Current trends in the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms in Korea: a national survey

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

The study aimed to investigate the current practice patterns in the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms in Korea.

Methods

An electronic survey was systematically distributed by email to members of the Korean Pancreatobiliary Association from December 2019 to February 2020.

Results

In total, 115 (110 gastroenterologists, five surgeons) completed the survey, 72.2% of whom worked in a tertiary/academic medical center. Most (65.2%) followed the 2012/2017 International Association of Pancreatology guidelines for the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms. A gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography was the most common first-line diagnostic modality (42.1%), but a contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan was preferred as a subsequent surveillance tool (58.3%). Seventy-four percent of respondents routinely performed endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for pancreatic cystic neoplasms with suspicious mural nodules. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology (94.8%) and cystic fluid carcinoembryonic antigen (95.7%) were used for cystic fluid analysis. Most (94%) typically recommended surgery in patients with high-risk stigmata, but 18.3% also considered proceeding with surgery in patients with worrisome features. Most (96.5%) would continue surveillance of pancreatic cystic neoplasms for more than 5 years.

Conclusions

According to this survey, there was variability in the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms among the respondents. These results suggest that the development of evidence-based guidelines for pancreatic cystic neoplasms that fit the Korean practice is needed to create an optimal approach to the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs) are recognized, ranging from 2.6% to 15% in general populations, due to the increased use of high-quality imaging modalities in clinical practice [1,2]. PCNs are a heterogeneous group of disorders with a wide range of benign, borderline, or malignant pathologic features [3]. Most PCNs have a relatively indolent course, but others should be resected due to the risk of malignant transformation [4]. Despite considerable investigations, their actual biological behavior or natural history remains unclear. Furthermore, accurate selection of patients with PCNs for surveillance versus operative management remains difficult, and the accuracy of preoperative PCN classification comparing post-operative diagnosis may be suboptimal [5]. Regarding these uncertainties, even though malignant transformation is very rare, PCNs may present significant challenges and anxiety for both the patients and the healthcare providers.

Practice guidelines for PCNs have been recommended to ensure standardized surveillance and treatment strategies. Such guidelines were issued in 2017 by the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP), and, more recently, in 2018, at the United States of America and Europe [4,6,7]. However, these guidelines contain recommendations, including expert opinions, based on relatively low-level evidence and on retrospective studies that consider only surgically treated patients. Moreover, several aspects on treatment and surveillance strategies differ among the guidelines. Therefore, it is thought that the management of patients with PCN in real clinical practice may vary depending on clinicians’ guideline preference, experience, or type of hospital. To date, there have been few studies about the practical management of PCNs. This nationwide study aimed to investigate the current practice patterns in the management of PCNs in Korea.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This study was based on a nationwide electronic survey conducted from December 2019 to February 2020. The survey was distributed by email and administered through a web-based survey platform (SurveyMonkey, San Mateo, CA, USA). Potential participants were identified using the database from the Korean Pancreatobiliary Association (KPBA). Survey participants were informed that the survey required 5 to 10 minutes to complete. During the study period, reminder emails were sent every week for participants. All completed data were anonymized and analyzed using a web-based software platform.

Survey creation and electronic survey contents

The current validity of the survey was determined through the literature review and was based on the reviews of expert members of Policy-Quality management in KPBA. The final survey was a 20-item questionnaire (Appendix 1). The survey items included baseline characteristics regarding age, gender, subspecialty, and type of hospital. Clinicians’ preferred guidelines, clinical application of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), practice patterns regarding the choice of imaging modalities, interval of surveillance, and the criteria for surgical resection were also included. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Wonkwang University Hospital (IRB No. WKUH 2020-06-019-001). In accordance with IRB guidelines for anonymous surveys, the need for documentation of informed consent among participants was waived.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were reported as mean ± standard deviation, and proportion. A Student’s t test was used for comparison of continuous data, and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of categorical variables. A p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

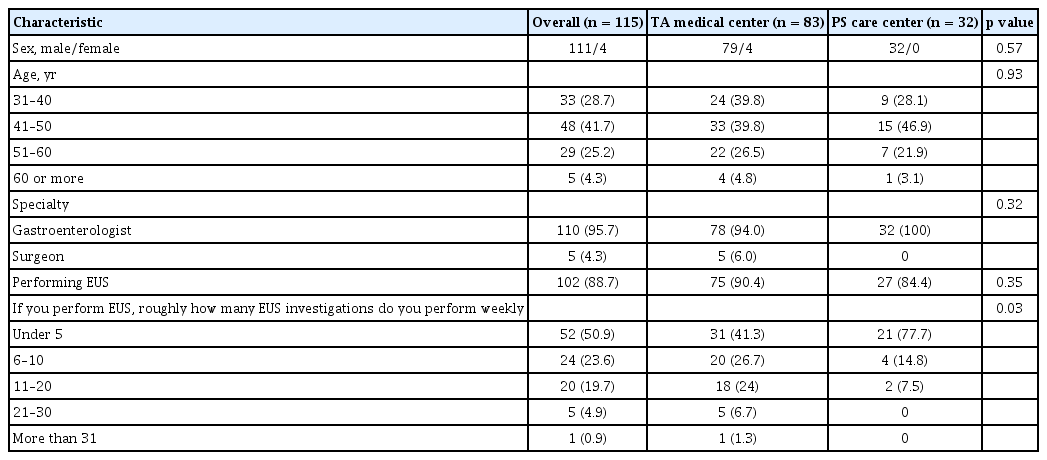

Baseline characteristics

The survey was distributed to 1,010 email addresses through the KPBA membership directory, and 115 (11.4%) were completed. We excluded 25 (2.4%) that were partially completed. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. The majority of respondents were male (96.5%), gastroenterologists (95.7%), working in a tertiary/academic (TA) medical center (72.2%), and performing EUS (88.7%). Compared to the respondents from the TA medical center, fewer respondents from primary/secondary (PS) care centers were performing more than six examinations of EUS a week (53% vs. 18.8%, respectively; p = 0.03). The respondents reported that the patients with PCNs who were referred to the hospital were mostly identified by contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) (57.4%) or by trans-abdominal ultrasound (38.2%). Most practitioners (65.2%) followed the 2012/2017 IAP guidelines for the management of PCNs. There was no significant difference in preferred practice guidelines between practitioners at the TA medical center and at the PS care center (p = 0.67) (Fig. 1).

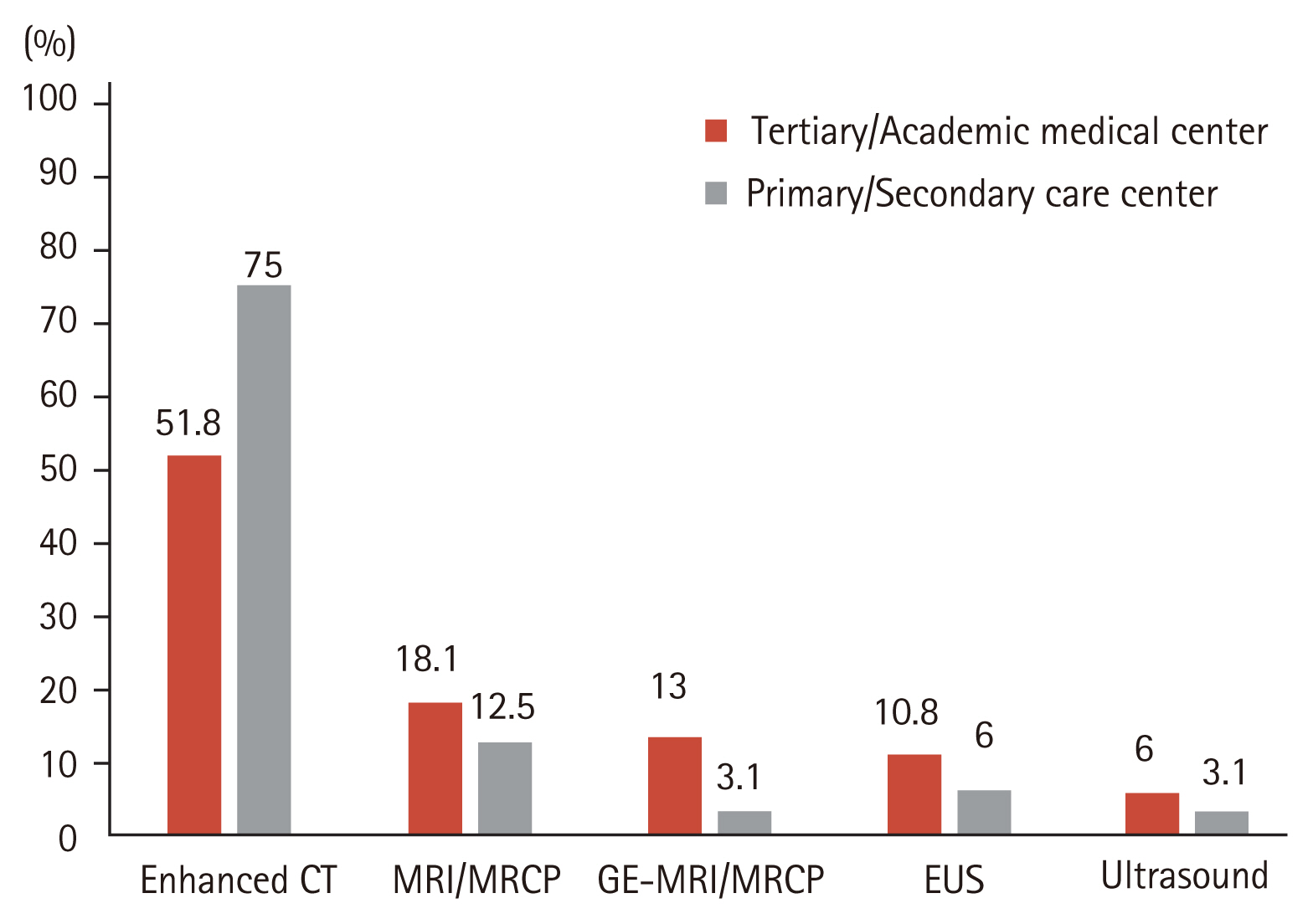

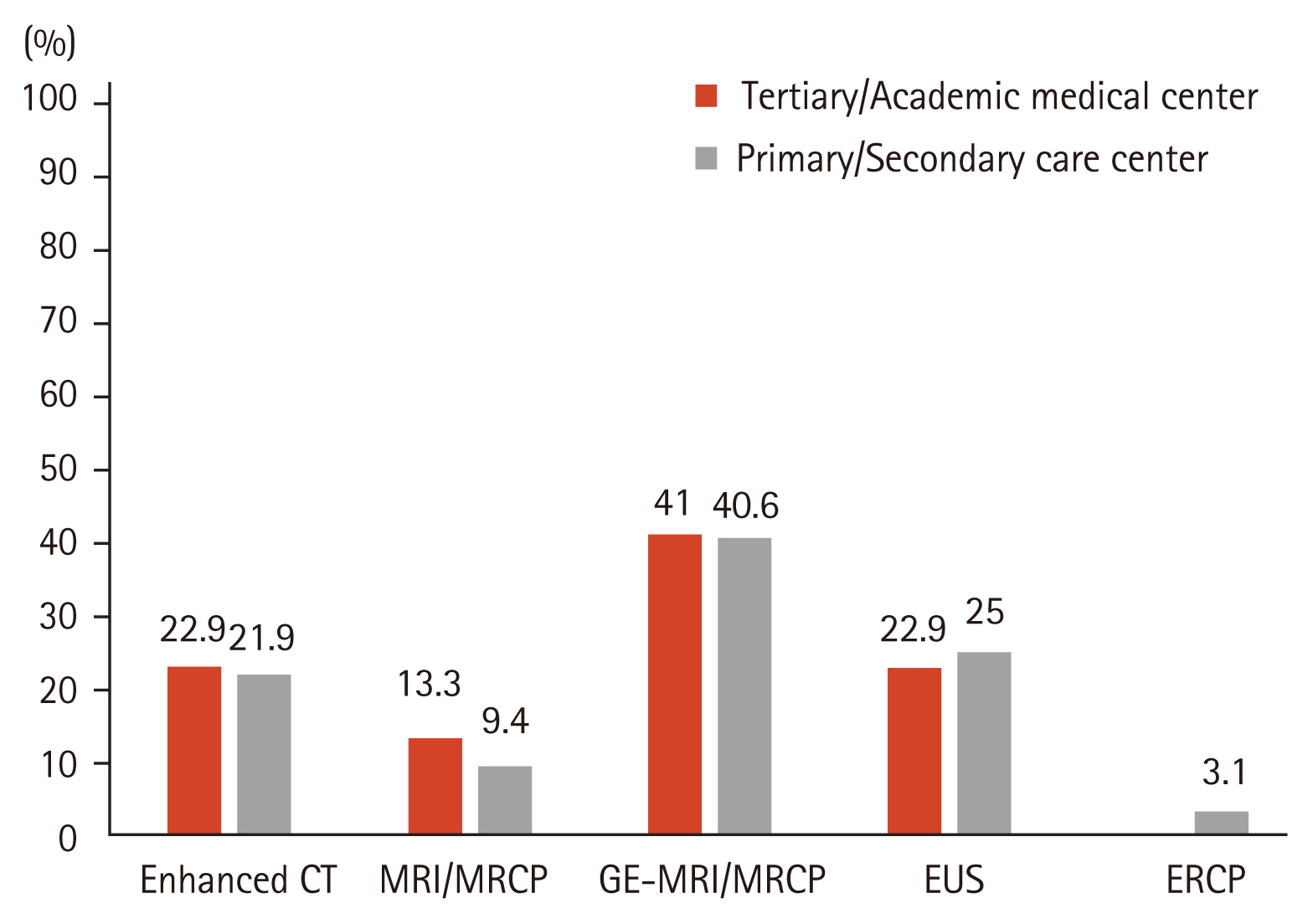

Imaging modalities

For the initial work-up of PCNs, a gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (GE-MRI/MRCP) (40.9%) was preferred over non-enhanced MRI/MRCP (12.2%), CE-CT (22.6%), EUS (23.5%), or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (0.9%) (Fig. 2). Regarding the follow-up modalities, however, 58.3% of the respondents mainly used CE-CT over other imaging studies, regardless of hospital type (Fig. 3).

Preferred imaging modalities for initial work-up of pancreatic cystic neoplasms. CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; GE-MRI, gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde choangiopancreatography.

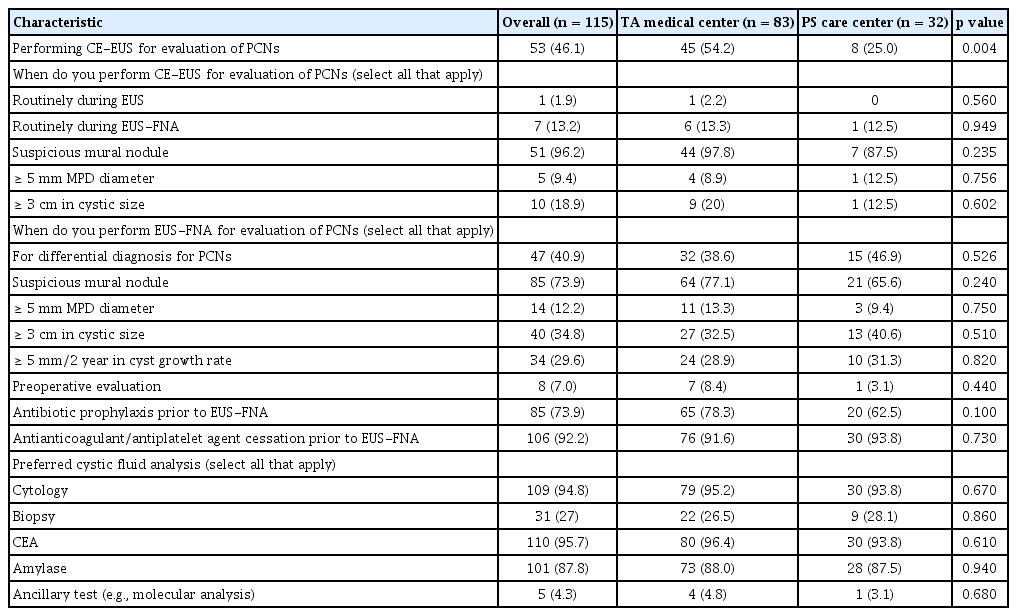

Contrast-enhanced EUS and EUS-guided fine needle aspiration

Fifty-three respondents reported using contrast-enhanced EUS (CE-EUS) for evaluation of PCNs, especially in cases of suspicious mural nodules. TA medical respondents significantly favored using CE-EUS compared with respondents from the PS care center (54.2% vs. 25%, respectively; p = 0.004). A large proportion of both groups (77.1%, TA medical center vs. 65.6%, PS care center) indicated that they performed EUS-fine needle aspiration (FNA) for PCNs with suspicious mural nodules. Nearly all subjects routinely checked for cystic fluid carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (95.7%) followed by cytology (94.8%). Most reported that prophylactic antibiotic administration (73.9%) and cessation of anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents (92.2%) prior to the EUS-FNA was implemented (Table 2). In total, 20 respondents experienced EUS-FNA-related adverse events including bleeding (n = 6), pancreatitis (n = 6), infection (n = 2), abdominal pain due to pancreatic juice leakage (n = 3), and perforation (n = 3).

Surveillance and surgical referral patterns

The surveillance strategies and surgical referral patterns are shown in Table 3. Regarding 2 to 3 cm sized PCNs, most respondents suggested a surveillance interval of 6 months (66.1%); the remainder chose 3 months (29.6%), or 1 year (4.3%). In cases of PCN with main pancreatic duct (MPD) dilation (5 to 9 mm), most (80%) followed up at 6-monthly intervals. The 81.7% of the respondents would refer a patient to surgery for a PCN with high-risk stigmata. A larger proportion of the respondents from PS care center recommended surgery even if the PCNs had worrisome features (18.3%, TA medical center vs. 31.2%, PS care center, p = 0.03). Most respondents (96.5%) would continue surveillance of PCNs for more than 5 years. Guidelines for the surveillance interval in PCNs with cysts sized 2 to 3 cm, or with MPD dilation of 5 to 9 mm are shown in Table 4. Of those who followed the 2012/2017 IAP guidelines, the 2018 American College Gastroenterology (ACG) clinical guideline, or the 2018 European guidelines, adherent to PCN with 2 to 3 cm or MPD dilation (5 to 9 mm) was 94.6%, 90.9%, and 100%, or 90.6%, 86.3%, and 72.2%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

As the prevalence of PCNs increased, several groups published their guidelines for management of PCNs. These guidelines are similar in many respects but considerable differences exist, including surveillance strategies and additional interventions. In our survey, most respondents followed the 2012/2017 IAP guidelines to manage the patients with PCNs, regardless of subspecialty or type of hospital. Most PCNs were initially identified by CE-CT (57.4%) or by trans-abdominal ultrasound (38.3%). A GE-MRI/MRCP (40.9%) was mainly used as a diagnostic imaging modality for better characterization of PCNs. However, the question on subsequent follow-up imaging modalities indicated that a CE-CT (58.3%) was used most commonly. Westerveld et al. [8] evaluated the practice pattern for the evaluation and management of incidental pancreatic cysts on survey. The author reported that MRI was the preferred modality for PCNs surveillance in most respondents (83.1%). In a different survey, assessing the approach of Dutch gastroenterologists in the management of asymptomatic PCNs, Hol et al. [9] found that EUS (39% and 57%) was considered as more a sensitive surveillance technique than CT (19% and 13%) or MRI/MRCP (22% and 22%) when evaluating 10 and 25 mm PCNs.

Most guidelines recommend the use of MRI/MRCP as an imaging tool for diagnosis and surveillance, primarily because of their non-invasiveness, lack of exposure to radiation, and greater sensitivity for identifying communication between the cyst and the pancreatic duct system. In contrast to the recommendations from several guidelines, a CE-CT was preferred as a subsequent follow-up imaging modality in this survey. Although the reason for their choice was not questioned in the survey, these findings may result from considering the economic burden. The national health insurance system in Korea was changed in November 2019 to cover MRCP assessments for PCNs. GE-MRCP or MRCP is expected to be increasingly used as preferred follow-up imaging modality for PCNs in Korea.

The presence of mural nodules in PCNs is considered as high-risk stigmata by the IAP guidelines. However, it may be difficult to determine whether mural nodule-like lesions are true mural nodules or mucus plugs. A CE-EUS allows to distinguish a true mural nodule from a mucus plug by identifying the microvasculature within the lesions [10–12]. Thus, a CE-EUS can identify the target lesion for EUS-FNA and avoid unnecessary puncture of the mucus plug. The recent guidelines have also recommended a CE-EUS for further evaluation of mural nodules in PCNs [4,6,7]. However, a CE-EUS remains unable to differentiate between serous and mucinous PCNs, due to similarity of enhancement patterns, including in the cystic walls and the septum [11,13]. In our survey, TA medical respondents used CE-EUS significantly more often than PS care center respondents (54.2% vs. 25%, respectively; p = 0.004). This result may be attributable to some PS care centers, not having CE-EUS-enabled equipment and the high cost of CE-EUS. The clear indication or superiority of CE-EUS for the evaluation PCNs have not yet been established to date. In addition, there is a lack of appropriate education program on CE-EUS. Therefore, further studies and education programs on CE-EUS are needed.

EUS-FNA can differentiate between mucinous and non-mucinous cysts and between malignant and benign lesions. Evaluation techniques of aspiration cystic fluid, including color, viscosity, intra-cystic CEA, and cytology, are widely used to evaluate PCNs. In particular, the diagnostic yield of cytology for PCNs with suspicious mural nodules or masses are reported to be up to 89.6% [14]. However, the sensitivity of cystic fluid cytology is relatively low in the case of PCNs without mural nodules, and consensus on the cutoff level of cystic fluid CEA for differentiating mucinous from non-mucinous cysts has not yet been achieved [15]. To overcome these problems, various devices or novel techniques have been investigated, but more research is needed to elucidate a gold standard method [16]. Our findings showed that most respondents analyzed the EUS-FNA cytology and intra-cystic CEA levels for cystic fluid analysis, as in many studies. Other techniques or methods, including molecular markers, are not commonly used in real-world practice [17].

There is no strict indication for EUS-FNA in PCNs. Westerveld et al. [8] reported that about half of the participants in the PCNs management survey would routinely perform EUS-FNA for the evaluation of PCNs without a mural nodule, solid component, or MPD dilation. The indications of EUS-FNA may vary slightly, depending on the guidelines. In particular, guidelines differ regarding the use of EUS-FNA for high-risk lesions, such as those with mural nodules. American and European guidelines support EUS-FNA in lesions appearing to be high-risk. However, the IAP guidelines recommend surgical management of high-risk lesions without EUS-FNA, because of possible peritoneal seeding from the leakage of fluid contents by EUS-FNA [18,19]. From this survey, many respondents followed the IAP guidelines, but, contrary to the guideline recommendations, most of the EUS-FNA for PCNs were performed in cases of suspicious mural nodules in current practice. Explanations for this discrepancy may be as follows (1) these procedures rarely lead to EUS-FNA related tumor dissemination in subsequent studies (2) difficulties in determining surgery without pathologic evaluation (3) [19,20]. Furthermore, the performance of EUS-FNA may vary by PCN location, but the current study did not include this factor.

The major concern of EUS-FNA for PCNs is procedure-related adverse events. In a large prospective study, the overall rate of EUS-FNA-related adverse events was 6% [21]. The most common adverse event was bleeding (2.35%), followed by infection (1.34%), and pancreatitis (0.67%). Administration of prophylactic antibiotics, and discontinuation of anticoagulant/antiplatelet drugs after tailored thrombotic risk assessment, are recommended in most guidelines to reduce the risk of bleeding or infection, although conclusive evidence is lacking [4,22,23]. In our survey, 20 respondents experienced EUS-FNA-related adverse events including bleeding, pancreatitis, infection, abdominal pain due to pancreatic juice leakage, and perforation. Prophylactic antibiotic administration and cessation of anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents prior to the EUS-FNA were generally performed in our survey.

The current survey showed relatively high rates of guideline adherence for the surveillance interval in PCNs with cysts sized 2 to 3 cm or with MPD dilation (5 to 9 mm). However, our findings differed from those of previous studies. Schenck et al. [24] evaluated the guideline adherence to major published guidelines on PCNs. Of those who received surveillance, only 66% were monitored with minimally appropriate follow-up per any guideline. Therefore, authors concluded that adherence to guideline surveillance for PCNs was poor. Tabrizian et al. [25] also demonstrated poor compliance with clinical guidelines for management of IPMNs in real practice. In real-world practice, besides considering guidelines, decision-making about treatment and surveillance strategies for PCNs consider various factors including age, comorbidities, location of the lesion, and socioeconomic status. Therefore, management for PCNs can make it difficult to follow the guidelines, even if clinicians attempt to adhere. In the current study, our survey questionnaires for surveillance interval included cyst size or MPD diameter but no other clinical factors such as life expectancy, cyst location, or comorbidities. For these reasons, there may be a difference between the healthcare provider-based current survey results and patient-based clinical researches.

Differences in clinical practice between TA medical respondents and those from PS care centers existed in the surgical referral pattern. Our findings demonstrated that TA medical respondents were significantly less likely to recommend surgery in the case of worrisome features than were respondents from PS care centers (18.3% vs. 31.2%, respectively; p = 0.03). In clinical practice, pancreatic surgery is rarely performed in PS care centers because of its significant morbidity and mortality, and a lack of surgical staff. In addition, compared to TA medical centers, PS care centers have insufficient medical staff and equipment to enable additional tests including EUS, CE-EUS, or EUS-FNA for evaluating PCNs with worrisome features. These real points can make it difficult for the respondents from PS care centers to perform regular surveillance for patients with PCNs with malignant potential, such as those with worrisome features. Thus, many patients with PCNs with worrisome features in PS care centers may be transferred to TA medical centers for second opinion, which may lead to surgery. Furthermore, TA medical practitioners may have more expertise with EUS, greater experience, and better knowledge of PCNs. It is assumed that these practical issues caused some difference in the surgical referral pattern between the two groups.

In the current survey, five surgeons participated and no significant differences including preferred guidelines, surveillance strategies, and surgical referral patterns for the management of PCNs were found between the gastroenterologist and surgeon (Supplementary Table 1). These findings may reflect the bridging of the gap between two groups in the management of PCNs. However, it is difficult to fully accept these results because there were limitations associated with the statistical analyses including the small sample size and the fact that different results might have been obtained if more surgeons had participated.

Practice patterns for the management of PCNs, especially in the intensity of surveillance or surgical referral pattern, may be affected by the age of the practitioners. In the present study, in comparison with old practitioners (> 50 years), there was no significant difference in other practice patterns; however, younger practitioners (31 to 50 years) observed PCNs with cysts sized 2 to 3 cm or with MPD dilation (5 to 9 mm) in shorter intervals (Supplementary Table 2). These results may reflect the difference in the level of experience. Another possible explanation is that younger practitioners tend to be more concern about malignant transformation of PCNs due to the paucity of well-established guidelines.

To date, studies on practice patterns related to the management of PCNs are limited. This is the first national survey in Korea to assess the actual clinical patterns for management of PCNs. However, several limitations still exist. First, the survey was restricted to the members of KPBA, thereby introducing selection bias in our cohort. Therefore, the generalizability of our survey results to practice patterns in other country is uncertain. Second, the response rate was suboptimal, and thus a response bias may occur. The potential distortion of the survey outcomes may exist in the absence of analyzable data for non-respondents. Third, recall and reporting bias may occur, as in other all surveys.

In conclusion, this study identified differences in PCN management among the respondents. In addition, some aspects in a real clinical setting vary considerably from the recommendations of existing guidelines. Therefore, evidence-based guidelines for PCNs that fit the Korean practice are needed to establish an optimal approach to the management of PCNs.

KEY MESSAGE

1. Clinicians’ management strategies of pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs) slightly vary according to their preferred guideline, experience, or type of hospital in Korea.

2. Korean clinician showed relatively high rates of PCNs guideline adherence, but there were several differences between real clinical practice and the recommendations of existing guidelines.

3. Continuous efforts to develop the evidenced- based guidelines for PCNs that fit the Korean practice are needed.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

We thank all respondents of this study and Policy-Quality management members of the Korean Pancreatobiliary Association and study personal for their contribution to the study.