Characteristics and treatment patterns in older patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer (KCSG HN13-01)

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Treatment decisions for locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (LA-HNSCC) are complicated, and multi-modal treatments are usually indicated. However, it is challenging for older patients to complete treatments. Thus, we investigated disease characteristics, real-world treatment, and outcomes in older LA-HNSCC patients.

Methods

Older patients (aged ≥ 70 years) were selected from a large nationwide cohort that included 445 patients with stage III–IVB LA-HNSCC from January 2005 to December 2015. Their data were retrospectively analyzed and compared with those of younger patients.

Results

Older patients accounted for 18.7% (83/445) of all patients with median age was 73 years (range, 70 to 89). Proportions of primary tumors in the hypopharynx and larynx were higher in older patients and older patients had a more advanced T stage and worse performance status. Regarding treatment strategies of older patients, 44.5% of patients received concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT), 41.0% underwent surgery, and 14.5% did not complete the planned treatment. Induction chemotherapy (IC) was administered to 27.7% (23/83) of older patients; the preferred regimen for IC was fluorouracil and cisplatin (47.9%). For CCRT, weekly cisplatin was prescribed 3.3 times more often than 3-weekly cisplatin (62.2% vs. 18.9%). Older patients had a 60% higher risk of death than younger patients (hazard ratio, 1.6; p = 0.035). Oral cavity cancer patients had the worst survival probability.

Conclusions

Older LA-HNSCC patients had aggressive tumor characteristics and received less intensive treatment, resulting in poor survival. Further research focusing on the older population is necessary.

INTRODUCTION

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is a heterogeneous group of epithelial malignancies that arise from the sinus, oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx. HNSCC is the sixth most common malignancy worldwide, with 532,000 new cases every year [1]. In Korea, HNSCC is the tenth most common malignancy, with around 4,700 new cases each year and around one third of new cases occur in older patients with aged ≥ 70 years [2,3]. HNSCC is common in the older population, and thus, its incidence is expected to increase soon in countries with an aged population, such as Korea [4,5]. Therefore, interests focusing on the treatment and care for older HNSCC patients. In particular, multi-modal treatment approaches have significant potential to result in better outcomes in locally advanced (LA)-HNSCC patients. Considering tumor and patient characteristics, LA-HNSCC patients are recommended to undergo surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, either sequentially or simultaneously.

However, compared with younger patients, older patients are more likely to be frail, and thus, aggressive treatment modalities can be dangerous [6]. Older patients also tend to have impaired functional status and more comorbidities, which can also affect treatment compliance. Furthermore, regarding the occurrence of treatment-related adverse events, older patients have a higher risk of treatment interruption or early discontinuation than younger patients, thus affecting survival and quality of life among the older population [7,8]. Therefore, proper treatment planning for older patients is warranted. Despite this, however, there are limited reports regarding tumor characteristics and treatment patterns in older LA-HNSCC patients. Thus, in this study, we focused on older patients (aged ≥ 70 years) who were included in a large nationwide cohort of patients with stage III–IVB LA-HNSCC. This study aimed to investigate and compare differences in clinical characteristics, real-world treatment patterns, outcomes, and prognostic factors between older and younger patients.

METHODS

Study population

This large nationwide cohort included 445 patients with histologically proven LA-HNSCC from January 2005 to December 2015 from 13 nationwide referral hospitals in Korea (KCSG HN 13-01). LA-HNSCC was defined as clinical stage III–IVB based on the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging. Study patients aged ≥ 20 years with primary squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, oral cavity, or nasal cavity were included irrespective of their treatment. Patients with pathologically confirmed squamous cell carcinoma of the cervical lymph node without primary site were regarded as having cancer of the head and neck origin and were also included in the analysis. We excluded patients with nasopharyngeal cancer, distant metastasis at initial diagnosis, or a history of other malignancies detected within 3 years of HNSCC diagnosis.

The chronological definition of the “older” has not yet been established. However, 70 years of age is considered a transitional point of senescent change, and therefore, 70 years of age is frequently used as a reference point in many clinical trials or geriatric evaluations in oncology [9,10]. Therefore, in this study, we defined “older” as those aged ≥ 70 years. Each participating hospital treated LA-HNSCC patients based on the principle of using multidisciplinary care treatment protocols. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board in main hospitals (Seoul National University Hospital and Chungnam National University Hospital: IRB-H-1304-089-481, 2013-10-003) and each participating center. All analyses were conducted retrospectively. Ethics Committee of each participated hospital approved this study without the need for individual subject consent.

Study outcomes and statistical analysis

The primary outcome of this study was to demonstrate the therapeutic patterns of real-world LA-HNSCC treatment among older patients and compare them with those of patients < 70 years. The secondary outcome was to determine overall survival (OS) based on treatment strategy or primary site in older patients. OS was defined as the time from the date of HNSCC diagnosis to the date of death irrespective of the cause.

To compare patients’ characteristics between groups, chi-square and independent t test were used. Treatment response was assessed using RECIST version 1.1. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was used to determine risk factors for OS under the proportional hazards assumption. Two-sided p value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 16.0 software (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Among 445 LA-HNSCC patients who were examined during the study period, 83 (18.7%) were older (age ≥ 70 years) and had a median age of 73 years (range, 70 to 89). Approximately 93% (n = 77) of older patients were male, whereas among younger patients, only 85% (n = 308) were male (p = 0.062). Older patients had worse performance status (PS) than younger patients (p = 0.014). History of smoking and alcohol intake were not different between older and younger patients. Primary tumor locations in older patients included the oropharynx in 26.5% of cases, followed by oral cavity (24.1%), hypopharynx (17.0%), larynx (18.1%), and other sites (14.5%). Other sites included the maxillary sinus, nasal cavity, ethmoid sinus, and head and neck squamous carcinoma with unknown primary tumor site. The proportion of older patients with tumor location in the hypopharynx, larynx, and other sites was higher than that of younger patients, while the proportion of older patients with tumor location in the oropharynx was lower than that of younger patients (p < 0.001). Regarding T classification, higher proportion in older patients had T4a/b stage than younger patients (p = 0.018). Among 25 older patients who were tested for human papillomavirus (HPV) status, 40% (10/25) were positive. Patients’ demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

Treatment strategy

Treatment history for LA-HNSCC patients was divided into a definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) group, surgery group, and inadequate group according to the decision of multidisciplinary team of each institution (Fig. 1). Among older patients 44.5% received definitive CCRT, whereas 41.0% underwent surgery. The remaining 14.5% did not receive any treatment or further adequate treatments after induction chemotherapy (IC) with the aim of cure such as CCRT or surgery. Meanwhile, 53.0% of patients aged < 70 years received definitive CCRT, 42.3% underwent surgery, and 4.7% received inadequate treatment. The proportion of patients with inadequate treatment was approximately three times higher among older patients than among younger patients.

Flowchart for the treatment of locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by age of 70 (n = 445). CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; CTx, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; Tx, treatment.

Regarding IC, 27.7% (23/83) of older patients received IC, whereas 37.2% (135/362) of younger patients received IC (p = 0.100). Among 83 older patients, eight (9.6%) receiving IC did not receive subsequent therapy (Fig. 1 in inadequate group). Approximately 72% of older patients and 90% of younger patients underwent combined treatment modalities.

Treatment characteristics

Treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Among 158 patients receiving IC, 23 (14.6%) were older. For IC regimen, the choice of chemotherapy differed according to 70 years of age (p < 0.001). In older patients, fluorouracil and cisplatin (FP) was the most preferred (47.9%) regimen. However, docetaxel and cisplatin (DP) was the most chosen IC regimen in patients aged < 70 years. Overall treatment response was similar between the age groups (p = 0.448); complete response, partial response, and stable disease were 17.4%, 47.8%, and 30.4%, respectively, in older patients and 15.6%, 56.3%, and 17.8%, respectively, in younger patients.

Characteristics of therapeutics with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by age group

Among the 229 patients receiving definitive CCRT, the chemotherapy regimen was not different between the age groups (p = 0.497). The preferred regimen was weekly cisplatin in 62.2% of older patients and 57.3% of younger patients. Among the 11 patients receiving other regimens, six received cetuximab (two were older and four were younger patients). The overall response of definitive CCRT was similar between older and younger patients (p = 0.534).

Study outcomes

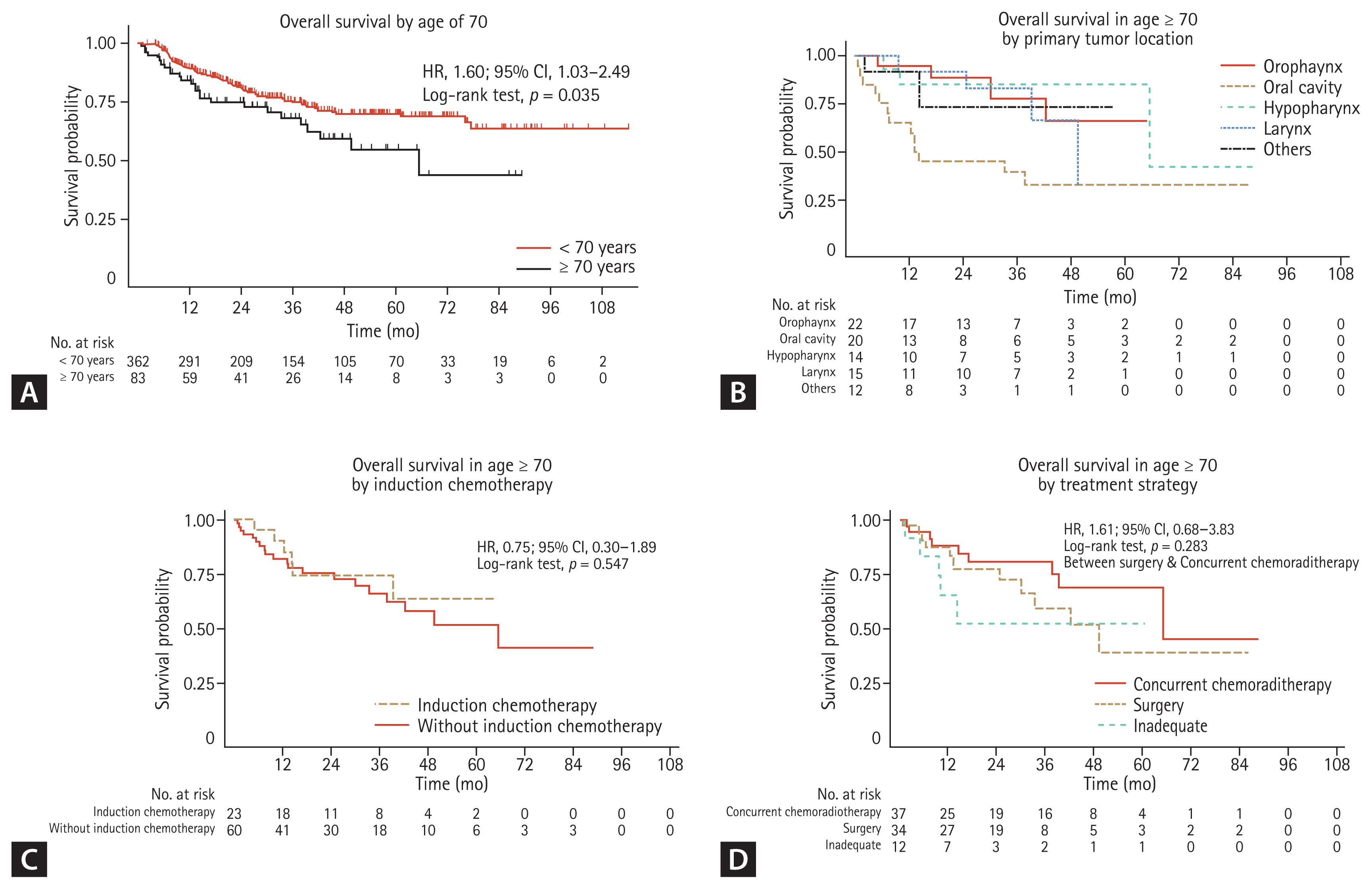

For 445 LA-HNSCC patients, 113 deaths were observed with a median follow-up period of 39.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 35.4 to 43.1). For 83 older patients, 26 (31.3%) patients died with a median follow-up time of 30.8 months (95% CI, 24.6 to 44.3). The older patients had a significantly shorter median OS than younger patients (65.5 months vs. not reached: hazard ratio [HR], 1.60; 95% CI, 1.03 to 2.49; p = 0.035) (Fig. 2A). The 12- and 24-month survival rates were 84.5% (95% CI, 0.74 to 0.91) and 75.1% (95% CI, 0.63 to 0.84) in older patients, and 89.6% (95% CI, 0.86 to 0.92) and 80.8% (95% CI, 0.76 to 0.85) in younger patients, respectively. Regarding OS in the context of primary tumor location, median OS was 13.4 months (95% CI, 5.4 to not reached) in oral cavity, 49.6 months (95% CI, 24.8 to not reached), 65.5 months (95% CI, 65.5 to not reached) in hypopharynx, and not reached in oropharynx: older patients with oral cavity tumors had the worst probability of survival (p = 0.03) (Fig. 2B).

(A) Overall survival by age of 70 (n = 445). (B) Overall survival by primary tumor site in age ≥ 70 (n = 83). (C) Overall survival by induction chemotherapy in age ≥ 70 (n = 83). (D) Overall survival by treatment strategy in age ≥ 70 (n = 83). HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

IC administration did not affect median OS (not reached in IC vs. 65.5 months without IC) in older patients (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.30 to 1.89; p = 0.547) (Fig. 2C). Regarding treatment strategies in older patients, the 12- and 24-month survival rates were 88.3% (95% CI, 0.72 to 0.95) and 80.8% (95% CI, 0.62 to 0.92) in CCRT group, 87.5% (95% CI, 0.70 to 0.95) and 77.4% (95% CI, 0.58 to 0.89) in surgery group, and 65.6% (95% CI, 0.32 to 0.86) and 52.5% (95% CI, 0.19 to 0.78) in inadequate group, respectively. Survival probabilities were not significantly different between those receiving CCRT and those undergoing surgery (HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 0.68 to 3.83; p = 0.283) (Fig. 2D). Patients who did not undergo adequate treatments had the poorest OS.

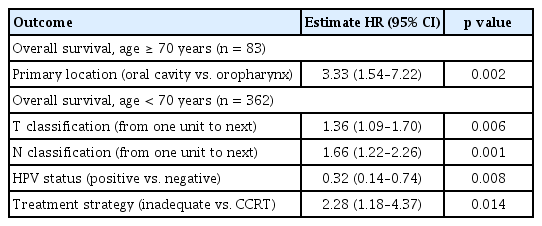

Multivariate analyses of OS

In each age group, uni- and multivariate analyses identified different survival-related risk factors (Table 3, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). In older patients, oral cavity primary tumor location (compared with the oropharynx) was a strong and independent predictor for poor OS (HR, 3.33; 95% CI, 1.54 to 7.22; p = 0.002) (Table 3, Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, in younger patients, tumor factors, including advanced T or N stage, and HPV status were independent prognostic factors. Additionally, the failure to receive an adequate treatment was a strong predictor for poor OS (HR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.18 to 4.37; p = 0.014) (Table 3, Supplementary Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective nationwide investigation of a Korean cohort of patients with stage III–IV LA-HNSCC, older patients accounted for 18.7% (83/445) of all patients. Compared with younger patients, older patients have poor clinical characteristics and poor survival probabilities. The proportion of advanced T stage or poor PS was higher among older patients than among younger patients, while the proportion of older patients with oropharyngeal cancer or HPV positive cancer was lower than that of younger patients. In particular, older patients with oral cavity cancer had the worst OS. In previous epidemiological studies on geriatric patients, a greater proportion of oral cavity or larynx tumors were reported, but the proportion of oropharyngeal cancer was low [4,5,11]. Moreover, patients with oral cavity cancer, especially the older population, had a significantly poor survival [12]. In addition, although HPV is known to be a good prognostic factor in younger patients with oropharyngeal cancer, it is infrequently reported in older patients, which is also consistent with the results of this study [13–15]. Altogether, the evidence indicates that older patients have poor prognostic tumor factors (Fig. 2A).

Treatment patterns were similar between the two age groups (≥ 70 years vs. < 70 years) (Fig. 1). There was no survival difference according to treatment modalities such as CCRT or surgery (Fig. 2D) or administration of IC (Fig. 2C). The proportion of older patients who completed their planned treatments was lower than that of younger patients (Fig. 1). The survival of older patients who did not finish their planned treatments tended to be poor (Table 3).

Still, the role of age as a prognostic factor is not clearly defined in LA-HNSCC. Previous retrospective or epidemiologic-based analysis of various tumor status or treatment conditions revealed that chronologic age was not a significant prognostic factor [16–18]. Furthermore, there is limited data on the survival of older LA-HNSCC patients undergoing multi-modal treatments. In a large-sized study using a cancer registry, older patients aged ≥ 70 years had a two-fold poorer survival than younger aged patients. In a subgroup analysis of patients with stage III or IV laryngeal cancer, patients who received single modality treatment had extremely poor survival than all other patients [19]. In fact, in the real-world practice, LA-HNSCC patients aged ≥ 70 years tend to receive less-aggressive strategies [20]. In our analysis, older patients received weaker IC and CCRT intensity regimens. Eight of 12 patients who received IC did not receive definitive treatment. The failure to complete planned treatments among older patients was associated with a poor survival tendency, although owing to the small number of patients, this difference was not statistically significant. Consequently, in our study, treatment-related factors and poor tumor-related factors among older patients might contribute to poor survival outcomes compared with those among younger patients.

In the clinical practice, treatment strategies for LA-HNSCC are decided through multidisciplinary consultation and considering multifaceted clinical factors. In our analysis, surgery and definitive CCRT as primary treatment was performed in 41.0% and 44.6% of older patients, respectively. As expected, there was no significant difference in survival with each treatment strategy. Approximately 27.7% (23/83) of older patients received IC as initial treatment. Among them, upfront administration of IC did not show statistical difference in survival. There were no significant differences in survival among treatment modalities; however, there were differences especially in application of chemotherapeutic agents in ICT and CCRT for older patients comparing with younger patients.

In the older group, only one patient received docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (TPF) as IC treatment, which is regarded as a standard regimen of IC, whereas 30.4% of younger patients who received IC were treated with TPF. Most (91.3%) older patients received doublet regimens such as DP or FP for IC. Though the intensity of doublet regimen might be weaker than triple regimen of TPF, the facts that substantial portion of older patients receiving IC did not continue further definitive treatment suggest the physician need to focus on safety rather than the effectiveness of specific treatments.

The reason of the majority of patients who received IC were treated with doublet regimen is suspected from oncologist’s concern for frailty of older patients. To obtain the best efficacy through IC, three cycles of treatment with TPF is the strong recommended regimen because IC using TPF regimen provided survival benefit compared to FP in phase III clinical trials and meta-analysis [21–24]. However, TPF issued because of its toxicities. TPF showed more incidence of grade 3–4 neutropenia, febrile neutropenia and neutropenic infection compared to FP [22,23]. In addition, IC with TPF is discussed because it could compromise the following treatment because of toxicity. In a CONDOR study, only 22% of the patients received CCRT with cumulative dose of cisplatin > 200 mg/m2 after three cycles of IC with TPF [25]. Also, in a phase III trial that compared TPF-IC or FP-IC followed by CCRT versus definitive CCRT alone, a lower proportion of patients in the TPF-IC arm could receive CCRT than that of patients in the FP-IC arm [26]. Such results indicate that IC using triplet regimen can decrease the chances of receiving CCRT and also decrease the dose of therapeutic cisplatin combined with CCRT. Serious adverse events occurring during IC can affect further treatment or decrease treatment intensity, which consequently can affect patients’ chances of being cured. However, it is important to note that in our analysis, despite the low intensity of IC, survival did not differ between the IC and non-IC groups. Therefore, IC with doublet regimen rather than triple regimen is recommendable for older patients. Given the lack of studies regarding the best IC regimen for older patients, a well-organized study aiming to identify the most suitable IC regimen for older patients is needed to avoid unnecessary chemotherapy-related toxicities and achieve better treatment outcomes.

In a group of definitive CCRT, 24.3% (9/37) of older patients received CCRT after IC and 75.7% (28/37) received definitive CCRT as the primary treatment. There was no significant difference in selecting a concomitant chemotherapy regimen between older and younger patients in Korea. However, meaningful differences in the efficacy between a weekly or 3-weekly cisplatin during CCRT are not yet clearly defined. In a previous retrospective study conducted in Korea, weekly cisplatin showed comparable therapeutic outcomes compared with 3-weekly cisplatin [27]. Because weekly cisplatin regimen is more compliant and has less toxicities related to myelosuppression, nephrotoxicity, and emesis, weekly cisplatin might be more considerable in older patients [28]. In addition, survival of patients who received CCRT was not different from that of patients who underwent surgery.

This study had some limitations. First, this study was retrospectively designed; therefore, exact information regarding comorbidities, treatment toxicities, and quality of life could not be obtained. Thus, we could not evaluate the correlation between these factors and treatment results in detail. However, because LA-HNSCC patient data for this study were retrieved from 13 nationwide referral hospitals, the data reflect of real treatment patterns for older patients in Korea. Second, patients with various primary sites of head and neck cancer were included, but interpretation of specific cancer status, especially regarding HPV positivity, needs to be performed with caution because we could only obtain information on HPV status in 30.1% of patients. In conclusion, we defined poor tumor characteristics and real-world treatment patterns of older LA-HNSCC patients in Korea. Older LA-HNSCC patients had aggressive tumor characteristics and received less intensive treatment, which resulted in poor survival, especially in cases of oral cavity cancer. There were no survival differences among treatment modalities. Future research focusing on older patients is necessary to determine an optimal treatment strategy that can improve survival.

KEY MESSAGE

1. Older locally advanced (LA)-head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients had aggressive tumor characteristics.

2. Older LA-HNSCC patients received less intensive treatments during concurrent chemoradiotherapy or induction chemotherapy.

3. Older LA-HNSCC patients had a higher risk of death comparing to younger patients especially in patients with oral cavity cancer.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HA16C0015) (1720150). The research was supported (in part) by the Korean Cancer Study Group (KCSG) and KCSG data center. We thank Jiyun Mun from the KCSG data center.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.