INTRODUCTION

Ewing's sarcoma (ES) was first described as an osteolytic bone tumor composed of malignant, small round cells by James Ewing in 1921. Extraosseous Ewing's sarcoma was first described by Tefft in 1969 [1]; it is a rare, malignant mesenchymal tumor similar to intraosseous ES. Since its characterization in 1980s, this tumor has increasingly been reported from diverse sites including the oral cavity, salivary glands, subcutis, lung, heart, pericardium, biliary tract, kidney, urinary bladder, uterine corpus and cervix, gonads [2], pancreas, vagina, rectovaginal septum, prostate, esophagus, and stomach [3]. To the best of our knowledge, no reports of its occurrence in the lesser sac have been documented in the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 47-year-old woman presented with a short history of abdominal pain of 15 days duration. There was no history of vomiting, diarrhea, or weight loss. Physical examination revealed an epigastric mass measuring 7 ├Ś 8 cm, which was firm in consistency and moving with respiration. No organomegaly was noted. Hemoglobin was 11 g/dL. All other laboratory parameters were within normal limits.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed external indentation of the stomach. Computed tomography (CT) examination suggested a large, well-defined, heterogenously enhancing mass measuring 12 ├Ś 15 cm with an epicenter in the lesser sac and loss of fat planes with the body and part of the tail of the pancreas and posterior wall of stomach. Hypodense non-enhancing areas suggestive of necrosis or cystic change were observed. The possibility of an exophytic pancreatic mass or exophytic gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) from the posterolateral wall of the stomach was proposed (Fig. 1).

The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, which showed a tumor in the lesser sac abutting the left dome of the diaphragm dorsally, the splenic hilum to the left, the transverse mesocolon inferiorly, and the posterior wall of stomach anteriorly. The tumor extended posterior to the stomach and was firmly adherent to the pancreatic tissue. Excision of the tumor with a distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy was performed and the specimen was received in our laboratory for histopathological examination and diagnosis. A malignant pancreatic tumor was suspected clinically. No additional information, such as serum tumor markers, was available.

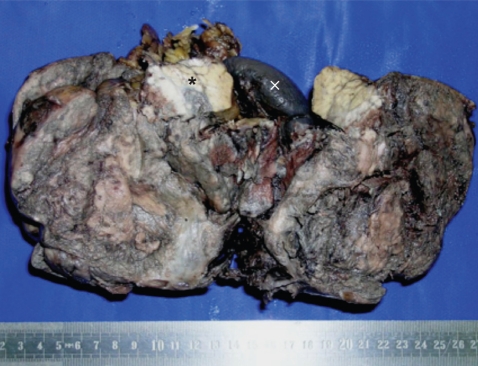

Grossly, the tumor was well-circumscribed, partly encapsulated, measured 10 ├Ś 15 cm, and weighed 830 g. The tail of the pancreas was compressed by the tumor and was identified near the splenic hilum. Cut section of the mass showed a grey tan hemorrhagic tumor with large areas of necrosis (corresponded to the cystic changes seen on CT) (Fig. 2).

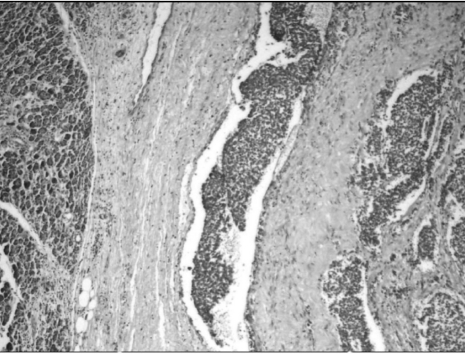

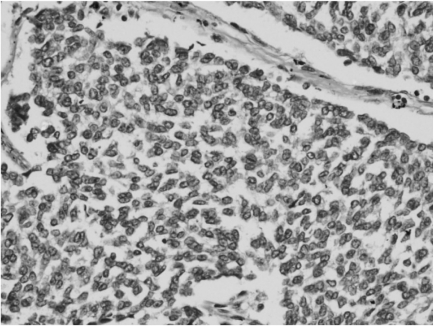

Microscopy revealed a fairly well-circumscribed tumor with a fibrous pseudocapsule composed of sheets of small round cells with enlarged round to oval nuclei, fine stippled chromatin, and moderately clear to amphophilic cytoplasm, which was periodic acid-Schiff stain positive. Geographic areas of necrosis with focal peritheliomatous proliferation of tumor cells around the blood vessels, increased mitosis, prominent apoptosis, and nuclear moulding were noted. In some areas, tumor islands were surrounded by desmoplastic stroma. Peripherally compressed pancreatic tissue was seen and no tumor infiltration was discerned (Figs. 3 and 4). The tumor cells were CD99 positive, while cytokeratin (CK), desmin, synaptophysin (SYP), and chromogranin (CHR) were negative (Fig. 5). Based on morphology and immunohistochemistry findings, a final diagnosis of extraosseous Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor (ES/PNET) of the lesser sac was made.

Metastatic workup of the patient was negative. She was scheduled for alternating IE (ifosfamide and etoposide) and VAC (vincristine, adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy. Currently, the patient has completed two cycles of chemotherapy with no further complaints and is receiving regular follow-up care.

DISCUSSION

ES and PNET are characterized by the same cytogenetic alterations (t(11;22) (q24;Q12) which forms EWSR1-FLI1 fusion product) [4] and comparable morphologic and immunophenotypic features. They are hence classified under the same group of lesions - the ES/PNET family of tumors [5]. In their extensive review on ectopic tumors, Wick and Nappi [2] attributed the origin of these tumors to ectopic neural and neuroectodermal proliferations. They further suggested that although neural tissues are ubiquitously distributed throughout the body, the occurrence of tumors related to this lineage is extremely uncommon in some topographic sites.

ES/PNET is a poorly differentiated tumor that is integrated in the morphologic category of 'small round cell' tumors [6]. The various entities that have 'small round cell' morphology occurring at this site are lymphoma, pancreatic endocrine tumor (PET), pancreatoblastoma, extra-renal Wilm's tumor, extra-adrenal neuroblastoma, hepatoblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT), and visceral small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNC). Extraosseous ES/PNET is rare and poses a diagnostic challenge to the pathologist. Specifically, there is a broad spectrum of tumors having a similar morphology that includes sheets of small, round blue cells. This problem is markedly enhanced when the tumor site of origin is uncertain, as observed in the present case.

Differential diagnoses of DSRCT, SCNC, PET, and pancreatoblastoma were entertained based on histomorphology in this case. DSRCT's are usually multicentric tumors involving the peritoneal cavity, although extraperitoneal neoplasms have been described [6]. The cellular phase does not have much desmoplasia and can resemble soft tissue ES. Since the tumor cells were negative for CK and desmin, DSRCT was ruled out. Cell to cell molding was noted in the present case, which is usually seen in SCNC. Since the cells were negative for SYP and CHR, small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and malignant PET were ruled out. Pancreatoblastomas are rare in adults and microscopically show islands of squamoid morules amongst the neoplastic cells [7], which was not observed in this case. Strong membrane positivity for CD99 was observed in all of the cells confirming the diagnosis of extraosseous ES/PNET.

Unlike intraosseous ES, the radiologic findings of extraosseous lesions are non-specific. In the present case, the tumor was mistaken for a pancreatic tumor or GIST with necrosis. This confusion may be partly due to the unanticipated occurrence of the tumor in a previously undescribed site.

In conclusion, extraosseus ES/PNETs are malignant, highly aggressive tumors, with a poor patient outcome. This report describes the first case of ES arising in the lesser sac. Even though it is rare, this entity should be considered in the differential diagnosis of intraabdominal, extraintestinal masses. A timely and accurate diagnosis can be obtained based on histomorphology combined with immunohistochemistry.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print