|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 39(6); 2024 > Article |

|

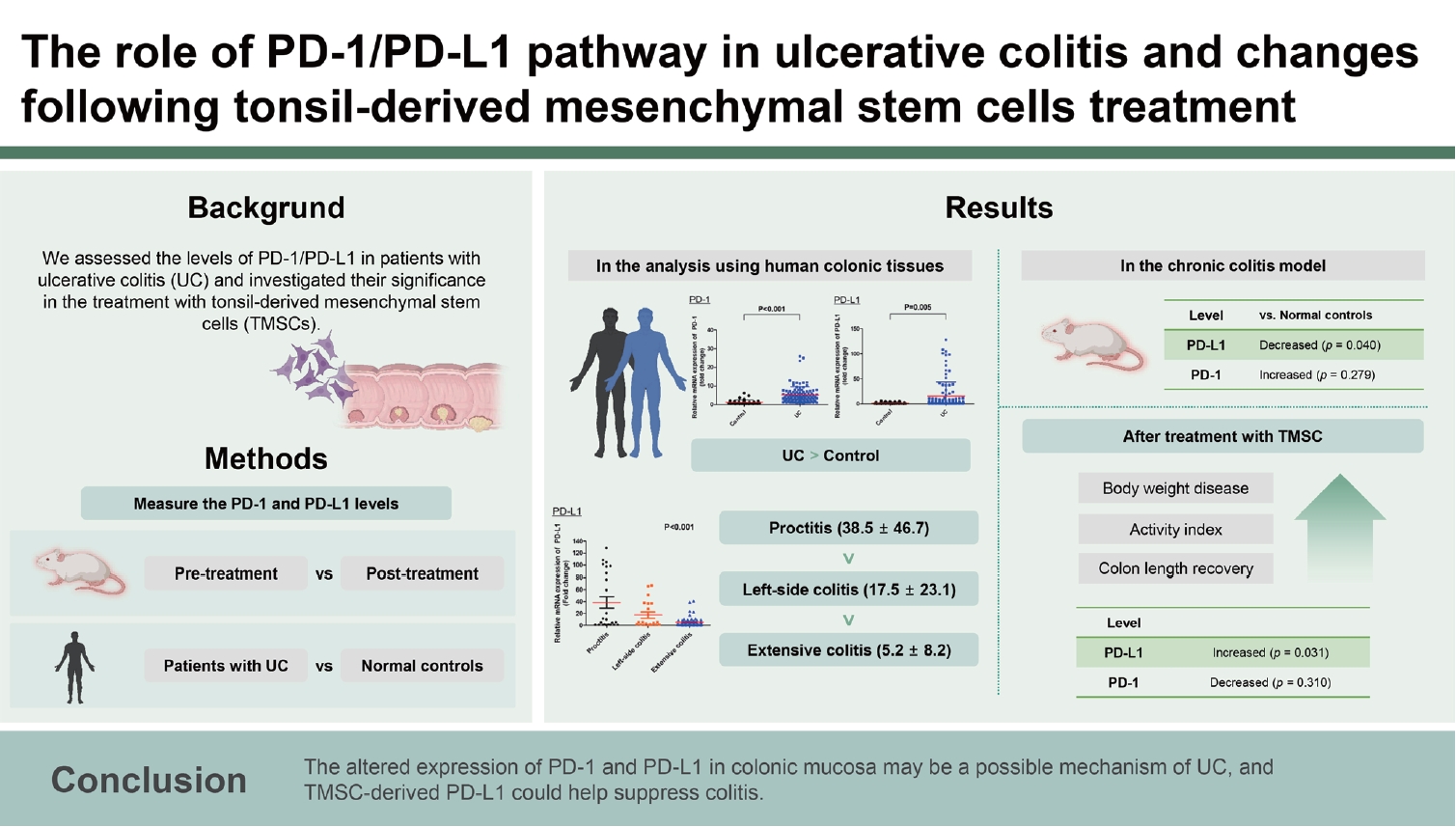

Abstract

Background/Aims

The programmed death 1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway has not been fully evaluated in inflammatory bowel disease. We evaluated PD-1/PD-L1 levels in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and their significance in tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells (TMSCs) treatment.

Methods

Using acute and chronic murine colitis model, we measured the PD-1 and PD-L1 levels in inflamed colonic tissues pre- and post-treatment with TMSCs. We also measured PD-1 and PD-L1 levels in colonic tissues from UC patients, compared to normal controls.

Results

In the analysis using human colonic tissues, a significant increase in the levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 was observed in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC compared with normal controls (p < 0.001 and p = 0.005, respectively). When comparing the maximal disease extent, PD-L1 levels were highest in patients with proctitis (38.5 ± 46.7), followed by left-side colitis (17.5 ± 23.1) and extensive colitis (5.2 ± 8.2) (p < 0.001). In the chronic colitis model, the level of PD-L1 was decreased (p = 0.040) and the level of PD-1 increased more than in normal controls (p = 0.047). After treatment with TMSC, significant improvements were observed in body weight, disease activity index, and colon length recovery. Additionally, the levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 were recovered; PD-L1 significantly increased (p = 0.031), while the level of PD-1 decreased (p = 0.310).

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), is a chronic relapsing-remitting disease. The incidence of IBD has risen rapidly in Asian countries, including Korea [1]. In a recent Korean population-based cohort study, the annual incidence rates of CD and UC per 100,000 inhabitants gradually increased from 0.6 and 0.29 in 1986–1990 to 2.44 and 5.82 in 2011–2015, respectively [2]. Despite decades of research, the pathogenesis of IBD remains largely unknown. Some researchers believe that abnormal immune responses accompanied by genetic, environmental, and gut microbial factors are among the main factors in IBD development [3].

Programmed death 1 (PD-1), a member of the B7-CD28 family, is a co-inhibitory receptor expressed on B cells, T cells, monocytes, and natural killer cells. Interaction of PD-1 and its ligand programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) exerts a wide range of immunoregulatory functions in T cell activation, immune tolerance, and autoimmunity [3]. Engagement of PD-L1 or PD-L2 with PD-1 on T cells leads to the downregulation of T cell responses by mediating programmed cell death and inhibiting cytokine secretions [4]. Meanwhile, anti-PD-L1 antibodies, which block the PD-L1 ligation on PD-1 are being successfully used to treat several solid tumors, prevent suppression of active T cells, and cause the development of severe enterocolitis mimicking IBD as a serious adverse event [5].

Although the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may play a role in IBD pathogenesis, the underlying mechanism remains poorly characterized. Beswick et al. [6] reported that the PD-1 level is increased in T cells in the inflamed colon mucosa of patients with IBD. Scandiuzzi et al. demonstrated that PD-L1 expressed in gut epithelium regulates intestinal inflammation by inhibiting innate immune cells. Furthermore, the decreased PD-L1 expression in the colonic mucosa of patients with CD was also reported to contribute to the dysregulation of Th1 response and aggravation of mucosal inflammation in patients with CD [7,8]. In addition, PD-1 deficient mice showed resistance to experimental colitis through alteration of gut microbiota [9].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are pluripotent stem cells that can be isolated from the bone marrow, fat, skin, amniotic fluid, and umbilical cord blood and have been evaluated as a potential therapeutic alternative for several autoimmune diseases, including IBD, owing to their immunosuppressive and tissue-regenerative properties [10,11]. Tonsil-derived MSCs (TMSCs) have been proposed as a new source of MSCs as they proliferate and are easily obtainable [12,13]. In our previous studies, administration of TMSCs and TMSC-conditioned medium in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced acute and chronic murine colitis models demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in terms of lowering disease activity index (DAI) scores, colon length recovery, and decreased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [14,15].

In this study, we evaluated the relative gene expression levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 in the colonic mucosa with and without active inflammation in patients with UC, as well as in TMSC, which are therapeutically effective in a murine colitis model. Additionally, we evaluated the changes in PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in a murine colitis model with and without TMSCs treatment.

At our center, we have maintained the Ewha IBD cohort since 2019, prospectively collecting patient data, colon biopsy specimen, blood, and stool sample. Between December 2020 and December 2021, we enrolled 14 patients with UC and 18 normal controls. After obtaining informed consent from patients under the approved human research protocol of the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital (IRB number, SEUMC 2020-12-017), endoscopic colonic biopsies were performed at each five segments of the colon in patients with IBD and at 2–3 segments of the colon in normal controls. Additionally, we analyzed seven colon specimens collected from the Ewha IBD cohort (SEUMC 2019-04-019). Detailed demographic and clinical data were retrieved from medical record. Throughout the study, the authors did not have access to information that could identify individual participants.

The colon biopsy specimens were immediately placed into RNA later (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and stored at -80°C for analysis. One milliliter of TRIzol Reagent (Ambion, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was added to the colon specimen. After mincing, 200 μL of chloroform (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added, followed by vortexing. The mixture was then centrifuged, and the supernatants were transferred to a new tube. An equal volume of isopropanol (Sigma) was added; after mixing by inversion, the sample was centrifuged again at 13,000 ×g (4°C) for 10 minutes. Subsequently, nuclease-free water was added, and the RNA concentration was measured using Nabi (NanoDrop) (MicroDigital, Seongnam, Korea), followed by the mixture of 2 μg of RNA and 0.5 μg of oligo dT primer, where the sample was left at 70°C for 10 minutes thereafter. Next, 200 units of Molony Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase (M-MLV RT) (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA), 25 units of rRNasin Ribonuclease inhibitor (Promega), 5 × RT buffer, and 2 mM of dNTP were added, and the final volume was set to 25 μL by adding an appropriate amount of nuclease-free water. A Quantstudio 3 real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for analysis using 0.1 μg of the synthesized cDNA as a template for the 2X Power SYBR Green PCR Master mix (Applied Biosystems) and each primer set for PD-1 and PDL1. Primers used in this study were obtained from Macrogen (Seoul, Korea) (Table 1). Each PCR was performed after 10 minutes of pre-denaturation at 95°C, 15 seconds at 95°C, and 1 minute at 60°C; this was repeated 40 times. After the PCR was completed, a melting curve was drawn to check the accuracy of gene amplification. For the internal compensation of gene expression level, the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was also used, and relative gene expression levels were presented as 2-ΔΔCt values.

Participants aged < 18 years were recruited for this study. Written informed consents were obtained from the legal guardians of the parents and/or patients for tonsil tissue studies. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University Medical Center (ECT 11-53-02). All experiments were performed following institutional ethical guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. All the tonsil tissues used in this study were obtained from a single donor. TMSCs were isolated and cultured as described in our previous studies [14]. Tonsil tissues were obtained during tonsillectomy from patients under 10 years of age. Minced and digested tonsillar tissues were washed using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium-high glucose (DMEM-HG; Welgene, Daegu, Korea) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen) and washed again using DMEM-HG supplemented with 10% FBS. Mononuclear cells were isolated from the prepared tonsil tissues and cultured in cell culture plates. The adherent cells were further cultured for 2 weeks and passaged. The passaged cells (hereafter referred to as TMSCs) were stored in liquid nitrogen for future experiments. The MSC characteristics of TMSCs, according to the minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells [16], were confirmed in our previous study [14] and other studies [17].

PD-1 and PD-L1 expression was measured in TMSCs. PD-1 was measured exclusively on the cell surface, while PD-L1 was secreted in soluble form in the conditioned medium and on the cell surface. PD-1 and PD-L1 expression on the surface of TMSC was also measured. The mRNA expression level of PD-1 and PD-L1 on the surface of TMSC were confirmed real-time PCR in the same procedure as previously described, and the soluble PD-L1 secreted from TMSC was confirmed by immunoassay. To measure PD-L1 (soluble form) secreted from TMSCs, TMSCs were sub-cultured and supernatants were collected and stored at -20°C or below before measurement. Extracted TMSC supernatants was used to measure PD-L1 levels using Quantikine Human PDL1 immunoassays (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The diluted sample (supernatant, lysate protein) and standard solution were incubated in each 96-well plate coated with PD-L1 antibody for 2 hours at room temperature on a shaker at 500 rpm. After the reaction in each well, the remaining solution was washed with Wash Buffer and aspirated. A 200 μL PD-L1 conjugate was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. After repeating the washing process, 200 μL of substrate solution was added and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with light blocking. After the reaction was complete, the color was developed with 50 μL of stop solution, and the optical density was measured within 30 min using a microplate reader set to 450 nm.

The animal models used for the experiment were sevenweek-old C57BL/6 male mice (Orient Bio Co., Ltd., Sungnam, Korea) with an average weight of 20–22 g. The mice were acclimatized for seven days in a standardized environment at the facility of the Ewha Womans University Medical Research Institute before the experiment. Day and night conditions were provided at 12 hours intervals, and the temperature (23 ± 2°C) and humidity (45–55%) were set to appropriate levels. Experiments and procedures were approved and all experiments were performed following experimental research protocol approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Research of Ewha Womans University (EUM19-0464, ESM18-0415). This study was performed following the standards described in ARRIVE guidelines. Acute colitis in mice was induced by oral administration of 2.5% DSS (MP Biochemical, Irvine, CA, USA) for seven days. Chronic colitis in mice was induced by oral administration of 1.5% DSS for five days, followed by an additional five days of tap water feeding; overall three such cycles (total 30 days) were performed. On the 7th day of the experiment after colitis induction in the acute colitis model and the 31st day of the experiment after colitis induction in the chronic colitis model, the mice were sacrificed by carbon dioxide inhalation, and the colon was dissected from the cecum to the anus for colon length measurement. Colon specimens of mice with colitis were also treated in the same manner as humans, and the levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 were measured using the method described above (Table 1).

In the acute colitis model, mice were randomly assigned to four groups: 1) normal control (n = 5), 2) TMSC control (n = 5), 3) DSS + phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) group (n = 5), and 4) TMSC-treated group (n = 5). TMSC was administered on day 3 following colitis induction in the TMSC-treated group, while in the TMSC control group, TMSC was administered on day 3 of the experiment without colitis induction. In the chronic colitis model, mice were randomly assigned to four groups: 1) normal control (n = 5), 2) TMSC control (n = 5), 3) DSS+PBS group (n = 5), and 4) TMSC-treated group (n = 10). In the TMSC-treated group, TMSC was administered on days 6, 9, 12, and 16 following colitis induction, while in the TMSC control group, TMSC was administered on days 6, 9, 12, and 16 of the experiment without colitis induction. For each group, weight change, stool consistency, and occult or grossly observed blood from stool or anus were checked daily and the DAI was assessed. The expression of PD-1, PD-L1, proinflammatory cytokine (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor-α [TNFα]) in colonic tissue were also measured as the method described previously (Table 1).

Categorical variables were presented as numbers with percentages, and continuous variables were presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables, and the Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables. All measured values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the values between the two groups. The statistical significance was set at a p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

To evaluate the role of PD-1 and PD-L1 in the pathogenesis of UC, we measured the expression levels of PD-1 and PDL1 in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC and compared them with those of the normal controls. A total of 21 patients with UC and 18 normal controls were enrolled. The median age at colonoscopy was 37.0 years (IQR, 26.5–58.0 yr) in patients with UC and 51.5 years (IQR, 35.0–60.0 yr) in the normal controls (p = 0.071) (Table 2). A total of 15 males (71.4%) and six females (28.6%) with UC were evaluated, and the proportion of female patients was significantly higher in the normal controls (p = 0.026). The maximal disease extent of enrolled UC patients was proctitis in five patients (23.8%), left-side colitis in four patients (19.0%), and extensive colitis in 12 patients (57.1%). Regarding endoscopic disease activity assessed using the Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES), six patients (28.6%) with UC were MES 0, ten (47.6%) were MES 1, four (19.0%) were MES 2, and one (4.8%) was MES 3. Regarding the patients’ medical history, 5-aminosalicylic acid was described in 20 patients (95.2%), immunomodulators in nine (42.9%), anti-TNF agents in six (28.6%), and small molecules in two (9.5%) (Table 2).

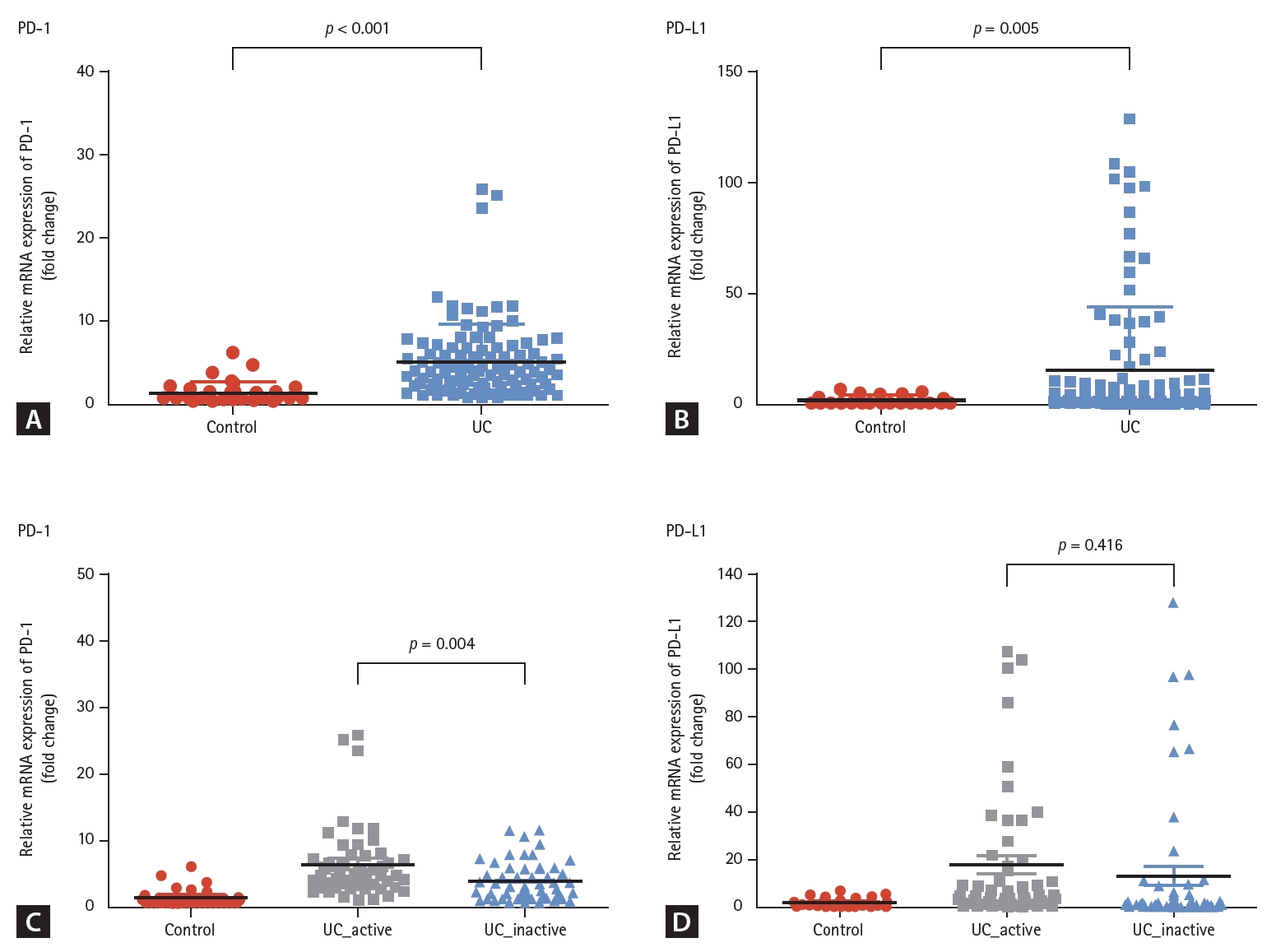

The expression of PD-1 was significantly increased in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC compared to that of normal controls (5.1 ± 4.5 vs. 1.3 ± 1.3, p < 0.001, Fig. 1A). Additionally, the expression of PD-L1 was also significantly increased in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC than that of normal controls (15.3 ± 28.5 vs. 1.7 ± 1.7, p = 0.005, Fig. 1B). To evaluate the association between PD-1 and PD-L1 expression and active inflammation in the colon, we compared the levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC with and without active inflammation. The expression of PD-1 was significantly higher in the colonic mucosa with active inflammation than in the colonic mucosa without active inflammation (6.3 ± 3.8 vs. 3.8 ± 2.9, p = 0.004, Fig. 1C) in patients with UC. However, no significant difference was observed in the level of PD-L1 between the mucosa with active inflammation and without active inflammation (17.6 ± 28.0 vs. 13.0 ± 29.0, p = 0.416, Fig. 1D).

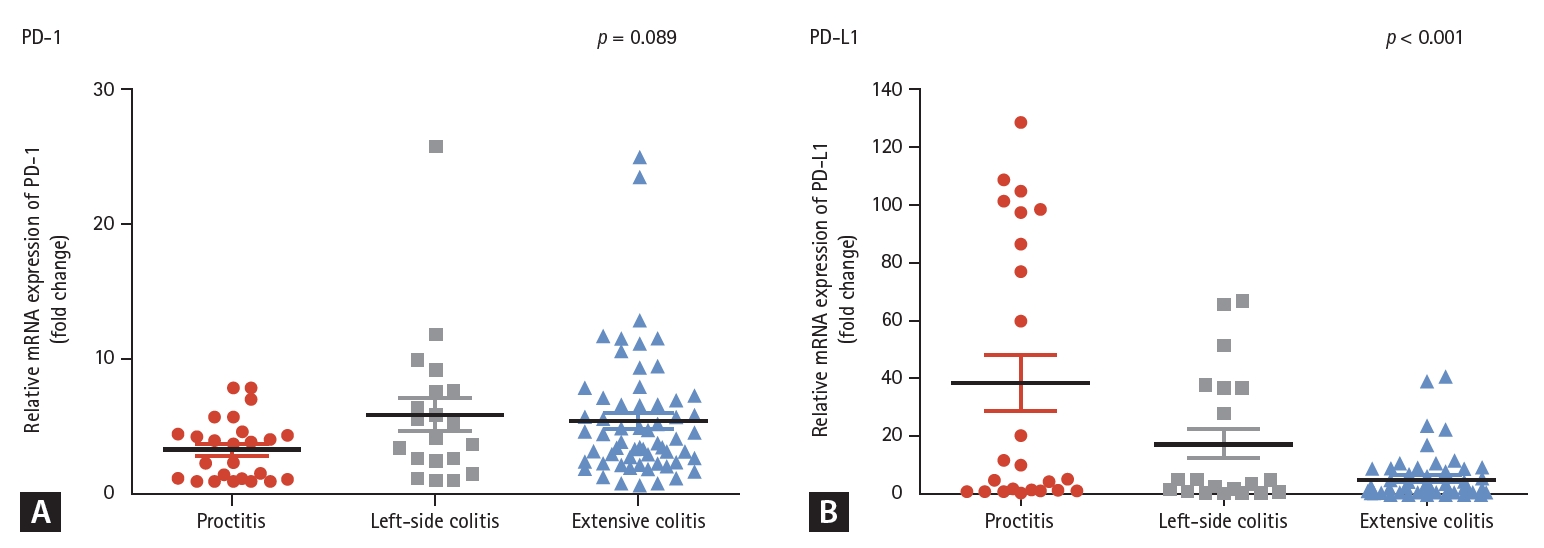

When comparing the maximal disease extent, the level of PD-L1 was found to be highest in patients with proctitis (38.5 ± 46.7), followed by left-side colitis (17.5 ± 23.1), and extensive colitis (5.2 ± 8.2) (p < 0.001, Fig. 2B). However, the level of PD-1 was not significantly different according to the maximal disease extent (3.4 ± 2.3 in proctitis, 6.0 ± 5.6 in left-side colitis, and 5.5 ± 4.7 in extensive colitis; p = 0.089) (Fig. 2A). When comparing the PD-1 and PD-L1 levels specifically from rectal mucosa, a difference was also observed, although these were not statistically significant (PD-1 level: proctitis 4.7 ± 2.5 vs. left-sided colitis 11.4 ± 10.3 vs. extensive colitis 9.0 ± 8.0; p = 0.318) (PD-L1 level: proctitis 42.3 ± 55.2 vs. left-sided colitis 29.4 ± 20.8 vs. extensive colitis 7.1 ± 6.1; p = 0.559). When comparing the levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 based on the disease extent while distinguishing between mucosa with and without active inflammation, we observed a decrease in the PD-L1 levels with increasing disease extent in both analyses. However, this difference was found to be more pronounced in mucosa with active inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 1). Otherwise, the levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 did not differ significantly based on disease activity or medication use.

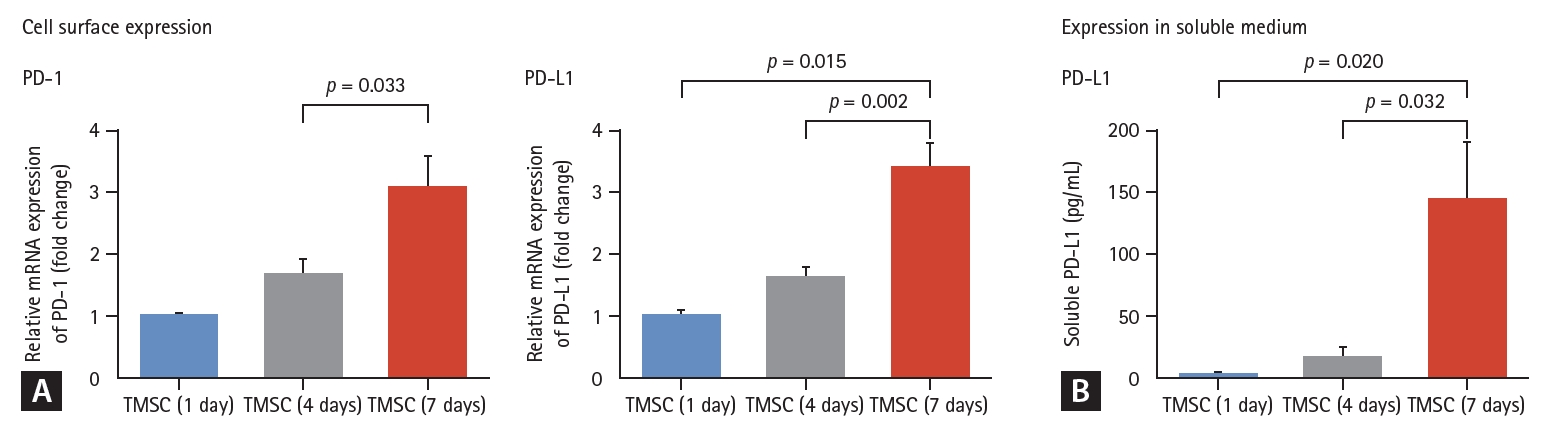

To evaluate whether the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway plays a role in the therapeutic effect of TMSCs, we measured the levels of PD-1 in cell lysate of TMSCs and PD-L1 in soluble medium and cell lysate of TMSCs. The surface expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 increased after seven days of differentiation (Fig. 3A). Additionally, we found that the PD-L1 was expressed in both forms of TMSCs (182.63 pg/mL in soluble medium and 11.85 pg/protein [μg] in cell lysate after seven days of differentiation period) (Fig. 3B).

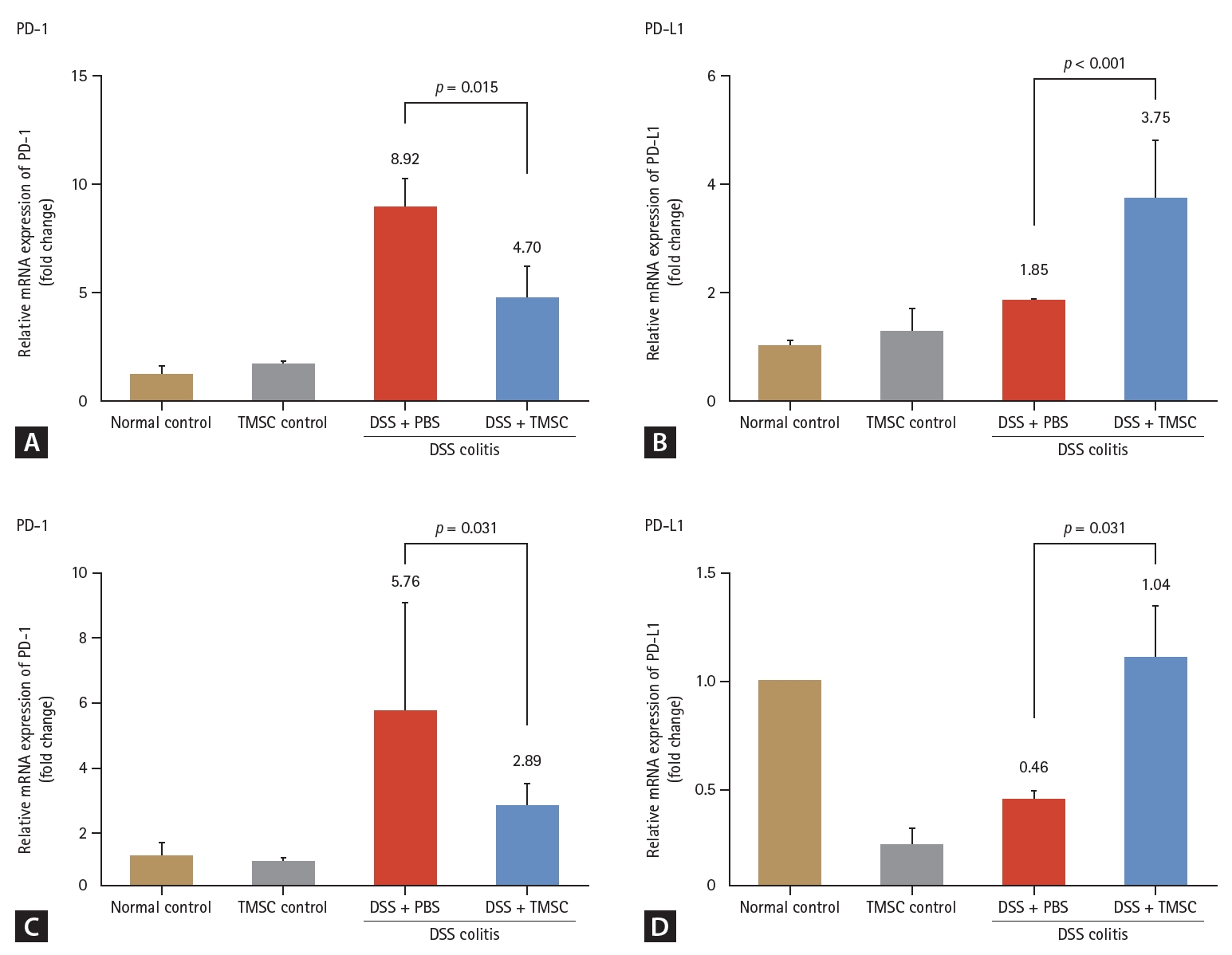

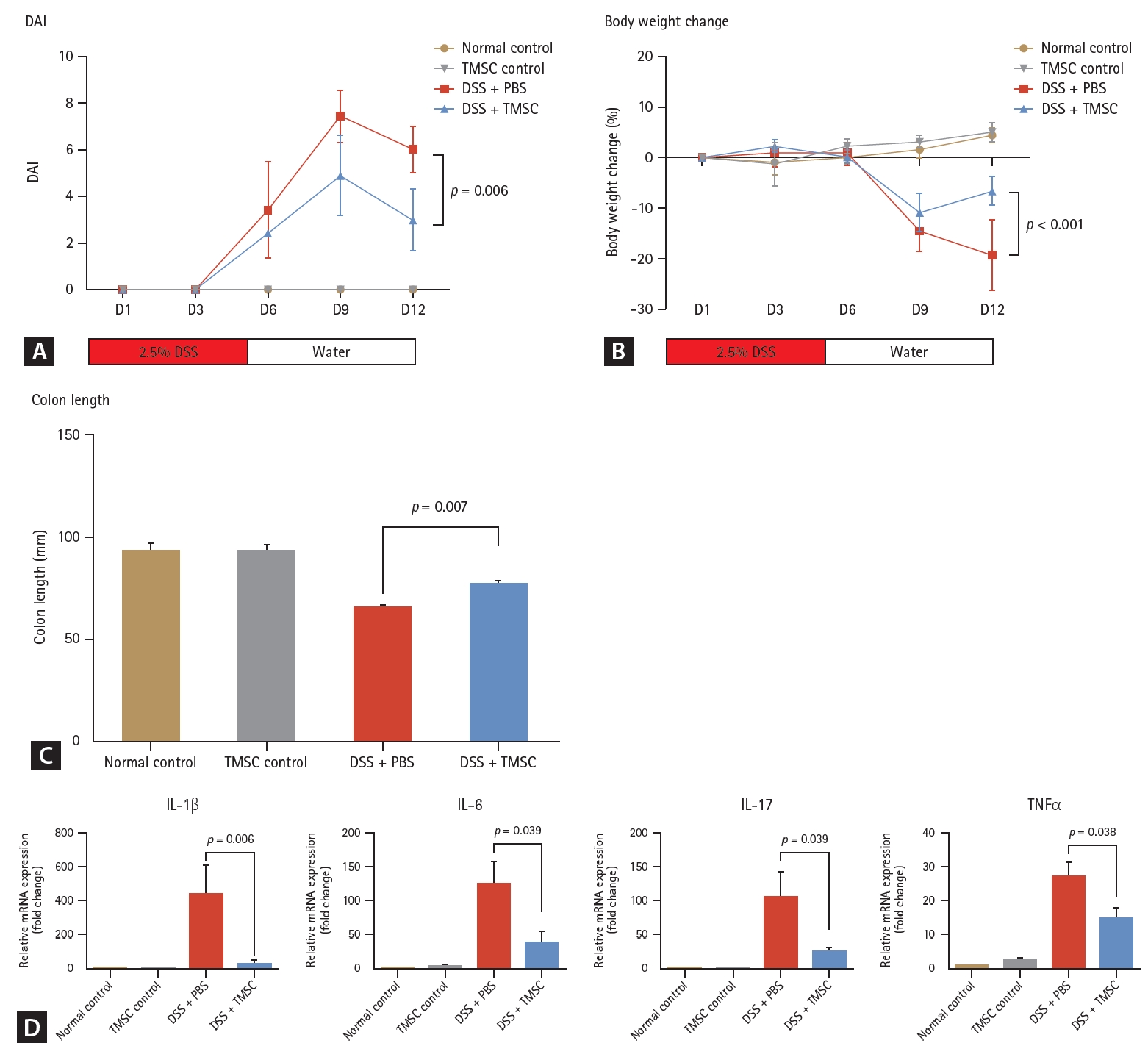

An acute mouse colitis model was established using 2.5% DSS for five days. In this model, PD-1 levels of colon tissues of acute colitis model were significantly increased compared to those of the normal or TMSC controls (1 vs. 8.92, p < 0.001 and 1.72 vs. 8.92, p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 4). However, the PD-L1 levels did not significantly change compared with those of the normal or TMSC controls (1 vs. 1.85, p = 0.295 and 1.28 vs. 1.85, p = 0.233, respectively) (Fig. 4). Treatment with TMSCs reversed colitis-associated colon length shortening in the acute DSS colitis model (66.0 ± 2.2 vs. 77.3 ± 3.1, p = 0.007) (Fig. 5C) and significantly improved macroscopic DAI based on rectal bleeding, stool consistency, and body weight loss (6.0 ± 1.0 vs. 3.0 ± 1.3, p = 0.006) (Fig. 5A). Additionally, body weight loss (%) in the TMSC-treated group was significantly lower than that in the DSS+PBS group (-19.2 ± 7.0 vs. -6.5 ± 2.8, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5B). Concurrently, with the amelioration of colitis symptoms, PD-1 levels were found to decrease significantly (8.92 vs. 4.70, p = 0.015) (Fig. 4A). Conversely, the PD-L1 levels were significantly increased compared to the colitis model (1.85 vs. 3.76, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4B).

Analysis of mRNA expression of other pro-inflammatory cytokines, the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, and TNFα were found to be significantly downregulated in the TMSC-treated group compared to the acute colitis group (p = 0.006, 0.039, 0.039, and 0.038, respectively) (Fig. 5D).

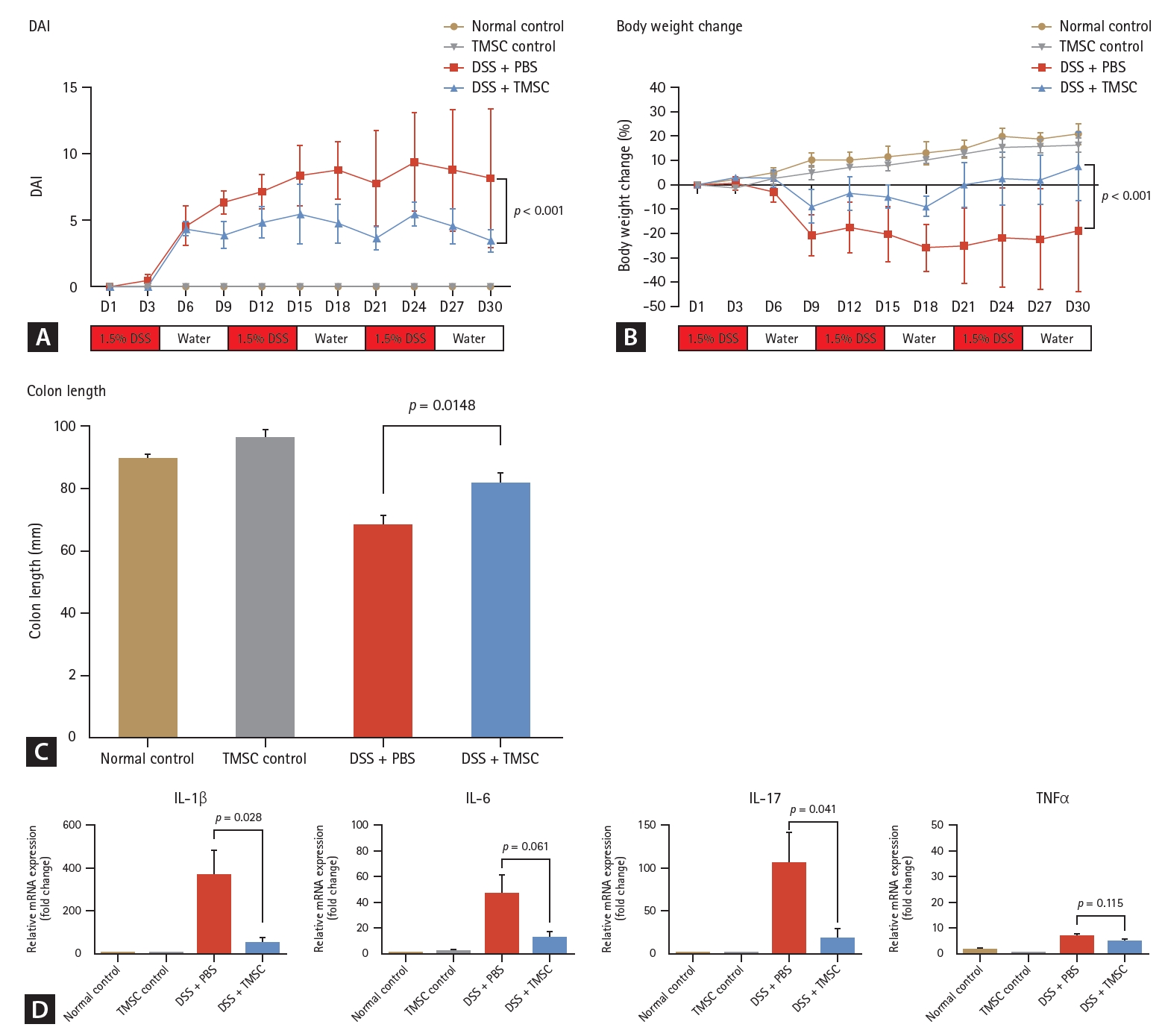

In the chronic colitis model, PD-1 levels were increased compared to the normal and TMSC controls (1 vs. 5.76, p = 0.037 and 1.13 vs. 5.76, p = 0.047, respectively). Conversely, PD-L1 levels were decreased compared to the normal controls (1 vs. 0.46, p = 0.040). Notably, PD-L1 levels sig-nificantly decreased in the TMSC control group compared with the normal control group (1 vs. 0.25, p < 0.001). After colitis induction using DSS, all DSS-treated mice exhibited persistent bloody diarrhea from day three. As shown in Figure 6A, the DAI in the TMSC-treated group was significantly lower than that in the DSS + PBS group at every time point (p < 0.001). The overall loss in body weight was significantly reduced in the TMSC-treated group compared to the DSS + PBS group (-18.8 ± 25.1 vs. 7.6 ± 14.0, p < 0.001) (Fig. 6B). Additionally, DSS-induced colon shortening was significantly reduced in the TMSC-treated group compared with the DSS + PBS group (68.0 ± 3.4 vs. 81.5 ± 2.9, p = 0.0148) (Fig. 6C). The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-17, were significantly decreased (p = 0.028 and 0.041, respectively) (Fig. 6D) in the TMSC-treated group compared to the DSS + PBS group. Furthermore, PD-1 and PD-L1 levels recovered after treatment with TMSCs. In the chronic colitis model, PD-L1 levels were significantly increased (0.46 ± 0.08 vs. 1.04 ± 0.77, p = 0.031) (Fig. 4D), while PD-1 levels decreased (5.76 ± 3.34 vs. 2.89 ± 0.65, p = 0.310) (Fig. 4C).

The roles of PD-1 and PD-L1 in the pathogenesis and disease course of IBD have not been fully evaluated. In our study, a decreased expression of PD-L1 was observed in the chronic colitis model, but not in the acute colitis model, suggesting a critical role of PD-L1 in persistent chronic inflammation in IBD. We also measured PD-1 and PD-L1 levels in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC. Levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 were significantly higher in patients with UC than in normal controls, and the expression of PD-1 was significantly higher in the mucosa with active inflammation than in those without active inflammation. Additionally, a decreased level of PD-L1 was associated with an extended disease phenotype in patients with UC. Our results showed that aberration of PD-L1 is associated with chronic inflammation and a more severe disease phenotype, highlighting its significance as a target for IBD in future treatments.

In our study, we observed significant increases in PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in the colonic mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. The results of previous studies examining the role of PD-1/PD-L1 in human IBD specimens are contradictory. In a study by Kanai et al. [7], the expressions of PD-1 and PD-L1, but not of PD-L2, in lamina propria mono-nuclear cells of IBD patients, including UC and CD, were significantly increased, suggesting the role of PD-1/PD-L1 interaction in the pathogenesis or regulation of IBD. In another study, the expressions of PD-L1 and PD-L2 were also reported to be higher in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC [18]. Nguyen et al. [19] also reported that the higher expression of PD-L1 in the resected intestinal mucosa of patients with UC and CD is associated with higher IBD activity and higher inflammatory infiltrates. Conversely, Beswick et al. [6] reported suppressed expression of PD-L1 in the colonic mucosa of patients with CD. Although the reason for this difference is unclear, it may be partially explained by the different disease phenotypes between patients with IBD and the different treatments that patients were receiving at the time of specimen acquisition. In our study, the level of PD-1 was significantly higher in colonic mucosa with active inflammation, and the level of PD-L1 was also numerically higher in inflamed colonic mucosa than in non-inflamed colonic mucosa, although the difference was not statistically significant. Therefore, active inflammation status at the time of sample collection may have affected the expression of PD-1 and PD-L1. Most previous studies, including ours, enrolled patients who were undergoing treatment for IBD rather than treatment-naïve patients. Their treatment may affect the levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC.

In this study, the expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 was measured not only in the human colonic mucosa but also in acute and chronic murine colitis models. As a result, levels of PD-1 were significantly increased in the acute and chronic colitis models, similar to those in the human colonic mucosa. The levels of PD-L1 expression varied between the acute and chronic models. PD-L1 expression was significantly decreased in the chronic colitis model, but not significantly changed in the acute colitis model. These results were contradictory with those of previous studies. In a study using chronic murine colitis model, the levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in T cells were reported to be significantly increased [7]. Conversely, Zhou et al. [20,21] found that the levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 expression significantly decreased in the intestinal tract of DSS-induced acute colitis model. The observed differences in PD-1 and PD-L1 levels in the murine colitis model are indicative of the involvement of this pathway in IBD pathogenesis. While inducing murine DSS-induced colitis, PD-1 knockout mice did not develop colon inflammation, suggesting that PD-1 may play an important role in the pathogenesis of IBD [6]. Additionally, Fc-conjugated PD-L1 showed a protective effect against DSS-induced and T-cell-induced colitis [22]. Our findings, together with previous findings, suggest that PD-L1 plays an important role in persistent chronic inflammation in IBD.

In both acute and chronic murine colitis models, PD-L1 levels increased significantly after TMSC treatment. Although these findings demonstrate the therapeutic efficacy of TMSCs in both acute and murine colitis, the precise mechanism underlying these treatment effects remains incompletely understood. In this regard, the secretion of soluble PD-L1 by TMSCs could play a key role in their therapeutic efficacy. Thus, TMSC-conditioned medium, as well as TMSCs, may exhibit therapeutic properties via these mechanisms, as suggested in a previous study [15]. In another, Kim et al. [5] found that TMSC-derived PD-L1 effectively suppressed Th17 differentiation and Th17-related immune responses. Given that the dysregulation of Th17 cells, along with Th17/Treg imbalance, plays a crucial role in mucosal inflammation associated with IBD, the regulation of Th17 by TMSCs could also play an important role in the treatment of murine colitis [23,24]. The levels of IL-17 were found to be significantly ameliorated after TMSC treatment in the murine colitis model in our study.

Also, PD-L1 level was significantly different according to the maximal disease extent in patients with UC. Other factors, including the clinical DAI and response to medications, were not significantly associated with PD-L1 levels. Notably, PD-L1 expression showed a stronger correlation with maximal disease extent than that with disease extent or active mucosal inflammation at the time of sample collection. The maximal disease extent is a well-known prognostic factor associated with disease outcomes in patients with UC. Although the reason for the different PD-L1 expression according to the maximal disease extent is unclear, the highly activated PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may inhibit disease progression and limit the disease extent of the colon in patients with UC. Therefore, patients with UC and higher colonic levels of PD-L1 have a lower probability of proximal disease progression. However, the level of PD-1 was not significantly associated with the maximal disease extent. This could be because PD-L1, which regulates the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway via its receptor, regardless of PD-1 level, is a factor related to the innate immune regulation property of patients. Conversely, level of PD-1 is more related to the active inflammatory status of the colonic mucosa rather than the immune response.

In conclusion, we found that the expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 was significantly increased in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC. The expression of PD-1 was associated with active inflammation in the colonic mucosa, and the expression of PD-L1 was associated with the maximal extent of disease in patients with UC; patients with UC having low PD-L1 levels had more extensive colitis. In the chronic colitis model, decreased level of PD-L1 was recovered due to the anti-inflammatory effect of TMSCs. Further, an improvement in colitis symptoms was observed. Thus, PD-L1 may have a possible role in the treatment of UC and could be a promising treatment target in patients with IBD, and further studies are needed to better understand how this target can be applied in real medical therapy.

1. The expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 was significantly increased in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC.

2. The expression of PD-1 was associated with active inflammation and patients with UC with the low PD-L1 levels had more extensive colitis.

3. In chronic murine colitis model, decreased levels of PD-L1 were recovered owing to the anti-inflammatory effect of TMSCs, suggesting a possible role in the treatment of UC.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Eun Mi Song: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing - original draft, funding acquisition; Yang Hee Joo: methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis; Sung-Ae Jung: conceptualization, resources, writing - review & editing, supervision; Ju-Ran Byeon: investigation, writing - review & editing; A-Reum Choe: methodology, investigation, writing - review & editing; Yehyun Park: investigation, writing - review & editing; Chung Hyun Tae: investigation, data curation, writing - review & editing; Chang Mo Moon: investigation, data curation, writing - review & editing; Seong-Eun Kim: investigation, data curation, writing - review & editing; Hye- Kyung Jung: investigation, data curation, writing - review & editing; Ki-Nam Shim: investigation, data curation, writing - review & editing

Funding

This study was supported by the Ewha Womans University College of Medicine Alumnae Association Research Foundation (EMARF), and partially by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of education (2020R1I1A1A01073545 to EMS, 2019R1A2C1002526 and 2022R1H1A2091616 to SAJ).

Figure 1.

The expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in the colonic mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. (A) The expression of PD-1 was significantly increased in the colonic mucosa of patients with UC compared to that of the normal controls. (B) The expression of PD-L1 was also significantly increased in patients with UC. (C, D) When compared the active inflammation in the mucosa, the expression of PD-1 was significantly higher in mucosa with active inflammation. However, the level of PD-L1 was not significantly different according to the mucosal inflammation. PD-1, programmed death 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Figure 2.

PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in the colonic mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis according to the maximal disease extent. (A) The levels of PD-1 did not significantly differ on the basis of the maximal disease extent. (B) When compared the maximal disease extent, the PD-L1 levels were highest in patients with proctitis (38.5 ± 46.7), followed by left-sided colitis (17.5 ± 23.1) and extensive colitis (5.2 ± 8.2) (p < 0.001). PD-1, programmed death 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1.

Figure 3.

PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in TMSCs. (A) The surface expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 increased after seven days of differentiation. (B) PD-L1 was expressed in the soluble medium of TMSCs (182.63 pg/mL) and the cell lysate of TMSCs (11.85 pg/protein). PD-1, programmed death 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; TMSC, tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cell.

Figure 4.

PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in acute and chronic mouse colitis models and changes after treatment with TMSCs. In the acute colitis model, PD-1 levels were significantly increased compared to the normal and TMSC controls (all p < 0.001). However, PD-L1 levels did not change significantly. After treatment with TMSCs, PD-1 levels were significantly decreased (A) and PD-L1 levels were significantly increased compared to those in the colitis model (B). In the chronic colitis model, PD-1 levels increased compared to those of the normal and TMSC controls (C). By contrast, PD-L1 levels were decreased compared to the normal contorls (D). After treatment with TMSCs, PD-L1 levels were significantly increased (D) while PD-1 levels were decreased (C) in the chronic colitis model. PD-1, programmed death 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; TMSC, tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cell; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Figure 5.

Treatment effect of TMSCs in the acute murine colitis model. (A) In the acute colitis model, the macroscopic DAI scores, based on rectal bleeding, stool consistency, and body weight loss, were significantly lower in the TMSC-treated group compared to the DSS + PBS group (p = 0.006). (B) Body weight loss (%) in the TMSC-treated group was significantly lower than that in the DSS + PBS group (-19.2 ± 7.0 vs. -6.5 ± 2.8; p < 0.001). (C) In the TMSC-treated group, colitis-associated colon length shortening in the acute DSS colitis model was recovered (66.0 ± 2.2 vs. 77.3 ± 3.1, p = 0.007). (D) mRNA expressions of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, and TNFα were significantly downregulated in the TMSC-treated group compared to the DSS + PBS group. DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TMSC, tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cell; DAI, disease activity index.

Figure 6.

Treatment effect of TMSCs in chronic murine colitis model. (A) In the chronic colitis model, the macroscopic DAI scores were significantly lower in the TMSC-treated group compared to the DSS + PBS group (p < 0.001). (B) Body weight loss (%) in the TMSC-treated group was significantly lower than in the DSS + PBS group (-18.8 ± 25.1 vs. 7.6 ± 14.0, p < 0.001). (C) In the TMSC-treated group, DSS-induced colon shortening was significantly decreased compared to the DSS+PBS group (68.0 ± 3.4 vs. 81.5 ± 2.9, p = 0.0148). (D) The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-17, were significantly decreased in the TMSC-treated group compared with the colitis control group (p = 0.028 and p = 0.041, respectively). DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TMSC, tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cell; DAI, disease activity index.

Table 1.

The primers sequences of the qRT-PCR in human and mouse colonic tissue

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients

REFERENCES

1. Mak WY, Zhao M, Ng SC, Burisch J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: east meets west. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;35:380–389.

2. Park SH, Kim YJ, Rhee KH, et al. A 30-year trend analysis in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district of Seoul, Korea in 1986-2015. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13:1410–1417.

3. Guan Q. A comprehensive review and update on the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol Res 2019;2019:7247238.

4. Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2008;26:677–704.

5. Kim JY, Park M, Kim YH, et al. Tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells (T-MSCs) prevent Th17-mediated autoimmune response via regulation of the programmed death-1/programmed death ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) pathway. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2018;12:e1022.

6. Beswick EJ, Grim C, Singh A, et al. Expression of programmed death-ligand 1 by human colonic CD90+ stromal cells differs between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease and determines their capacity to suppress Th1 cells. Front Immunol 2018;9:1125.

7. Kanai T, Totsuka T, Uraushihara K, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 suppresses the development of chronic intestinal inflammation. J Immunol 2003;171:4156–4163.

8. Scandiuzzi L, Ghosh K, Hofmeyer KA, et al. Tissue-expressed B7-H1 critically controls intestinal inflammation. Cell Rep 2014;6:625–632.

9. Park SJ, Kim JH, Song MY, Sung YC, Lee SW, Park Y. PD-1 deficiency protects experimental colitis via alteration of gut microbiota. BMB Rep 2017;50:578–583.

10. Flores AI, Gómez-Gómez GJ, Masedo-González Á, Martínez-Montiel MP. Stem cell therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a promising therapeutic strategy? World J Stem Cells 2015;7:343–351.

11. Ciccocioppo R, Bernardo ME, Sgarella A, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in the treatment of fistulising Crohn’s disease. Gut 2011;60:788–798.

12. Janjanin S, Djouad F, Shanti RM, et al. Human palatine tonsil: a new potential tissue source of multipotent mesenchymal progenitor cells. Arthritis Res Ther 2008;10:R83.

13. Oh SY, Choi YM, Kim HY, et al. Application of tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells in tissue regeneration: concise review. Stem Cells 2019;37:1252–1260.

14. Yu Y, Song EM, Lee KE, et al. Therapeutic potential of tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells in dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental murine colitis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0183141.

15. Lee KE, Jung SA, Joo YH, et al. The efficacy of conditioned medium released by tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a chronic murine colitis model. PLoS One 2019;14:e0225739.

16. Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006;8:315–317.

17. Yu Y, Park YS, Kim HS, et al. Characterization of long-term in vitro culture-related alterations of human tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells: role for CCN1 in replicative senescence-associated increase in osteogenic differentiation. J Anat 2014;225:510–518.

18. Rajabian Z, Kalani F, Taghiloo S, et al. Over-expression of immunosuppressive molecules, PD-L1 and PD-L2, in ulcerative colitis patients. Iran J Immunol 2019;16:62–70.

19. Nguyen J, Finkelman BS, Escobar D, Xue Y, Wolniak K, Pezhouh M. Overexpression of programmed death ligand 1 in refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Hum Pathol 2022;126:19–27.

20. Zhou L, Liu D, Xie Y, Yao X, Li Y. Bifidobacterium infantis induces protective colonic PD-L1 and Foxp3 regulatory T cells in an acute murine experimental model of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Liver 2019;13:430–439.

21. Zhou LY, Xie Y, Li Y. Bifidobacterium infantis regulates the programmed cell death 1 pathway and immune response in mice with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2022;28:3164–3176.

22. Song MY, Hong CP, Park SJ, et al. Protective effects of Fcfused PD-L1 on two different animal models of colitis. Gut 2015;64:260–271.

- TOOLS

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement figure 1

Supplement figure 1 Print

Print