Increased risk of dementia in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort study

Article information

Abstract

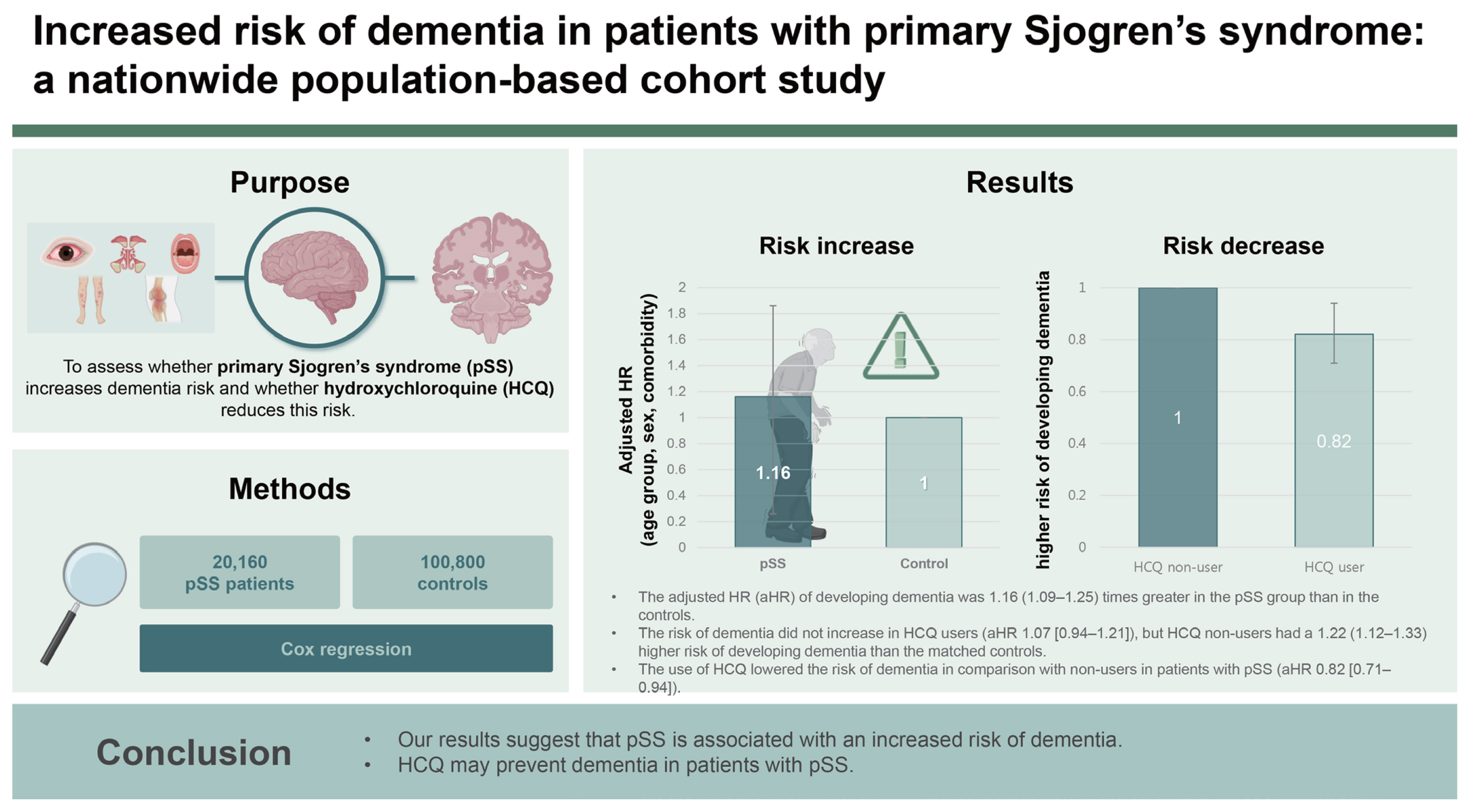

Background/Aims

This nationwide cohort study aimed to evaluate (1) whether primary Sjogren’s syndrome (pSS) can contribute to the development of dementia and (2) whether the use of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) can decrease the incidence of dementia in patients with pSS using the Health Insurance Review and Assessment database.

Methods

We established a cohort between 2008 and 2020 of 20,160 patients with pSS without a history of dementia. The control group comprised sex- and age-matched individuals with no history of autoimmune disease or dementia. Cox proportional hazard analyses were performed to identify the association between pSS and dementia development. We also assessed the hazard ratio (HR) of dementia in early users of HCQ (within 180 days of the diagnosis of pSS) compared to non-users, adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities.

Results

The incidence of dementia was 0.68 (95% CI 0.64–0.72) cases per 100 person-years in pSS, and it was 0.58 (0.56–0.60) in the controls. The adjusted HR (aHR) of developing dementia was 1.16 (1.09–1.25) times greater in the pSS group than in the controls. The risk of dementia did not increase in HCQ users (aHR 1.07 [0.94–1.21]), but HCQ non-users had a 1.22 (1.12–1.33) higher risk of developing dementia than the matched controls. The use of HCQ lowered the risk of dementia in comparison with non-users in patients with pSS (aHR 0.82 [0.71–0.94]).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that pSS is associated with an increased risk of dementia. HCQ may prevent dementia in patients with pSS.

INTRODUCTION

Primary Sjogren’s syndrome (pSS) is a common chronic autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands [1]. It often extends beyond glandular manifestations to affect various systems, including the vascular, nervous, pulmonary, and renal systems [2]. Neurological complications of the central nervous system, such as cognitive dysfunction and dementia, are widely reported, with prevalence rates ranging from 8% to 49% in patients with pSS [3].

Dementia has emerged as the most common neurodegenerative disease that threatens health, with a high incidence rate, serious socioeconomic burden, and irreversible neuronal damage to the brain [4]. However, the role of neuroinflammation in dementia remains controversial. Vasculitis, autoantibodies, immune complex deposition, and cellular inflammation are potential mechanisms through which pSS increases the likelihood of developing dementia, leading to nerve damage, cognitive decline, and dementia onset. A recent meta-analysis revealed a significant increase in the risk of dementia in individuals with pSS [5]. Nevertheless, four of the five studies were conducted in only one country, raising the need for research in diverse settings.

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is commonly used in patients with pSS. Recently, Varma et al. showed that the initiation of HCQ was associated with a reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) compared with methotrexate initiation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [6]. This finding was consistent across four distinct analysis schemes designed to address specific types of bias, including informative censoring, reverse causality, and outcome misclassification. They also showed that HCQ rescued impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity in an APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model of AD and corrected multiple molecular abnormalities [6]. In contrast, a cohort study utilizing a UK primary care database found no association between HCQ exposure in patients with connective tissue disease (CTD) and the risk of AD; however, only a limited number of patients with pSS were included [7]. The association between HCQ and the primary prevention of dementia in patients with pSS has not been well established.

Hence, this nationwide population-based cohort study aimed to investigate (1) whether pSS can contribute to the development of dementia and (2) whether the use of HCQ can decrease the incidence of dementia in patients with pSS, using the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) database.

METHODS

Data source

We used HIRA, the nationwide claims database of in South Korea. The National Health Insurance is a universal health coverage system that covers almost 100% of all Korean residents. A national health insurance corporation, the HIRA has a database that covers all medical claims in South Korea [8]. The database contains demographic information, diagnoses determined using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), procedure codes, and prescription records. Data were removed from the HIRA patient records in accordance with the Personal Information Protection Act of South Korea. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, with a waiver of informed consent (IRB number: 2023-03-002).

Study design and population

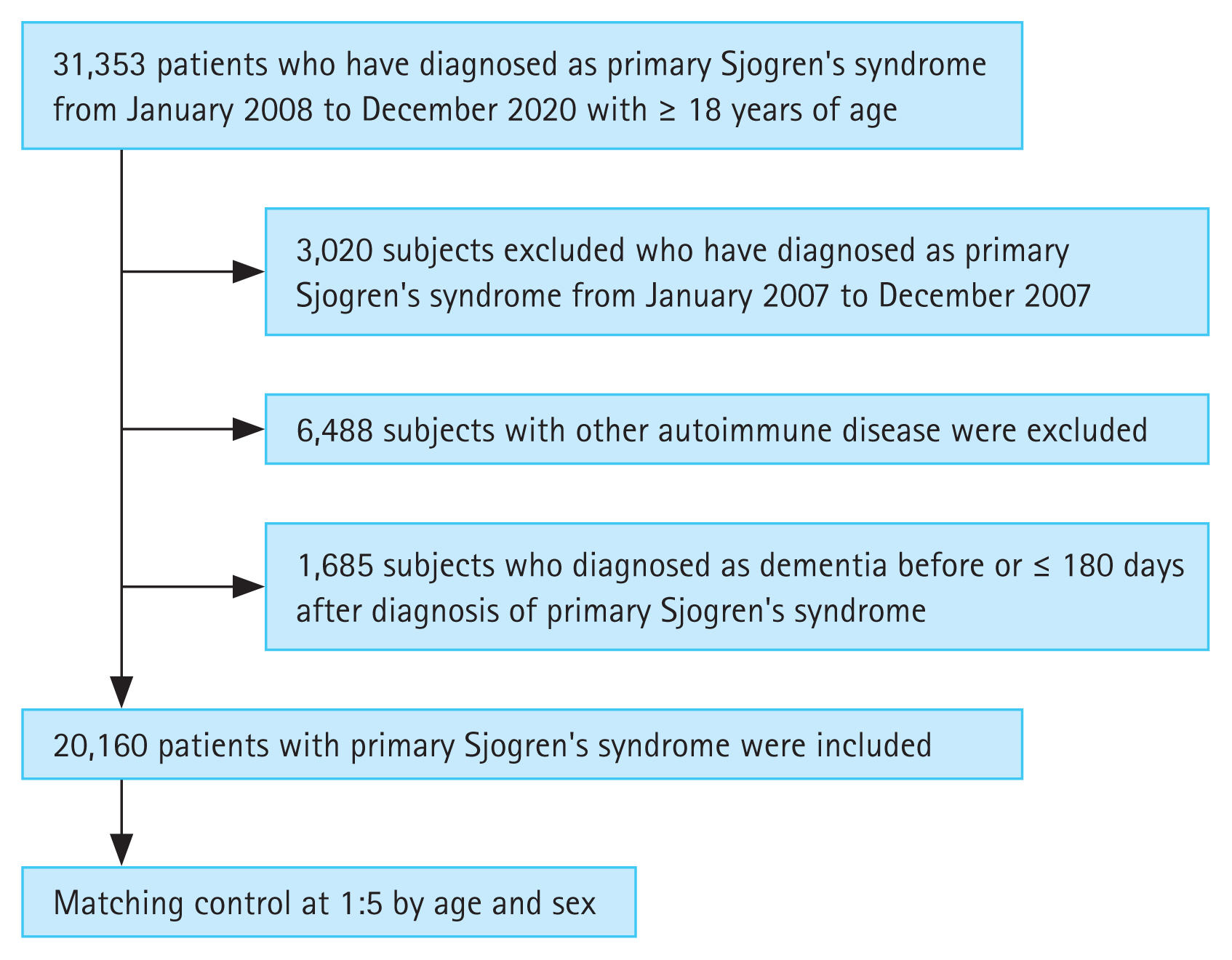

A total of 31,353 patients with pSS aged ≥ 18 years were identified in the claims data from January 2008 to December 2020 (Fig. 1). To prevent the inclusion of patients previously diagnosed with pSS, we set a washout period. Therefore, patients diagnosed with pSS before 2008 (n = 3,020) were excluded. The case definition for pSS required more than one visit based on the pSS ICD-10 diagnostic codes of M35.0, and registration with the National Rare Intractable Disease Supporting Program (code V139). Since January 2006, patients with rare and incurable diseases have been registered in the Individual Copayment Beneficiaries Program (ICBP) to reduce the burden of medical expenses in South Korea since January 2006 [9]. After registration in this program, the financial burden for patients with rare and incurable diseases has been reduced, with patients paying 10% of healthcare costs as co-payments [9,10]. The application of ICBP for pSS requires a thorough clinical, laboratory, and pathologic evaluation that fulfills the American-European Consensus Group (AECG) classification criteria for pSS [11]. The National Health Insurance Service reviewed the documents written by doctors to meet the classification criteria, and codes for rare and incurable diseases were allocated to the patients.

Patients with any other rheumatic diseases (RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, Takayasu’s arteritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, polymyositis, dermatomyositis, mixed CTD, ankylosing spondylitis, sarcoidosis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and Bechet’s disease), hepatitis C, or lymphoma based on the ICD-10 diagnostic codes and codes of the National Rare Intractable Disease Support Program were excluded (n = 6,488). Patients with a history of dementia before the diagnosis of pSS or dementia that occurred within six months of the diagnosis of pSS were excluded (n = 1,685). Ultimately, 20,160 patients were included in the pSS group. The control group included age- and sex-matched participants diagnosed with pSS at the index date in a 1:5 ratio with the general population without a history of any rheumatic diseases, including pSS and dementia. Each patient was followed-up after the index date until the first diagnosis of any type of dementia, death, or the end of the study (December 31, 2021).

Outcomes and relevant variables

The primary outcome of this study was the incidence of newly diagnosed dementia in patients with pSS and in a matched cohort. Patients with dementia were defined as those who were prescribed anti-dementia drugs (donepezil, memantine, rivastigmine, or galantamine) at least once using the ICD-10 diagnosis codes (F00–F03, G30). According to the Korean National Health Insurance regulatory standards, anti-dementia drug prescriptions are reimbursed only for the cases with explicit documentation of clinical cognitive assessment: Mini-Mental State Examination score ≤ 26, and Clinical Dementia Rating 1–3 or Global Deterioration Scale stage 3–7 [12]. Matching covariates were age, sex, and major comorbidities, such as diabetes (E10–E14), hypertension (I10–I15), heart failure (I50), ischemic heart disease (I20–25), stroke (I60–64), and major psychosis (F20–F29). The use of HCQ prescribed within 180 days of the diagnosis of pSS was investigated to determine its preventive role against dementia in patients with pSS.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the patients in both groups are presented as numbers with percentages (%) for categorical variables and as means with standard deviations for continuous variables. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare clinical characteristics between the two groups. A Cox proportional hazards regression model for matched data after adjusting for sex, age, and comorbidities was used to evaluate the relative hazard for events in the pSS group, considering the control group as a reference. The relative hazards were presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We also performed Cox proportional hazard analysis to identify the association between HCQ use and the development of dementia. All statistical analyses were performed using R 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and a two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

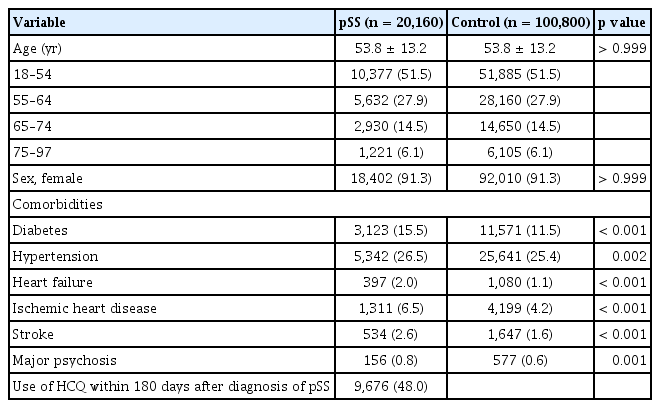

Baseline characteristics

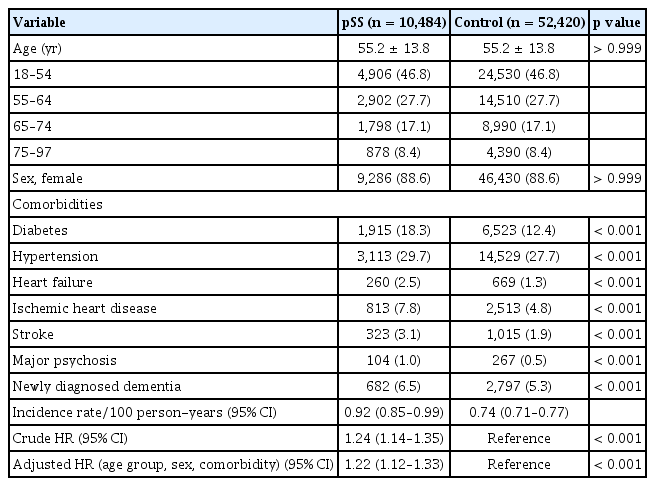

We identified 20,160 patients with pSS and 100,800 matched controls. The baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the enrolled population was 58.8 ± 13.2 years, and the proportion of females was 91.3%. The prevalence of diabetes (15.5% vs. 11.5%), hypertension (26.5% vs. 25.4%), heart failure (2.0% vs. 1.1%), ischemic heart disease (6.5% vs. 4.2%), stroke (2.6% vs. 1.6%), and major psychosis (0.8% vs. 0.6%) were significantly higher in patients with pSS than in the controls, although the age and sex ratios of the two groups were the same. Among patients with pSS, 9,676 (48.0%) were exposed to HCQ within 180 days of the diagnosis of pSS.

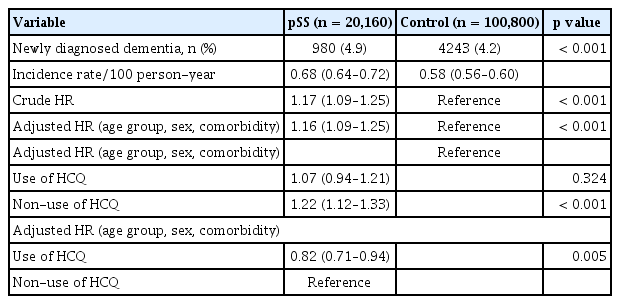

pSS and risk of dementia

The incidence of newly diagnosed dementia in the pSS group was 0.68 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 0.64–0.72) and in the controls was 0.58 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 0.56–0.60) (Table 2). Patients in the pSS group had an increased risk of dementia compared to those in the control group (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.09–1.25). Even when adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities, adjusted HR was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.09–1.25), indicating an increased risk of dementia in patients with pSS.

Early HCQ treatment and risk of dementia in patients with pSS

We evaluated whether early HCQ treatment (within 180 days of pSS diagnosis) affected the incidence of dementia in patients with pSS. Compared to the total individuals in the control group, the HR of early HCQ treatment was slightly lower (adjusted HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00–1.24) than that of non-exposure to HCQ (adjusted HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.13–1.36) in the pSS group. Early exposure to HCQ was associated with reduced risk of dementia (adjusted HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.73–0.95) in comparison with non-HCQ users.

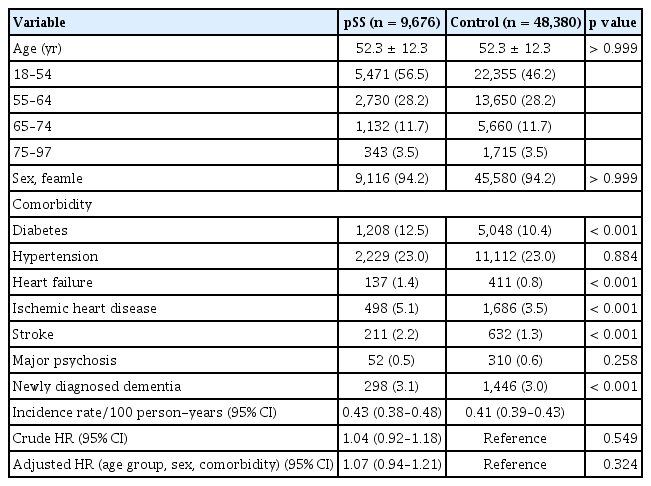

Next, we divided pSS patients into two groups: those who received early HCQ treatment and those who did not. We then conducted a comparative analysis with age- and sex-matched controls (Table 3, 4). The pSS group with early HCQ treatment did not have a higher risk of dementia compared to the control group, with an adjusted HR of 1.07 (95% CI, 0.94–1.21) after adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidities. In contrast, the pSS group without early HCQ treatment had a significantly higher risk of dementia compared to the control group, even after adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidities (adjusted HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.12–1.33).

Baseline characteristics and dementia risk of patients with pSS on early HCQ treatment versus age- and sex-matched non-pSS cohort

DISCUSSION

In the present population-based cohort study, the incidence rate for dementia in patients with pSS was 0.68 per 100 person-years, and pSS was significantly associated with an increased risk of dementia. Early exposure to HCQ is associated with a lower risk of dementia in patients with pSS.

Several epidemiological studies have evaluated the association between pSS and the risk of developing dementia. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that the risk of dementia was 1.24 times higher in SS (95% CI: 1.15–1.33) [5]. Nevertheless, four of the five studies included in the analysis were conducted in Taiwan, potentially introducing geographical bias and a relatively significant overlap in the study samples [13–16]. Therefore, we analyzed the association between pSS and dementia using HIRA data, which was consistent with the results of previous studies conducted in Taiwan. We added a prescription code for anti-dementia medication to the operational definition of dementia to increase the reliability of the diagnosis. In South Korea’s Health Insurance System, hospitals can receive medical expenses for anti-dementia drugs after evaluation of medical records, including the Mini-Mental State Examination and Global Deterioration Scale score or Clinical Dementia Rating score, and approval of the HIRA. Therefore, it was considered that the possibility of falsely coding dementia would be low, and that patients with moderate to high degrees of dementia would be included more often than those with mild cognitive impairment. Recent studies have demonstrated that the upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines plays multiple roles in neurodegeneration [17]. However, the risk for dementia does not appear to increase in all autoimmune diseases. A recent meta-analysis showed that pSS (pooled relative risk, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.14–1.39) and systemic lupus erythematosus (pooled relative risk, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.19–1.73) were related to elevated risk of dementia, but no relationship between RA and risk of dementia was found [18]. A Mendelian randomization study showed an association between pSS, multiple sclerosis, and AD among seven autoimmune diseases [19]. Therefore, further studies are required to understand how disease-specific pathogenesis contributes to dementia development.

Research on the pathophysiology of AD has revealed that autophagy disruption plays a role in the build-up of protein aggregates [20]. One possible mechanism by which HCQ lowers the risk of dementia is as follows. Experimental findings indicate that the degradation of amyloid plaques is inhibited by autophagy-blocking substances such as HCQ [7,20]. In the Drug Repurposing for Effective Alzheimer’s Medicines study, the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway was identified as a potential drug target for pharmacoepidemiological analysis due to its involvement in cytokine signaling [21]. Varma et al. [6] showed that HCQ initiation was associated with a lower risk of incident AD than methotrexate initiation in patients with RA.

Moreover, they demonstrated that HCQ rescues impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity in APP/PS1 transgenic mice and corrects multiple molecular abnormalities underlying AD, such as neuroinflammation, Aβ clearance, and tau phosphorylation underlying AD through inactivation of STAT3 [6]. However, contradictory results have been previously reported. In 2001, an 18-month randomized, placebo-controlled trial, and the results of the study showed no effect of HCQ against placebo on the progression of dementia in patients with early AD [22]. The Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database found that HCQ, methotrexate, and sulfasalazine increased the risk of AD in patients with RA, rather than providing protection. A cohort study conducted in the UK reported that the long-term use of HCQ in patients with CTD was not associated with a decreased risk of AD compared to non-use of HCQ [7]. Although our study showed a preventive effect of HCQ against dementia in patients with pSS, caution should be exercised. To date, no randomized controlled trials have assessed the effect of HCQ on the primary prevention of dementia. The absence of trials is due to the requirement for extended study durations spanning several years and the necessity of recruiting a substantial number of participants to yield significant and meaningful outcomes. In the absence of such evidence, larger observational studies are needed to explore the effect of HCQ on dementia prevention, considering the timing and duration of HCQ use for each specific disease rather than all CTDs.

In this study, 48% of patients with pSS used HCQ within 6 months of diagnosis, a figure that was higher than expected. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommendations for the management of Sjögren’s syndrome suggest the use of HCQ only for frequent episodes of acute musculoskeletal pain [23]. However, Fauchais et al. [24] reported that HCQ is used by more than half of patients with arthralgia in real-life settings. Similarly, a Chinese multicenter registration study reported that HCQ, the most frequently prescribed drug for pSS, was used by 67.5% of patients [25]. No disease-modifying drugs are currently available for pSS. Among the available therapeutic options, HCQ stands out for its good safety profile and minimal side effects [26]. Therefore, the high prescription rate of HCQ in clinical practice deviates from the recommendations.

We also found that patients with pSS were more likely to have cardiovascular (CV) comorbidities and risk factors than those without pSS. We included patients with mixed dementia because autopsy studies have reported prevalence of mixed Vascular-Alzheimer Dementia as 20–22%. Moreover, in clinical practice, the distinction between AD and vascular dementia is complex owing to their overlapping clinical presentation [27]. Therefore, evaluation and management of CV risk factors should be considered in patients with pSS. HCQ has been shown to exert beneficial effects on the metabolic and CV outcomes in patients with RA [28]. This effect is achieved through the reduction of modifiable risk factors for CV disease, such as the decreased incidence of diabetes. A UK cohort study demonstrated that chronic exposure to HCQ is associated with a lower mortality risk in patients with CTD [7]. However, whether HCQ can reduce vascular dementia through metabolic and CV improvements remains unclear.

This study has some limitations. First, because this retrospective study was based on a claims database, medical chart review was not possible. Other factors, such as disease activity and severity of pSS, laboratory findings such as inflammatory markers, autoantibody profiles, and risk factors for dementia, such as family history, smoking, alcohol use, or level of education, could not be considered. Secondly, the dose, duration, and adherence to HCQ were not investigated. All individuals were classified as HCQ users or non-users based on their HCQ use within 6 months after the diagnosis of pSS. Finally, drug-related effects other than those of HCQ, including those of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, and immunosuppressive agents, were not evaluated.

Numerous brain regions exhibit a high density of glucocorticoid receptors, and the prolonged elevation of endogenous glucocorticoid levels may induce neurotoxicity, thereby increasing the risk of cognitive decline and dementia. However, a recent systematic review revealed that individuals on long-term glucocorticoids tended to exhibit notably poorer executive function, particularly working memory and global cognitive function. Nevertheless, most studies of dementia (both all-cause dementia and AD) indicated either null or negative associations with glucocorticoid use, suggesting a potential protective effect. Therefore, although glucocorticoid therapy in individuals with inflammatory conditions may adversely affect their specific cognitive function and brain structures, it could also substantially decrease the risk of dementia [29]. Considering the pivotal role of the immune/inflammatory response in the development of AD, preclinical studies suggest that immunomodulatory agents such as calcineurin inhibitors could potentially modify dementia progression [30]. Therefore, owing to the lack of information on various risk factors for dementia, including education, physical activity, smoking, and the use of medications such as glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants, these limitations could impact the results, particularly the potential for bias. Thus, further studies that include more detailed data on risk factors and medications are needed to validate our findings.

In conclusion, using nationwide claims data, we found that pSS is independently associated with the development of dementia. Thus, HCQ may prevent dementia in patients with pSS.

KEY MESSAGE

1. In the present population-based cohort study, pSS was significantly associated with an increased risk of dementia.

2. Early exposure to HCQ is associated with a lower risk of dementia in patients with pSS.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Kyung Ann Lee: conceptualization, data curation, validation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, visualization; Hyeji Jeon: investigation, data curation; Hyun-Sook Kim: investigation; Kyomin Choi: writing - review & editing; Gi Hyeon Seo: conceptualization, methodology, resources, data curation, formal analysis, writing - review & editing, supervision

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

This study was supported by funds from Soonchunhyang University.