|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 25(4); 2010 > Article |

|

Abstract

A 63-year-old female was admitted to our hospital with a tender abdominal wall mass about 15 cm in diameter, which she had for 1 month. About 1 week earlier, the patient had also perceived a mass in the neck area. Computed tomography revealed huge thyroid and periumbilical masses. The thyroid hormone levels were consistent with a hyperthyroid state. Pathological examination of the thyroid mass was compatible with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) and the abdominal cutaneous mass was shown to be metastatic ATC. Despite palliative radiotherapy and chemotherapy, the patient died of respiratory failure on her 63rd day of hospitalization. This case demonstrates that abdominal cutaneous metastasis and hyperthyroidism can occur as initial manifestations of ATC. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case.

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) is one of the most aggressive endocrine tumors and has a poor prognosis with a median survival of 4 to 12 months from the time of diagnosis [1,2]. Fortunately, it accounts for only 1 to 2% of all thyroid cancer [3]. The mean age at diagnosis is 55 to 65 years [1,2]. Systemic metastases occur in up to 75% of patients during their illness, most commonly in the lungs in up to 80% of cases, followed by bone in 6-15% and the brain in 5-13% [4]. Skin metastases from thyroid carcinoma are extremely rare and usually occur in the setting of disseminated neoplastic disease [5]. Furthermore, primary thyroid malignancies typically do not interfere with thyroid function and the presentation of ATC with hyperthyroidism is extremely rare. Several case reports on subjects with ATC and hyperthyroidism have been published [6-15]. Here, we describe a rare case that presented with abdominal cutaneous metastasis from ATC, concurrent with the development of hyperthyroidism.

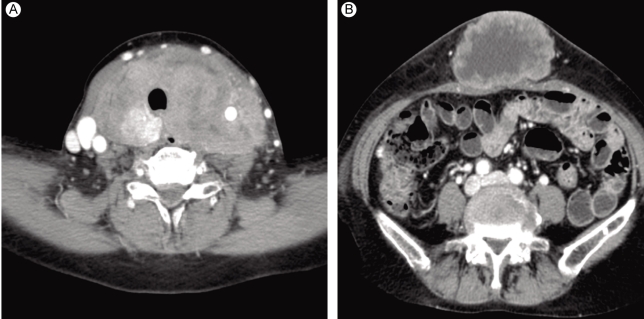

A 63-year-old female was admitted to our hospital for the evaluation of a huge abdominal mass. One month earlier, when the patient first perceived the abdominal mass, it measured about 2 cm. Recently, a neck mass also increased rapidly in size, with accompanying dysphagia, shortness of breath, and hoarseness. She had no history of goiter. On physical examination, she had a resting tachycardia with a pulse rate of 100-110 per minute. The abdominal mass was about 15 cm in diameter (Fig. 1A). A huge, firm neck mass occupied both lobes of the thyroid, with palpable lymph nodes on the left (Fig. 1B). She also had a 3-cm skin nodule on her right thigh that was hard and non-tender (Fig. 1C). Computed tomography (CT) revealed huge thyroid (Fig. 2A) and periumbilical (Fig. 2B) masses, infiltrating adjacent tissues. The abdominal mass was based primarily in the subcutaneous fat layer. A pulmonary mass, suggestive of metastasis, was also detected by CT. There was no definite evidence of bone metastasis on a bone scan. The initial thyroid function tests were consistent with a hyperthyroid state: thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) < 0.11 mU/L (normal range, 0.4 to 4.1); free T4 (fT4) 3.34 ng/dL (normal range, 0.70 to 1.80); thyroglobulin 171.8 ng/mL (normal range, 0 to 40); and thyroglobulin antibody 85 U/mL (normal range, 0 to 100 U/mL). Anti-thyroglobulin antibody, anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody, and serum calcitonin were all normal.

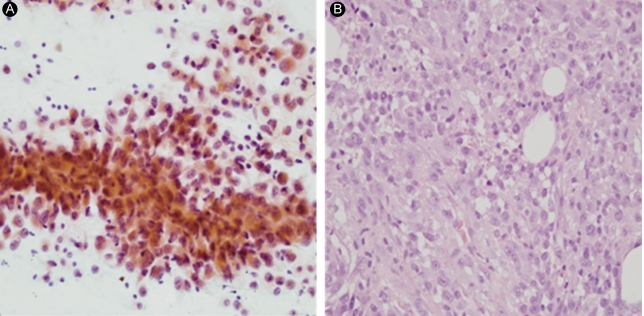

Fine needle aspiration of the thyroid mass revealed many large, pleomorphic, epithelioid cells forming loose clusters and was compatible with anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid (Fig. 3A). The histological features of the excised periumbilical mass were similar to those in the thyroid and the lesion was diagnosed as metastatic ACT (Fig. 3B). Immunohistochemical staining of the abdominal wall mass was positive for cytokeratin-7 and negative for cytokeratin-20, thyroid transcription factor-1, and thyroglobulin.

After the diagnosis of ATC was made, palliative radiotherapy to the neck area was initiated on the 15th day of hospitalization, to relieve local symptoms associated with the thyroid mass. Although this patient had asymptomatic hyperthyroidism, she was given propylthiouracil preemptively because of the possibility of radiotherapy-induced thyrotoxicosis. During radiotherapy, the thyroid function tests were repeated on the 24th day and the fT4 and TSH levels were 3.09 ng/dL and < 0.05 mU/L, respectively. However, she had no thyrotoxic symptoms except tachycardia. The dyspnea was improved after the completion of radiotherapy (35 Gy/14 fractions) and systemic chemotherapy (paclitaxel) was administered on the 36th day. However, the tumor had an aggressive course despite chemotherapy. The patient developed vocal cord paralysis with severe airway compromise and died of respiratory distress on her 63rd day of hospitalization.

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is one of the most lethal solid tumors in humans. It aggressively invades adjacent tissues and frequently metastasizes to distant organs via the bloodstream. Distant metastases of ATC are usually localized in the lung, bone, and brain [4]. Cutaneous metastasis of thyroid cancer is very rare. The frequency of skin metastasis varies with the histological type of thyroid cancer. Dahl et al. [5] reviewed the English literature from 1964 onwards and found 43 cases of thyroid carcinoma with skin metastases. They found that papillary carcinoma was the most common thyroid cancer to result in skin metastases, representing 41% of the cases, followed by follicular carcinoma at 28%, with anaplastic carcinoma and medullary carcinoma each constituting 15% of the cases. By contrast, Koller et al. [16] reported that follicular carcinoma has a greater preponderance for cutaneous metastases than papillary carcinoma. Common cutaneous metastatic sites for the thyroid carcinoma are the scalp and neck [17,18]. However, cutaneous metastasis from ATC as the initial presentation is extremely rare and abdominal wall metastasis of ATC has not been reported.

A clinical presentation with hyperthyroidism is also rare in ATC. Sekiguchi et al. [19] studied the biological characteristics and chemosensitivity profiles in four human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell lines and found that all of four cell lines lost their differentiated function and were unable to synthesize thyroid hormone. Consequently, primary thyroid cancers typically do not interfere with thyroid function. The proposed mechanism for thyrotoxicosis is invasion and destruction of the normal thyroid parenchyma by the tumor, resulting in an excessive release of pre-formed thyroid hormone into the circulation. As this clinical presentation is analogous to various forms of thyroiditis, Rosen et al. [20] called this condition 'malignant pseudothyroiditis'. Subsequently, a few case reports of ATC patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic hyperthyroidism have been published [6-15]. Although the thyroid function tests revealed overt hyperthyroidism, our patient had no definite symptoms or signs of thyrotoxicosis.

Survival after the diagnosis of ATC is extremely poor. Since more than half of ATC patients have metastatic disease at presentation, the importance of chemotherapy in the management of ATC cannot be understated. However, the outcomes of chemotherapy have been very disappointing. Although doxorubicin is the drug used most commonly, it has a response rate of less than 22% and plays limited roles in the treatment of ATC [21]. In one phase II clinical study, paclitaxel showed promising results and had a 53% response rate [22]. However, this potential role of paclitaxel needs to be evaluated further, and our patient did not benefit from paclitaxel chemotherapy.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates that an abdominal cutaneous metastatic mass and hyperthyroidism can occur as manifestations of ATC. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of ATC initially presenting with cutaneous metastasis in the abdominal wall, concurrent with hyperthyroidism. Further efforts to improve the treatment results for ATC patients are needed.

References

1. Venkatesh YS, Ordonez NG, Schultz PN, Hickey RC, Goepfert H, Samaan NA. Anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid: a clinicopathologic study of 121 cases. Cancer 1990;66:321ŌĆō330PMID : 1695118.

2. Tan RK, Finley RK 3rd, Driscoll D, Bakamjian V, Hicks WL Jr, Shedd DP. Anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid: a 24-year experience. Head Neck 1995;17:41ŌĆō47PMID : 7883548.

3. Gilliland FD, Hunt WC, Morris DM, Key CR. Prognostic factors for thyroid carcinoma: a population-based study of 15,698 cases from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program 1973-1991. Cancer 1997;79:564ŌĆō573PMID : 9028369.

4. McIver B, Hay ID, Giuffrida DF, et al. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: a 50-year experience at a single institution. Surgery 2001;130:1028ŌĆō1034PMID : 11742333.

5. Dahl PR, Brodland DG, Goellner JR, Hay ID. Thyroid carcinoma metastatic to the skin: a cutaneous manifestation of a widely disseminated malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;36:531ŌĆō537PMID : 9092737.

6. Mangla JC, Rastogi GK, Pathak IC. Anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid complicating severe thyrotoxicosis. J Indian Med Assoc 1967;49:286. PMID : 5594025.

7. Alagol F, Tanakol R, Boztepe H, Kapran Y, Terzioglu T, Dizdaroglu F. Anaplastic thyroid cancer with transient thyrotoxicosis: case report and literature review. Thyroid 1999;9:1029ŌĆō1032PMID : 10560959.

8. Oppenheim A, Miller M, Anderson GH Jr, Davis B, Slagle T. Anaplastic thyroid cancer presenting with hyperthyroidism. Am J Med 1983;75:702ŌĆō704PMID : 6624779.

9. Murakami T, Noguchi S, Murakami N, Tajiri J, Ohta Y. Destructive thyrotoxicosis in a patient with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Endocrinol Jpn 1989;36:905ŌĆō907PMID : 2633916.

10. Basaria S, Udelsman R, Tejedor-Sojo J, Westra WH, Krasner AS. Anaplastic pseudothyroiditis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;56:553ŌĆō555PMID : 11966749.

11. Villa ML, Mukherjee JJ, Tran NQ, Cheah WK, Howe HS, Lee KO. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma with destructive thyrotoxicosis in a patient with preexisting multinodular goiter. Thyroid 2004;14:227ŌĆō230PMID : 15072705.

12. Kumar V, Blanchon B, Gu X, Fowler M, Scarborough D, Nathan CO, Yaturu S. Anaplastic thyroid cancer and hyperthyroidism. Endocr Pathol 2005;16:245ŌĆō250PMID : 16299408.

13. Lee HG, Yum MK. Fourier analysis of doppler arterial waveforms of lower extremity. J Korean Soc Vasc Surg 2001;17:56ŌĆō62.

14. Kim HY, Chung KW, Kim HW, Youn YK, Oh SK. Clinical analysis of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. J Korean Surg Soc 2001;61:142ŌĆō147.

15. Phillips JS, Pledger DR, Hilger AW. Rapid thyrotoxicosis in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. J Laryngol Otol 2007;121:695ŌĆō697PMID : 17156585.

16. Koller EA, Tourtelot JB, Pak HS, Cobb MW, Moad JC, Flynn EA. Papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma metastatic to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. Thyroid 1998;8:1045ŌĆō1050PMID : 9848721.

17. Alwaheeb S, Ghazarian D, Boerner SL, Asa SL. Cutaneous manifestations of thyroid cancer: a report of four cases and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol 2004;57:435ŌĆō438PMID : 15047753.

18. Quinn TR, Duncan LM, Zembowicz A, Faquin WC. Cutaneous metastases of follicular thyroid carcinoma: a report of four cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol 2005;27:306ŌĆō312PMID : 16121050.

19. Sekiguchi M, Shiroko Y, Arai T, et al. Biological characteristics and chemosensitivity profile of four human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell lines. Biomed Pharmacother 2001;55:466ŌĆō474PMID : 11686581.

20. Rosen IB, Strawbridge HG, Walfish PG, Bain J. Malignant pseudothyroiditis: a new clinical entity. Am J Surg 1978;136:445ŌĆō449PMID : 707723.

Figure┬Ā1

A periumbilical mass about 15 cm in diameter (A), thyroid mass (B), and another skin lesion on the right thigh (C) were detected at the initial physical examination.

Figure┬Ā2

Computed tomography revealed a huge thyroid mass (A) and a cutaneous mass in the umbilical area (B).

Figure┬Ā3

(A) Fine needle aspiration of the thyroid mass. The tumor is present as loose clusters or single cells and is composed of epithelioid cells with pleomorphic nuclei (Papanicolaou, ├Ś 400). (B) Excisional biopsy specimen from the periumbilical area. The tumor is composed of pleomorphic, epithelioid, and spindle cells with frequent mitotic figures (H&E, ├Ś 400).

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print