Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis and local ablative therapy of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

Article information

Abstract

Advancements in diagnostic technology have led to the improved detection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) and thus to an increase in the number of reported cases. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) technology, including in combination with contrast-enhanced harmonic imaging, aids in distinguishing PNETs from other tumors, while EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration or biopsy has improved the histological diagnosis and grading of tumors. The recent introduction of EUS-guided ablation using ethanol injection or radiofrequency ablation has offered an alternative to surgery in the management of PNETs. Comparisons with surgery have shown similar outcomes but fewer adverse effects. Although standardized protocols and prospective studies with long-term follow-up are still needed, EUS-based methods are promising approaches that can contribute to a better quality of life for PNET patients.

INTRODUCTION

The pancreas performs both exocrine and endocrine functions. The latter are managed through hormones produced in the islets of Langerhans, including insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, ghrelin, and pancreatic polypeptides. Tumors that originate from these islet cells are referred to as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs). Although the majority of PNETs are nonfunctioning, patients with functioning PNETs (F-PNETs) typically have a better prognosis, likely because they are symptomatic, enabling earlier detection [1–4].

PNETs are relatively uncommon, constituting 2–3% of all pancreatic tumors [5,6]. Increases in the number of cases are largely due to the expanded use of high-quality imaging techniques. The incidence of low- and intermediate-grade PNETs with a relatively indolent clinical course has significantly increased [6,7]. Cross-sectional imaging with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging are used to evaluate patients with PNETs, but endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is of superior sensitivity in the detection of these tumors [8–10]. When performed by skilled practitioners, EUS offers high resolution that enables the detection of focal lesions as small as 2–5 mm [11]. The accurate detection of small PNETs has significant prognostic implications, as it facilitates both diagnostics and treatment planning: the ability to obtain tissue samples with EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA)/fine-needle biopsy (FNB) is crucial for both [12,13]. The development of minimally invasive EUS-guided local ablation therapies is a significant advancement in the treatment of PNETs [14–17], especially for patients who may not be candidates for surgery [18,19]. Table 1 summarizes the endoscopic diagnostic and treatment strategies available for the comprehensive evaluation and management of PNETs, based on the guidelines for the endoscopic management of PNETs provided by the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS) and the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) [1,4,20].

A guide to the endoscopic management of PNETs and a summary of the recommendations of the NANETS and ENETS

This review explores the role of EUS in the diagnosis of PNETs and extends the discussion to include interventional procedures such as EUS-guided ablation therapy. It thus provides a comprehensive assessment of both the diagnostic and therapeutic applications of EUS in the management of PNETs.

ROLE OF EUS IN DIAGNOSIS OF PNETs

Features of EUS findings

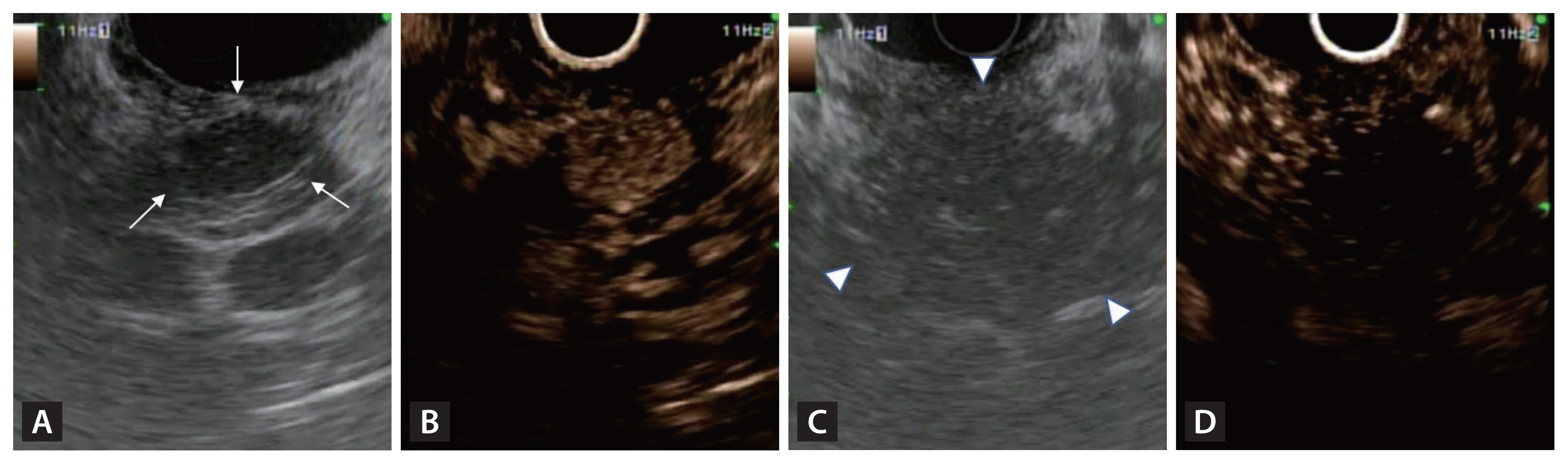

Conventional cross-sectional imaging modalities such as CT have a reported sensitivity of 70–80% for detecting PNETs [11]. However, the rate is significantly lower for smaller lesions, particularly those < 5 mm in size [11,21]. EUS has a higher detection rate for small PNETs (< 10 mm) [11] and is helpful for differentiating focal pancreatic neoplasms [22]. Typically, a PNET is well-demarcated, homogeneous, and hypoechoic, in contrast to pancreatic cancer, which in most cases is ill-defined, heterogeneous, and hypoechoic (Fig. 1A, C) [23]. EUS should be performed to identify multifocal tumors in MEN1 patients. It is also beneficial for measuring the distance between the main pancreatic duct and the PNET, which is crucial for planning EUS-guided ablation therapies.

B-mode endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS (CH-EUS) images of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PNET). (A) A typical PNET with well-demarcated, homogeneous, hypoechoic lesion on B-mode EUS (white arrows). (B) Hyper-enhancement of PNET on CH-EUS. (C) A pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with ill-defined, heterogeneous, hypoechoic lesions on B-mode EUS (white arrowheads). (D) A pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with hypo-enhancement on CH-EUS.

Role of contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS

Contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS (CH-EUS) is a valuable tool for evaluating pancreatic tumors because it allows real-time observations of the hemodynamics within the tumor mass. During this process, the microbubbles within contrast agents are disrupted by ultrasound waves, generating signals that can be detected by ultrasound. PNETs are typically rich in blood vessels, so they exhibit hyperenhancement during the early phase, and this persists into the delayed phase. CH-EUS yields high diagnostic accuracy, with a sensitivity of 96–100% and a specificity of 76–82% for identifying PNETs [24]. Similar to ultrasound, CH-EUS can distinguish between PNETs and pancreatic cancer, as PNETs exhibit hyperenhancement (Fig. 1B) whereas pancreatic cancer is characterized by hypoenhancement (Fig. 1D). CH-EUS combined with time-intensity curve analysis offers valuable insights that are useful in the diagnosis and grading of PNETs [25]. The aggressiveness of PNETs on CH-EUS can be assessed based on heterogeneous enhancement during the early arterial phase [26]. CH-EUS increases the precision of EUS-FNA by identifying hypervascular sites within lesions, so clinicians can avoid sampling areas with dense fibrosis, thus improving the diagnostic yield [27]. CH-EUS can also be used in follow-up examinations to evaluate the treatment response after EUS-guided local ablation therapy [28].

Histological diagnosis and tumor grading

As noted above, EUS is an essential tool in the histological diagnosis and tumor grading of PNETs. The sensitivity of EUS-FNA/FNB for diagnosing PNETs ranges from 85–93%, with a specificity of up to 100% [9,29,30]. Samples obtained by EUS-FNA/FNB can be used for immunohistochemical staining of hormones or next-generation sequencing (NGS). Mutation detection by NGS provides important information, because certain somatic mutations, including MEN1, DAXX, ATRX, and mTOR, present in varying frequencies in sporadic PNETs but are associated with a high risk of aggressiveness and tumor metastasis [31,32,33].

The grading of PNETs influences the treatment approach. The fifth edition of the 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) classification categorizes neuroendocrine neoplasms into NET and neuroendocrine carcinomas according to their molecular variance [34]. Tumor classification is based on the grade (differentiation), mitotic rate, and Ki-67 index; several studies have found that NETs with higher mitotic rates and elevated Ki-67 indices tend to have more aggressive clinical behavior, resulting in a poorer prognosis [35,36]. The present approach to managing PNETs relies heavily on the stage and grade of the disease.

Nonetheless, tumor grading via EUS-FNA/FNB may lead to underestimation, because only a portion of the tumor is sampled. A recent meta-analysis assessed discrepancies in tumor grade between surgical specimens and preoperative biopsy, and found that approximately 15% of tumors were undergraded (median Ki-67 difference of 3%) when assessed based on biopsy compared with after surgical resection [37]. EUS-FNB is more likely than EUS-FNA to yield adequate samples for Ki-67-based grading and the results are in closer alignment with those of surgical histology, thereby reducing the risk of preoperative undergrading of PNETs [12]. The same meta-analysis revealed a high concordance in grading between preoperative EUS samples and surgical specimens when sampling was performed with EUS-FNB than with EUS-FNA (84.2% vs. 79.5%) [37]. Therefore, NANETS recommends EUS-FNB over EUS-FNA when feasible, as well as the use of EUS in planning management strategies for PNETs [1].

EUS-GUIDED LOCAL ABLATIVE THERAPIES OF PNETs

Although surgery is currently the standard care for PNETs, pancreatic resection carries a substantial risk of morbidity (20–40%) and mortality (2%) [38]. Tumor size is known to correlate with an increased risk of developing metastatic disease, and guidelines recommend that tumors ≥ 2 cm should be resected. However, there is no clear evidence of a survival benefit in patients who undergo resection for NF-PNETs < 2 cm; rather, the decision should be based upon patient age, site of the tumor, co-morbidities, and tumor growth rate, and the benefits of curative resection must be weighed against postoperative morbidity and mortality.

NF-PNETs < 2 cm can be monitored using radiologic surveillance, but small tumor size alone does not guarantee that the lesion is benign, as the malignant potential of these tumors is not negligible. Additionally, with the widespread adoption of cross-sectional imaging, PNETs are more commonly found in younger individuals, but life-long tumor surveillance is troublesome for both psychological and economic reasons. A minimally invasive treatment approach using EUS may address the as-yet unmet needs of patients with PNETs.

Patient selection

Although no consensus protocol has been reached, the proposed indications for EUS-guided local ablation therapies, such as EUS-guided radiofrequency ablation (EUS-RFA) and EUS-guided ethanol ablation (EUS-EA), include patients with small (≤ 2 cm) localized insulinomas or grade 1 NF-PNETs who are not eligible for or refuse surgery [19,28,39–43]. These recommendations are based on recent clinical trials and guidelines, such as the ENETS 2023 guidelines [4,20], that highlight the potential role of these minimally invasive techniques in specific cases. For F-PNETs, a distinct approach is required because of the symptoms induced by the tumors, such as endogenous hyperinsulinemia leading to hypoglycemia; in these patients, minimally invasive endoscopic procedures can provide immediate relief from symptoms.

EUS-EA

Ethanol ablation induces coagulation necrosis of tumor cells due to cellular dehydration, protein denaturation, and vascular occlusion [44]. Early research on the porcine pancreas suggested that EA is safe, but concerns emerged regarding the use of 98% instead of 50% ethanol, as higher concentrations can cause more severe pancreatic parenchymal damage and increase the possibility of acute pancreatitis [45]. The first report of EUS-EA use in a human was published in 2006: it described the treatment of a 13-mm symptomatic insulinoma in a patient who was not a candidate for surgery. The administration of 8 mL of 95% ethanol led to complete resolution of the hypersecretion syndrome [16].

Technique

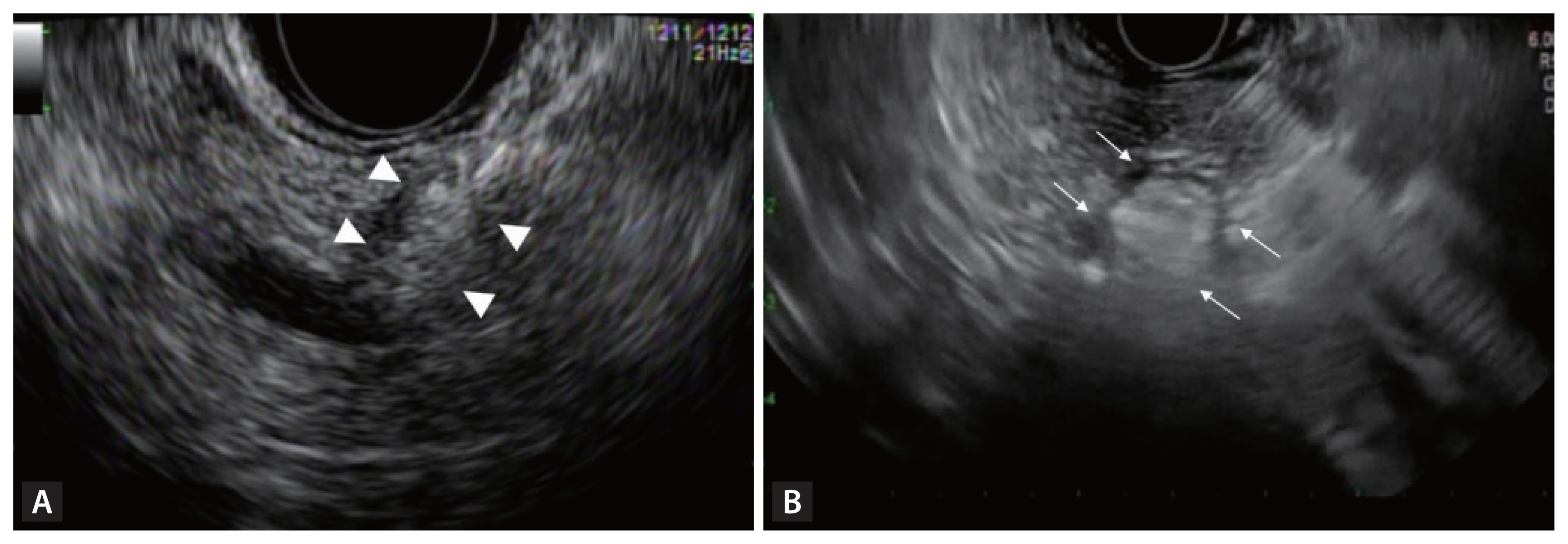

No protocol has been established for EA, but 50–99% ethanol is most commonly used, either alone or mixed with lipiodol at a 1:1 ratio. Generally, when a patient meets the indications, the tumor is treated in 1–4 sessions, with 0.8–3.1 mL of ethanol injected each time [43,46–51]. A 22- or 25-gauge FNA needle is used to inject the ethanol into the tumor under real-time EUS visualization, until the hyperechoic blush extends to the tumor margin (Fig. 2A). This procedure is followed by post-treatment fluoroscopy when an ethanol-lipiodol mixture is injected [49]. Additional ablation sessions may be performed if viable lesions are detected on follow-up imaging.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided ablation. (A) Hyperechoic blush within a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor following ethanol injection (white arrowheads). (B) Echogenic bubbles appearing around the needle after activation of radiofrequency ablation probe (white arrows).

One small prospective pilot study explored the effectiveness of early re-treatment with ethanol after the initial treatment [50]. The five patients had received ethanol injections and were monitored using contrast-enhanced CT for 3 days after treatment to detect any residual enhanced tumor areas, indicating incomplete ablation. Three of the five patients needed a second treatment soon after the initial procedure, resulting in an overall complete ablation rate of 80%.

Efficacy and safety

Table 2 summarizes the results of previous studies on EUS-EA in the treatment of PNETs [43,46–51]. The pooled clinical success rates were 78.8% and 63.5% for F-PNETs and NF-PNETs, respectively. The pooled adverse event (AE) rate was 7.8% across both types of PNETs. In the prospective cohort study of NF-PNETs treated with EUS-EA, the median volume of ethanol-lipiodol mixture injected per session was 1.1 mL in 32 patients [49]. Complete ablation was achieved in 60% of tumors, with a 3.2% procedure-related AE rate during a median 42-month follow-up period [49]. Yan et al. [51] conducted a single-center investigation of nine patients with insulinoma, in whom ethanol ablation of the tumor was performed for a total of 14 times. The overall response rate was 64.3% when calculated individually for each ablation. Long-term symptom relief was achieved in four of the patients, with an average duration of 3 years. The reported recurrence rate was 55.6% [51], significantly higher than the previously reported rate of 15% [52].

A retrospective propensity score-matching analysis comparing EUS-EA and surgery for small NF-PNETs revealed comparable 10-year overall survival and disease-specific survival rates [43]. Early major AEs developed more frequently after surgery (11.2%) than after EUS-EA (0%, p = 0.003). Late major AEs developed in 3.4% of the patients after EUS-EA and in 10.1% after surgery; the difference was not significant (p = 0.073). In the surgery group, one patient died of pulmonary embolism as a late major AE. These findings suggest that EUS-EA can be used as a first-line treatment for NF-PNETs [43].

The AEs of EUS-EA might be attributed to the amount of ethanol injected. Park et al. [46] treated all three of their patients with pancreatitis using > 2 mL of ethanol per session, noting that a high volume of ethanol injection increases the risk of complications. Methods for reducing the total ethanol volume continue to gain interest; more recently, Choi et al. [49] found that the AE rate was low (3.2%) following the injection of an ethanol-lipiodol mixture. To date, no guidelines for the type of injection needle have been established. One study reported that the use of a needle with multiple side holes resulted in peripancreatic ethanol leakage and pancreatitis [48]. Another recommended careful intratumoral injection using a single-hole needle when using EA to minimize procedure-related complications, noting that the needle should be left in place immediately beyond the proximal edge for approximately 1 min before removal to facilitate ethanol distribution within the tumor and prevent leakage [53]. The optimal needle size, volume, and ethanol concentration for injection require further investigation to optimize treatment effectiveness and minimize AEs.

EUS-RFA

In RFA, high-frequency alternating currents are used to deliver thermal energy and thereby trigger coagulation necrosis to reduce tumor bulk. The 200- to 1,200-kHz high-frequency alternating current generates heat near the electrode, targeting the tumor while sparing adjacent healthy tissue [54]. However, although the heating effect is confined to a small area around the RFA electrode, excessive application can lead to heat conduction over a broader region and thus to tissue charring. This can be avoided by cooling the active electrode. The vaporized water and charred tissue act as insulators, leading to increased impedance of the treated area. This change signals the need to immediately stop the delivery of radiofrequency energy [55]. Armellini et al. [56] were the first to report successful EUS-RFA; their older patient refused surgery for a 2-cm NF-PNET in the pancreatic tail and was treated in a single session using an 18G EUSRA needle-electrode.

Technique

The 19G RFA probe (EUSRA; STARmed Co., Ltd., Goyang, Korea) has a 10-mm-long needle-shaped electrode (total length 140 cm) and an internal cooling system in which the electrode is perfused with chilled saline delivered via a pump, to prevent tissue charring during the procedure [39]. A different RFA system employs a monopolar radiofrequency probe (Habib™ EUS-RFA catheter; Emcision Ltd., London, UK) with a diameter of 1 Fr (0.33 mm) and a working length of 190 cm [57]. This Habib probe can be inserted through a 19G or 22G FNA needle and connected to a RFA generator for regulated energy delivery; the generator automatically adjusts the power output to maintain an optimal ablation temperature. This probe is a monopolar device and requires the use of patient grounding or a diathermy pad.

RFA settings vary widely across studies [58]. Khoury et al. [59] conducted a meta-analysis and found that a power setting of < 50 W achieved clinical success in 92.4% of patients, and 50 W in 84.6%. Recent treatments typically utilize a 30 W power setting for 10–20 s [60]. However, further studies are needed to determine the optimal power settings for treating PNETs.

Under EUS guidance, the needle electrode is inserted into the target lesion while minimizing its traversal through normal pancreatic parenchyma and avoiding major vessels and ducts [41]. The tip of the echogenic needle is positioned at the distant end of the lesion. Energy delivery is initiated once the location of the needle tip within the margin of the lesion has been confirmed using EUS [19,41]. As shown in Fig. 2B, the appearance of echogenic bubbles around the needle following activation indicates effective ablation. Multiple passes may be necessary to ensure complete ablation of the entire lesion, depending on the device’s characteristics and the lesion size. The extent of the ablated area depends on factors such as the power settings, procedure duration, and electrode type [61,62]. Treatment-induced artifacts may obscure the EUS view, so RFA should be initiated from the farthest and most challenging areas of the lesion [61]. Post-procedurally, CH-EUS can be used to assess the residual neoplastic tissue and the need for further ablation.

Efficacy and safety

Table 3 summarizes the results of previous studies of EUS-RFA for PNETs [15,39,42,60,61,63–68]. The pooled clinical success rates were 98.2% and 86.5%, and the pooled AE rates were 18.6% and 18.2% for F-PNETs and NF-PNETs, respectively.

In a recent meta-analysis of 11 studies involving 292 patients, the technical success rate was 99.2%, with a complete radiological response rate of 87.1% for EUS-RFA in the treatment of PNETs [59]. The overall rate of AEs was 20.0%, but the incidence of severe AEs was very low (0.9%) [59]. These findings are similar to those presented in a systematic review by Imperatore et al. [69], who reported an overall effectiveness of 96% in 61 patients during a mean follow-up of 11 months; only mild AEs occurred, at a rate of 13.7%. PNETs < 15 mm are reportedly associated with a very favorable outcome of EUS-RFA [59].

An interesting characteristic of EUS-RFA is the delayed response: Dancour et al. [65] reported complete responses in nine lesions after 6 months and in all 12 lesions after 1 year (64.2% and 85.7% response rates, respectively). Marx et al. [68] reported that in one patient, the initial radiological evaluation revealed partial treatment success (70% of the lesion), but complete necrosis was confirmed by two consecutive abdominal CT scans after 12 and 18 months of follow-up. This kind of delayed response suggests radiofrequency- induced immunomodulation, most likely by fostering antigen presentation to lymphocytes and promoting systemic antitumor immunity [70].

Several studies have explored the safety profile of EUS-RFA: the most common complications were abdominal pain and acute pancreatitis. However, Barthet et al. [64] found that among 12 patients with NF-PNETs, two experienced major AEs, including acute pancreatitis with early infection, possibly due to overtreatment, in one patient and pneumoperitoneum with a fluid collection subsequently treated with surgical exploration in the other. Marx et al. [42,68] recently published a retrospective study of 27 patients with NF-PNET and 7 patients with insulinoma across two centers: serious AEs included pancreatitis, necrosis, and mortality. One 97-year-old patient with multiple co-morbidities initially underwent EUS-RFA; the treatment was clinically successful but the patient developed a retrogastric collection 2 weeks later and died after 2 weeks of supportive care.

EUS-RFA effectively induces coagulative necrosis within lesions, but its heat-based mode of operation poses risks of complications such as bleeding, intestinal adhesions, acute pancreatitis, and stenosis of the main pancreatic duct. To date, the risk factors for AEs following EUS-RFA have not been adequately identified. In the study by Crinò et al. [18], the distance between the lesion and the main pancreatic duct in eight of nine patients with post-RFA pancreatitis was ≤ 2 mm. Thus, prophylactic ductal stenting may be advisable to reduce the risk of ductal strictures or pancreatitis, but the protective role of ductal stenting in RFA requires further investigation. Imaging within 24–72 hours after RFA can help confirm the size of the achieved coagulative necrosis and assist in managing post-procedural complications.

A retrospective propensity-matching analysis comparing EUS-RFA and surgical resection in the treatment of insulinoma revealed a clinical efficacy of 100% after surgery and 95.5% after EUS-RFA (p = 0.160) [18]. The incidence of AEs was 18.0% after EUS-RFA and 61.8% after surgery (p < 0.001), with severe AEs developing in 15.7% of patients after surgery but in none after EUS-RFA. That study reported significantly higher recurrence-free survival in patients treated with surgical resection (p < 0.0001); 15 lesions (16.9%) recurred after EUS-RFA and were treated by repeat RFA (11 patients) or surgical resection (4 patients) [18].

No prospective studies have directly compared EUS-EA and EUS-RFA outcomes. In their meta-analysis of the management of PNETs, Garg et al. [40] evaluated 13 studies in which patients were treated with EUS-RFA and 7 in which they were treated with EUS-EA. The clinical success rates were similar at 85.2% and 82.2%, respectively. The rates of AEs were also comparable, 14.1% for EUS-RFA and 11.5% for EUS-EA, indicating no significant differences in the effectiveness or safety of the two techniques. The most common AE was pancreatitis, which occurred in 7.8% of patients treated with EUS-RFA and in 7.6% of those treated with EUS-EA.

CONCLUSION

EUS has become an indispensable tool in the diagnosis and treatment of PNETs. Its contrast-enhanced harmonic imaging has improved both the detection of PNETs and differential diagnosis. EUS-guided biopsy provides essential information for histological diagnosis and tumor grading.

The management of PNETs should encompass factors such as tumor grade, patient characteristics, and patient quality of life. EUS-guided local ablative therapy offers a less invasive alternative to surgery in high-risk patients with small (< 2 cm) grade 1 PNETs. A step-up approach involving EUS-guided ablation followed by surgery in patients with treatment failure may also be a valid option. Further prospective studies focusing on long-term survival and recurrence after local ablation are necessary.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Yun Je Song: resources, data curation, writing - original draft, visualization; Jun Kyeong Lim: resources, data curation, visualization; Jun-Ho Choi: conceptualization, methodology, writing - review & editing, supervision

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

None