Reclassification of the overlap syndrome of Behçet’s disease and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis in patients with Behçet’s disease

Article information

Abstract

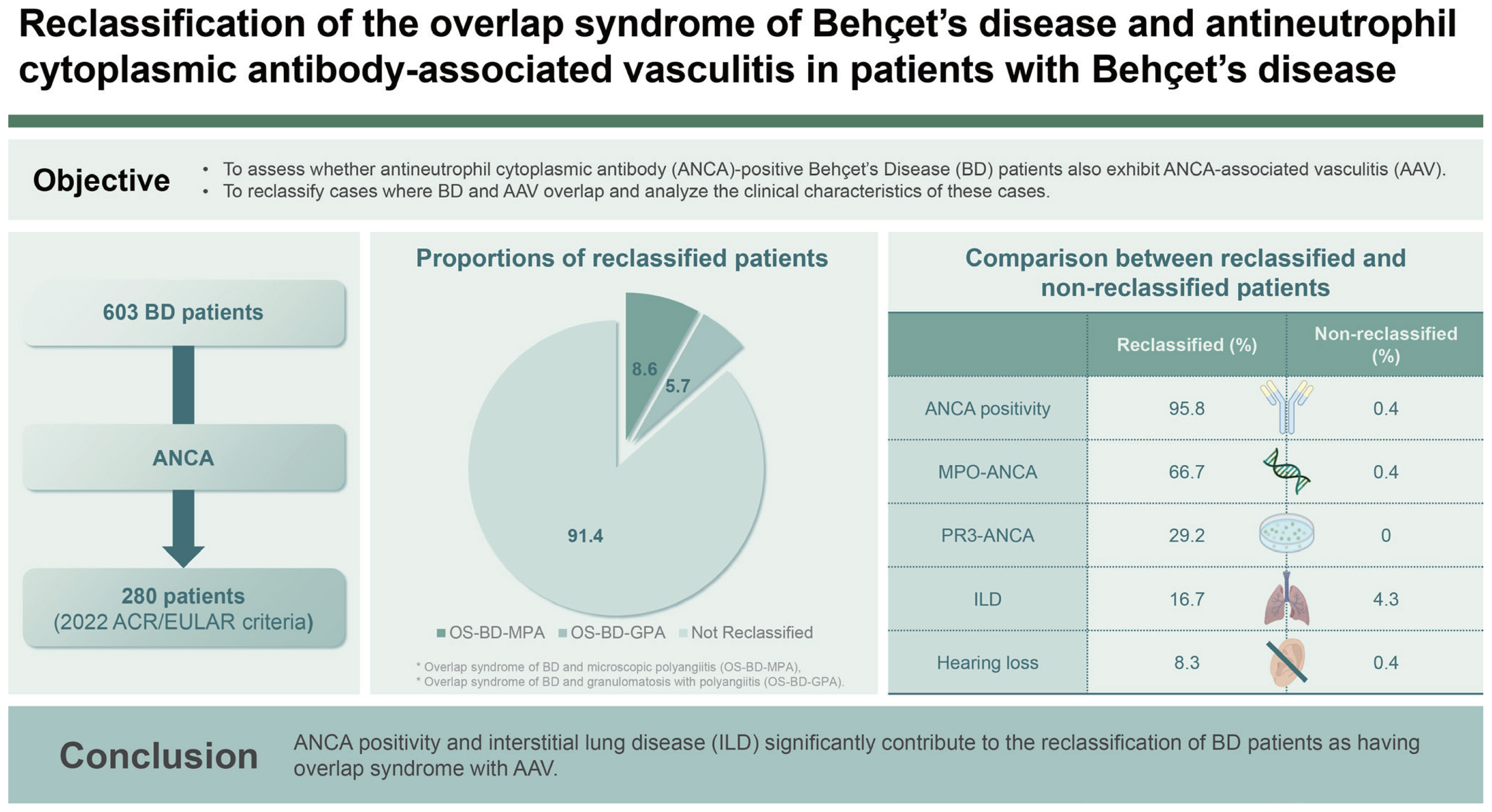

Background/Aims

This study applied the 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (ACR/EULAR) criteria for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) to patients with Behçet’s disease (BD) to investigate the proportion and clinical implications of the reclassification to the overlap syndrome of BD and AAV (OS-BD-AAV).

Methods

We included 280 BD patients presenting with ANCA positivity but without medical conditions mimicking AAV at diagnosis. Demographic data, items from the 2014 revised International Criteria for BD and 2022 American College of Rheumatology and European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria for AAV, ANCA positivity, and laboratory results were recorded as clinical data at diagnosis. A total score ≥ 5 indicated microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), whereas a total score ≥ 6 indicated a diagnosis of eosinophilic GPA (EGPA).

Results

The overall reclassification rate of OS-BD-AAV was 8.6%. Of the 280 patients, 16 (5.7%) and 8 (2.9%) were reclassified as having OS-BD-MPA and OS-BD-GPA, respectively; none were classified as having OS-BD-EGPA. ANCA, myeloperoxidase-ANCA (P-ANCA), proteinase 3-ANCA (C-ANCA) positivity, hearing loss, and interstitial lung disease (ILD) at diagnosis were more common in patients with OS-BD-AAV than in those without. ANCA positivity and ILD at BD diagnosis contributed to the reclassification of OS-BD-AAV. However, hearing loss was not considered a major contributor to BD due to its possibility of developing as a manifestation of BD.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the reclassification rate (8.6%) of patients with BD and ANCA results at diagnosis as OS-BD-AAV.

INTRODUCTION

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a variable vessel vasculitis that can affect arteries and veins, ranging from small to large vessels. It is characterised by recurrent oral and/or genital aphthous ulcers accompanied by various clinical manifestations in the skin, eyes, joints, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system (CNS) [1]. According to the criteria proposed by the International Study Group (ISG) in 1990 (the 1990 ISG criteria for BD), BD can be diagnosed based on the presence of recurrent oral ulcers concurrent with two of the following four symptoms: genital ulcers, cutaneous lesions, ocular lesions, and a positive pathergy test [2]. However, the many limitations of the 1990 ISG criteria have prompted the need for new criteria for BD in clinical practice. These limitations include the requirement for differential diagnoses of oral and genital aphthous ulcers from diverse medical conditions, items of overestimated oral aphthous ulcers while underestimating ocular lesions, and lack of inclusion of vascular and nervous systemic involvement in BD [3].

In 2014, the International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for BD proposed the revised International Criteria for BD (the 2014 revised ICBD criteria). The 2014 revised ICBD criteria assigned two points to the three items of oral aphthosis, genital aphthosis, and ocular lesions, whereas one point was assigned to the three remaining items of skin manifestations, vascular lesions, and neurological manifestations. Except for a positive pathergy test, BD can be diagnosed in patients with a total score ≥ 4 [4]. In the pathogenesis of BD, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B51 has been reported to have an odds ratio for BD development as high as 3.49, indicating genetic susceptibility. Furthermore, immunological dysregulation, T-cell hypersensitivity, and neutrophil hyperactivation are known to play critical roles [5,6].

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) is a group of autoimmune antibodies targeting neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantigens, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and proteinase 3 (PR3) [7,8]. The presence of ANCA does not always indicate the possibility of ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV). When ANCA provokes AAV, it is termed pathogenic ANCA; otherwise, it is known as natural ANCA [7,9]. AAV is a small-vessel vasculitis characterised by few or no immune complexes with fibrinoid necrotic deposits on biopsy. AAV has three subtypes: microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and eosinophilic GPA (EGPA) [1,10].

To date, several studies have elucidated the detection rate and clinical implications of ANCA positivity in patients with BD, whereas several case series have reported the identification of patients with BD accompanied by AAV [11–13]. Given the size of vessels affected by BD, as well as the possibility of ANCA production through the hyperactivation of neutrophils in BD pathogenesis, we hypothesised that BD may trigger the production of ANCA and may be accompanied by AAV. Additionally, we assumed that a definite diagnosis of BD might discourage physicians from recognising and identifying AAV in patients with BD, regardless of ANCA positivity.

New classification criteria for MPA, GPA, and EGPA were proposed by the American College of Rheumatology and European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology in 2022 (the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria) [14–16]. Despite some limitations, compared with previous criteria, these criteria assign differently weighted scores to various clinical manifestations and ANCA positivity based on AAV subtypes. This approach enhances the AAV classification rate and reduces the likelihood of missed diagnosis [17]. Therefore, the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria are expected to be more efficient in identifying AAV and further reclassifying the overlap syndrome of BD and AAV (OS-BD-AAV) in patients with BD than the previous criteria for AAV. However, no study has yet investigated the identification of AAV and reclassification of OS-BD-AAV in a substantial number of patients with BD according to the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV. Hence, in the present study, we applied the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV in patients with BD who met both the 1990 ISG and the 2014 revised ICBD criteria. Subsequently, we investigated the proportions and clinical implications of the reclassification of OS-BD-AAV.

METHODS

Study population

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 603 patients diagnosed with BD according to the 1990 ISG criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) initial classification of BD at the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, from March 2005 to December 2022; ii) availability of well-documented medical records sufficient for collecting clinical data at BD diagnosis or during follow-up; iii) fulfilment of the 2014 revised ICBD criteria; iv) availability of ANCA tests results within 3 months before and after the diagnosis of BD; v) absence of concomitant malignancies or serious infectious diseases [18,19]; vi) absence of concomitant autoimmune diseases, such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or primary sclerosing cholangitis, that could affect ANCA false positivity [20]; vii) no drug history affecting ANCA false positivity, such as propylthiouracil [21]; and viii) no administration of glucocorticoids or immunosuppressive drugs before the ANCA tests.

Among the 603 patients with BD, 33 were excluded owing to non-fulfilment of the 2014 ICBD criteria, and 279 were excluded owing to the absence of ANCA test results within 3 months before or after BD diagnosis. Furthermore, among the remaining 291 patients with BD, 1, 7, 2, and 1 were excluded due to concomitant malignancies, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis, respectively. As a result, 280 patients with BD were included because BD, presumed to be a systemic vasculitis, was postulated to manifest signs indicative of small- or medium-vessel vasculitis (Fig. 1).

Ethical disclosure

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Severance Hospital (Seoul, Korea; IRB No. 2023-0220-001). Given the retrospective design of the study and the use of anonymised patient data, the requirement for written informed consent was waived by the IRB.

Clinical data

Age and sex were collected as demographic data at the time of BD diagnosis. The number of patients who met the 2014 ICBD criteria was also assessed. Additionally, the number of patients fulfilling the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV was evaluated. In the present study, ANCA testing included indirect immunofluorescence assay (perinuclear [P]-ANCA and cytoplasmic [C]-ANCA) or immunoassay (MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA). The results of ANCA and routine laboratory tests at BD diagnosis, medications administered, and poor outcomes during follow-up are presented in Table 1. End-stage kidney disease (ESKD), cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) were all classified as poor outcomes.

2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV

The 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria have two major considerations. The first is the essential need for evidence of small-and medium-vessel vasculitis, whereas the second is the mandatory exclusion of medical conditions that mimic AAV [14–16]. Of these two considerations, because BD may affect almost all vessels from small to large as a variable vessel vasculitis, additional signs or symptoms suggestive of smallor medium-vessel vasculitis were not required. Additionally, patients with concomitant medical conditions were excluded, as shown in Figure 1. A total score ≥ 5 is necessary for classifying MPA and GPA, whereas a total score ≥ 6 is needed to diagnose EGPA [14–16].

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous and categorical variables are expressed as median (interquartile range) and number (percentage), respectively. Significant differences between categorical and continuous variables were compared using the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests and the Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients with BD

The median age of the 280 patients diagnosed with BD was 56.0 years, with 31.1% being male. Among the items of the 2014 revised ICBD criteria, the most frequently observed clinical manifestation was oral aphthous ulcers (91.8%), followed by genital aphthous ulcers (61.4%) and skin manifestations (43.9%). Among the eight patients exhibiting vascular manifestations, seven had aortic valve regurgitation, and one had deep vein thrombosis. The pathergy test was performed in 72 of the 280 patients with BD, revealing positive results in 12 patients (16.7%). The positivity rate aligned closely with the 15.4% previously reported among 3,497 Korean patients with BD [22]. In addition, 70 of the 280 patients with BD (25.0%) tested positive for HLA-B51. ANCA was detected in 24 (8.6%) patients with BD, with 17 (6.1%) having MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) and 7 (2.5%) having PR3-ANCA (C-ANCA). Among the items of the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV, apart from ANCA positivity, regarding the clinical section, 20, 5, 3, and 2 patients exhibited obstructive airway disease, nasal involvement, mononeuritis multiplex, and hearing loss, respectively. Eighteen patients had haematuria, and only one exhibited serum eosinophil ≥ 1,000/μL. Granulomatosis and eosinophilic extravasation were confirmed on biopsy in four and one patients, respectively; however, pauci-immune glomerulonephritis was not observed on biopsy. Regarding radiological features, 33 patients had pulmonary nodules, 15 had interstitial lung disease (ILD), and 6 exhibited paranasal sinusitis. The remaining laboratory results, medications administered, and development of poor outcomes during the follow-up are presented in Table 1.

Application of the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for MPA to patients with BD

Of the 280 patients with BD, 17 and 15 received +6, and +3 scores owing to MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) positivity and pulmonary fibrosis or ILD on chest imaging, respectively. Conversely, seven, five, and one received scores of −1, −3, and −4 owing to PR3-ANCA (or C-ANCA) positivity, nasal involvement, and peripheral eosinophilia, respectively. Ultimately, 16 (5.7%) patients achieved a total score of 5 or more and could therefore be reclassified as having OS-BD-MPA (Table 2).

Application of the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for GPA to patients with BD

Of the 280 patients with BD, 5 and 2 received scores of +3 and +1 owing to nasal involvement and hearing loss, respectively. Additionally, 33, 7, 6, and 4 patients with BD exhibited pulmonary nodules (+2), PR3-ANCA (or C-ANCA) positivity (+5), paranasal sinusitis (+1), and granulomatosis on biopsy (+2), respectively. In contrast, 17 and 1 received scores of −1 and −4 owing to MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) positivity and peripheral eosinophilia, respectively. At last, eight (2.9%) patients achieved a total score ≥5 and were therefore reclassified as having OS-BD-GPA (Table 3).

Application of the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for EGPA to patients with BD

Of the 280 patients with BD, 20, 3, 1, and 1 received +3, +1, +5, and +2 scores owing to obstructive airway disease, mononeuritis multiplex, peripheral eosinophilia, and eosinophilic extravasation on biopsy, respectively. In contrast, 18 and 7 patients received scores of −1 and −3 owing to haematuria and PR3-ANCA (or C-ANCA) positivity, respectively. Summing all the scores received, none of the patients with BD could be reclassified as having OS-BD-EGPA (Table 4).

Comparison of the variables between patients with OS-BD-AAV and those without

Of the 280 patients with BD, 24 (8.6%) were reclassified as having OS-BD-AAV (16 with OS-BD-MPA and 8 with OS-BD-GPA). No significant differences were observed in the demographic data of routine laboratory results at BD diagnosis and medications administered during follow-up between the two groups. Regarding the items in the 2014 revised ICBD criteria, only vascular manifestations were more commonly found in patients with OS-BD-AAV than in those without OS-BD-AAV (12.5% vs. 2.0%, p = 0.003). Patients with OS-BD-AAV had significantly higher rates of ANCA (95.8% vs. 0.4%, p <0.001), MPO-ANCAs (or P-ANCAs) (66.7% vs. 0.4%, p < 0.001), and PR3-ANCA (or C-ANCAs) (29.2% vs. 0%, p < 0.001) positivity than those without. Regarding the items of the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV, apart from ANCA positivity, hearing loss (8.3% vs. 0.4, p < 0.001) and ILD on chest imaging (16.7% vs. 4.3%, p = 0.010) were more frequently observed in patients with OS-BD-AAV than in those without. Additionally, of the 280 patients, 2, 4, and 9 patients had experienced ESKD, CVA, and ACS, respectively, during follow-up. There were no significant differences in the frequency of poor outcomes between patients with and without OS-BD-AAV (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

The revised nomenclature of vasculitides proposed by the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC) in 2012 proposed three major categories for classifying systemic vasculitides: the affected vessel size, affected organs, and underlying diseases [1]. In clinical practice, vasculitis is typically classified according to the size of the vessels affected unless distinct underlying diseases are defined or isolated major organs are involved. Accordingly, it is extremely rare for BD, which has the potential to trigger vasculitis, to vary from small vessels to the aorta, and AAV, which has the potential for vasculitis to be limited to small vessels, to be discovered simultaneously in a single patient. Nevertheless, given that vasculitides can invade small vessels and that their patho-physiology shares neutrophil activation, which may lead to ANCA production [7,8], the possibility of OS-BD-AAV cannot be totally denied.

Importantly, the 2022 ACR/EULAR classification criteria have not yet been proposed for patients diagnosed with BD. Instead, at that time, AAV was classified according to the 1990 ACR criteria, 2007 European Medicine Agency algorithm for AAV, and revised 2012 CHCC nomenclature for systemic vasculitides. According to these criteria, the patients with BD included in this study were not classified as having AAV. Therefore, at the time of BD diagnosis, these patients were accurately diagnosed with BD, regardless of the AAV diagnosis. However, we applied the 2022 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for AAV in patients definitively diagnosed with BD for two reasons. First, BD is a variable vessel vasculitis that can invade small to large vessels, potentially including clinical features of small vessel vasculitis. Second, the new ACR/EULAR classification criteria for AAV include several novel items compared with the previous criteria, as follows: i) increased weight of ANCA positivity; ii) recognition of P-ANCA and C-ANCA to the same extent as that of MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA; and iii) addition of items describing specific clinical symptoms such as ILD. Therefore, the fundamental motivation for this study was to determine the number of untreated patients with BD who would meet the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV at the time of BD diagnosis.

In the present study, we applied the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV in patients with BD who met both the 1990 ISG and 2014 revised ICBD criteria and investigated the proportion and clinical implications of the reclassification of OS-BD-AAV in patients with BD. We obtained four interesting results. First, the overall reclassification rate for OS-BD-AAV was 8.6%. Second, 16 (5.7%) and 8 (2.9%) of the 280 patients with BD were reclassified as having OS-BD-MPA and OS-BD-GPA, respectively; however, none were reclassified as having OS-BD-EGPA. Third, among the laboratory results, MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) and PR3-ANCA (or C-ANCA) positivity significantly contributed to the reclassification of OS-BD-MPA and OS-BD-GPA, respectively. Fourth, in terms of the clinical features, conductive or sensorineural hearing loss and ILD on chest imaging were more frequently observed in patients with OS-BD-AAV than in those without.

Of the 24 patients with BD who tested positive for ANCA, 17 and 7 were positive for MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) and PR3-ANCA (or C-ANCA), respectively, whereas 16 and 8 patients with BD were reclassified as having OS-BD-MPA and OS-BD-GPA, respectively. This result indicates that one of the patients with MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) was not reclassified as having MPA, whereas one of the patients without PR3-ANCA (or C-ANCA) was reclassified as having GPA. According to the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for MPA, the former patient received scores of +6 and -3 owing to MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) positivity and nasal involvement, respectively; however, the patient achieved a total score of 3, and could not be reclassified as having OS-BD-MPA. For the latter patient, scores of +3, +1, and −1 were assigned owing to nasal involvement, paranasal sinusitis, and MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) positivity, respectively, resulting in a total score of 3, insufficient for reclassification as OS-BD-GPA. The patient did not meet any item of the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for EGPA (Supplementary Table 1). According to the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for GPA, the patient received scores of +1, +2, and +2 owing to hearing loss, lung nodules on chest imaging, and granulomatosis on biopsy, respectively, and thus achieved a total score of 5, allowing reclassification as GPA (Supplementary Table 2).

ANCA was detected in 24 patients with BD; coincidentally, the same number of patients was reclassified as having OS-BD-AAV. Although not all 24 patients with ANCA were reclassified as having OS-BD-AAV (as shown in Supplementary Table 1 and 2), as most patients were reclassified, it can be said that ANCA positivity significantly contributed to the reclassification of OS-BD-AAV. Therefore, it is clear that ANCA detected in patients with BD is pathogenically involved in the initiation and activation of AAV. Previous studies have reported that ANCA was positive in 10.2% of patients with BD, and unclassifiable ANCA was also found in a minority group of patients with BD [11,23]. Additionally, another study reported that ANCA positivity in patients with BD was likely associated with vascular abnormalities in the upper extremities and visceral arteries at diagnosis [12]. However, these studies did not mention the contribution of ANCA positivity in the diagnosis of BD accompanied by AAV. Nevertheless, when recalling the case reports on OS-BD-AAV and the reasons why OS-BD-AAV cannot be overlooked, we suggest that the application of the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV in ANCA-positive patients with BD should be considered.

In terms of these two clinical manifestations, patients reclassified as having OS-BD-AAV more frequently exhibited hearing loss and pulmonary ILD than those who were not reclassified (Table 5). Hearing loss has been reported in not a few patients with BD [24,25]. In the present study, hearing loss was observed in only three patients; however, it was too small to derive clinical significance. Therefore, we concluded that hearing loss may not be a major contributing factor in the reclassification of OS-BD-AAV. It was also reported that although very rare, lung parenchymal involvement in BD might manifest as bronchiolitis obliterans, organising pneumonia, eosinophilic pneumonia, and ILD; however, it might appear more frequently because of pulmonary arterial involvement [26,27]. In the present study, unlike hearing loss, ILD was observed in a considerable number of patients, and its frequency was significantly elevated in patients who were reclassified as having OS-BD-AAV than in those who were not. Therefore, given the low frequency of ILD in patients with BD and the significant difference between the two groups, we concluded that ILD may be a sufficient major contributing factor to the reclassification of OS-BD-AAV. Taken together with the results of the comparative analysis, we concluded that ANCA positivity and ILD may significantly contribute to the reclassification of OS-BD-AAV in patients diagnosed with BD.

Although HLA-B51 was not included in the 1990 ISG or 2014 revised ICBD criteria, it is considered to play an important role in the pathogenesis of BD because of its high odds ratio for BD [28]. Previous studies have reported that HLA-B51 is present in 40.8% to 55.7% of Korean patients with BD, representing a positivity rate significantly higher than that in the general population [29,30]. Given the clinical role of HLA-B51 in the pathophysiology of BD, but not AAV, and the ethnic and geographical differences, we assumed that HLA-B51 might help to distinguish BD not accompanied by AAV from OS-BD-AAV. However, no significant difference in HLA-B51 positivity was observed between patients with OS-BD-AAV and those with BD without AAV (Table 5). Therefore, unlike ANCA positivity or ILD at BD diagnosis, HLA-B51 positivity was not a critical contributor to the differentiation between patients with OS-BD-AAV and those with BD not accompanied by AAV.

Identifying patients with OS-BD-AAV among those diagnosed with BD in clinical practice has several advantages. Given the critical aspects of these two diseases, it may have clinical implications to keep AAV features in mind in patients with BD by identifying patients with OS-BD-AAV. First, there is a discordance in the definition of severe forms of the disease between BD and AAV (MPA and GPA). Severe BD primarily includes serious conditions in the eyes, CNS (neuro- BD), gastrointestinal system, and aorta, particularly the aortic valve and adjacent ascending aorta [31]. Conversely, severe AAV mainly includes diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (DAH), rapid progressive (crescentic) glomerulonephritis (RPGN), the CNS, and peripheral NS involvement, myocarditis and/or pericarditis, and mesenteric and digital ischaemia [32,33]. If clinicians fail to recognise BD accompanied by AAV, they may miss AAV-specific and unique serious medical conditions, such as DAH, RPGN, and mesenteric ischaemia.

Second, there is a discordance in the therapeutic strategies and regimens between BD and AAV (MPA and GPA). Strategies for the treatment of BD depend on the organs involved and severity of the disease [34]. Further, strategies for the treatment of AAV consist of induction and maintenance therapeutic regimens, which also depend on AAV severity. Additionally, in terms of biological agents for severe or refractory forms of diseases, intravenous tumour necrosis factor-alpha blockers and tocilizumab along with cyclophosphamide are currently recommended for BD treatment, whereas, intravenous rituximab along with cyclophosphamide is recommended as a treatment for AAV [32,33]. If clinicians fail to recognise BD accompanied by AAV, they may not provide appropriate therapeutic strategies for AAV treatment in patients with OS-BD-AAV in addition to the usual treatment for BD.

The main strength of this study is that, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first to apply the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV and thus demonstrated the rates of major contributors to the reclassification of OS-BD-AAV in patients diagnosed with BD. Furthermore, we discuss the clinical implications of the application of these AAV criteria to patients with BD exhibiting ANCA positivity and ILD on chest imaging at BD diagnosis. Nevertheless, this study had several limitations. First, ANCA tests were not universally conducted in all 603 patients screened in this study; thus, 279 of the 603 patients with BD were excluded from this study owing to a lack of ANCA test results around the time of BD diagnosis. Second, this was a retrospective and cross-sectional analysis that applied the ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV in untreated patients with BD and investigated the frequency of OS-BD-AAV. As such, it was impossible to definitively confirm whether patients should be reclassified as having OS-BD-AAV. Additionally, because the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV had not been introduced at the time of BD diagnosis, it was impossible to provide induction treatments corresponding to the AAV treatment guidelines for patients reclassified as having OS-BD-AAV. Third, as this was a single- centre study, the immediate applicability of these results to broader clinical contexts is limited as the patient cohort may not be representative. Lastly, the follow-up duration was insufficient to investigate the influence of concurrent AAV on prognosis during follow-up in patients with BD. A prospective study with a larger cohort of patients with BD will provide more reliable information on the clinical implications of the reclassification of OS-BD-AAV. Such a study could further facilitate the dynamic process of reclassification by applying the 2022 ACR/EULAR criteria for AAV in patients newly diagnosed with BD.

In conclusion, this study marks a pioneering demonstration that a significant proportion (8.6%) of patients with BD with ANCA results at BD diagnosis could be reclassified as having OS-BD-AAV. Notably, ANCA positivity and the presence of ILD at the time of BD diagnosis contributed to this reclassification. Overall, our findings underscore the importance of heightened vigilance among physicians when patients with BD exhibit ANCA positivity or develop ILD during or after a BD diagnosis.

KEY MESSAGE

1. The overall reclassification rate for OS-BD-AAV was 8.6%.

2. Of the 280 enrolled patients, 16 (5.7%) and 8 (2.9%) were reclassified as having OS-BD-MPA and OS-BD-GPA, respectively, but none as having OS-BD-EGPA.

3. ANCA positivity and the presence of ILD contributed to the reclassification of OS-BD-AAV.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

CRedit authorship contributions

Tae Geom Lee: conceptualization, methodology, resources, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, software, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, visualization, project administration; Jang Woo Ha: conceptualization, methodology, resources, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, visualization, project administration; Jason Jungsik Song: data curation, validation, writing - review & editing, project administration; Yong-Beom Park: data curation, validation, writing - review & editing, visualization, project administration; Sang-Won Lee: conceptualization, methodology, resources, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, software, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition

Funding

This study received funding from CELLTRION PHARM, Inc. Chungcheongbuk- do, Republic of Korea (NCR 2019-6), and Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical Corp, Seoul, Republic of Korea. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication. All authors declare no other competing interests.