Sex differences in diagnosis and treatment of heart failure: toward precision medicine

Article information

Abstract

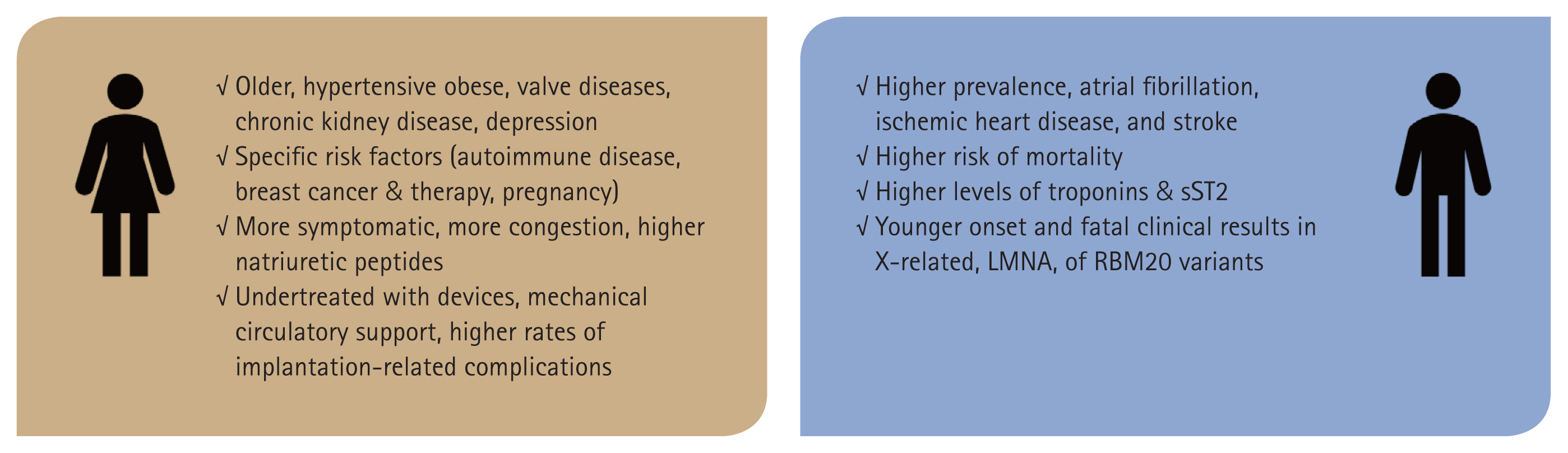

There are sex-related differences in the pathophysiology and phenotype of heart failure (HF) as well as the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs between women and men due to biological differences, such as heart and vessel size, response to blood volume and pressure, body water and muscle compositions, and dominant sex hormones. Therefore, target drug doses required to achieve the same clinical effect differ between the sexes, while there may also be sex-related differences in side effects of a given drug at the same dose. These biological differences have been reflected in the results of clinical trials. Moreover, women have been underrepresented in pharmacological therapy trials as well as having lower device implantation rates than men. Therefore, the currently recommended target doses of medications based on clinical trials may not be appropriate for women. Although guidelines for HF have been standardized since the last major revision in 2021, most do not differentiate by sex. This review focuses on evidence regarding sex-related differences in multiple aspects of HF, including epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, treatment, and prognosis, highlighting the need for sex-specific treatment guidelines.

INTRODUCTION

There were 64 million reported cases of heart failure (HF) globally in 2021, with women accounting for almost half of this total [1,2]. This incidence of HF is expected to continue to increase due to aging of the population and improved survival following acute cardiac events. Based on the National Health Information Database (NHID), the estimated prevalence rates of HF in Korea in 2020 were 2.55% for men and 2.62% for women, and the incidence is increasing rapidly as Korea is becoming a super-aged society [3]. Despite rapid progress in the management of HF, the current guidelines do not provide sex-specific recommendations [4,5]. In large clinical trials involving the drugs that make up the four pillars of HF therapy, the majority of cases have an ischemic etiology and more than 70% of participants are male, both of which have remained unchanged over time [6]. However, HF shows significant differences in prevalence, etiology, and phenotype between men and women, and responses to drugs also differ between the sexes. As the guidelines have been developed with bias toward baseline characteristics of men, Caucasians, and cases with ischemic etiology, they may not be suitable for the treatment of female patients with HF.

PREVALENCE AND INCIDENCE

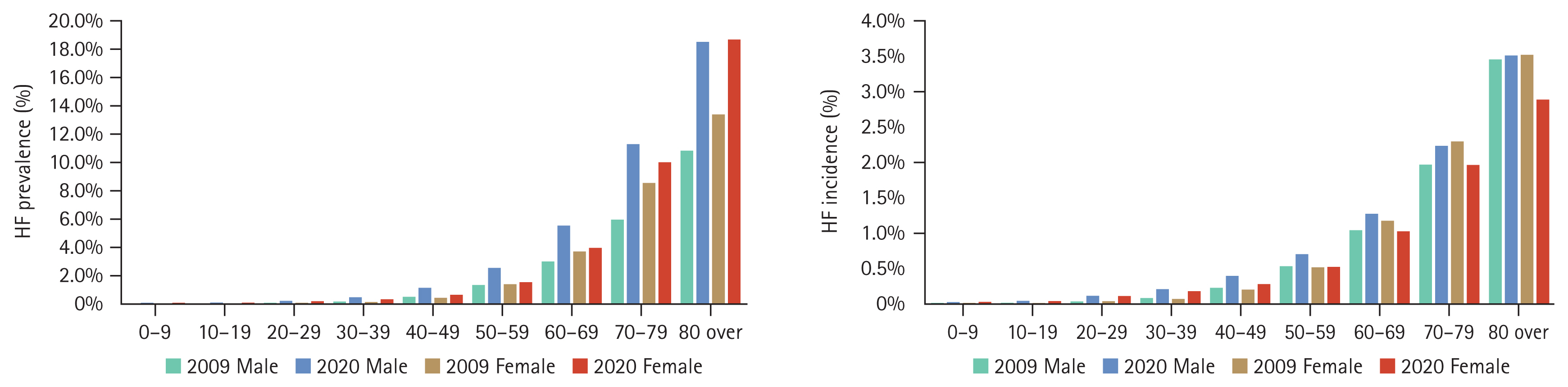

The prevalence and incidence of HF differ significantly between men and women [7]. The lifetime risk of developing HF is similar between men and women, with both sexes having approximately a 20% risk by age 40. However, by age 55, this risk increases to 33% in men and 29% in women [8]. After the age of 70, the prevalence of HF is higher in women than in men [9]. This variation can be attributed to differences in the prevalence of risk factors, such as hypertension and ischemic heart disease, between the sexes [8].

According to the NHID of South Korea, the prevalence of HF was higher in women after the age of 70 before 2010, while it increased sharply in men and surpassed that of women in the late 2010s [10] (Fig. 1). These changes could be partly caused by the characteristics of NHID, which uses International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes that depend on physicians’ recognition and patients’ use of medical facilities. coronary artery disease is a major cause of HF in men, and such disease, particularly myocardial infarction, is still underrecognized and underdiagnosed in women [11].

Comparison of the prevalence and incidence of heart failure (HF) between 2009 and 2020 by age and sex in South Korea.

Studies on HF tend to focus on worsening heart failure (WHF) episodes, which are associated with increased risks of hospitalization and death and are a major burden on the healthcare system because of their frequency, urgency, and prognostic impact. A recent study investigated sex-based differences in epidemiology, characteristics, and outcomes in a population of 102,116 patients with WHF in Northern California between 2010 and 2019. Overall, that study included a diverse real-life cohort with women accounting for 47.5% of patients. There were similar numbers of episodes of WHF in both sexes. There were differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between women and men, but the rates of hospitalization for HF and ED visits within 30 days of WHF episodes were similar. The rates of healthcare utilization and mortality were lower in women at 30 days [12]. A machine learning model with various clinical parameters showed that sex was not significantly related to HF rehospitalization after acute HF [12].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying HF also show sex-specific differences [8]. Women more frequently present with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), most commonly of ischemic origin, whereas men are more likely to develop HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [13]. This difference is partly due to variation in cardiac structure and function between the sexes, with women having smaller left ventricular (LV) volume and higher relative wall thickness for concentric remodeling and lower myocyte apoptotic index [13]. In addition, sex hormone status according to age and dominant comorbidities is also thought to affect the phenotypic differences [8]. There are clear sex differences in the prevalence and type of valvular heart disease, one of the most common causes of HF. Rheumatic valvular diseases and degenerative mitral valve diseases are more frequent in females across all age groups. Calcified aortic diseases are more common in males. Particularly, male sex has classically been considered a major risk factor for aortic stenosis due to the higher prevalence of bicuspid aortic valve in men [14].

Adult women tend to have increased innate immune response, which may cause more inflammation under conditions such as obesity, hypertension, preeclampsia, iron deficiency anemia, and diabetes mellitus. Inflammation-related reduced activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in the coronary artery can lead to ischemia or myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries, both of which occur at higher rates in women. Moreover, endothelial dysfunction is a key mechanism accounting for the development of HFpEF [8].

There are also specific forms of HF that exclusively affect women, such as peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM), defined as de novo pregnancy-associated cardiomyopathy with LV systolic dysfunction (typically with left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] < 45%) presenting toward the end of pregnancy or in the months following delivery in the absence of other causes [15]. Premature menopause either by iatrogenic or natural causes can cause LV diastolic dysfunction with prone to development of HF [16]. Breast cancer is also female-sex specific, and its treatments, such as anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens and trastuzumab, may result in cardiomyopathy [17]. In the meanwhile, radiotherapy which consist principal therapeutic method of breast cancer, is associated with increased risk of ischemic heart disease, such as myocardial infarction [16]. Stress-induced cardiomyopathy is known to affect more women than men, and the etiologic differences are also consistent in reports: emotional stress in women, and physical stress in men [7,8].

NATRIURETIC PEPTIDE DIFFERENCES

Natriuretic peptides (NPs) are released by the myocardium in response to stretching and promote natriuresis, vasodilation, and myocardial relaxation. Among the various NPs, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) have come to play very important roles in the diagnosis of HF. If possible, measurement of NPs is recommended. The guidelines suggest plasma concentrations of BNP < 35 pg/mL, NT-proBNP concentration < 125 pg/mL, or midregional proatrial natriuretic peptide (MR-proANP) concentration < 40 pmol/L for exclusion of HF diagnosis [4]. However, concentrations of each of these NPs tend to be higher in healthy women than in healthy men of similar age partially due to the suppressive effect of testosterone [18]. In addition, large observational studies have shown an inverse relation between NT-proBNP level and obesity that is more pronounced in females than males. The recent Generation Scotland Scottish Family Health Study (GS:SFHS) also showed that NT-proBNP ≥ 125 pg/mL is common in females without classical cardiovascular risk factors [19]. The lowest 97.5th percentile value of NT-proBNP was 209 pg/mL for women over 30 years old vs. 102 pg/mL for men, and the authors suggested the use of age and sex-specific thresholds. Considering the available evidence, it is reasonable to raise the threshold for women.

SEX-RELATED GENETIC DIFFERENCES IN HF

Some X-linked diseases, such as Becker muscular dystrophy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), show higher incidences in males [8], and cardiomyopathies related to mitochondria are usually maternally transmitted.

However, most mutations that cause cardiomyopathy occur on the autosomes. This is because most of the proteins that make up the myocardium, such as actin, myosin, and titin that compose the sarcomere, are encoded by autosomal genes. Titin-truncating variants (TTNtv) show higher penetrance and younger age at presentation in men, who have higher rates of atrial fibrillation and poorer cardiac function than women with these variants [20]. Women with TTNtv are more likely to develop PPCM, suggesting a role for sex hormones in influencing gene expression [21]. Female DCM with Lamin A/C (LMNA) variants have a 45% lower risk of life-threatening arrhythmias than men [20]. Males carrying LMNA mutations present clinical manifestations at a younger age than females [22]. In one multicenter study, there was a trend toward a lower risk of major cardiovascular events in women who had filamin C (FLNC) genetic variants (p = 0.066) [23]. Males with pathogenic variants in RBM20 were significantly younger, had a lower ejection fraction at diagnosis and had higher rate of heart transplantation (HTx) than females [24].

Sex-related differences in etiology of HF are summarized in Figure 2.

THERAPEUTIC DIFFERENCES

Sex differences in body composition and drug metabolism

There are a number of fundamental physiological differences between females and males. In terms of body composition, women generally have a higher body fat percentage than men [25]. This affects the volume of distribution (Vd) of lipophilic drugs, defined as the total amount of drug in the body/blood plasma concentration of drug. Lipophilic drugs tend to have a greater Vd in women, potentially leading to prolonged action and altered pharmacokinetics (PKs). Moreover, men typically have a higher lean body mass compared to women. Lean body mass is a crucial determinant of the Vd of hydrophilic drugs. Drugs that are hydrophilic will have a higher Vd in men, affecting the drug concentrations in the plasma and tissue. In addition, men have a higher total body water percentage than women, which can influence the PK of hydrophilic drugs as they tend to have a larger Vd in individuals with higher body water content [25].

Differences in drug metabolism also lead to differences in PKs and pharmacodynamics (PDs). There are sex-specific differences in the activities of liver enzymes responsible for drug metabolism. For example, cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes exhibit sex-dependent variation. Women generally have lower activity of CYP1A2 and higher activity of CYP3A4 compared to men, impacting the metabolism of drugs processed by these enzymes [26]. Differences in renal clearance and gastrointestinal enzyme activity also influence drug absorption and excretion. Finally, hormonal fluctuations, particularly in women, can significantly impact drug metabolism. Estrogen and progesterone levels, which vary with the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause, can alter enzyme activity and drug metabolism pathways [27].

Understanding these sex-specific differences is very important for the effective treatment of HF. For example, dosing regimens for drugs such as beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and diuretics may require adjustment based on the sex of the patient to optimize therapeutic outcomes and minimize adverse effects. Precision medicine approaches taking these physiological differences into consideration will lead to more personalized and effective management of HF.

Pharmacological therapy

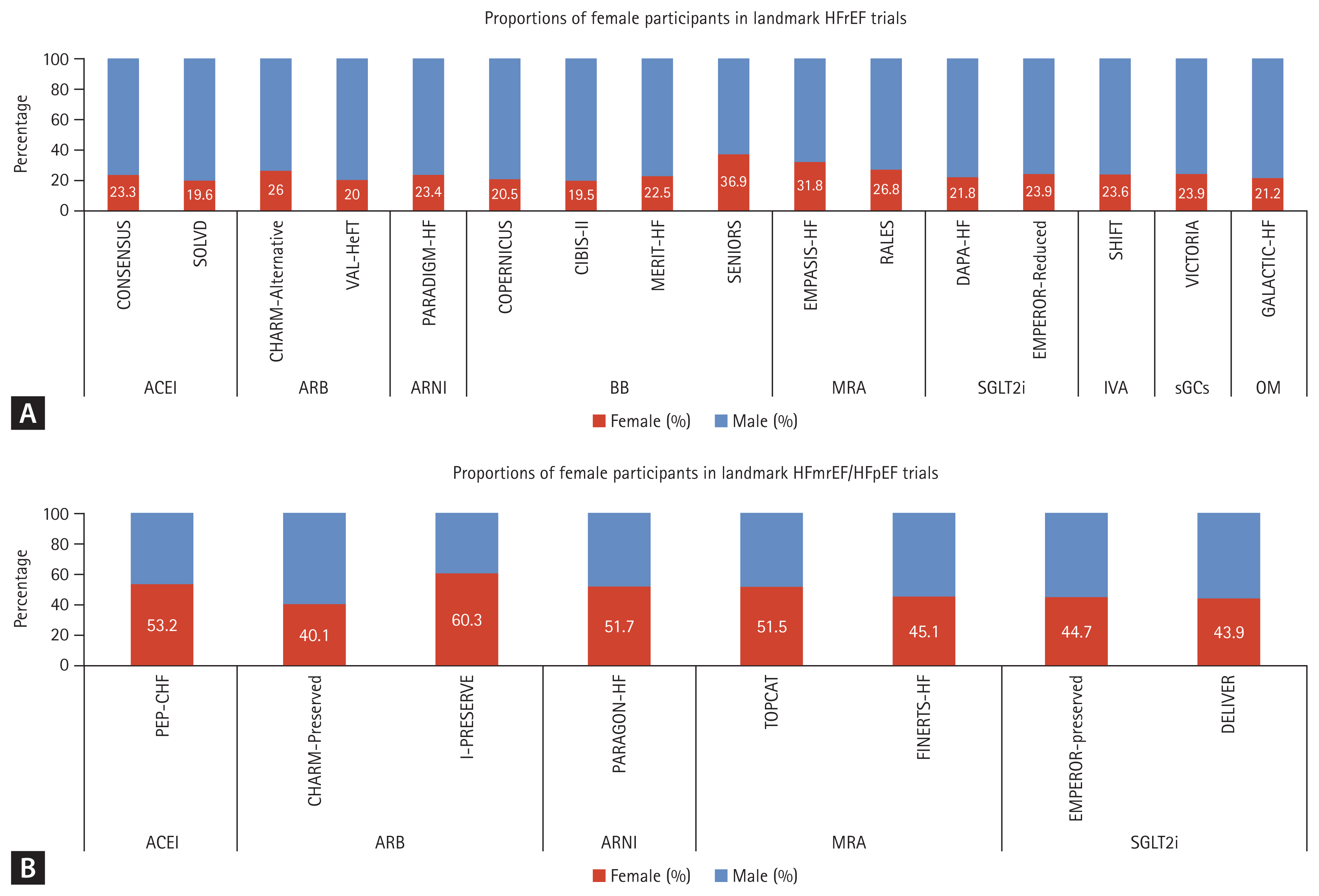

The “four pillar-therapy” is well established in HFrEF, and titrating these therapies within 4 weeks is related to better prognosis [4,28]. However, an examination of the baseline characteristics of landmark HFrEF studies starting from the 1990s revealed notable sex-related disparities (Fig. 3). The proportion of male participants was 70–80%, with female participants accounting for only 20–30% of patients, with a significant portion having an ischemic etiology. Although subgroup analyses in all studies have shown significant therapeutic effects in women, allowing guidelines to be applied regardless of sex, it is essential to take these sex disparities into consideration when treating individual patients. Accounting for the PK and PD of each medication based on sex is crucial to maximize patient safety and treatment efficacy. Therefore, it is important to take the sex-specific effects of each medication and their PK/PD characteristics into consideration in individual cases.

Proportions of female participants in landmark (A) HFrEF and (B) HFmrEF/HFpEF trials. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; BB, beta-blockers; HFmrEF, heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; IVA, ivabradine; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; OM, omecamtiv mecarbil; sGCs, soluble guanylyl cyclase stilmulator; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angio-tensin II receptor blockers

Captopril is better absorbed in female patients when administered on an empty stomach. In addition, adverse drug reactions, including cough, taste disturbance, skin rash, increased serum levels of creatinine, and gastrointestinal upset, are more frequently observed in females than in males [29].

The original analyses of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) in HF studies that began in the 1980s did not include sex differences. Subsequent subgroup analyses showed statistically significant differences in overall mortality and hospitalization for HF in men but not in women [30]. In a meta-analysis, the pooled random effects estimates for mortality from the six studies (CONSENSUS, SAVE, SMILE, SOLVED-Prevention, SOLVD-Treatment, and TRACE) with RR data yielded values of 0.82 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.74–0.90) for men and 0.92 (95% CI 0.81–1.04) for women [31]. That study did not find evidence that women with asymptomatic LV dysfunction may not have reduced mortality when treated with ACEI [31].

There were no SRDs in the PKs of candesartan, irbesartan, or valsartan after normalization of the dose for body weight. Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) have better efficacy and adherence profiles than ACEIs in women with HFrEF but not in men [32]. Female patients may have lower risks of death and hospitalization for HF at half the guideline-recommended doses compared to males [33].

Sacubitril-valsartan (angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor)

There were no SRDs in the PK of angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) [34]. The PARADIGM-HF trial showed superiority of ARNI compared to enalapril in reducing the primary end points, mortality, and hospitalization for HF [35]. In subgroup analyses, similar prognostic benefit was found for the primary end point in both men and women. However, with regard to cardiovascular death, ARNI showed a significant benefit in men but not in women.

The large-scale HFpEF trial PARAGON-HF showed significant benefits of ARNIs in women on subgroup analysis (women 0.73 [95% CI 0.59–0.90] vs. men 1.03 [0.84–1.25 p = 0.017], although it failed to meet the primary end point of composite first and recurrent hospitalization for HF and death from cardiovascular causes in the total population. Women comprised 52% of the study population in PARAGON-HF, and were older, had higher rates of obesity, reduced frequency of coronary artery disease, higher baseline LVEF, worse symptoms of HF, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and lower NT-proBNP levels compared to men. Overall, women had higher rates of hospitalization for HF and lower rates of cardiovascular death compared to men [36]. The authors suggested that women may have a more favorable response to neprilysin inhibition than men because the normal LVEF range is higher in women than in men, reflecting sex-related differences in cardiac remodeling in response to factors including blood pressure and age, and there are also known sex differences in NP biology where any reduction in cGMP-protein kinase G signaling attributable to a relative NP deficiency may be exacerbated in post-menopausal women by loss of alternative estrogen-dependent stimulation of this pathway through eNOS activation and nitric oxide generation. Consequently, by augmenting NPs, sacubitril-valsartan may be of greater benefit in women than in men, if women have deficient cGMP–protein kinase G signaling [36].

In terms of adverse events, the differences between sacubitril-valsartan and valsartan were similar in women and men. There were too few cases of angioedema for meaningful subgroup analysis according to sex [36].

Beta blockers

Beta blockers (BBs) are among the oldest drugs included in the four pillars of HF therapy following ACEIs/ARBs and their effects have been examined in many clinical studies. However, the proportions of women included in these clinical studies were about 20–30% (Fig. 3A).

At present, there are no sex-specific dosage guidelines for administration of BBs. However, among the drugs included in the four pillars, caution is required for BBs because systemic exposure is greater in women than in men at the same dosage. Women were reported to show higher plasma levels of metoprolol and propranolol due to slower Cl and lower Vd (hydrophilic drugs), resulting in a greater reduction in exercise heart rate and systolic blood pressure than in men [37]. Moreover, hormones such as estrogens and progesterone can inhibit the cardiac expression of β1-adrenoceptors, thereby reducing β-adrenergic-mediated stimulation [37]. In addition, women typically have greater nerve activity, higher cardiac noradrenaline spillover, and increased β2-adrenoreceptor sensitivity [38].

The clinical impact of the PK/PD differences in BB depending on sex was examined in the BIOSTAT-CHF study. The lowest rates of death or hospitalization for HFrEF were observed at 100% of the target BB dose in male patients, while female participants showed approximately 30% lower risk at only 50% of the target dose [33]. However, analyses of pooled data from the CIBIS-II, MERIT-HF, and COPERNICUS trials showed that the overall mortality benefit was similar regardless of sex [39].

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists

The two well-established drugs spironolactone and eplerenone and the new drug finerenone are all mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) that block the final stage of the rennin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS). No sex-related differences in the PKs of MRAs have been reported [40]. The Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study (RALES) and the Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF) trial showed marked reductions in the primary end point [41,42]. However, treatment with spironolactone did not show a reduction in the incidence of the time-to-first composite of cardiovascular death, aborted cardiac arrest, or hospitalization for HF in patients with LVEF ≥ 45% in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. There were no sex-related differences in clinical outcomes in these trials.

Finerenone is a nonsteroidal MRA used for the treatment of HF, which is characterized by its high selectivity for mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) and reduced risk of hyperkalemia [43]. In 2021, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted approval for the use of finerenone for the treatment of adult patients with chronic kidney disease (stages 3 and 4) associated with type 2 diabetes, based on the results of large phase III clinical trials, such as FIDE-LIO-DKD, FIGARO-DKD, and FIDELITY [44,45]. In a post hoc analysis of cardiovascular and kidney outcomes by age and sex, finerenone was shown to improve cardiovascular and kidney composite outcomes with no significant differences between subgroups according to sex, although the rate of hospitalization for HF was higher in males [46]. The results of the FINEARTS-HF trial were announced at the European Cardiology Society Congress 2024 and published concurrently in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) [47]. Patients with symptomatic HF and LVEF ≥ 40% were randomized in a 1:1 manner to receive finerenone at a maximum dose of 40 mg daily (20 mg if eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, n = 3,003) or placebo (n = 2,998, female 45%). The primary outcome, a composite of worsening HF events (first or recurrent unplanned hospitalization for HF or urgent visit) and cardiovascular death, for finerenone vs. placebo was 14.9 vs. 17.7 events per 100 patient-years, respectively. Subgroup analysis showed a significant decrease in the primary end point in females vs. males. However, the authors commented that the confidence intervals in subgroup analysis were not adjusted for multiplicity [47]. Therefore, further studies of the sex differences in the effects of the new MRA finerenone are warranted.

Sodium glucose transporter inhibitors

Sodium glucose transporter inhibitors (SGLT2i) have been included in the current HF guidelines because they show marked hospitalization for HF and cardiovascular mortality risk reduction despite being used in addition to the previously mentioned essential HF medications.

These medications are effective across all categories of HF, regardless of LVEF, and exhibit clinical advantages in both men and women [48–51]. However, a recent meta-analysis of pooled data from four major randomized controlled trials on SGTIs suggested higher rates of primary composite outcomes in women compared to men [52]. There is evidence of sex differences in terms of side effects. The incidences of mycotic infections of the urinary and genital tract were higher in women, while acute renal failure and limb ischemia were more frequent in male patients receiving SGTIs [40].

Soluble guanylyl cyclase stimulator (vericiguat)

The soluble guanylyl cyclase stimulator (sGC) vericiguat is included in “quintuple therapy” and is expected to play a role in the treatment of WHF. The sex of patients was not a significant covariate in population PK analysis of patients with HFrEF. Rather, lower body weight seemed to be associated with an increase in drug exposure [53]. The only large-scale randomized controlled trial performed to date, VICTORIA, showed no significant sex-related differences in the efficacy or safety profile of vericiguat in patients with LVEF < 45% [54]. Recently reported real-world data from Germany showed that women started on vericiguat were older than men (76 ± 13 yr vs. 72 ± 12 yr, respectively). There were no sex- or age-specific differences in the starting dose of vericiguat or uptitration time. However, women reached the maximum dose of 10 mg less often compared to men (34% vs. 37%, respectively). The discontinuation rate tended to be higher in women than in men, but the confidence intervals overlapped and the difference diminished toward the end of the observation period. Nevertheless, the median time until discontinuation was shorter in women than in men (29 days vs. 42 days, respectively) [55]. These results suggest that women had poor adherence to the drug due to side effects or other reasons.

The sex-related differences in principal HF drugs are summarized in Table 1.

Digoxin

Digoxin is no longer a principal drug used to treat HF and the continuously decreasing prescription rate reached 10% in the mid-2010s [56]. Sex-specific analysis was not performed in the pivotal trials of digoxin (DIG, PROVED, RADIANCE) in patients with HFrEF. Therefore, data on sex-related differences in the use and effects of digoxin are mainly based on post hoc analyses. The trials of digoxin were underpowered to test for the interaction of sex, and there has been debate on selection bias, such as the higher rate of prescription in older adult women with more comorbidities [57]. A retrospective analysis of the DIG trial including 4,944 women demonstrated significant linear relations between serum drug concentration and all-cause mortality in women and men [58]. At low serum concentrations of drug (0.5–0.9 ng/mL) a reduction in all-cause mortality was observed in men but not in women compared to placebo. The combined end point of all-cause mortality or first hospital stay due to worsening HF, or first hospital stay due to worsening HF alone, and hospital stay for worsening HF was significantly reduced in both sexes. Therefore, the currently recommended serum concentration of digoxin is 0.5–0.9 ng/mL in general [59]. However, caution is needed considering the reduced Vd and lower clearance in women, so slightly lower plasma levels are recommended in women than in men (< 0.8 ng/mL) [60].

Sex differences in device therapy: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator & cardiac resynchronization therapy

An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is recommended as primary prevention in patients with LVEF < 35% despite guideline-directed medical therapy and secondary prevention in various situations [4]. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation rates for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death are lower in women.

On the other hand, cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is recommended for symptomatic patients with HF in sinus rhythm with QRS duration ≥ 150 ms and left bundle branch block (LBBB) QRS morphology and LVEF ≤ 35% despite optimal medical therapy to improve symptoms and reduce morbidity and mortality rates. Female patients generally have LBBB with nonischemic etiology and dyssynchrony at higher rates and have better responses to CRT than male patients. Smaller body size and cardiac dimensions have been suggested as possible reasons for the sex-related disparities in response to CRT [61].

Etiology of cardiogenic shock and differences in management

The most common forms of cardiogenic shock (CS) are acute myocardial infarction (AMI)-CS and HF-CS [62]. A recent report presented the results of a Cardiogenic Shock Working Group (CSWG) analysis of 5,083 patients with AMI-CS and HF-CS (30% women, n = 1,522; 70% men, n = 3,560) [63]. More women presented with de novo HF-CS compared to men (26.2% vs. 19.3%, respectively; p < 0.001). Women with HF-CS had decreased survival at discharge (69.9% vs. 74.4%; p = 0.009) and greater severity of CS compared to men. Women with HF-CS were less likely to receive HT or OHT (6.5% vs. 10.3%; p < 0.001) or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation (7.8% vs. 10%; p = 0.01). Regardless of CS etiology, women had higher rates of vascular complications (8.8% vs. 5.7%; p < 0.001), bleeding (7.1% vs. 5.2%; p = 0.01), and limb ischemia (6.8% vs. 4.5%; p = 0.001) than men [63]. These results were similar to previous studies indicating that women are more likely to die, are less likely to be referred to tertiary care shock centers, have lower rates of early revascularization, and have higher adjusted in-hospital mortality rates compared to men in AMI-CS [64–66]. Anatomical differences, such as small vessel sizes, could influence the incidence of limb ischemia, as women have smaller iliofemoral arteries than men, even when matched for body mass index and peripheral artery disease. Therefore, securing vascular access should always be kept in mind in preparation for emergency temporary mechanical circulatory support (MCS) when managing female patients with CS.

Socioeconomic factors are thought to result in differences in the rates of MCS, HTx, and LVAD implantation. Analysis of AMI-CS and ADHF data using National Inpatient Sample (NIS) showed that women were more likely to be older, non-Caucasian, insured by Medicare, and to have a higher burden of comorbidities, including hypertension and cerebrovascular disease, than men [67]. Women were less likely to receive a peripheral ventricular assist device or pulmonary arterial catheter. Consistent with previous studies, women requiring peripheral MCS had a higher in-hospital mortality rate than men.

There are still no Korean data on sex differences in incidence and management of CS, and further research is warranted.

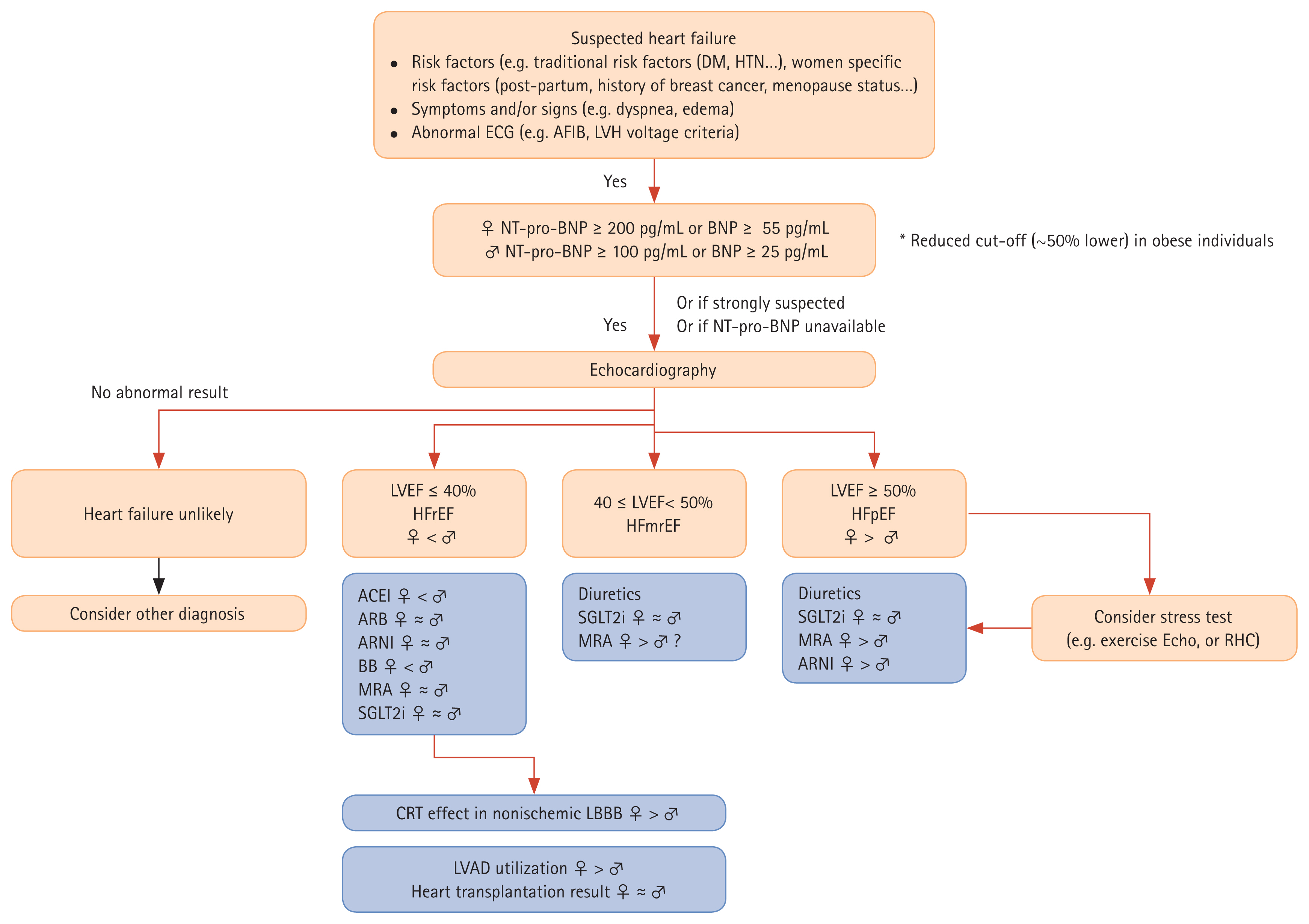

CONCLUSIONS AND PROPOSALS FOR MANAGEMENT PROTOCOLS

This review presented an outline of the sex-related differences in etiology, diagnostic approach, treatment response, and prognosis of HF. Future perspectives for sex-specific diagnostic and therapeutic strategies are proposed in Figure 4. Such attempts to distinguish diagnosis and treatment according to sex will lead to improved individualized management of HF.

Proposed diagnostic and management algorithms for heart failure in women and men. Diagnostic flows are presented in orange boxes and management/treatment flows are shown in blue boxes. ♀ < ♂, more prevalent in women or more documented clinical beneficial effects in women; ♀ ≈ ♂, similar clinical effects in both sexes; ♀ < ♂, more prevalent in men or more documented clinical beneficial effects in men. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AFIB, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; BB, beta-blockers; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG, electrocardiogram; Echo, echocardiography; HFmrEF, heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HTN, hypertension; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NTproBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; RHC, right heart catheterization; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor.

Notes

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Chan Joo Lee for sharing the data used in Figure 1.

CRedit authorship contributions

Soo Yong Lee: conceptualization, investigation, writing - original draft; Seong-Mi Park: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing - review & editing, visualization, supervision

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

None