Current perspectives on interstitial lung abnormalities

Article information

Abstract

Interstitial lung abnormalities (ILAs) are early indicators of interstitial lung disease, often identified incidentally via computed tomography of the chest. This review explores the diagnostic criteria for ILAs as outlined by the Fleischner Society, highlights associated risk factors, examines their impact on patient outcomes, and discusses management strategies. The prevalence of ILAs varies significantly, ranging from 3% to 17% across populations. Key risk factors include advanced age, smoking status, and underlying genetic predispositions. Recent advancements in imaging analysis, particularly through automated quantitative systems, have enhanced the accuracy of ILA detection. Although often subtle in presentation, ILAs hold clinical significance due to their associations with impaired lung function, progressive fibrosis, and increased mortality. Therefore, monitoring and management plans should be individualized to the risk profile of patients. Further studies are needed to refine ILA diagnostic criteria, enhance our understanding of their clinical implications, and establish optimal timing for therapeutic interventions.

INTRODUCTION

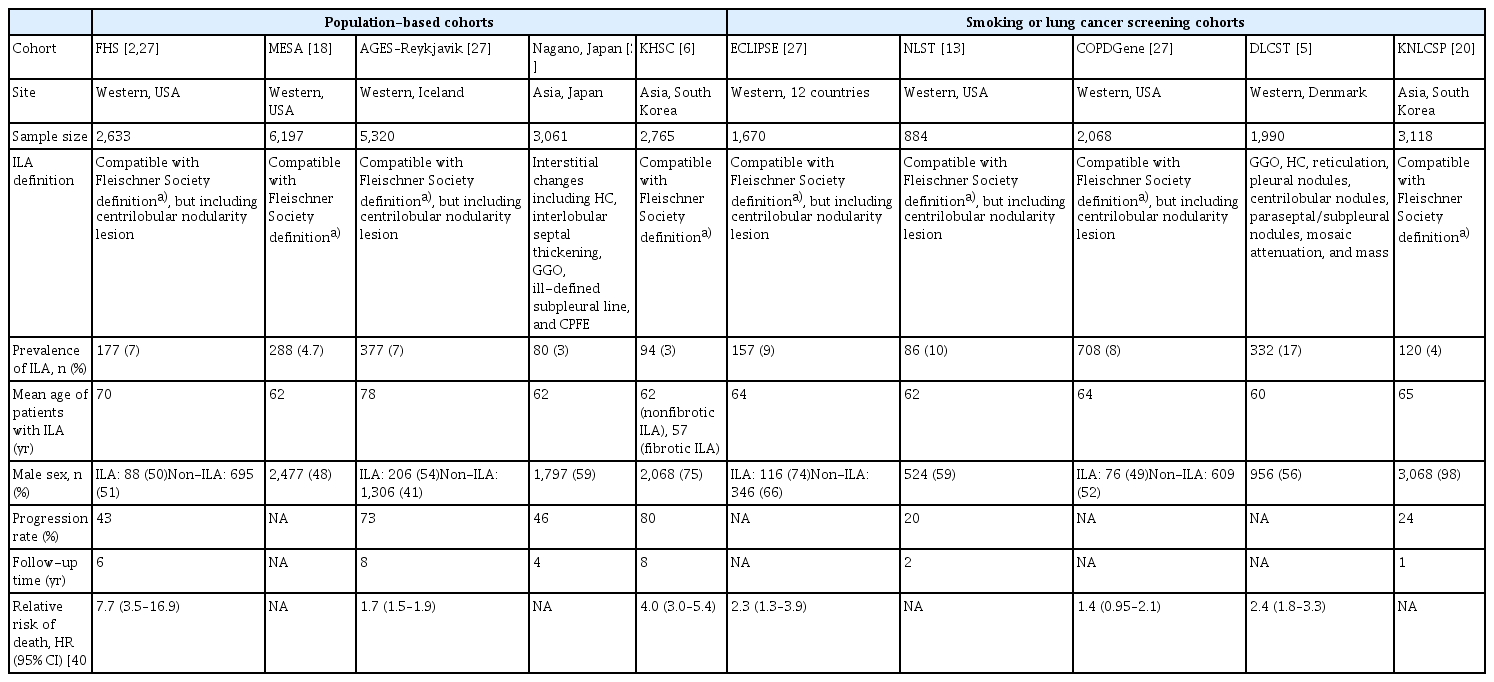

Interstitial lung abnormalities (ILAs) are incidental findings in computed tomography (CT) images of the chest, indicating early-stage interstitial lung disease (ILD) in individuals without a formal clinical diagnosis [1]. Unlike advanced clinical and subclinical forms of ILD, ILAs are typically identified during imaging performed for unrelated medical reasons [1]. With the increasing use of CT for diverse diagnostic purposes, the detection rate of ILAs is anticipated to increase. Previous studies have demonstrated a highly variable prevalence of ILAs across populations, ranging from 3% to 17% (Table 1) [2–6].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the importance of early detection of ILAs, linking them to respiratory symptoms such as chronic cough and breathlessness, reduced lung function, diminished exercise tolerance, and an increased risk of all-cause mortality [5–10]. In addition, ILAs can progress to more severe conditions, including pulmonary fibrosis [9,11]. Despite their clinical significance, they are frequently underreported in radiology reports, even within academic institutions [12]. This review aims to provide clinical practitioners with a concise overview of ILAs by integrating current knowledge on diagnostic criteria, clinical relevance, and management strategies.

DEFINITION OF ILA

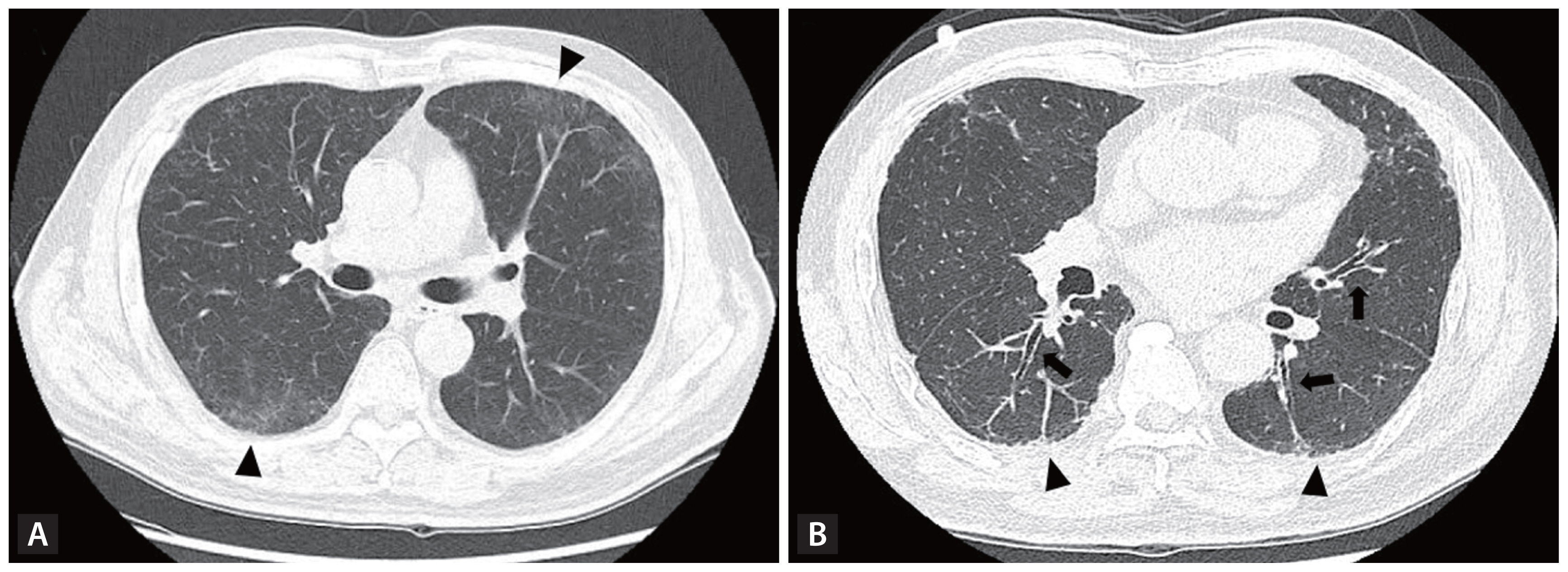

According to the Fleischner Position Paper, ILAs are radiologically defined as incidental CT findings of non-dependent lung parenchymal abnormalities involving at least 5% of any lung zone in individuals without prior suspicion of ILD [1]. These abnormalities include ground-glass opacities (GGOs), a reticular pattern, lung distortion, traction bronchiectasis, honeycombing, and non-emphysematous cysts [1] (Fig. 1). The 5% threshold is used to exclude minimal abnormalities and ensure that only significant findings are considered. Focal or unilateral GGOs, focal or unilateral reticulations, and patchy GGOs involving less than 5% of the lung are categorized as equivocal [1,3,13]. In addition, certain imaging findings are not indicative of ILAs, including dependent lung atelectasis, focal paraspinal fibrosis, smoking-related centrilobular nodularity without accompanying features, interstitial edema (e.g., in heart failure), and aspiration-related findings such as patchy GGOs or a tree-in-bud pattern (Fig. 2) [1].

Chest CT images showing interstitial lung abnormalities. (A) A 60-year-old man with no smoking history or underlying diseases underwent chest CT as part of a health screening. Axial CT image reveals diffuse ground-glass opacities with mild reticulation (arrowheads) in the peripheral region of the left upper lobe and both lower lobes. (B) A 67-year-old man with a 30-pack-year smoking history underwent chest CT for lung cancer screening. Axial CT image shows reticulation (arrowheads) and traction bronchiolectasis (arrows) without honeycombing in the subpleural region of the posterobasal segment of both lower lobes. CT, computed tomography.

Chest CT images showing findings that do not represent interstitial lung abnormalities. (A) Focal paraspinal fibrosis adjacent to thoracic spine osteophytes in the medial right lower lobe (arrowhead). (B) Centrilobular nodularity (arrow) and unilateral mild focal abnormality in the left lower lobe in a heavy smoker (arrowhead). (C) Interlobular septal thickening (arrows) and peribronchovascular bundle thickening (arrowhead) in both lungs in a patient with heart failure. (D) Patch ground-glass opacities and tree-in-bud pattern (arrowheads) in the left lower lobe due to aspiration. CT, computed tomography.

ILAs are categorized based on their distribution and the presence of fibrosis (Fig. 3). These categories include non-subpleural ILAs, which do not have a predominant sub-pleural location; subpleural non-fibrotic ILAs, which have a predominant subpleural location but no fibrosis; and sub-pleural fibrotic ILAs, which have a subpleural location and features of pulmonary fibrosis, such as architectural distortion, traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis, and honeycombing [1]. The presence of subpleural fibrotic ILAs is strongly associated with a higher risk of disease progression and mortality [7,14].

Subcategories of interstitial lung abnormalities. (A) Non-subpleural ILAs: CT image showing multifocal ground-glass opacities with a central predominance in both lungs (arrows). (B) Subpleural non-fibrotic ILAs: CT image showing subpleural ground-glass opacities predominantly in both lower lobes without evidence of fibrosis (arrowheads). (C) Subpleural fibrotic ILAs: CT image showing fibrotic features such as traction bronchiectasis (arrow) with architectural distortion and honeycombing (arrowhead) predominantly involving the subpleural region of both lower lobes. ILA, interstitial lung abnormality; CT, computed tomography.

Differentiating ILAs from clinical and subclinical ILDs requires a thorough clinical evaluation, as the presence of ILAs does not preclude respiratory symptoms or functional impairment. Moreover, abnormalities identified during targeted screening for ILD in high-risk populations–such as individuals with connective tissue disease or a family history of ILD–are categorized as subclinical or preclinical ILD, rather than ILAs, due to their non-incidental nature.

ASSESSMENT OF ILAs

The evaluation of ILAs should include a dedicated chest CT with thin slices (< 1.5 mm) and moderate edge-enhancing reconstruction [1]. High-resolution CT (HRCT) is recommended when the initial scan is incomplete or yields equivocal findings [1,15]. Prone imaging is particularly useful for distinguishing dependent atelectasis from interstitial abnormalities, whereas expiratory imaging aids the identification of lobular air trapping, which may suggest conditions such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis [16,17].

The identification of ILAs has conventionally been the responsibility of experienced radiologists or pulmonologists, relying on visual assessment [2,5–7,13,18]. Although these techniques provide high inter-reader agreement and reliability, they are time-intensive and can lead to discrepancies in distinguishing ILAs from equivocal cases [19]. For instance, a study of 336 health check-up participants revealed discordant ILA classifications between two readers in 49 cases (14.6%). Among these, 42.9% (21 of 49) involved mild, non-dependent lung abnormalities that one reader categorized as ILA and the other considered equivocal [19].

To overcome the challenges associated with conventional methods of identifying ILAs, automated quantification systems employing computational techniques have been developed to enhance accuracy and efficiency [19–24]. These methods include densitometry, local histogram analysis, and advanced artificial intelligence-based texture evaluation, which are effective for quantifying subtle changes in the lung parenchyma [20,22,23,25,26]. Several studies have compared the performance of automated quantitative methods with radiologist assessments in detecting ILAs [19,20,22]. For example, Kim et al. [19] utilized a deep learning-based quantitative system, demonstrating a sensitivity of 67.6%, specificity of 93.3%, and accuracy of 90.5% for identifying ILAs, using a threshold of 5% lung parenchymal abnormalities in at least one lung zone. Similarly, Chae et al. [20] found that deep learning-based texture analysis detected a 4% prevalence of ILAs in the Korean general population. This method achieved 100% sensitivity and 99% specificity, using a lower threshold of 1.8% abnormalities, suggesting the potential for improved accuracy with reduced thresholds. Despite their advantages in reducing clinician workload and mitigating subjective bias, automated quantification systems have limitations. False positives are common, often resulting from suboptimal inspiration or inconsistencies in imaging protocols across vendors, underscoring the need to standardize imaging procedures [19,22].

The development and refinement of quantitative tools for ILA assessment highlight their potential for integration into clinical practice. These tools provide a standardized approach to evaluation, enabling consistent assessments across multiple institutions and facilitating multicenter studies as well as longitudinal monitoring. However, the thresholds and parameters employed by these systems require further optimization to enhance diagnostic accuracy.

PREVALENCE OF ILAs

Recent studies have demonstrated significant variability in the prevalence of ILAs across populations. They are observed in 4–17% of smokers and lung cancer screening cohorts [4,5,13,27,28] and 3–10% of population-based cohorts [2,24,27,29,30]. Furthermore, ILAs have a lower prevalence in Asian populations compared to Western populations. For instance, Tsushima et al. [29] reported a prevalence of 2.6% in the Japanese general population, whereas Chae et al. [20] identified a prevalence of 4% among participants in the Korean National Lung Cancer Screening Program. Conversely, another study reported a 10% prevalence of ILAs in a Western lung cancer screening cohort. The variability in ILA prevalence can be attributed to several factors, including differences in cohort characteristics such as mean age, genetic predispositions, environmental exposures, and imaging protocols. In Lee et al. [6] and Chae et al. [20], which involved Korean cohorts, the use of low-dose chest CT for health or lung cancer screening may have contributed to the lower prevalences observed. Furthermore, the MUC5B promoter polymorphism, a well-recognized risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), is rare in the South Korean population and may partly explain the regional differences in prevalence [31]. Inconsistent definitions of ILAs further complicate prevalence estimates. For example, Tsushima et al. [1,29] defined ILAs as interstitial changes, including honeycombing, interlobular septal thickening, GGOs, ill-defined subpleural lines, and combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, which differs from definitions used in recent studies. The Fleischner Society has provided guidelines to standardize ILA definitions, which have reduced variability in the reported prevalence rates. However, differences in imaging techniques and interpretation contribute to the wide range of prevalence estimates.

RISK FACTORS FOR ILAs

Advanced age is a key risk factor for ILAs, with multiple studies consistently reporting a higher prevalence among older individuals [3,18,22,32]. Data from the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) demonstrated a significant increase in ILA prevalence, increasing from 4% in individuals under 60 years to 47% in those over 70 years of age [32]. Sex differences in ILA prevalence have been observed, with some studies suggesting that ILAs are more common in men than women [13,27]. However, these findings are inconsistent, with other studies reporting no significant differences [3,5,18,30]. Smoking is also a significant risk factor for ILAs, with current smokers and those with greater cumulative exposure (e.g., higher pack-years) exhibiting an increased likelihood of ILA development [13,27,33]. For example, in the FHS and Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility (AGES)–Reykjavik cohorts, Putman et al. [27] found that the ILA group had a higher proportion of current smokers and greater smoking exposure compared to the non-ILA group. However, the association between smoking and ILA presence is not consistently observed across studies. Lee et al. [3] found no significant differences in smoking status or intensity between the ILA and non-ILA groups (ever smokers: 88.3% vs. 90.3%, p = 0.433; smoking quantity: 39.4 vs. 38.4 pack-years, p = 0.692). Importantly, ILAs have a prevalence of 7.9% even among never smokers, underscoring the need for vigilance in identifying these abnormalities regardless of smoking history [34].

Environmental and occupational exposures are significant contributors to the risk of developing ILAs. Salisbury et al. [9] demonstrated that specific environmental exposures were independently associated with the presence of ILAs in a multivariable model adjusted for age, smoking status, MUC5B genotype, and telomere restriction fragment length. These exposures included aluminum smelting (odds ratio [OR] 14.88, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.67–97.73; p = 0.005), lead (OR 2.91, 95% CI 1.05–8.05; p = 0.04), birds (OR 3.37, 95% CI 1.53–7.41; p = 0.003), and mold (OR 3.83, 95% CI, 1.78–8.25; p = 0.001). Similarly, Sack et al. [35], which involved the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) cohort, reported that exposure to vapors, gas, dust, and fumes was associated with a 2.64% increase in high-attenuation areas (95% CI 1.23–4.19%). In addition, self-reported exposure to vapor or gas was linked to a 1.97-fold higher likelihood of ILAs among currently employed individuals (95% CI 1.16–3.35).

The association between ambient air pollution and ILAs has been highlighted in several recent studies [36–38]. Although definitive evidence remains limited, air pollutants such as particulate matter (PM), ozone, nitrogen oxide, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide contribute to pulmonary inflammation and alveolar epithelial injury. These pollutants can induce oxidative stress through the production of reactive oxygen species, including hydroxyl radicals and superoxide anions, as well as promote telomere shortening, which can promote these pathophysiological processes [36]. The MESA Air-Lung Study found a significant association between exposure to nitrogen oxides, a marker of traffic-related air pollution, and the presence of ILAs (OR 1.77 per 40 ppb, 95% CI 1.06–2.95; p = 0.03) [37]. Similarly, in population-based FHS cohorts, an interquartile range difference in 5-year exposure to elemental carbon, a component of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) from traffic emissions, was associated with a 1.27-fold increased likelihood of ILAs (95% CI 1.04–1.55) [38].

Genetic predisposition plays a crucial role in the development of ILAs [18]. The most consistent genetic risk factor for ILA is an increased copy number of a common variant (rs35705950) in the promoter region of the MUC5B gene, which is strongly associated with IPF [2,7,18,30,39,40]. In the MESA longitudinal cohort study, the MUC5B promoter single nucleotide polymorphism (rs35705950) was significantly associated with incident ILA (hazard ratio [HR] 1.73, 95% CI 1.17–2.56; p = 0.01) [18]. This association has been corroborated in multiple cohorts, including the FHS [2,30], COPDGene [40], and AGES–Reykjavik studies [7], where each copy of the variant was associated with a 1.5- to 2.7-fold increased risk of ILAs. Recent genome-wide association studies have further identified novel genetic associations specific to ILAs, such as variants near IPO11 (rs6886640) and FCF1P3 (rs73199442), which are not linked to IPF [40]. These findings underscore both the overlap and distinctions in genetic risk factors between ILAs and IPF, suggesting that ILAs may represent a spectrum of early ILDs.

IMPACT OF ILA ON CLINICAL OUTCOMES

ILA progression

The progression of ILAs varies significantly depending on the cohort type and the duration of the observation period. In the National Lung Screening Trial, approximately 20% of individuals with ILAs demonstrated radiologic progression over a 2-year period [13]. Conversely, Araki et al. [2], which involved the FHS cohort, reported a progression rate of 43% over 6 years, whereas the AGES-Reykjavik study observed an even higher progression rate of 48% over 5 years [7].

Several factors, including advanced age, an increasing number of copies of the MUC5B risk allele, exposure to air pollutants, and specific fibrotic imaging patterns, significantly influence the progression of ILAs [2,7,18,38]. Radiological findings such as subpleural reticular changes, lower lobe predominance, and traction bronchiectasis are associated with higher odds of ILA progression [7,11]. Putman et al. [7] found that these radiological features increased the likelihood of ILA progression by more than 6-fold compared to cases without traction bronchiectasis (OR 6.6, 95% CI 2.3–14.9; p = 0.0004) and lower lobe predominance (OR 6.7, 95% CI 1.8–25; p = 0.004). Similarly, Zhang et al. [11] identified reticulation in initial imaging as an independent predictor of ILA progression (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–3.0; p = 0.004). Conversely, centrilobular nodules are associated with a significantly lower likelihood of ILA progression (OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1–0.5; p = 0.0002) [7].

The progression of ILAs may influence physiological changes, including a decline in lung function [2,3]. FHS demonstrated that individuals with progressive ILAs experienced an accelerated decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) compared to those with non-progressive ILAs, with a reduction of 25 mL per year (standard error [SE]: ± 11 mL; p = 0.03) [2]. Similarly, in a study that involved patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), those with progressive ILAs exhibited significantly higher rates of annual decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 s and FVC compared to those without progression (β ± SE: −38.3 ± 5.7 mL/year; p = 0.16 and −51.2 ± 0.7 mL/year; p = 0.06, respectively) [3]. However, the FVC decline in patients with ILA progression was less pronounced than the decline typically observed in IPF [41].

Considering the impact of ILA progression, there is an increasing need for simple biomarkers to predict progression at an early stage. Axelsson et al. [42] explored serum protein biomarkers for predicting ILA progression through proteomic analysis in the AGES-Reykjavik cohort. In this cohort, 121 proteins were associated with ILA progression. The proteins with the highest odds for progression included SFTB (OR 3.08, 95% CI 2.56–3.69; p = 1.59 × 10−39), WFDC2 (OR 2.72, 95% CI 2.25–3.29; p = 4.90 × 10−25), growth differentiation factor-15 (OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.79–2.55; p = 3.01 × 10−17), and cathepsin H (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.70–2.40; p = 1.72 × 10−15). Further studies are needed to identify novel biomarkers and validate these findings for the early prediction of ILA progression.

ILA represents partially undeveloped stages of IPF or progressive pulmonary fibrosis [43]. The progression of ILA toward IPF is a significant clinical concern due to the overlap in risk factors and disease characteristics [2,7,18,38,43]. Key risk factors common to both ILA and IPF include aging, smoking, environmental pollutants such as nitrogen oxides, occupational exposures (e.g., vapors, gas, dust, and fumes), and genetic susceptibility, particularly MUC5B (rs35705950 allele). However, the time interval and frequency with which ILA progresses to IPF remain unclear. A large cohort study is currently underway to investigate the natural course of IPF and progressive pulmonary fibrosis from the asymptomatic stage in patients with ILA [44]. The results will enhance our understanding of disease progression and facilitate the identification of patients at risk for developing IPF.

Mortality

ILAs are associated with increased mortality across various populations, including the general population, smokers, and lung cancer screening cohorts [2,7,14,27]. In the FHS and AGES–Reykjavik cohorts, radiological progression of ILAs was most strongly associated with increased all-cause mortality [2,7]. In addition, in the AGES–Reykjavik cohort, ILAs were significantly associated with increased respiratory disease-related mortality (HR 2.4, 95% CI, 1.7–3.4; p < 0.001), even after adjusting for age, sex, race, body mass index, and smoking history [27]. ILAs were also significantly associated with mortality after adjusting for multimorbidity, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, COPD, and cancer in the FHS cohort (HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.23–3.08; p = 0.0042) and the AGES–Reykjavik cohort (HR 1.60, 95% CI 1.41–1.82; p < 0.0001). The mortality risk associated with ILAs was similar to that of other common chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, COPD, and cancer [45]. In the AGES–Reykjavik cohort, ILA was associated with an increase in respiratory-related mortality, suggesting that the progression of lung fibrosis and worsening of comorbid conditions due to decreased lung function may contribute to elevated mortality [27,46]. However, considering that mortality rates exceed the expected progression rate to clinically detectable ILD, the additional mortality risk in patients with ILA may be related to age-related vulnerabilities or comorbidities unrelated to lung disease [1,27].

Lung cancer development and outcomes

ILAs impact lung cancer development, treatment outcomes, and cancer-related mortality [46]. A meta-analysis of three studies on ILA demonstrated that individuals with ILA have a significantly higher incidence of lung cancer compared to those without ILA (risk ratio 3.85, 95% CI 2.64–5.62; I2 = 22%) [46]. In addition, ILAs may complicate the treatment of lung cancer. Preexisting ILAs are associated with a higher risk of radiation pneumonitis [47,48] and immune checkpoint inhibitor-related ILDs [49] in lung cancer patients. Furthermore, in patients with early-stage cancer undergoing surgical resection, the presence of ILAs increased the risk of postoperative pulmonary complications, including pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory failure, bronchopleural fistula, empyema, prolonged air leak, and pneumothorax (OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.02–1.13; p = 0.004) [50]. These findings highlight the importance of careful monitoring and management of patients with ILAs, particularly those undergoing lung cancer therapy.

ILA MANAGEMENT AND FOLLOW-UP

Structured approaches to the management and follow-up of patients with ILAs are crucial to reduce the risk of disease progression and improve clinical outcomes. Upon identification of ILA, a comprehensive clinical evaluation is needed. This includes obtaining a detailed patient history, focusing on symptoms such as chronic cough, dyspnea, and exposure to risk factors such as smoking and occupational hazards [1,15]. Pulmonary function tests should be conducted to assess baseline lung function, with particular attention to parameters such as FVC and diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide [1,15]. These investigations can identify clinically significant ILD, indicating the extent of functional impairment and guiding further management.

Serial chest imaging is crucial for monitoring ILAs. HRCT with thin sections is needed to assess changes in lung parenchyma over time. It is essential to maintain standardized imaging protocols to ensure consistency and comparability of results [1]. Radiologists should focus on identifying features indicative of progression, such as increased reticulation, honeycombing, and traction bronchiectasis [15]. Quantitative CT analysis can be used to objectively assess the extent and severity of ILAs, helping to detect subtle changes that may indicate progression [51].

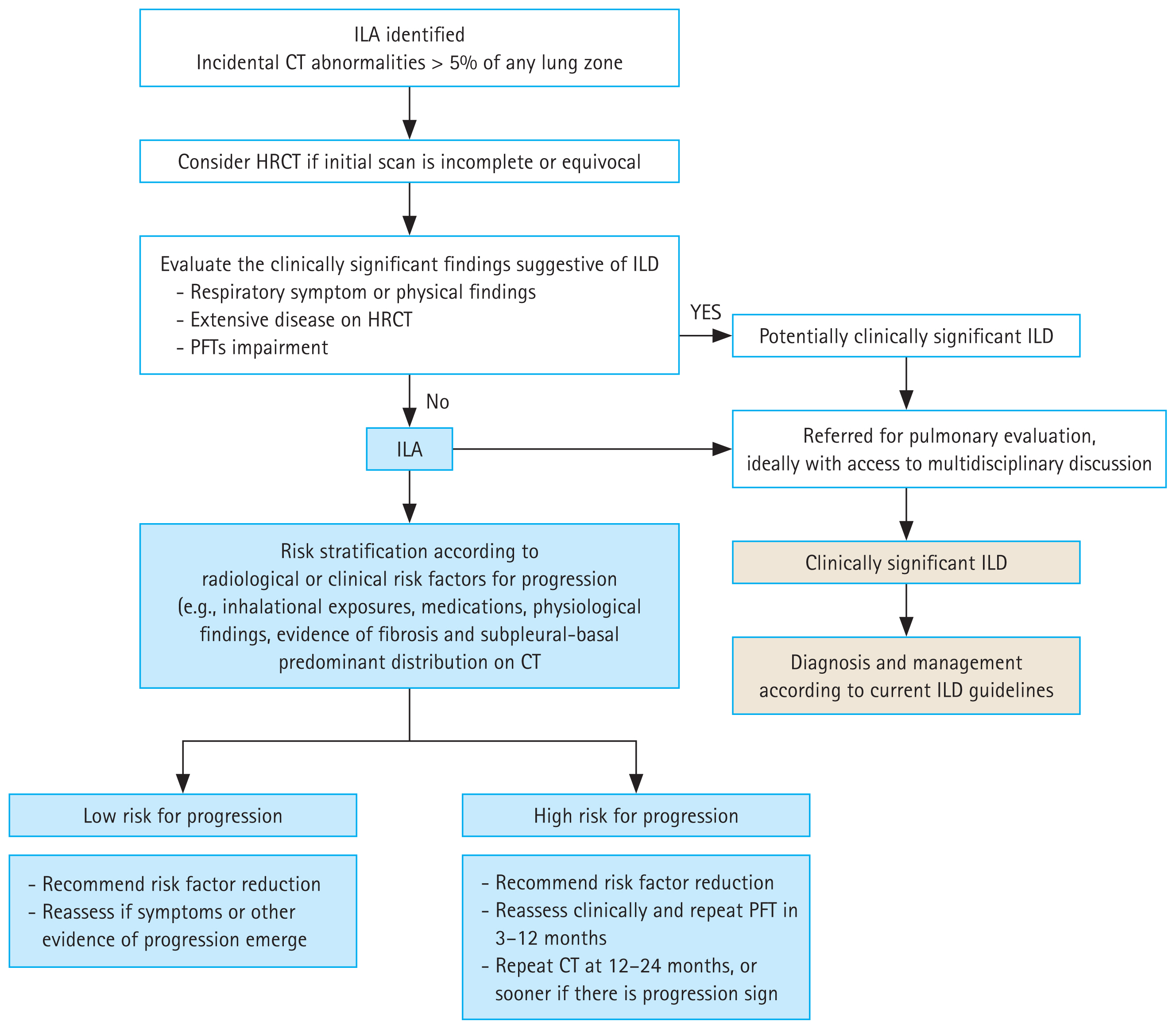

Monitoring and management strategies for ILAs should be individualized according to the patient’s risk profile and disease characteristics (Fig. 4). Factors such as fibrotic features on radiological imaging, including architectural distortion with traction bronchiectasis or honeycombing and subpleural basal predominance, the presence of the MUC5B promoter polymorphism, and patient demographics (e.g., age, smoking status, and environmental exposures) may influence the likelihood of progression to ILD [1,43]. In cases where ILAs show extensive fibrosis with impaired lung function or are associated with significant respiratory symptoms, referral to an ILD specialist for further evaluation and appropriate treatment, such as antifibrotics, should be considered. Once the possibility of ILD has been ruled out, ILAs should be stratified according to their risk factors for progression. Individuals without risk factors should be monitored until the onset of respiratory symptoms or other signs of disease progression [1,15], whereas those with risk factors should be followed regularly every 12–24 months or sooner if new respiratory symptoms occur or lung function declines [1,15]. However, the optimal interval and duration of follow-up remain unclear. Park et al. [51] suggested that a follow-up CT every 3 years may be appropriate for individuals with initially detected ILA, whereas those at high risk due to extensively fibrotic ILA and honeycombing require more frequent CT examinations. If ILA progression is suspected, the decision to perform diagnostic procedures such as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery-assisted biopsy, bronchoalveolar lavage, or cryobiopsy should be individualized based on clinical presentation and HRCT findings. Patients with fibrotic ILA exhibiting basal and peripheral distribution are at an increased risk of progression and may have subclinical ILDs, which makes lung biopsy potentially helpful for diagnosing IPF or specific ILDs [43]. However, in cases where HRCT reveals a usual interstitial pneumonia pattern and the multidisciplinary team categorizes it as subclinical IPF, invasive tests may not be necessary [43].

Follow-up and management strategy for interstitial lung abnormalities. This figure is adapted with modifications from a scheme in the Position Paper of the Fleischner Society [1]. ILA, interstitial lung abnormality; CT, computed tomography; HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography; ILD, interstitial lung disease; PFT, pulmonary function test.

A multidisciplinary approach involving radiologists, pulmonologists, and primary care providers is crucial for the effective management and follow-up of ILAs [43]. In addition, lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and vaccination against respiratory infections, are essential components in managing ILA. By combining comprehensive clinical assessment, standardized imaging protocols, and evidence-based risk stratification, healthcare providers can improve the prognosis and prevent progression to severe forms of ILD. Further studies and the integration of novel diagnostic tools, including advanced imaging techniques and new biomarkers, are needed to enhance management strategies and clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

This review emphasizes the clinical significance of ILAs, which are incidental findings in chest CT images that may indicate early ILDs. Although the prevalence of ILAs varies across different populations, their detection is crucial due to their potential risk of progression to severe lung conditions, such as fibrosis, and their association with increased mortality. Advances in imaging technology, particularly automated quantitative systems, have significantly enhanced the accuracy of ILA assessments, enabling early and accurate detection. Effective management requires a multidisciplinary approach tailored to individual risk profiles to mitigate disease progression and improve outcomes. Further studies are needed to refine diagnostic criteria, enhance imaging techniques, and develop targeted therapies to better understand and treat ILA.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Ju Hyun Oh: conceptualization, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing; Jin Woo Song: conceptualization, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Basic Science Research Program (NRF-2022R1A2B5B02001602) and the Bio and Medical Technology Development Program (NRF-2022M3A9E4082647) of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, South Korea. This work was also supported by the National Institute of Health research project (2024ER090500) and by Korea Environment Industry and Technology Institute through Core Technology Development Project for Environmental Diseases Prevention and Management Program funded by Korea Ministry of Environment (RS-2022-KE002197), South Korea.