To the Editor,

Drug-eluting stents (DESs) have revolutionized the treatment of coronary artery disease, as shown by the significant reductions in rates of repeat revascularization and major adverse cardiac events in randomized studies; however, concerns have been raised about the safety of these stents in relation to the occurrence of stent thrombosis [1].

Another area of debate regarding DES safety is related to hypersensitivity. Almost all of the hypersensitivity reactions reported to date have been seen in association with the standard adjunct drug therapy used with stent implantation. Nevertheless, on occasion, components of a DES, such as the metal stent backbone, the polymer coating, or the eluted drug, have been associated with hypersensitivity reactions in other settings [2].

To our knowledge, zotarolimuseluting stent (ZES)-induced hypersensitivity pneumonitis has not been reported previously. Here, we report a case of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, which was proven by lung biopsy and computed tomography, after coronary stenting using a ZES.

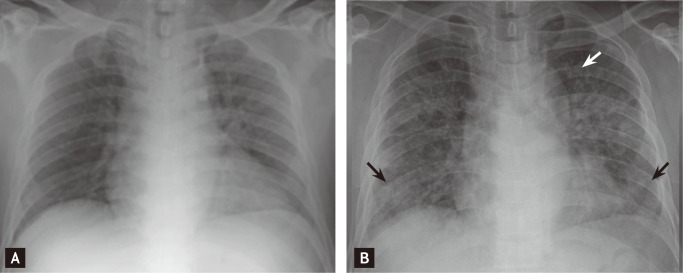

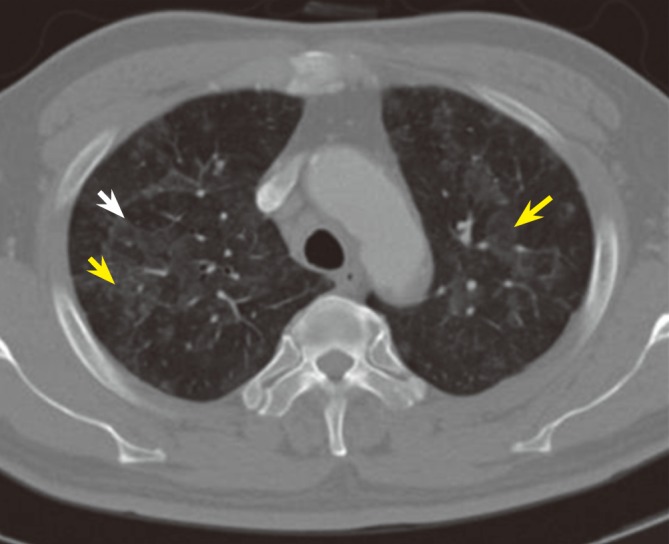

A 60-year-old man was admitted with resting chest pain. As a cardiovascular risk factor, he had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. He did not have any allergy history. Electrocardiography on admission showed T-wave inversion in the inferior leads. Diagnostic coronary angiography was performed due to his unstable clinical presentation. The results revealed significant stenosis in the mid-portion of the right coronary artery, and the patient underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. Aspirin (200 mg), clopidogrel (75 mg after a 300-mg loading dose), and carvedilol (12.5 mg) were prescribed for 2 days. Using standard angioplasty, a ZES (Endeavor, Medtronic, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) was implanted in the right coronary artery. There were no adverse events during the hospital stay. Thirteen days after the index procedure, the patient developed nonproductive cough, dyspnea, and malaise, and after 10 days with these symptoms, he returned to the hospital appearing acutely ill. On examination, he was febrile (39℃), had a respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute, and had an oxygen saturation of 94.9% while breathing room air. Fine inspiratory crepitations were audible on both lower lung fields. Chest X-rays showed perihilar peribronchial nodular opacities and diffuse ground-glass opacities in both lung fields as compared with the pre-procedural chest X-ray findings (Fig. 1). A complete blood analysis revealed a white blood cell count of 9,770/mm3, an eosinophil count of 780/mm3, and a hemoglobin level of 12.1 g/dL. The immunoglobulin E level was 242.0 IU/mL, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 56 mm in the first hour, and the C-reactive protein level was elevated to 71.9 mg/L. Empiric antibiotic therapy consisting of cefoxitin and roxithromycin was initiated to cover for community-acquired pneumonia. The patient continued to have intermittent fever, dry cough, and moderate dyspnea. On high-resolution computed tomography, diffuse ground-glass opacity and centrilobular nodules were observed throughout both lungs (Fig. 2). Open lung biopsy was performed to determine the cause of pneumonitis in this case, and it revealed diffuse involvement of chronic bronchiolar lesions with peribronchiolar fibrosis, inflammatory infiltration, and foci of luminal narrowing. There were a few areas of vague granulomas showing multinucleated giant cells around the bronchiolar lesions (Fig. 3A and 3B). The findings were therefore compatible with chronic bronchiolitis with peribronchiolar, probably hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Bacterial, viral, and fungal cultures from sputum and blood were negative. Serological test results were not consistent with acute infection caused by Mycoplasma species, and Legionella and Pneumococcus urinary antigens were negative. There was no evidence of infection on slides prepared for bacterial, fungal, or acid-fast organisms. Based on the biopsy results, the patient was treated with high-dose steroids for 2 weeks. Chest X-rays revealed improvement of the ground-glass appearance in both lung fields as compared with the previous films. The patient received steroid treatment with tapering for 2 months. Four months later, follow-up high-resolution computed tomography showed significant improvement of the hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The patient had no history of significant inhalational exposure. His medications, including clopidogrel, were not discontinued during management of the complication, and the pneumonitis did not recur. We concluded that the ZES could have caused the hypersensitivity pneumonitis. There were no adverse clinical events during the 10-month follow-up period.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is an allergic lung disease characterized by lymphocytic and granulomatous inflammation of the lung parenchyma and bronchioles caused by repeated exposure to a variety of etiological agents as well as genetic factors [3].

When considering the possibility of hypersensitivity pneumonitis after DES implantation, the essential first step in the differential diagnosis is a more detailed questioning about the patient's potential exposures. Local and systemic hypersensitivity manifestations can develop in response to implantation of DES in coronary arteries. The numerous potential antigens include not only many different complex organic particles from chemicals, including medications, but also stent components such as metal, polymer coating, or eluted drug [2].

The differential diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis is based on history, clinical features, laboratory and radiographic evidence, pulmonary function test results, and histological findings [3]. In the present case, the patient had no history of allergies. Symptoms, including cough and dyspnea, developed 2 weeks after stent implantation. The results of laboratory tests, including eosinophil count, immunoglobulin E level, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, were consistent with a hypersensitivity reaction. Chest radiography and high-resolution computed tomography showed a multifocal ground-glass appearance in both lung fields. Pulmonary function tests revealed a moderately restrictive ventilatory defect. Histological features on open lung biopsy were characteristic of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The patient's illness was unresponsive to standard broad-spectrum antibacterial treatment, but responded rapidly to steroid therapy. Based on the clinical course and pathological findings, a diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis was made in this case.

Compared with bare-metal stents, DESs-including the ZES used here-are safe and reduce the rates of clinical and angiographic restenosis. However, they may be a cause of systemic and intrastent hypersensitivity reactions. Respiratory hypersensitivity reactions may develop hours to weeks after DES insertion. There are three potential causal agents after DES insertion, i.e., anti-platelet agents, intravenous agents such as intravenous iodinated contrast agents used at implantation, and the DES itself [2]. In the present case, anti-platelet agents can be excluded as causal agents because the patient had previously taken anti-platelet agents without evidence of hypersensitivity. If the culprit were intravenous agents used at implantation, the reaction would have been expected to begin on the day of implantation and to resolve within 2 days; however, the patient showed evidence of a hypersensitivity reaction 13 days post-implantation. We concluded that DES was the most likely cause of the hypersensitivity response in this case.

Drugs used in other stents, including sirolimus and paclitaxel, can cause hypersensitivity pneumonitis [4,5]. Non-drug components of DES are also potential causes of hypersensitivity. The polymer coating can fragment and expose the metal struts, and nickel and molybdenum in the stainless steel may cause hypersensitivity [2]. Therefore, the hypersensitivity reaction in the present case could have been caused by zotarolimus, the polymer, or the metal struts.

This is the first report of a case of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in association with implantation of a ZES in a coronary artery. In summary, hypersensitivity pneumonitis is a rare complication of DES implantation. The diagnosis of ZES-induced hypersensitivity pneumonitis should be considered in patients who develop nonspecific respiratory symptoms and a diffuse bilateral interstitial pattern on chest radiography hours to weeks after insertion of a ZES.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print