The characteristics of Korean elderly multiple myeloma patients aged 80 years or over

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Multiple myeloma (MM) predominantly affects elderly individuals, but studies on older patients with MM are limited. The clinical characteristics and survival outcomes of patients with MM aged 80 years or over were retrospectively analyzed.

Methods

This retrospective multicenter study was conducted to investigate the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and survival outcomes of patients aged 80 years or over who were newly diagnosed with MM at five academic hospitals in Daegu, Korea, between 2010 and 2019.

Results

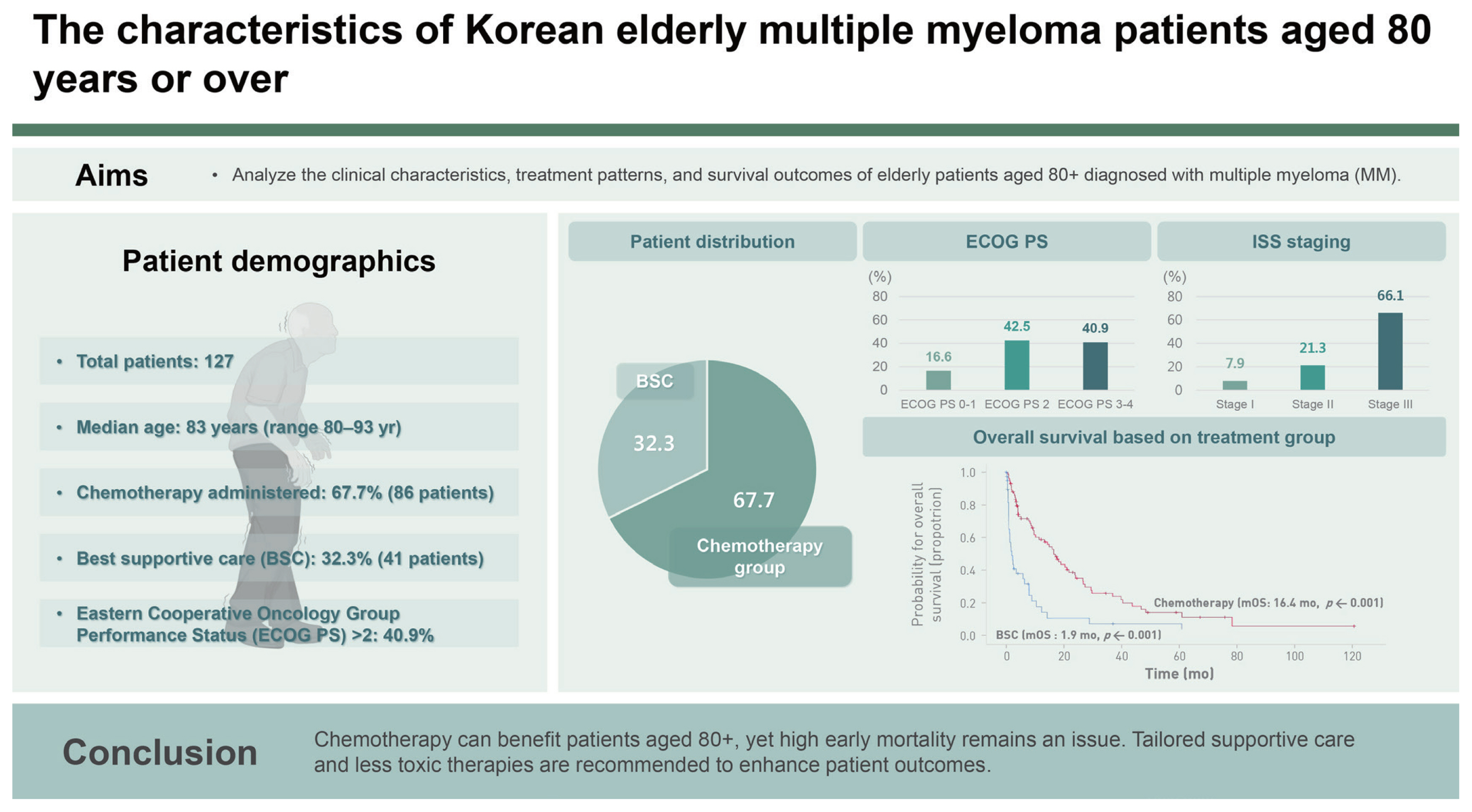

A total of 127 patients with a median age of 83 years (range, 80–93 yr) were enrolled: 52 (40.9%) with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) > 2, 84 (66.1%) with International Staging System (ISS) stage III disease, and 93 (73.2%) with a Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) > 4. Chemotherapy was administered to 86 patients (67.7%). The median overall survival was 9.3 months. Overall survival was significantly associated with ECOG PS > 2 (HR 2.26, 95% CI 1.43–3.59), ISS stage III (HR 1.99, 95% CI 1.18–3.34), and chemotherapy (HR 0.34, 95% CI 0.21–0.55). There was no statistically significant difference in event-free survival according to the type of anti-myeloma chemotherapy administered. The early mortality (EM) rate was 28.3%.

Conclusions

Even in patients with MM aged 80 years or over, chemotherapy can result in better survival outcomes than supportive care. Patients aged ≥ 80 years should not be excluded from chemotherapy based on age alone. However, reducing EM in elderly patients with newly diagnosed MM remains challenging.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematological disease characterized by the abnormal proliferation of clonal plasma cells. MM is a disease that affects older adults. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data from 1975 to 2016 showed that 36% of patients with MM were ≥ 80 years of age [1]. According to data from the United Kingdom in 2016, 45% of new diagnoses were recorded in people aged ≥ 75 years [2]. In the annual cancer statistics report of the Korea Central Cancer Registry, the proportion of patients with newly diagnosed MM aged ≥ 80 years increased from 8.5% in 2010 to 13.5% in 2019 [3]. Changes in population demographics have resulted in the increased proportion of newly diagnosed MM cases in this age group. Although patients with advanced age, especially ≥ 80 years old, account for a considerable proportion of MM cases in real-world practice, most of them are excluded from clinical trials because of poor performance status (PS), multiple comorbidities, and socioeconomic reasons [1,4–7]. Therefore, limited information is available on the clinical characteristics and survival outcomes in this group.

The SEER database from 2007 to 2013 in the United States showed that patients over 80 years of age who received chemotherapy had a higher survival rate than those who did not [1]. However, some studies have shown that early mortality (EM) in elderly patients is higher than that in other age groups because elderly patients have poor PS or comorbidities and are more susceptible to the adverse effects of chemotherapy [8–11]. The relative benefit of treatment in patients with newly diagnosed MM aged ≥ 80 years is still unclear. In addition, it is unclear whether immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors as anti-myeloma treatments benefit elderly patients with newly diagnosed MM in daily practice.

To address this issue, we analyzed the clinical characteristics and survival outcomes of patients with symptomatic newly diagnosed MM who were ≥ 80 years of age from all tertiary hospitals in Daegu, Korea. We also evaluated the clinical variables associated with survival outcomes and whether anti-myeloma treatment benefited very elderly patients.

METHODS

Patients

We conducted a retrospective analysis of medical records of Korean patients aged ≥ 80 years with newly diagnosed MM between 2010 and 2019 at five academic hospitals in Daegu, Korea.

Patients with MM who met the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) diagnostic criteria for MM were included [12], whereas patients with other plasma cell disorders such as smoldering MM, MGUS, solitary plasmacytoma, and AL amyloidosis were excluded. The following clinical and laboratory variables of patients were collected by reviewing medical records: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [13], International Staging System (ISS) [14], revised ISS (R-ISS) [15], hemoglobin, platelet count, serum calcium, serum creatinine, serum β2-microglobulin, serum albumin, serum lactate dehydrogenase, serum/urine heavy chain, light chain, presence of bone disease, high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, bone marrow examination results, systemic chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. High-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, including translocation (4:14), translocation (14:16), and deletion of 17p were identified using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) [15]. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the diagnosis of MM to death. Event-free survival (EFS) was defined as the time from the diagnosis of MM to discontinuation of treatment for any reason, including progressive disease or death [16]. Treatment response was assessed using the IMWG criteria [17]. The overall response rate (ORR) was defined as the percentage of patients who achieved a PR or a better response to treatment. EM was defined as death within the first 2 months after diagnosis [18].

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the patients are presented as medians (ranges), frequencies, or percentages and were compared using the Mann–Whitney test, Kruskal–Wallis test, or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. For survival analysis, Kaplan–Meier plots were drawn and analyzed using the log-rank test. Cox’s proportional hazard analysis was used to perform univariate and multivariate analyses of the factors associated with OS. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the risk factors for ORR for first-line chemotherapy and EM. All statistical analyses for this study were conducted using SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and a p value < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Daegu Joint Institutional Review Board (IRB No. DGIRB 2023-11-002-002) and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Because this was a retrospective study, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

This study included 127 patients with a median age of 83 years. The median duration of follow-up was 39.7 months. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Among them, 52 (40.9%) had ECOG PS scores of 3 or 4. Most patients were in ISS stage II (21.3%) or III (66.1%), and based on the R-ISS stage, most patients were in stage II (35.4%) or III (37.0%). A significant proportion of patients (93 [73.2%]) had a CCI > 4. The predominant types of MM were immunoglobulin G (IgG) (62.2%) in the heavy chain and kappa (55.9%) in the light chain. Among the CRAB symptoms (hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, and bone lesions) of MM, anemia (hemoglobin level < 10 g/dL) was the most common (74.8%), followed by bone disease (66.9%), renal failure (creatinine level > 2 mg/dL) (25.4%), and hypercalcemia (calcium level > 11 mg/dL) (8.7%). Although high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities had not been evaluated in all patients, of the 94 patients (74.0%) tested using FISH, 21 (22.3%) had high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities. Chemotherapy was administered to 86 patients (67.7%), whereas the remaining 41 patients (32.3%) received the best supportive care (BSC) (Table 1). Radiotherapy was administered to 17 patients (13.4%) with bone lesions.

Survival outcomes and prognostic factors

The median OS of all patients was 9.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 5.4–13.9). The median OS was 16.4 months (95% CI 12.1–20.8) in the chemotherapy group compared with 1.9 months (95% CI 0.6–3.2) in the BSC group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1A). The median OS was 18.9 months (95% CI 10.9–27.0) in the ECOG PS 0–2 group and 3.5 months (95% CI 0.5–6.5) in the ECOG PS 3–4 group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). Univariate and multivariate analyses of OS were performed on the clinical and laboratory variables. The median patient age was 83 years, and the age group was divided as this median patient age. In univariate analysis, several significant prognostic factors for OS were identified, including age (80–83 yr vs. ≥ 84 yr, p = 0.017), ECOG PS (0–2 vs. 3–4, p < 0.001), ISS stage (I, II vs. III, p = 0.005), treatment type (chemotherapy vs. BSC, p < 0.001), hypercalcemia (p = 0.007), and thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100 × 109/L, p = 0.007) (Supplementary Table 1). In the subsequent multivariate analysis based on the significant prognostic variables identified in univariate analysis, OS was found to be affected by ECOG PS > 2 (hazard ratio [HR] 2.26, 95% CI 1.43–3.59), ISS stage III (HR 1.99, 95% CI 1.18–3.34), and receipt of chemotherapy (HR 0.34, 95% CI 0.21–0.55) (Table 2).

Overall survival and EFS in the group of patients. (A) Overall survival in the group of patients with chemotherapy (red line) and best supportive care (blue line). (B) Overall survival in the group of patients with ECOG PS 0–2 (blue line) and 3–4 (red line). (C) EFS in the group of patients with first-line chemotherapy, bortezomib-based (blue line), lenalidomide-based (red line), and alkylating agent-based (green line). EFS, event-free survival; mOS, median overall survival; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status.

Chemotherapy for MM

The patients were divided into three groups according to the first-line chemotherapy regimen: bortezomib-based, lenalidomide-based, or alkylating agent-based regimen, including melphalan/prednisone and cyclophosphamide/prednisone. Patient characteristics in each group are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Twenty-seven patients (31.4%) were treated with bortezomib-based chemotherapy, 17 (19.8%) with lenalidomide-based chemotherapy, and 42 (48.8%) with alkylating agent-based chemotherapy. In the bortezomib-based group, the median age was 82 years, and the proportion of patients with an ECOG PS > 2 was 25.9%. The proportion of patients with CCI > 4 was 74.1%. The proportion of patients with ISS III, R-ISS III, and high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities was 70.4%, 40.7%, and 24.0%, respectively. In the lenalidomide-based group, the median age was 84 years, and the proportion of patients with ECOG PS > 2, CCI > 4, ISS III, R-ISS III, and high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities was 41.2%, 88.2%, 76.5%, 47.1%, and 53.3%, respectively. In the alkylating agent-based group, the median age was 82 years, and the proportion of patients with an ECOG PS > 2, CCI > 4, ISS III, R-ISS III, and high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities was 33.4%, 57.1%, 61.9%, 45.2%, and 11.8%, respectively. The median number of chemotherapy cycles was 3 in the bortezomib-based group (range 1–9), 3 in the lenalidomide-based group (range 1–20), and 3.5 in the alkylating agent-based group (range 1–54).

The ORR for first-line chemotherapy was 51.9%, 58.8%, and 33.3% for the bortezomib-, lenalidomide-, and alkylating agent-based groups, respectively. Univariate analyses identified bone disease (p = 0.033) and high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (p = 0.036) as parameters affecting ORR. No statistically significant factors were identified in the subsequent multivariate analysis (Supplementary Table 3).

The EFS for first-line chemotherapy was 13.4 months (95% CI 7.0–19.8) in the bortezomib group, 8.5 months (95% CI 7.8–9.1) in the lenalidomide group, and 9.6 months (95% CI 3.1–16.1) in the alkylating agent group (Fig. 1C). The EFS did not differ significantly between the first-line chemotherapy groups (p = 0.428).

EM

EM occurred in 36 of the 127 patients (28.3%). Supplementary Table 4 shows the characteristics of the patients who died within 2 months after the diagnosis of MM. Baseline factors associated with higher odds of EM included poor ECOG PS, hypercalcemia, renal failure, and not receiving chemotherapy. In multivariate analysis, only not receiving chemotherapy was an independent predictor of EM (p < 0.001), and the odds ratio for EM related to the first-line chemotherapy regimen was not significantly different (Supplementary Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Elderly patients with MM have more complex factors than chronological age, including comorbidities, disability, and frailty. In addition, the potential toxicity or side effects of chemotherapy may result in worse outcomes such as early death [1,2,4–11,19,20]. Many researchers are currently developing tools to select optimal elderly patients for treatment, reduce treatment toxicities and adverse effects, and improve survival rates [1,5–8,19,21–28].

Staging using ISS or R-ISS is the most important prognostic factor in patients with MM and has been validated in patients treated with both conventional and novel agents; however, the median age of patients in the analysis of ISS was 60 years [14], and the median age of patients in the analysis of R-ISS was 62 years [15]. Therefore, it is necessary to re-evaluate the validity of the ISS and R-ISS as prognostic factors in patients aged ≥ 80 years. Some studies have reported that the ISS retains its value in assessing patient prognosis in all age groups [6,22,25]. Several studies have shown that elderly patients with MM tend to have a more advanced ISS stage and that a higher ISS stage was a risk factor for poor prognosis and EM in this population [5,6,8,22,23]. In this study, ISS stage III was a significant factor associated with poor OS of patients ≥ 80 years of age.

Several retrospective studies have shown that disease-related factors such as stage and chromosomal findings are predictive of survival outcomes, and patient-related factors such as PS and comorbidity burden are important predictors of survival in elderly patients [5–7]. Our study identified ECOG PS as a significant factor associated with OS. However, we could not determine the relationship between CCI and survival.

Elderly patients who receive anti-myeloma chemotherapy have superior survival rates than those who do not receive chemotherapy [1]. In our study, chemotherapy was also identified as a statistically significant factor in multivariate analysis for OS. However, survival outcomes did not differ significantly among the groups divided by chemotherapy regimen. Generally, the lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) regimen is well tolerated in clinical practice and is recognized for its improved efficacy [29]. In this study, more patients had ECOG PS > 2, CCI > 4, ISS III, R-ISS III, or high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities and were older in the lenalidomide-based group. These patient characteristics may explain why the lenalidomide-based group did not show better outcomes than the other groups. In this study, nearly half of the patients received alkylating agent-based chemotherapy, but the proportion of this group decreased over time, and the proportion of both the bortezomib- and lenalidomide-based groups rapidly increased. This trend is likely related to the time of approval for each chemotherapy regimen. In Korea, combination chemotherapy with bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisolone (VMP) was approved as a first-line anti-myeloma therapy in 2011, and Rd were approved as a first-line therapy in 2017. There was no significant improvement in median OS related to the time of Rd or VMP approval.

The EM rate for all patients in our study was 28.3%, which was higher than that reported in other studies [18,22]. The reasons for the high rate of EM in our study were that many patients had a poor ECOG PS and were older. In other EM-related studies, the strongest predictors of EM were ECOG PS, older age, ISS stage, light-chain disease, and baseline renal impairment [8,10,11,18,22].

Our study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study with a small number of patients. Consequently, some clinical and laboratory data were missing, such as the cause of treatment discontinuation and cytogenetic findings. Second, there was no geriatric assessment of patients in this study. A prospective multicenter cohort study showed that geriatric assessment is a prognostic factor for predicting treatment-related toxicity and survival in older patients with other hematologic malignancies [30]. If elderly patients with MM are selected for anti-myeloma chemotherapy through geriatric assessment, the OS and EM rates may be improved. However, despite these limitations, our study reflects the real-world population of elderly patients with MM aged 80 years or over, and the results of this study may be useful for the management of elderly patients with MM.

In conclusion, chemotherapy can lead to better survival outcomes than BSC, even in elderly patients with MM aged 80 years or over. ISS and ECOG PS may be considered significant prognostic factors in elderly patients with MM. However, the EM rate was higher in elderly patients with newly diagnosed MM. Tailored supportive care and more effective and less toxic anti-myeloma treatments are needed to reduce the EM rate.

KEY MESSAGE

1. Chemotherapy can result in better survival outcomes than BSC, even in elderly patients with MM aged 80 years or over.

2. ISS and ECOG PS were identified as significant prognostic factors for elderly patients with MM.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Sang Hwan Lee: methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, visualization; Hee-Jeong Cho: methodology, data curation; Joon Ho Moon: methodology, data curation; Ji Yoon Jung: methodology, data curation; Min Kyoung Kim: methodology, data curation; Mi Hwa Heo: methodology, data curation; Young Rok Do: methodology, data curation; Yunhwi Hwang: formal analysis, writing - review& editing; Sung Hwa Bae: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing - review & editing

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

None