group. After PSM, 205 patients in each of the ET and LT groups were matched. Table 3 summarizes the baseline characteristics of patients classified according to the timing of tracheostomy. The selected covariates did not significantly differ between the matched ET and LT groups (all standardized mean differences < 0.2), with histograms of the logit of propensity scores demonstrating the high quality of the matching process (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The ET group had significantly shorter durations of MV, ICU LOS, and hospital LOS and incurred lower medical expenditures than the LT group (Table 4). However, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of discharge outcomes, decannulation rates, 90-day cumulative mortality rate, or survival (HR 0.94, 95% CI 0.70ŌĆō1.28) (Fig. 3B). Additionally, the mortality rate did not significantly differ between the two groups in all subgroup analyses (Fig. 4B).

This study is the first investigation to assess the influence of tracheostomy on 90-day outcomes among PAMV patients with severe pneumonia, while also exploring the distinctions between ET and LT following Korean guidelines, using PSM analysis. Our findings provide critical care physicians with valuable insights into the role of tracheostomy in planning long-term strategies for patients with severe pneumonia who require prolonged MV.

A key aspect of our study was the examination of positive outcomes associated with tracheostomy using PSM analysis. Our findings revealed that patients who underwent tracheostomy had a lower 90-day mortality rate. This survival benefit was consistent across all subgroups, irrespective of factors such as age, sex, severity, comorbidities, and presence of organ failure at ICU admission. The improved outcomes may be attributable to various advantages of tracheostomy, including improvements in lung mechanics, easier oral hygiene management, reduced sedative usage promoting easier expectoration by patients, and a subsequent decrease in the risk of VAP [5,29,30]. However, patients who underwent tracheostomy have longer LOS, higher medical expenditures, and often require long-term care facilities for additional respiratory and swallowing rehabilitation [31,32]. Tracheostomy should be considered for patients who have difficulty being liberated from MV, as indicated by various clinical indicators [33,34]. Our findings also suggest that tracheostomy can play a crucial role in managing critically ill patients with acute respiratory failure due to severe pneumonia and highlight the need for appropriate allocation of medical resources during tracheostomy.

Previous studies produced varied conclusions regarding the survival benefits of tracheostomy in patients requiring prolonged MV [8,9,30,35]. By contrast, our study indicates that tracheostomy may offer notable benefits for patients with severe pneumonia requiring prolonged MV. These differences might be attributable to the heterogeneity in the enrolled subjects whose data were reported [5,36], which often included subgroups with diverse etiological conditions requiring MV and different ICU environments. Our study focused exclusively on patients with severe pneumonia in a respiratory ICU. By focusing on a more homogeneous patient population, the present study provides clearer insights into the benefits of tracheostomy for severe pneumonia patients receiving prolonged MV.

Although the timing of tracheostomy did not demonstrate a survival benefit according to our national guidelines [24], ET positively influenced ICU capacity by alleviating strain. This led to lower medical expenditures. Therefore, ET could help to optimize the clinical course and manage critical care resources [37]. Given the current state of critical care medicine in Korea, which is characterized by a chronic shortage of ICU beds relative to hospital size and a lack of nursing staff, full-time intensivists, and well-designed MV weaning protocols [38,39], the decision by attending physicians to perform ET may be advantageous for patients anticipated to require long-term ventilator care upon ICU admission. Despite potential adverse effects of tracheostomy, such as procedure-related complications and later cosmetic concerns [40,41], ET could offer significant benefits in terms of resource management and long-term patient care. However, our findings are based on a single institution; therefore, larger multi-center studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of ET in terms of patient outcomes. Future research should also consider the cost-effectiveness and long-term benefits of ET across various patient populations and healthcare settings to provide a more comprehensive understanding of its impact.

The optimal timing of tracheostomy remains controversial, with criteria for ET and LT varying between studies [5,10]. Currently, there is no international guideline that clearly defines the distinction between ET and LT, which leads to inconsistencies in clinical practice and research. Although Korea has established criteria for ET and LT, it is uncertain if these criteria are applicable to ventilated patients with severe pneumonia. Therefore, extensive large-scale, multicenter studies are necessary to evaluate the performance and optimal timing of tracheostomy. Essential considerations in these studies should include defining patient populations likely to require prolonged MV, establishing clear definitions of ET and LT, and assessing adverse events associated with tracheostomy. These studies will help determine whether the performance and timing of tracheostomy can be universally applied across different patient populations and healthcare settings, as well as their impact on outcomes such as survival, MV duration, and complication rates. This understanding is critical for improving clinical decision-making and patient care.

According to historical studies, tracheostomy was performed in 9ŌĆō13% of patients receiving MV [2,8]. One study reported that up to 34% of patients requiring MV for more than 48 hours underwent tracheostomy [42]. In our study, tracheostomy was performed in 16.5% of patients receiving MV and in 50.6% of those requiring MV for more than 96 hours, which is a higher rate than previously reported. This higher rate in our study may be explained by the fact that we focused on patients with severe respiratory failure due to severe pneumonia, and our patient population was older than in previous studies.

This study has several limitations. First, it is difficult to predict which patients will require prolonged MV or tracheostomy, and the subjects may be heterogeneous due to the diversity of underlying diseases and severity. We implemented PSM analysis to minimize potential selection bias related to the subjects and timing of tracheostomy. Second, this study was limited to data from a single institution, making it difficult to generalize the findings to the overall situation in South Korea. Third, we hypothesized that tracheostomy is associated with a decreased incidence of VAP, however, we could not definitively confirm the association between tracheostomy and VAP due to the retrospective design. Lastly, the clinical differences between community-acquired pneumonia and hospital-acquired pneumonia, as well as complications related to tracheostomy (such as bleeding, laryngeal damage, etc.), are important considerations in patient outcomes. However, the retrospective design of this study limited our ability to analyze these factors due to insufficient data accurately. Despite these limitations, our PSM analysis provides evidence that tracheostomy, when performed timely, can significantly reduce mortality and improve the efficiency of medical resource utilization, highlighting its value as a critical treatment strategy.

In conclusion, analysis of the effect of tracheostomy on outcomes of pneumonia patients showed that 90-day cumulative mortality was reduced. Additionally, the ET group had shorter durations of MV and LOS as well as lower medical expenditures than the LT group. To accurately assess the effect of tracheostomy on patient outcomes, large-scale, multi-center research tailored to the specific conditions of the healthcare environment is essential.

1. Tracheostomy reduces the 90-day cumulative mortality rate in severe pneumonia patients requiring prolonged MV.

2. ET has a positive impact on alleviating ICU capacity and reducing healthcare expenditures.

3. Considering tracheostomy may help manage resources and improve long-term patient outcomes, suggesting that it may be an important treatment strategy for severe pneumonia patients requiring prolonged MV.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Hayoung Seong: methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, software, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, visualization; Hyojin Jang: investigation, validation; Wanho Yoo: investigation, validation; Saerom Kim: investigation, validation; Soo Han Kim: investigation, validation; Kwangha Lee: conceptualization, methodology, resources, investigation, software, writing - review & editing, supervision

Figure┬Ā1

Patient selection flow chart. MV, mechanical ventilation; ICU, intensive care unit. a)Included leukemia, cardiomyopathy, pulmonary edema, arrhythmia, diabetic ketoacidosis, and connective tissue disease.

Figure┬Ā2

Distribution of time to tracheostomy (from mechanical ventilator care to tracheostomy) (n = 545).

Figure┬Ā3

KaplanŌĆōMeier survival curves of 90-day survival in (A) the matched tracheostomy and no-tracheostomy groups and (B) the matched early tracheostomy and late tracheostomy groups. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Figure┬Ā4

Subgroup analysis of 90-day mortality in (A) the matched tracheostomy and no-tracheostomy groups and (B) the matched early tracheostomy and late tracheostomy groups. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; CCI, CharlsonŌĆÖs comorbidity index; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; NA, not available.

Table┬Ā1

Comparison of baseline characteristics of patients in the tracheostomy and no-tracheostomy groups before and after propensity score matching

| Characteristic | Before matching | After matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Tracheostomy (n = 545) | No-tracheostomy (n = 533) | SMD | Tracheostomy (n = 457) | No-tracheostomy (n = 457) | SMD | |

| Age (yr) | 69.4 ┬▒ 12.8 | 66.7 ┬▒ 13.8 | 0.211 | 68.9 ┬▒ 12.6 | 68.3 ┬▒ 12.8 | 0.043 |

|

|

||||||

| Sex (male) | 389 (71.4) | 377 (70.7) | 0.006 | 327 (71.6) | 326 (71.3) | 0.002 |

|

|

||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.6 ┬▒ 3.7 | 22.1 ┬▒ 4.0 | 0.112 | 21.7 ┬▒ 3.6 | 22.0 ┬▒ 3.7 | 0.064 |

|

|

||||||

| CCI | 5.7 ┬▒ 3.0 | 5.1 ┬▒ 2.9 | 0.188 | 5.5 ┬▒ 2.9 | 5.4 ┬▒ 2.9 | 0.022 |

|

|

||||||

| APACHE II scorea) | 21.9 ┬▒ 6.8 | 21.3 ┬▒ 7.6 | 0.097 | 21.5 ┬▒ 6.7 | 21.7 ┬▒ 7.7 | 0.030 |

|

|

||||||

| SOFA scorea) | 7.9 ┬▒ 3.2 | 7.9 ┬▒ 3.7 | 0.004 | 7.9 ┬▒ 3.2 | 8.0 ┬▒ 3.7 | 0.033 |

|

|

||||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāPulmonologic | 303 (55.6) | 315 (59.1) | 0.035 | 274 (60.0) | 261 (57.1) | 0.028 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāHemato-oncologic | 81 (14.9) | 94 (17.6) | 0.028 | 71 (15.5) | 77 (16.8) | 0.013 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāCardiologic | 87 (16.0) | 57 (10.7) | 0.053 | 54 (11.8) | 54 (11.8) | 0.000 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāNeurologicb) | 87 (16.0) | 49 (9.2) | 0.068 | 47 (10.3) | 47 (10.3) | 0.000 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāNephrologic | 67 (12.3) | 76 (14.3) | 0.001 | 26 (5.7) | 27 (5.9) | 0.002 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāHepatologic | 10 (1.8) | 13 (2.4) | 0.006 | 10 (2.2) | 9 (2.0) | 0.002 |

|

|

||||||

| Adjunctive therapy | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāVasopressora) | 305 (56.0) | 328 (61.5) | 0.056 | 264 (57.8) | 265 (58.0) | 0.002 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāNMBAsa) | 291 (53.4) | 310 (58.2) | 0.048 | 250 (54.7) | 255 (55.8) | 0.011 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāRRTa) | 67 (12.3) | 76 (14.6) | 0.020 | 59 (12.9) | 62 (13.6) | 0.007 |

SMD, standardized mean difference; BMI, body mass index; CCI, CharlsonŌĆÖs comorbidity index; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; NMBA, neuromuscular blocking agent; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Table┬Ā2

Comparison of clinical outcomes of propensity-matched patients in the tracheostomy and no-tracheostomy groups

Table┬Ā3

Comparison of baseline characteristics of patients in the ET and LT groups before and after propensity score matching

| Characteristic | Before matching | After matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| ET (n = 275) | LT (n = 270) | SMD | ET (n = 205) | LT (n = 205) | SMD | |

| Age (years) | 71.8 ┬▒ 10.8 | 66.9 ┬▒ 14.1 | 0.451 | 71.1 ┬▒ 11.6 | 70.3 ┬▒ 10.8 | 0.077 |

|

|

||||||

| Sex (male) | 200 (72.7) | 189 (70.0) | 0.027 | 143 (69.8) | 145 (70.7) | 0.010 |

|

|

||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.7 ┬▒ 3.8 | 21.6 ┬▒ 3.5 | 0.001 | 21.6 ┬▒ 4.1 | 21.8 ┬▒ 3.6 | 0.050 |

|

|

||||||

| CCI | 5.9 ┬▒ 3.2 | 5.4 ┬▒ 2.9 | 0.177 | 5.9 ┬▒ 3.2 | 5.7 ┬▒ 2.7 | 0.060 |

|

|

||||||

| APACHE II scorea) | 21.1 ┬▒ 6.5 | 22.8 ┬▒ 7.0 | 0.270 | 21.8 ┬▒ 6.6 | 21.7 ┬▒ 6.2 | 0.008 |

|

|

||||||

| SOFA scorea) | 7.7 ┬▒ 3.0 | 8.2 ┬▒ 3.4 | 0.150 | 7.8 ┬▒ 3.0 | 7.8 ┬▒ 3.2 | 0.016 |

|

|

||||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāPulmonologic | 149 (54.2) | 154 (57.0) | 0.029 | 117 (57.1) | 118 (57.6) | 0.005 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāHemato-oncologic | 44 (16.0) | 37 (13.7) | 0.023 | 29 (14.1) | 27 (13.2) | 0.010 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāCardiologic | 42 (15.3) | 45 (16.7) | 0.014 | 34 (16.6) | 31 (15.1) | 0.015 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāNeurologicb) | 44 (16.0) | 43 (15.9) | 0.001 | 32 (15.6) | 32 (15.6) | 0.000 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāNephrologic | 14 (5.1) | 18 (6.7) | 0.016 | 10 (4.9) | 10 (4.9) | 0.005 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāHepatologic | 4 (1.5) | 6 (2.2) | 0.008 | 4 (2.0) | 4 (2.0) | 0.000 |

|

|

||||||

| Adjunctive therapy | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāVasopressora) | 163 (59.3) | 142 (52.6) | 0.067 | 119 (58.0) | 117 (57.1) | 0.010 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāNMBAsa) | 155 (56.4) | 136 (50.4) | 0.060 | 113 (55.1) | 104 (50.7) | 0.010 |

|

|

||||||

| ŌĆāRRTa) | 30 (10.9) | 37 (13.7) | 0.028 | 25 (12.2) | 23 (11.2) | 0.044 |

ET, early tracheostomy; LT, late tracheostomy; SMD, standardized mean difference; BMI, body mass index; CCI, CharlsonŌĆÖs comorbidity index; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; NMBA, neuromuscular blocking agent; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Table┬Ā4

Comparison of clinical outcomes of propensity-matched patients in the ET and LT groups

REFERENCES

1. Law AC, Tian W, Song Y, Stevens JP, Walkey AJ. Decline in prolonged acute mechanical ventilation, 2011ŌĆō2019. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022;206:640ŌĆō644.

2. Mehta AB, Syeda SN, Wiener RS, Walkey AJ. Epidemiological trends in invasive mechanical ventilation in the United States: a population-based study. J Crit Care 2015;30:1217ŌĆō1221.

3. Fagon JY, Chastre J, Vuagnat A, Trouillet JL, Novara A, Gibert C. Nosocomial pneumonia and mortality among patients in intensive care units. JAMA 1996;275:866ŌĆō869.

4. Holzapfel L, Chevret S, Madinier G, et al. Influence of long-term oro- or nasotracheal intubation on nosocomial maxillary sinusitis and pneumonia: results of a prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Crit Care Med 1993;21:1132ŌĆō1138.

6. Whitmore KA, Townsend SC, Laupland KB. Management of tracheostomies in the intensive care unit: a scoping review. BMJ Open Respir Res 2020;7:e000651.

7. Quinn L, Veenith T, Bion J, Hemming K, Whitehouse T, Lilford R. Bayesian analysis of a systematic review of early versus late tracheostomy in ICU patients. Br J Anaesth 2022;129:693ŌĆō702.

8. Abe T, Madotto F, Pham T, et al. Epidemiology and patterns of tracheostomy practice in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in ICUs across 50 countries. Crit Care 2018;22:195.

9. ClecŌĆÖh C, Alberti C, Vincent F, et al. Tracheostomy does not improve the outcome of patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: a propensity analysis. Crit Care Med 2007;35:132ŌĆō138.

10. Aquino Esperanza J, Pelosi P, Blanch L. WhatŌĆÖs new in intensive care: tracheostomy-what is known and what remains to be determined. Intensive Care Med 2019;45:1619ŌĆō1621.

11. Rose L, Messer B. Prolonged mechanical ventilation, weaning, and the role of tracheostomy. Crit Care Clin 2024;40:409ŌĆō427.

12. Oh TK, Kim HG, Song IA. Epidemiologic study of intensive care unit admission in South Korea: a nationwide population-based cohort study from 2010 to 2019. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;20:81.

13. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1301ŌĆō1308.

15. Lanks CW, Musani AI, Hsia DW. Community-acquired pneumonia and hospital-acquired pneumonia. Med Clin North Am 2019;103:487ŌĆō501.

16. Zilberberg MD, Nathanson BH, Ways J, Shorr AF. Characteristics, hospital course, and outcomes of patients requiring prolonged acute versus short-term mechanical ventilation in the United States, 2014ŌĆō2018. Crit Care Med 2020;48:1587ŌĆō1594.

17. Mehrtak M, Yusefzadeh H, Jaafaripooyan E. Pabon Lasso and Data Envelopment Analysis: a complementary approach to hospital performance measurement. Glob J Health Sci 2014;6:107ŌĆō116.

18. Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine beds, use, occupancy, and costs in the United States: a methodological review. Crit Care Med 2015;43:2452ŌĆō2459.

19. Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000ŌĆō2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med 2010;38:65ŌĆō71.

20. Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985;13:818ŌĆō829.

21. Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/ failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:707ŌĆō710.

22. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373ŌĆō383.

23. Landa K, Pappas TN. ZollingerŌĆÖs atlas of surgical operations, 11th edition. Ann Surg 2023;277:e488.

24. Korean Bronchoesophagological Society Guideline Task Force; Nam IC, et al.; Shin YS. Guidelines for tracheostomy from the Korean Bronchoesophagological Society. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2020;13:361ŌĆō375.

25. Seong SC, Kim YY, Khang YH, et al. Data resource profile: the National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:799ŌĆō800.

26. Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat 2011;10:150ŌĆō161.

27. World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191ŌĆō2194.

28. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453ŌĆō1457.

29. Freeman BD, Morris PE. Tracheostomy practice in adults with acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2890ŌĆō2896.

30. Combes A, Luyt CE, Nieszkowska A, Trouillet JL, Gibert C, Chastre J. Is tracheostomy associated with better outcomes for patients requiring long-term mechanical ventilation? Crit Care Med 2007;35:802ŌĆō807.

31. Ishizaki M, Toyama M, Imura H, Takahashi Y, Nakayama T. Tracheostomy decannulation rates in Japan: a retrospective cohort study using a claims database. Sci Rep 2022;12:19801.

32. Cox CE, Carson SS, Lindquist JH, Olsen MK, Govert JA, Chelluri L. Differences in one-year health outcomes and resource utilization by definition of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care 2007;11:R9.

33. MacIntyre NR. The ventilator discontinuation process: an expanding evidence base. Respir Care 2013;58:1074ŌĆō1086.

34. Jeong ES, Lee K. Clinical application of modified Burns Wean Assessment Program scores at first spontaneous breathing trial in weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. Acute Crit Care 2018;33:260ŌĆō268.

35. Cinotti R, Voicu S, Jaber S, et al. Tracheostomy and long-term mortality in ICU patients undergoing prolonged mechanical ventilation. PLoS One 2019;14:e0220399.

36. Raimondi N, Vial MR, Calleja J, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the use of tracheostomy in critically ill patients. J Crit Care 2017;38:304ŌĆō318.

37. Hernandez G, Ramos FJ, A├▒on JM, et al. Early tracheostomy for managing ICU capacity during the COVID-19 outbreak: a propensity-matched cohort study. Chest 2022;161:121ŌĆō129.

38. Lim CM, Kwak SH, Suh GY, Koh Y. Critical care in Korea: present and future. J Korean Med Sci 2015;30:1540ŌĆō1544.

39. Kwak SH, Jeong CW, Lee SH, Lee HJ, Koh Y. Current status of intensive care units registered as critical care subspecialty training hospitals in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2014;29:431ŌĆō437.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement figure 1

Supplement figure 1 Print

Print