Esophageal Thermal Injury by Hot Adlay Tea

Article information

Abstract

Reversible thermal injury to the esophagus as the result of drinking hot liquids has been reported to generate alternating white and red linear mucosal bands, somewhat reminiscent of a candy cane. This phenomenon is associated with chest pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, and epigastric pain.

Here, we report a case of thermal injury to the esophageal and oral cavity due to the drinking of hot tea, including odynophagia and dysphagia.

A 69-year-old man was referred due to a difficulty in swallowing which had begun a week prior to referral. The patient, at the time of admission, was unable to swallow even liquids. He had recently suffered from hiccups, and had consumed five cups of hot adlay tea one week prior to admission, as a folk remedy for the hiccups. Upon physical examination, the patient's oral cavity evidenced mucosal erosion, hyperemia, and mucosa covered by a whitish pseudomembrane. Nonspecific findings were detected on the laboratory and radiological exams. Upper endoscopy revealed diffuse hyperemia, and erosions with thick and whitish pseudomembraneous mucosa on the entire esophagus. The stomach and duodenum appeared normal. We diagnosed the patient with thermal esophageal injury inflicted by the hot tea. He was treated with pantoprazole, 40 mg/day, for 14 days, and evidenced significant clinical and endoscopic improvement.

INTRODUCTION

When a patient complains of dysphagia, odynophagia, and chest discomfort, the majority of clinicians approach a diagnosis by taking the patient's past history, determining any underlying diseases, and conducting an upper endoscopy coupled with histological exams. These symptoms are frequently induced by foreign bodies in the esophagus, infectious diseases such as candida, herpes, cytomegalovirus, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and malignant neoplasm, as well as other conditions. These diseases can be readily diagnosed via the careful acquisition of the patient's history, as well as an upper endoscopy with biopsy.

Here, we report a case of dysphagia, odynophagia, and chest discomfort, which was presumed to have been caused by thermal injury to the esophagus.

CASE REPORT

A 69-year old man visited our hospital, complaining of dysphagia, odynophagia, and chest discomfort. He reported that he had been treated at a local neurology clinic for Bell's palsy, which had developed ten days prior, and he had suffered from incurable hiccups sincethat time. Seven days prior to admission, the patient had experienced dysphagia, odynophagia, and chest discomfort, and thus was unable to consume anything except for water. With regard to the patient's past medical history, he was taking oral hypoglycemic agents and calcium channel blockers due to diabetes mellitus and essential hypertension. The patient denied GI symptoms indicative of gastroesophageal reflux or any history of medication causative of esophageal injury. Upon physical examination, the patient evidenced clear mentality and was deemed to be chronically ill. His blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, his pulse rate was 88beats/minute, and his body temperature was 37℃. We detected no specific findings on the patient's head and neck, chest, or abdomen. The results of the laboratory tests were as follows: WBC, 14,820/mm3 (normal: 3,800-10,500/mm3); Hb, 15.3 g/dL (13-18 g/dL); hematocrit, 42.1% (40.0-53.0%); platelet, 169,000/mm3 (130,000-450,000/mm3); AST/ALT, 21/16 IU/L (15-40/10-40 IU/L); total bilirubin, 1.3 mg/dL (0.1-1.2 mg/dL); total protein, 5.8 g/dL (6.4-8.3 g/dL); albumin, 3.3 g/dL (3.4-4.8 g/dL); alkaline phosphatase, 68 IU/L (25-100 IU/L); BUN/Cr, 23/1.1 mg/dL (6-20/0.9-1.3 mg/dL); glucose, 227 mg/dL (74-106 mg/dL); calcium, 8.0 mg/dL (8.1-10.4 mg/dL); phosphorus, 3.1 mg/dL (2.7-4.5 mg/dL); LDH, 376 IU/L (208-378 IU/L); PT, 13.8sec (11.6-15.5sec); aPTT, 33.1sec (28.0-45.0sec). Other laboratory tests were within normal ranges. The chest radiograph evidenced no active lung lesions, and we found no evidence indicative of ischemic heart disease on the electrocardiogram.

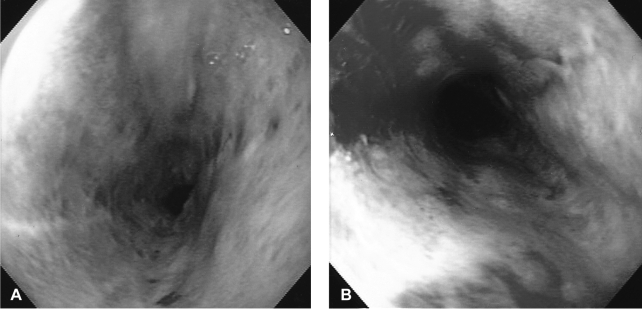

We conducted an upper endoscopy on the next day of admission. The results showed broad whitish plaques with multiple erosions on the oral mucosa, and also evidenced whitish plaques that nearly encircle the entire esophageal mucosa with erythema, spontaneous bleeding on the partially-exposed mucosal surfaces from the upper esophagus to the gastroesophageal junction. On the stomach, we observed some atrophic changes with partial erythema, but the results were otherwise nonspecific, and the duodenum revealed non-specific findings (Figure 1). There was no history or evidence of immune deficiency which would raise suspicions of infections including Candida, the Herpes virus, Cytomegalovirus, the Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, etc. The upper endoscopic findings themselves appeared more consistent with panesophagitis due to the ingestion of corrosive agents, and so we treated the patient with pantoprazole in order to prevent further injury from refluxed acid, and also instituted a parenteral nutrition regimen. After 3 days of that treatment the patient's symptoms gradually improved. During treatment, we re-questioned him as to whether he had previously ingested any corrosive agents, and his answer, although unexpected, was compelling. The patient reported drinking approximately five cups of hot adlay tea one week prior, as a folk remedy for the treatment of persistent hiccuping. The patient also reported that, at that time, he experienced a burning sensation within his oral cavity. However, the patient did not believe that this event was related to his symptoms, and so did not previously apprise us of the incident. We then concluded that the patient's symptoms and upper endoscopic findings were the consequence of esophageal thermal injury. We elected to continue the initial treatment, and the patient's symptoms improved rapidly. Follow-up endoscopy was conducted after 10 days of treatment. At that time, the oral mucosa were of normal appearance, and only linear whitish plaques, which had previously nearly encircled the entirety of the esophageal mucosa, remained. In the lower esophagus, we observed some whitish fibrotic scars, but we detected no stenotic changes (Figure 2). On the next day, the patient was discharged with no persisting symptoms.

Initial findings of esophageal endoscopy. (A) A thick whitish pseudomembranous patch that nearly encircles the entirety of the esophageal lumen. (B) Erythema with erosions and spontaneous bleeding from the injured esophageal mucosa.

DISCUSSION

Esophageal thermal injury is one of the diseases that can induce dysphagia, odynophagia, and chest discomfort. Other diseases, most notably pill-induced esophagitis, radiation injuries, infectious esophagitis from Candida, Herpes, or Cytomegalovirus, severe reflux esophagitis, and esophageal cancer, can cause similar symptoms. Until now, there have been approximately seven reports of esophageal thermal injury in the English literature, and the implicated caustic agents have included such substances as hot tea, other beverages, soup, hamburgers, lasagna, etc.1-5). The most characteristic upper endoscopic findings in such cases include alternating bands of whitish pseudomembraneous lesions, and linear erythema reminiscent of a 'candy cane'2). However, according to the report of Choi et al.1), these phenomena are actually characteristic of the healing stage after a certain time has passed after thermal injury. According to Choi, in cases in which the upper endoscopy is conducted a few days after the infliction of the thermal injury, a whitish pseudomembrane encircling the esophageal mucosa may be the predominant finding, rather than a 'candy cane appearance'. In other words, the endoscopic findings change over time, and thus if only the whitish pseudomembrane is detected, a detailed history should be acquired, keeping the possibility of esophageal thermal injury firmly in mind1). Actually, in some reports1, 2, 5) it has been asserted that, because some patients do not believe the actual causative event was, in fact, an important clue to the proper diagnosis of the disease, they fail to apprise their clinicians regarding previous ingestions of very hot meals, as was seen in this case. The events of this case suggest the possibility that many more cases of esophageal thermal injury may go unreported than are ever detected, not only in Korea but in many other countries as well.

According to the relevant reports1-5), the prognosis of esophageal thermal injury is generally favorable. After conservative anagement to prevent further thermal injuries or the administration of proton pump inhibitors, the majority of patients improved with regard to both clinical symptoms and endoscopic and histological characteristics, and severe complications, such as esophageal stenosis, have not been reported. Proton pump inhibitors are administered in order to prevent further injuries resulting from refluxed gastric acid3), and this was also implemented in the case presented herein.

However, in cases such as this, the possibility of esophageal cancer as a late complication of esophageal thermal injury should be considered. Munoz et al6) compared endoscopic precancerous lesions between a hot mate tea-drinking group and non-mate drinking group in Southern Brazil. Yioris et al7). compared cancerous lesions in the gastrointestinal tract via the combination of thermal injuries with exposure to the known carcinogen, N-Methyl-N'-Nitro-N-Nitrosoguanidine (MNNG). The common conclusion of these two studies is the inflammatory response, coupled with defects in the mucosal barrier after thermal injury renders the esophagus more susceptible to the activities of carcinogens. This indicates that esophageal carcinogenesis following thermal injury is a multifactorial process, dependent not only on physical damage, but also on the actions of a variety of risk factors, including alcohol, tobacco, etc6).

In conclusion, esophageal thermal injuries are frequently overlooked by clinicians. Thus, this disease should be considered in cases in which patients complaining of odynophagia, dysphagia, and chest discomfort are evaluated. Additionally, more diverse studies should be conducted regarding carcinogenesis of the esophagus following thermal injuries.