|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 26(4); 2011 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background/Aims

To determine whether female smokers are more or less susceptible to the detrimental pulmonary-function effects of smoking when compared to male smokers among patients with lung cancer.

Methods

Pack-years and pulmonary function indices were compared between 1,594 men and women with lung cancer ifferences in individual susceptibility to smoking were estimated using a susceptibility index formula.

Results

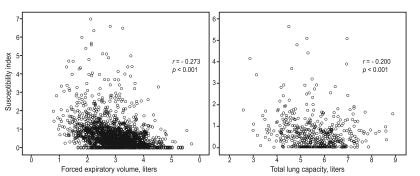

Of the patients, 959 (92.8%) men and 74 (7.2%) women were current smokers. Common histological types of lung cancer were squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and small cell carcinoma, among others. Women had a lower number of pack-years, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1, liters), forced vital capacity (FVC, liters), and total lung capacity (TLC, liters) compared to those of men (25.0 ┬▒ 19.2 vs. 42.9 ┬▒ 21.7 for pack-years; 1.4 ┬▒ 0.5 vs. 2.0 ┬▒ 0.6 for FEV1; 3.0 ┬▒ 0.7 vs. 2.0 ┬▒ 0.6 for FVC; 4.5 ┬▒ 0.8 vs. 5.7 ┬▒ 1.0 for TLC; all p < 0.001). The susceptibility index for women was significantly higher compared to that of men (1.1 ┬▒ 4.1 vs. 0.7 ┬▒ 1.1; p = 0.001). A significant inverse association was shown between the susceptibility index and TLC and FVC (r = -0.200 for TLC, -0.273 for FVC; all p < 0.001).

Lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which are two distinct phenotypes, are highly likely to be attributable to smoking. To date, these two diseases are understood as a single continuum or a different outcome from the same insult [1]. The potential interaction of gender with the effects of smoking on the development of these diseases is a major clinical issue but one that is not well established. Pulmonary function is one of the most useful indicators for estimating the hazardous effects of smoking on the lungs [2].

Many studies had been conducted to verify whether the harmful effects of smoking on pulmonary function differ according to gender [3-12]. These studies were conducted on healthy populations or patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and showed inconsistent results. Although the effects of smoking on carcinogenesis between men and women have been reported with mixed results in cohort and case-control studies, the effect of smoking on pulmonary function in patients with lung cancer according to gender has not been examined [13-16].

Therefore, we conducted this study to investigate if susceptibility to smoking was different between men and women in a hospital-based lung cancer cohort.

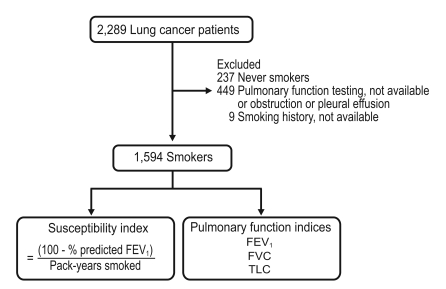

Of approximately 2,300 patients with lung cancer who were diagnosed between 2001 and 2009 at the Lung Cancer Cohort of Inha University Hospital (Incheon, Korea) [17], all consecutive patients who were smokers or had a history of smoking and who took a pulmonary function test at diagnosis were initially considered for this study (Fig. 1). Information including body mass index, histological type, and smoking habits was obtained from a data system. Patients with obstruction of the trachea or a lobar bronchus and significant pleural effusion were excluded, because these factors can potentially affect the results of pulmonary function testing.

Pulmonary function testing was performed by a certified technician following the American Thoracic Society recommendations [18]. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1, liters or percentage), forced vital capacity (FVC, liters or percentage), and total lung capacity (TLC, liters or percentage) were estimated. Data on smoking habits were prospectively collected by a well trained research nurse who interviewed patients and asked "Have you ever smoked?", and "Do you smoke now?" Pack-years smoked were calculated by asking, "How many cigarettes do you smoke per day on average?" and "How long did you smoke?"

We evaluated the susceptibility index (SI) to quantify the decrease in individual pulmonary function with a susceptibility index formula: [100 - % FEV1] / pack-years [9]. This formula assumes that each patient's baseline FEV1 would be normal (100% of predicted) without the hazardous effects of smoking. The SI was defined as the loss of pulmonary function (measured in % predicted FEV1) per pack-year smoked.

Differences in clinical variables between men and women were compared using the Žć2 test for categorical variables and the independent t test for continuous variables. Correlations between the SI and pulmonary function were evaluated with Pearson's Žć2 test. All statistical testing was performed at the two-sided 0.05 level. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

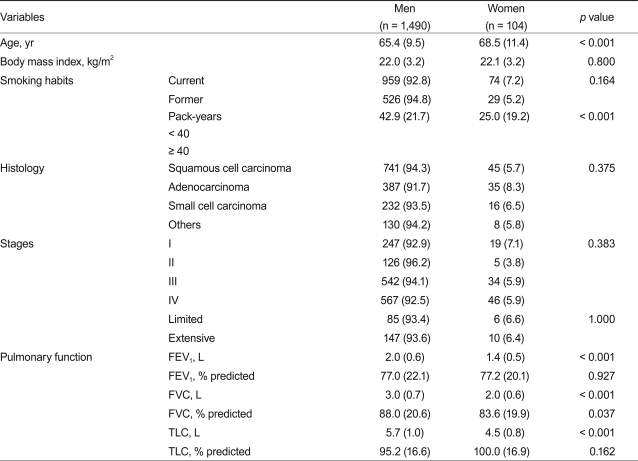

Table 1 shows the distribution of clinical characteristics by gender in the 1,594 patients. Patients consisted of 1,490 men (959 current-smokers, 526 former-smokers) and 104 women (74 current-smokers, 29 former-smokers). Ages ranged from 28 to 89 years (median, 67). Pack-years smoked in women were significantly lower than those of men (p < 0.001). No differences in body mass index or distribution of histological types or stage were found between men and women.

Women had significantly lower estimates of FEV1, FVC, and TLC compared to those of men (2.0 vs. 1.4, 3.0 vs. 2.0, 5.7 vs. 4.5, respectively; all p < 0.001). The SI estimates in women were significantly higher compared to those in men (1.1 vs. 0.7% per pack-years; p = 0.001) (Fig. 2). The SI estimate showed a significant inverse relationship with liters of FVC or TLC (r = -0.273, p < 0.001 for FVC; r = -0.200, p < 0.001 for TLC) (Fig. 3). The SI estimates also showed a significant relationship with FVC based on gender (r = -0.331, p < 0.001 for men; r = -0.380, p < 0.001 for women) and TLC (r = -0.143, p = 0.002 for men; r = - 0.277, p = 0.053 for women, data not shown).

This study demonstrated, for the first time, that pulmonary function in female patients with lung cancer may be more susceptible to the hazardous effects of smoking than that of men. The higher susceptibility of women, who showed a significantly lower amount of smoking compared to men, originated from their lower lung volume.

It has been a controversial issue as to whether a gender difference is present regarding the detrimental effects of smoking on pulmonary function [3-12]. Our results were similar to some previous cross-sectional or longitudinally designed studies conducted in an otherwise healthy population or in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [3,7-9]. However, to directly compare results of studies with different designs or subjects is a matter for concern because of epidemiological biases, such as a healthy smoking effect or a different prevalence of smokers, originating from the heterogeneity of the population, and the existence of individual variation regarding the harmful effects of smoking on pulmonary function. Unlike previous series, this study was conducted among patients with lung cancer who came from a hospital-based cohort. All subjects in this study were expected to have lung cancer due to smoking and, thus, were likely to have homogenous characteristics in terms of the hazardous effects of smoking.

In this study, we used the SI to evaluate susceptibility. This index was originally designed to quantify a decrease in FEV1 as a result of pack-years smoked in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Although women presented with significantly fewer pack-years, compared to those of men, the SI was significantly higher in women, as compared to that in men (0.7 vs. 1.1; p = 0.001). Dransfield et al. [9] reported that the SIs of men and women are 0.9 and 1.1, respectively, for Caucasians and 1.2 and 1.4, respectively, for African-American patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Considering similar SI estimates and different amounts smoked between these Caucasian and African-American women (40-45 pack-years) and Korean female patients with lung cancer (25 pack-years) in this study, it could be postulated that an ethnic difference may have modulated the deleterious ef fects. Our results showed a signif icant inverse relationship between SI and FVC and TLC, indicating that higher susceptibility in women might be attributed to their lower lung volume. It could be postulated that the more harmful effects of smoking could be expected after a given amount smoked in patients with a smaller lung volume.

The present study had some limitations. First, we did not collect detailed information on smoking habits such as brand name or depth of inhalation, which could affect pulmonary function [5]. Second, the number of female smokers with lung cancer in this study could be too small to compare variables by gender, given that the incidence of female smokers in South Korea is approximately 2%, which is much lower than that of other countries. Third, a serial estimate of the annual decline in pulmonary function is the most valuable method to assess the harmful effects of smoking. Alternatively, we estimated the effect using the SI, which assesses loss of pulmonary function per pack-years smoked.

Nevertheless, our results suggest that female smokers with lung cancer are more susceptible to the hazardous effects of smoking, as compared to men.

References

1. Petty TL. Are COPD and lung cancer two manifestations of the same disease? Chest 2005;128:1895ŌĆō1897PMID : 16236829.

2. Cohen BH. Is pulmonary dysfunction the common denominator for the multiple effects of cigarette smoking? Lancet 1978;2:1024ŌĆō1027PMID : 82037.

3. Xu X, Li B, Wang L. Gender difference in smoking effects on adult pulmonary function. Eur Respir J 1994;7:477ŌĆō483PMID : 8013605.

4. van Pelt W, Borsboom GJ, Rijcken B, Schouten JP, van Zomeren BC, Quanjer PH. Discrepancies between longitudinal and cross-sectional change in ventilator function in 12 years of follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149:1218ŌĆō1226PMID : 8173762.

5. Lange P, Groth S, Nyboe J, et al. Decline of the lung function related to the type of tobacco smoked and inhalation. Thorax 1990;45:22ŌĆō26PMID : 2321172.

6. Vollmer WM, Enright PL, Pedula KL, et al. Race and gender differences in the effects of smoking on lung function. Chest 2000;117:764ŌĆō772PMID : 10713004.

7. Chen Y, Horne SL, Dosman JA. Increased susceptibility to lung dysfunction in female smokers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;143:1224ŌĆō1230PMID : 2048804.

8. Burrows B, Knudson RJ, Cline MG, Lebowitz MD. Quantitative relationships between cigarette smoking and ventilatory function. Am Rev Respir Dis 1977;115:195ŌĆō205PMID : 842934.

9. Dransfield MT, Davis JJ, Gerald LB, Bailey WC. Racial and gender differences in susceptibility to tobacco smoke among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2006;100:1110ŌĆō1116PMID : 16236491.

10. Langhammer A, Johnsen R, Gulsvik A, Holmen TL, Bjermer L. Sex differences in lung vulnerability to tobacco smoking. Eur Respir J 2003;21:1017ŌĆō1023PMID : 12797498.

11. Tashkin DP, Clark VA, Coulson AH, et al. The UCLA population studies of chronic obstructive respiratory disease. VIII. Effects of smoking cessation on lung function: a prospective study of a free-living population. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984;130:707ŌĆō715PMID : 6497153.

12. Viegi G, Paoletti P, Prediletto R, et al. Prevalence of respiratory symptoms in an unpolluted area of northern Italy. Eur Respir J 1988;1:311ŌĆō318PMID : 3260872.

13. International Early Lung Cancer Action Program Investigators. Henschke CI, Yip R, Miettinen OS. Women's susceptibility to tobacco carcinogens and survival after diagnosis of lung cancer. JAMA 2006;296:180ŌĆō184PMID : 16835423.

14. Bain C, Feskanich D, Speizer FE, et al. Lung cancer rates in men and women with comparable histories of smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:826ŌĆō834PMID : 15173266.

15. Risch HA, Howe GR, Jain M, Burch JD, Holowaty EJ, Miller AB. Are female smokers at higher risk for lung cancer than male smokers? A case-control analysis by histologic type. Am J Epidemiol 1993;138:281ŌĆō293PMID : 8395141.

16. Freedman ND, Leitzmann MF, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Abnet CC. Cigarette smoking and subsequent risk of lung cancer in men and women: analysis of a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:649ŌĆō656PMID : 18556244.

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

Gender and age differences in obesity among Korean adults2013 January;28(1)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print