|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 29(2); 2014 > Article |

|

To the Editor,

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The occurrence of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) as a secondary malignancy in patients diagnosed with DLBCL is extremely rare [1]. We report a unique case of secondary CML 10 years after chemotherapy and local irradiation for the treatment of tonsillar DLBCL. We also review the literature related to secondary CML.

A 40-year-old male with a sore throat and a right tonsillar mass was evaluated at a local clinic in September 2000. A biopsy revealed a malignant lymphoma (DLBCL). He was then transferred to our hospital, where a staging work-up was performed. There were no metastatic lesions except for the right tonsillar mass. There was also no marrow invasion or chromosomal abnormalities in his bone marrow. The patient had a stage IA DLBCL. He received six cycles of CHOP regimen (750 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide, 50 mg/m2 adriamycin, and 2 mg vincristine on day 1, and 100 mg prednisolone on days 1 to 5) chemotherapy every 3 weeks. Chemotherapy was followed by radiotherapy to the right tonsillar region (total, 25 Gy). A complete response was achieved and sustained for 10 years.

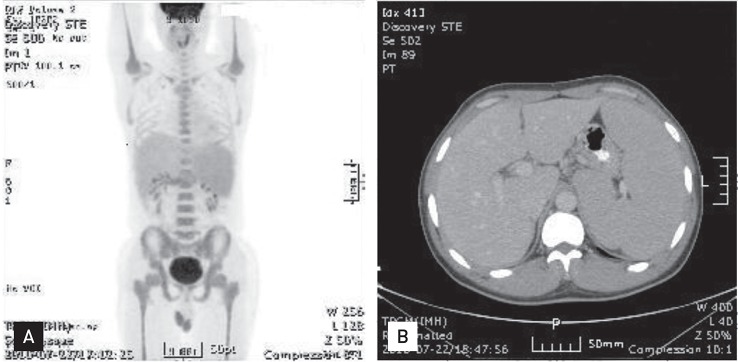

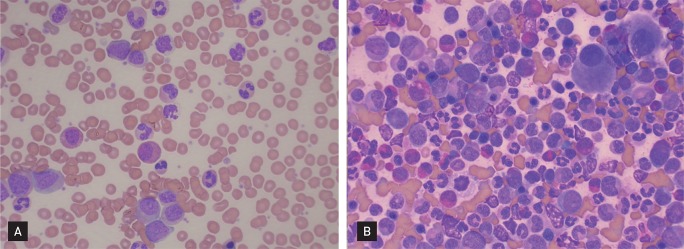

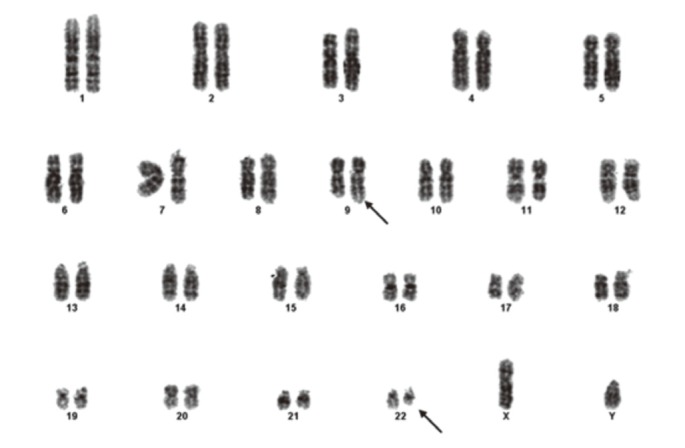

In July 2010, he sought evaluation at our hospital for easy fatigue and a febrile sensation of several months duration. His white blood cell count was 173,900/mm3, his hemoglobin concentration was 11.3 mg/dL, and platelet count was 735,000/mm3. Splenomegaly was noted on physical examination, but the remaining physical findings were nonspecific. Diffuse fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the bone marrow and mild and diffuse FDG uptake in the spleen were noted on a positron emission tomography and computerized tomography scan (Fig. 1). His platelet count was increased and a complete spectrum of granulocytic forms, from blasts to mature neutrophils, was noted on a peripheral blood smear (Fig. 2A). Hypercellular marrow with increased megakaryocytes and a markedly proliferated myeloid series were noted on a bone marrow study; however, the erythroid series was suppressed (Fig. 2B). A bone marrow chromosome analysis was then performed. Twelve cells were characterized by the presence of the Philadelphia translocation [t(9;22)(q34;q11)] in all analyzed mitoses; no other abnormalities were found (Fig. 3). PCR revealed a major BCR/ABL gene rearrangement in peripheral blood and bone marrow cells. The patient was diagnosed with CML.

He was treated with 400-mg/day imatinib beginning on 29 July 2010. After treatment for 1 month, his white blood cell count was 5,660/mm3, hemoglobin concentration was 10.9 mg/dL, and platelet count was 257,000/mm3 in the peripheral blood, which indicated a complete hematologic response. After treatment for 3 months, the CR/ABL gene rearrangement was not detected in peripheral blood and bone marrow cells, and the Philadelphia chromosome was not detected during a cytogenetic study of the bone marrow. Therefore, a complete cytogenetic response was obtained after 3 months of therapy with imatinib. He continued to be treated with 400-mg/day imatinib until March 2013, and the complete cytogenic response was maintained.

Secondary hematologic malignancies after neoplastic diseases are commonly reported as important late complications in cancer patients due to chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. Advances in the treatment of malignancies have been accompanied by an increased frequency of secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS); however, secondary CML is a rare event [2].

Recently, a relationship was reported between patients treated with cytotoxic therapy for malignancies and increased AML and MDS [3]. However, definitive evidence that the cytotoxic therapies used in cancer treatment increase the risk of CML has not been reported.

AML and MDS are genetically diverse, and numerous genetic abnormalities have been linked to their onset. In contrast, CML is homogeneous; the BCR-ABL oncogene is the single genetic lesion that results in the development of CML [3]. This suggests that the risk of CML after exposure to a chemical incitant is markedly lower than the risk of AML or MDS. A recent study reported that 40% of patients with therapy-related AML (tr-AML) and MDS received chemotherapy, 14% received radiation therapy, and 46% underwent a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy for a prior malignancy. Of the patients treated with chemotherapy, 78% received alkylating agents, and 39% received topoisomerase II inhibitors. The most common primary tumors of tr-AML and MDS were Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma [3]. In a similar study assessing patients with tr-CML, 44% of patients received combination therapy. In addition, the chemotherapy agents used to treat the primary disease included alkylating agents and topoisomerase II inhibitors. The most common primary tumor in this cohort of tr-CML patients was Hodgkin's lymphoma [1].

The occurrence of CML is increased in survivors of the atomic bomb detonations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and in patients irradiated for ankylosing spondylitis or cervical cancer [4,5], all of whom were exposed to high doses of ionizing radiation. This suggests that CML may be more likely to occur after acute high dose radiation exposure than other types of leukemia.

A previous study reported that the median interval to diagnosis of CML in patients treated with combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy, radiotherapy alone, and chemotherapy alone was 60 months (range, 27 to 240), 53 months (range, 27 to 109), and 35 months (range, 23 to 148), respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between these groups of patients [1]. In our study, the interval between diagnosis of DLBCL and CML was 118 months.

Our patient received six cycles of CHOP chemotherapy, including an alkylating agent, followed by local irradiation (total, 25 Gy) for the treatment of tonsillar DLBCL. However, the total dose of irradiation was low, and was divided into several fractions. In addition, there was a long interval to the diagnosis of CML (10 years). Therefore, it is unlikely that the treatment for DLBCL was related to the development of CML; however, tr-CML could not be excluded. Therefore, we were unable to discriminate between tr-CML and non-tr-CML in this patient. Nevertheless, chemotherapy or irradiation therapy for malignancies can cause tr-CML.

References

1. Aguiar RC. Therapy-related chronic myeloid leukemia: an epidemiological, clinical and pathogenetic appraisal. Leuk Lymphoma 1998;29:17ŌĆō26PMID : 9638972.

2. Kantarjian HM, Keating MJ, Walters RS, et al. Therapy-related leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome: clinical, cytogenetic, and prognostic features. J Clin Oncol 1986;4:1748ŌĆō1757PMID : 3783201.

3. Larson RA, Le Beau MM. Therapy-related myeloid leukaemia: a model for leukemogenesis in humans. Chem Biol Interact 2005;153-154:187ŌĆō195PMID : 15935816.

Figure┬Ā1

(A) Diffuse fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the bone marrow and mild and diffuse FDG uptake in the spleen with splenomegaly were noted on a positron emission tomography and computerized tomography (PET/CT) scan. (B) Abdominal CT revealed massive splenomegaly.

Figure┬Ā2

(A) Platelet counts were increased and a complete spectrum of granulocytic forms, from blasts to mature neutrophils, was noted on the peripheral blood smear (H&E, ├Ś400). (B) Hypercellular marrow with increased megakaryocytes and a markedly proliferated myeloid series was noted in the bone marrow; however, the erythroid series was suppressed (H&E, ├Ś400).

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print