Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the University of California–Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium Gastrointestinal Tract instrument in patients with systemic sclerosis

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is associated with a wide range of gastrointestinal (GI) changes. The University of California–Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium Gastrointestinal Tract (UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0) instrument is a self-administered GI assessment instrument for patients with SSc. We developed a Korean version of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 instrument and evaluated its reliability and internal consistency.

Methods

The participants were 37 Korean patients with SSc. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 were performed according to international standardized guidelines. We evaluated reproducibility by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficients and assessed the internal consistency of the Korean version of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0. We assessed its construct validity by evaluating its correlations with the Short Form Health Survey version 2 and EQ-5D scores by means of Spearman correlation analyses.

Results

Patients with SSc were mostly women (89.19%) with a mean age of 52.2 years, median disease duration of 24 months, and median modified Rodnan total skin score of 4. The median total GIT score on the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 was 0.3. The UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 Korean version showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α of total GIT score = 0.863). Most domains of the ULCA SCTC GIT 2.0 were correlated with those of the EuroQol (EQ)-5D score.

Conclusions

The Korean version of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 has acceptable internal consistency, reliability, and validity. Therefore, it can be used to assess GIT involvement in Korean patients with SSc.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune disease characterized by endothelial dysfunction, immune dysregulation, and excessive collagen deposition, and is of unknown etiology. Individual patients manifest these three components to varying degrees, resulting in a heterogeneous clinical presentation [1]. A recent Korean nationwide population-based study reported a prevalence of SSc of 77.7 per million population [2]. The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is the most commonly involved organ and affects the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with SSc. High-resolution manometry (HRM) shows a high level of diagnostic accuracy and reproducibility for esophageal involvement even in asymptomatic patients with SSc [3].

Outcome measurements are important in clinical trials and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) can be useful for monitoring symptoms of SSc [4]. Khanna et al. [5] developed the University of California–Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium Gastrointestinal Tract Instrument (UCLA SCTC GIT) 2.0, a comprehensive self-administered survey, which has been translated and validated in the United Kingdom, Canada, France, The Netherlands, Romania, Italy, Turkey, and Singapore [5–12]. The UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 has been used in randomized placebo-controlled trials to evaluate gastrointestinal symptoms and immune parameters in SSc [13]. It was developed to assess the severity of GIT symptoms and their impacts on HRQoL and consists of 34 items with seven subscales, assessing reflux (eight questions), distension/bloating (four questions), fecal soilage (one question), diarrhea (two questions), social functioning (six questions), emotional well-being (nine questions), and constipation (four questions) [5]. Ethnic and geographical differences are closely related to the prevalence of GIT symptoms in the general population [14,15]. Conceptual differences between quality of life (QoL) domains and attitudinal differences toward GIT features according to ethnicity exist among patients with SSc [16]. However, to date, few Asian adaptations of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 questionnaire are available.

We translated the instrument into Korean and assessed the acceptability, feasibility, reliability, and construct validity of it for evaluating perception of GIT symptoms.

METHODS

Patients and data collection

This was a two-phase cross-sectional study involving translation and adaptation into the target language, followed by validation. Thirty-seven patients with SSc were consecutively recruited between July and October 2017. The patients were diagnosed using the 2013 American College of Rheumatology SSc criteria in the SSc Clinic of Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital [17]. For proper sample size calculation, the number of subjects was determined according to a previous study [5]. Two-sided tests (alpha = 0.05, power = 80% [beta = 0.2]) were performed with the correlation coefficient rho set to 0.2 to 0.6. A rho value of 0.2 indicated a minimum number of subjects of 30. Taking into consideration a 20% dropout rate, 37 subjects were included in this study.

SSc is classified as limited cutaneous (lc) or diffuse cutaneous (dc) systemic disease according to the distribution of skin involvement [18]. For each patient, the following data were collected: demographic characteristics, body mass index (BMI), Raynaud’s phenomenon, and the extent of skin thickening. The extent of skin thickening was evaluated using the modified Rodnan total skin score (mRSS). Laboratory findings, including serum levels of anti-nuclear, anti-centromere, anti-topoisomerase, and anti-RNP antibodies, were also recorded. We investigated internal organ involvement including digital ulcers, SSc-associated interstitial lung disease (as represented by pulmonary function), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD; by esophagogastroduodenoscopy, EGD) [19], scleroderma renal crisis (defined as malignant hypertension with acute renal insufficiency occurring during the course of SSc) [20], and heart involvement including pulmonary arterial hypertension (defined as a mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥ 20 mmHg, pulmonary artery wedge pressure < 15 mmHg, and pulmonary vascular resistance > 3 Wood units measured during right-heart catheterization at rest according to the Sixth World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension) [21]. Pulmonary function was assessed by determining the functional vital capacity (FVC; % predicted) and diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO; % predicted) (corrected for hemoglobin). Patients with an incomplete clinical assessment were excluded. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research of Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital (IRB no. SCH 2017-07-029). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Translation of the Korean version of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0

The English-language version of the instrument is available at https://umich.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_3eBP4A4umBwnSvj/ and was used in this study with the permission of Professor Khanna. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the instrument were performed according to the published recommendations [22,23]. The proposed steps were synthesis of translation, back translation, expert committee review, and pre-testing. First, three people of different backgrounds (e.g., one medical and two non-medical) independently performed a forward translation of the instrument from the English-language to the Korean language. The adjustments made were combined by consensus among the translators. Then back translation was performed by two independent bilingual native speakers of English, who were blinded to the original English-language version. The two (forward and back) non-medical translators are very familiar with cross-cultural adaptation. The final version (Supplementary Table 1) was, with the approval of the Expert Committee, preliminarily administered to patients with SSc attending the hospital. After patients answered, each question was discussed with them to check whether all items had been fully understood.

Study instruments

The UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 is a 34-item questionnaire with seven subscales (reflux, distension/bloating, fecal soilage, diarrhea, social functioning, emotional well-being, and constipation). Each item scores the frequency of symptoms over a recall period of 7 days from 0 to 3, where 0 indicates no GI problems and three indicates worse health. The exceptions are questions 15 (diarrhea subscale) and 31 (constipation subscale), which are scored from 0 (no matter) to 1 (worse health). The score of six subscales (excluding constipation) is summed as the total score, which captures the overall burden of disease (the possible scores range from 0 to 2.83).

The Short Form Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2) is the most widely used measurement of general health and QoL [24]. It is based on norm-based scoring algorithms standardized by the same average (i.e., 50) and the same standard deviation. The survey has eight aspects: physical functioning (PF), physical role (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social role functioning (SF), emotional role functioning (RE), and mental health (MH). The physical (PCS) and mental component scores (MCS) are calculated based on those aspects; higher scores indicate a higher QoL [25].

The EQ-5D questionnaire is one of the most widely used instruments for measuring utility, and is available in several languages including Korean [26]. It consists of five health dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. The questionnaire also comprises a visual analogue scale domain, which measures the overall HRQoL on a scale of 0 (worst health state) to 100 (best health state).

Statistical analysis

The reliability of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 was assessed by the test–retest method at a 1-week interval in all 37 patients. This yielded an estimate of the instrument’s reproducibility over time as measured by intraclass correlation (ICC). The test–retest reliabilities were interpreted as appropriate if the ICCs were > 0.7 and 0.9 for group and individual comparisons, respectively.

Internal consistency was evaluated using the Cronbach’s α method for the seven subscales and the total score of the Korean version of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 questionnaire. A Cronbach’s α coefficient > 0.7 indicates a good correlation. Floor and ceiling effects were defined as the proportion of patients with the minimum (floor, representing absence of symptoms) and maximum (ceiling, representing the worst symptoms) possible scores. These proportions were calculated for each scale and an effect was considered present if more than 15% of patients had the maximum or minimum score. We assessed the construct validity of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 questionnaire by examining its correlations with the SF-36v2 and EQ-5D scales by Spearman correlation [8–10,12]. Correlations (rho) ≤ 0.29 were considered small, 0.30 to 0.49 were moderate, and those ≥ 0.50 were considered large. SPSS version 26.0 software (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and categorical variables were assessed using the chi-square or Fisher exact tests. Simple relationships were assessed using Spearman rank-correlation analyses. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Patients

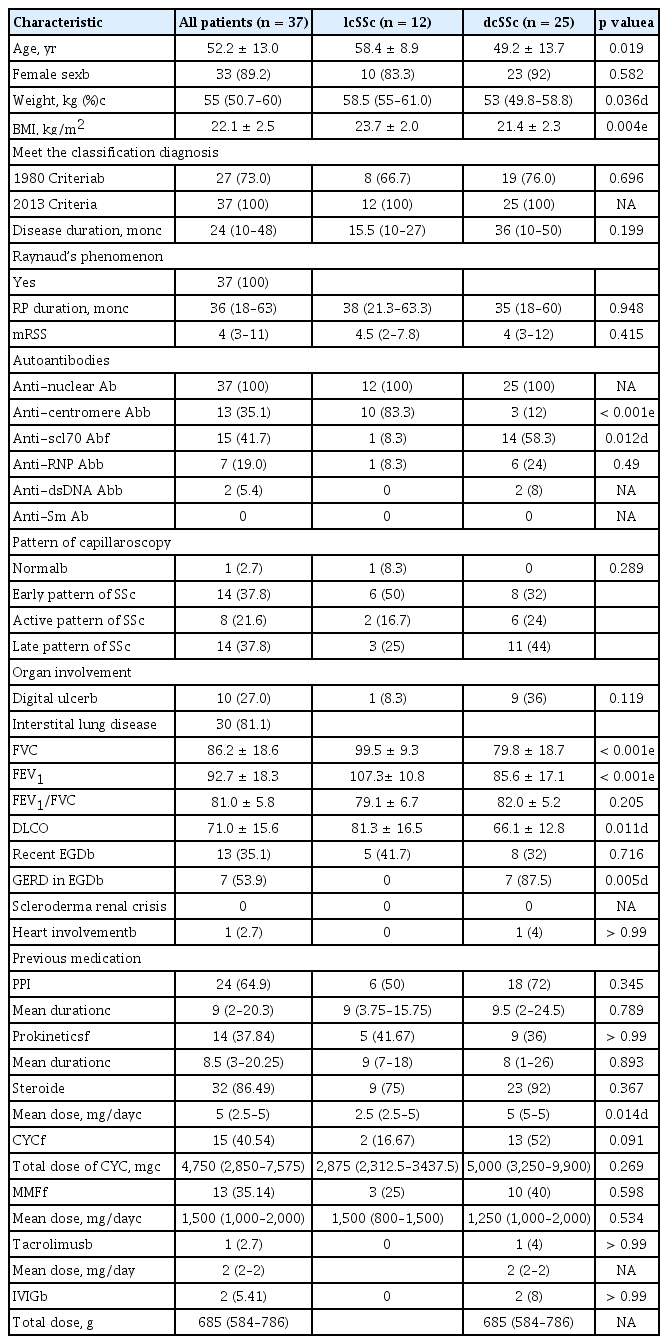

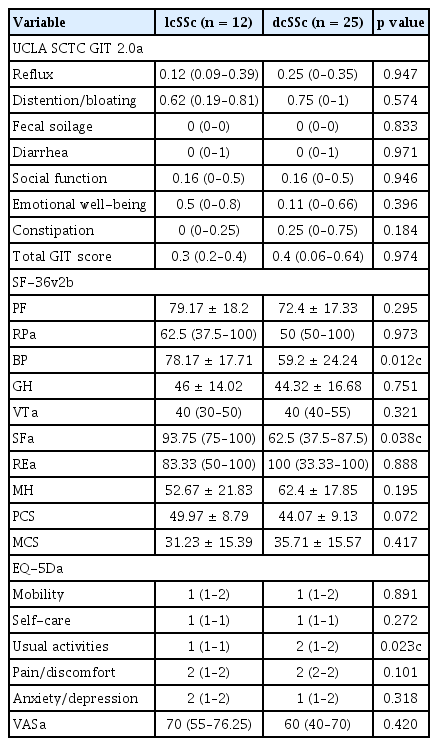

Patients with an incomplete clinical assessment were excluded from the analyses. Complete data were available for 37 patients (12 lcSSc and 25 dcSSc) with consecutive scheduled study instruments. Those patients’ characteristics are listed in Table 1. Most of the patients with SSc (n = 37) were women (89.19%), and they had a mean age of 52.2 years, BMI of 22.1 kg/m2, median disease duration (interquartile range [IQR]) of 24 months, and median mRSS of 4 points. The lcSSc subtype was diagnosed in 12 patients (32.4%) and the dcSSc was documented in 25 (67.6%). The patients with dcSSc were more frequently anti-Scl70 positive; had higher GERD on EGD, and had lower FVC, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), and DLCO than those with lcSSc. The HRQoL instruments in patients with SSc are shown in Table 2. The median total GIT score was 0.3 and did not differ between the lcSSc and dcSSc subtypes.

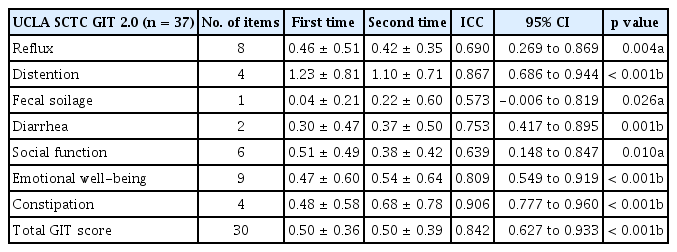

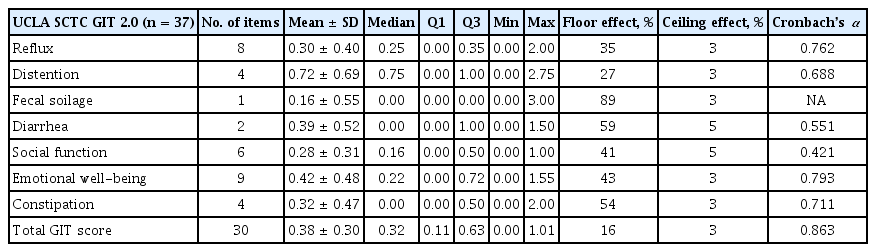

Reliability and internal consistency

The Korean UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 questionnaire showed good and reproducible reliability; the ICC values were close to 0.7 and statistically significant for all subscales (Table 3). For most subscales, Cronbach’s α was ≥ 0.7; the exceptions were the diarrhea and social function subscales (Cronbach’s α = 0.551, α = 0.421), suggesting good internal consistency. There was floor effect for both the scale itself and all of the subscales, ranging from 16% (total GIT score) to 89% (fecal soilage); however, there was no ceiling effect (Table 4).

To assess construct validity, the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 was compared to the SF-36v2 and EQ-5D. The reflux domain of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 was moderately correlated with the SF-36v2 (PF, RP, BP, VT, SF, RE, MH, and MCS). The emotional well-being domain of the was negatively correlated with that of the SF-36v2, except the PCS. The total GIT score of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 was negatively correlated with that of the SF-36v2, except RP, BP, and GH (Table 5). However, most domains of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 were not correlated with those of the EQ-5D. The emotional well-being domain was significantly correlated with that of the EQ-5D, except usual activities and pain. The total GIT score of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 was significantly correlated with that of the self-care domain of the EQ-5D (rho = 0.385, p = 0.019) (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

The UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 of Khanna et al. [5] was the first validated 34-item questionnaire for assessing GIT involvement. The total score is the average of six of the seven subscales (excluding constipation), and the 2.0 version was developed using 52 items from the SSc-GIT 1.0 and 1 rectal incontinence item, grouped into the reflux, distention/bloating, diarrhea, fecal soilage (rectal incontinence), constipation, pain, emotional well-being, and social functioning scales. Version 2.0 includes 34 items and is scored from 0 to 3, with lower values indicating a better HRQoL. The measures have been validated in terms of manometry and for esophageal and gastric transit time [4].

Almost 90% of patients with SSc suffer from GIT symptoms, which include malabsorption, GERD, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. GIT symptoms are diagnosed by specific tests and can manifest as various degrees of severity and from the mouth to the anus in SSc patients [1]. These symptoms, if severe, can impose a large burden in terms of mortality, morbidity, and HRQoL [27]; thus, insightful assessments are necessary. The frequency of GIT involvement in patients with SSc is reportedly 2% to 95%; the wide range is likely due to different studies using different diagnostic tools [28]. A physical examination for GIT manifestations can be less specific than for other organs. The present HRM and EGD provide insight into the perception of GIT symptoms and may improve the clinical management of patients with SSc with neither dysmotility nor erosive esophagitis. However, some aspects are insufficient to reflect the symptoms or evaluate the response to treatment. Patient questionnaires can help to establish a more patient-oriented approach and assess the social and psychological contribution to symptoms; therefore, they are an important aspect of clinical decision making [29,30]. The importance of PROs is emphasized by the increasing frequency of assessment of GIT involvement in clinical trials. PROs have the advantages that the questionnaire does not require the time of a physician and can be completed by the patient and returned by mail without the patient attending the hospital. The UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 instrument can be used to determine a PROs in randomized controlled trials of SSc-associated GIT involvement [5,31]. Self-reported GI QoL tools may be specific for issues related to SSc and could be used to monitor changes over time or during a trial.

The English-language version of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 has been validated in Western cohorts in the US and Canada and has been adapted for use in a number of European countries. The overall burden of GIT symptoms markedly differs by country. East Asian patients with SSc have a lower frequency of erosive esophagitis, dysmotility, and GERD compared with Western patients [32]. Recent HRM studies of Western patients with SSc have demonstrated diverse esophageal motility patterns, with absent contractility being the most prevalent. It is plausible that underlying ethnic differences affect the prevalence of erosive esophagitis; these may include differences in the frequency of Helicobacter pylori infection, gastric acid secretion, dietary habit, obesity prevalence, and unspecified genetic factors that predispose to erosive esophagitis [33]. The difference is a fundamental problem that requires a trans-cultural adaptation and validation process, particularly in East Asia. Our findings show that the Korean UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 questionnaire has good internal consistency and test–retest reliability indicating generally acceptable construct validity with SF-36v2 and EQ-5D. Our enrolled patients had a shorter median disease duration (24 months) and lower skin-hardening score (mRSS) than those of other similar studies. For this reason, our patients had a low total GIT score and few complaints of digestive symptoms. In further studies, longitudinal follow-up of patients is needed to monitor development of severe skin and involvement of other organs, including the GIT. Moreover, to apply the Korean UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 instrument in real-world settings, it is necessary to match the HRM, EGD, and esophageal/gastric transit time in patients with SSc.

In conclusion, the Korean translation of the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 instrument has good test–retest reliability and could support a novel PROs GIT assessment for research and routine practice in Korean patients with SSc.

KEY MESSAGE

1. The Korean version of the University of California–Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium Gastrointestinal Tract (UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0) questionnaire showed good and reproducible reliability.

2. In clinical trials, the UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 can be used to assess gastrointestinal tract (GIT) involvement in systemic sclerosis (SSc) in Korean patients.

Notes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Inwon Kim (Department of Mathematics, University of California, Los Angeles) and Prof. Haegeun Chung (Department of Environmental Engineering, Konkuk University) for the forward and backward translation of the instrument.

This study was supported by the Korean Association of Internal Medicine and Soonchunhyang University.