Mycobacterium avium lung disease combined with a bronchogenic cyst in an immunocompetent young adult

Article information

Abstract

We report a very rare case of a bronchogenic cyst combined with nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease in an immunocompetent patient. A 21-year-old male was referred to our institution because of a cough, fever, and worsening of abnormalities on his chest radiograph, despite anti-tuberculosis treatment. Computed tomography of the chest showed a large multi-cystic mass over the right-upper lobe. Pathological examination of the excised lobe showed a bronchogenic cyst combined with a destructive cavitary lesion with granulomatous inflammation. Microbiological culture of sputum and lung tissue yielded Mycobacterium avium. The patient was administered anti-mycobacterial treatment that included clarithromycin.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex is the most frequently encountered cause of lung disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) [1]. NTM lung disease is common in structural lung disease, such as chronic obstructive lung disease, bronchiectasis, and prior tuberculosis. Here, we describe a bronchogenic cyst combined with M. avium lung disease in an immunocompetent young adult patient.

CASE REPORT

A 21-year-old male was referred to our hospital because of a cough, fever, and progressive lung lesion on his chest radiograph. He was a non-smoker. A cystic mass had been noticed on the chest radiograph at a routine health check 6 months earlier (Fig. 1A). He was given a presumptive diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis without bacteriologic confirmation. The patient had been taking anti-tuberculosis medication for 6 months. However, the mass increased in size (Fig. 1B) and new symptoms developed, such as the cough and fever. Consequently, he was referred to our hospital.

A 21-year-old man with Mycobacterium avium infection combined with a bronchogenic cyst. (A) Chest radiography showed a cystic mass in the right upper lobe. (B) After anti-tuberculosis medication for 6 months, the mass increased in size and developed multiple cavities.

On admission, his body temperature was 39℃. His white blood cell count was 8,460/µL, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 74 mm/hr, and C-reactive protein increased to 5.39 mg/dL. A human immunodeficiency virus antibody test was negative. A chest radiograph and computed tomography revealed a huge, multi-septated cystic mass in the right upper lobe (Fig. 2A).

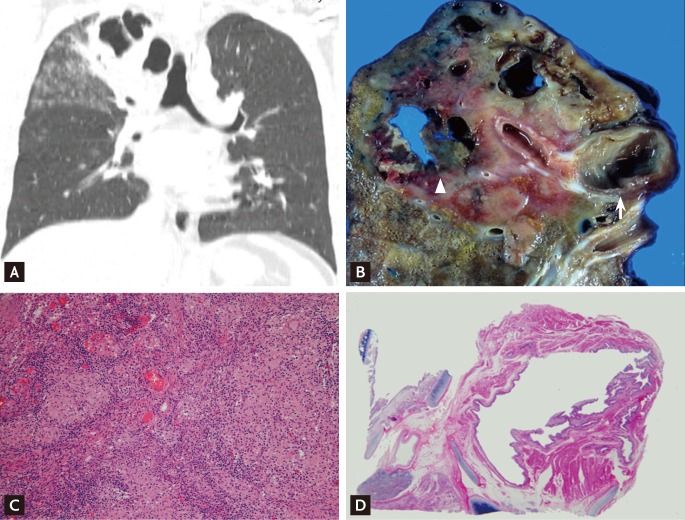

A 21-year-old man with Mycobacterium avium infection combined with a bronchogenic cyst. (A) Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed a multi-loculated cystic mass with bronchiolitis in the right upper lobe. (B) The resected right upper lobe showed an intrapulmonary bronchogenic cyst in the apical segment (arrow) and multiple cavitary necroses in the destroyed apical segment of the right upper lobe (arrowhead). (C) Microscopic findings of the multiple cavitary lesions revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation (the lesion is indicated by an arrowhead on the chest CT and gross findings) (H&E, × 100). (D) The microscopic findings of the bronchogenic cyst showed that the cyst was walled by ciliated columnar epithelium (the lesion is indicated by an arrow on chest CT and gross findings) (H&E, × 40).

Numerous acid-fast bacilli (AFB) were seen in multiple sputum specimens. However, nucleic acid amplification tests for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the sputum specimens were negative using a commercial DNA probe (Gen-Probe amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct test, Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA, USA). The results of both a tuberculin skin test and serum interferon gamma assay (QuantiFERON-TB Gold, Cellestis, Victoria, Australia) were negative. A polymerase chain reaction method used to examine AFB-positive sputum specimens was for identification of the causative agent [2]. The result was positive for M. avium.

Based on the clinical findings and laboratory data, our diagnosis was M. avium infection combined with congenital cystic lung disease. The antibiotic therapy was changed to clarithromycin (1,000 mg/day), rifampicin (600 mg/day), ethambutol (800 mg/day), and streptomycin (1 g intramuscularly three times per week).

The patient underwent a right upper lobectomy 3 weeks later for confirmative diagnosis and treatment of complicated congenital cystic lesion. The resected lung contained a 2.5 × 2 cm intrapulmonary bronchogenic cyst and a 5 × 3.5 cm destructive cavitary lesion near the bronchogenic cyst in the right-upper lobe (Fig. 2B). Extensive granulomatous inflammation with caseous necrosis was found within the destructive cavitary lesion (Fig. 2C), and ciliated columnar epithelium without granuloma was found within the bronchogenic cyst (Fig. 2D).

Numerous mycobacterial colonies were cultured from multiple sputum specimens and excised lung tissue. All were subsequently identified as M. avium. The isolate was susceptible to clarithromycin. The patient's postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged without complications. He received postoperative antibiotic therapy for 6 months.

DISCUSSION

Bronchogenic cysts are the most common foregut cysts formed by abnormal detachment of the primitive foregut. The cyst wall often contains cartilage and respiratory epithelium. It rarely connects to the tracheobronchial tree. However, it may communicate with the tracheobronchial tree and become infected [3]. Although infection is a common complication of bronchogenic cysts, infection caused by mycobacteria is very rarely reported. In fact, bronchogenic cysts combined with NTM infection has been reported only once [4]. There were three additional cases in two reports of mycobacterial infection combined with a bronchogenic cyst [5,6]. However, M. tuberculosis was isolated from sputum in only one case, and no organisms were isolated in the other two cases.

In our case, M. avium lung disease existed adjacent to the bronchogenic cyst, and the clinical and radiologic findings could not differentiate it from an infected bronchogenic cyst, although the bronchogenic cyst was not actually infected with M. avium on pathologic evaluation. Lung disease due to NTM is common in structural lung disease, such as chronic obstructive lung disease, bronchiectasis, and prior tuberculosis [1]. However, whether M. avium infection in this case was a fortuitous association or a complication of the cyst itself is unclear.

In conclusion, we report a rare case of M. avium infection combined with a bronchogenic cyst in an immunocompetent young adult patient. M. avium-intracellulare complex infection should be added to the list of infectious complications of bronchogenic cysts.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.