Current status of modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease in Korean women

Article information

Abstract

Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, and smoking are the primary modifiable risk factors contributing to the increasing morbidity and mortality rates from cardiovascular disease (CVD) among Korean women. Significant sex-related differences exist in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of these risk factors, highlighting the importance of age- and sex-specific approaches to the management and prevention of CVD. Notably, the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus increases with age, with a higher prevalence in elderly women compared to men. Dyslipidemia and obesity are also trending upward, particularly in postmenopausal women, highlighting the impact of menopause on cardiovascular risk. The present review advocates for improved diagnostic, therapeutic, and educational efforts to mitigate the risk of CVD among Korean women, with the goals of reducing the overall burden of the disease and promoting better cardiovascular health outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

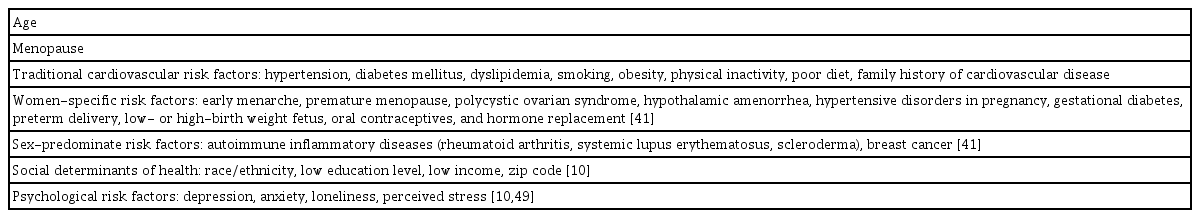

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the second leading cause of death among both men and women according to the 2020 report of death statistics in Korea [1]. Interestingly, the mortality rate due to cardiovascular and cerebral diseases was 1.1 times higher in women than in men and increased rapidly with age, particularly from the 70–79 age group onward [1]. Specialized investigations into the risk of CVD in women have enhanced our understanding of not only traditional risk factors but also sex-specific risk factors, social determinants, and psychological factors, all of which are crucial for the detection of CVD and the reduction of mortality (Table 1) [2].

During the past few decades, Korea has experienced rapid economic and social transformations, resulting in significant shifts in lifestyle and dietary patterns [3]. Clarifying the modifiable risk factors specific to Korean women is critical for addressing the public health challenge of the CVD burden in this population. Women may experience CVD symptoms, risk factors, and outcomes different from those in men. Investigating these factors within the cultural and social context of Korean women can lead to more tailored prevention and treatment strategies. The traditional Korean diet, renowned for its rich content of vegetables and fermented foods, is evolving toward an increased preference for a Western-style diet high in saturated fats and sugars, particularly among younger generations and in urban settings [4]. This shift in dietary habits has implications for CVD risk factors, including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. By identifying the most significant modifiable risk factors for CVD among Korean women, public health strategies can be more effectively formulated to address these concerns. Tailored educational campaigns and prevention programs can be developed to meet the unique needs and challenges of this demographic.

In this article, we review the current status of modifiable risk factors for CVD in Korean women in an effort to develop targeted, effective public health strategies that address the unique needs of this population, contributing to the reduction of CVD morbidity and mortality.

HYPERTENSION

Differences in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates of hypertension between men and women have led to significant public health challenges worldwide, including in Korea. The average blood pressure among Korean adults decreased from 1998 to 2008, but has changed minimally in recent years [5]. Moreover, the aging population continues to contribute to a steady increase in the incidence of hypertension. Notably, hypertension has been recognized as a more potent risk factor for CVD in Asian women than men. According to the Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration, hypertension accounts for 8% to 39% of ischemic heart disease cases among women, compared to 4% to 28% among men [6].

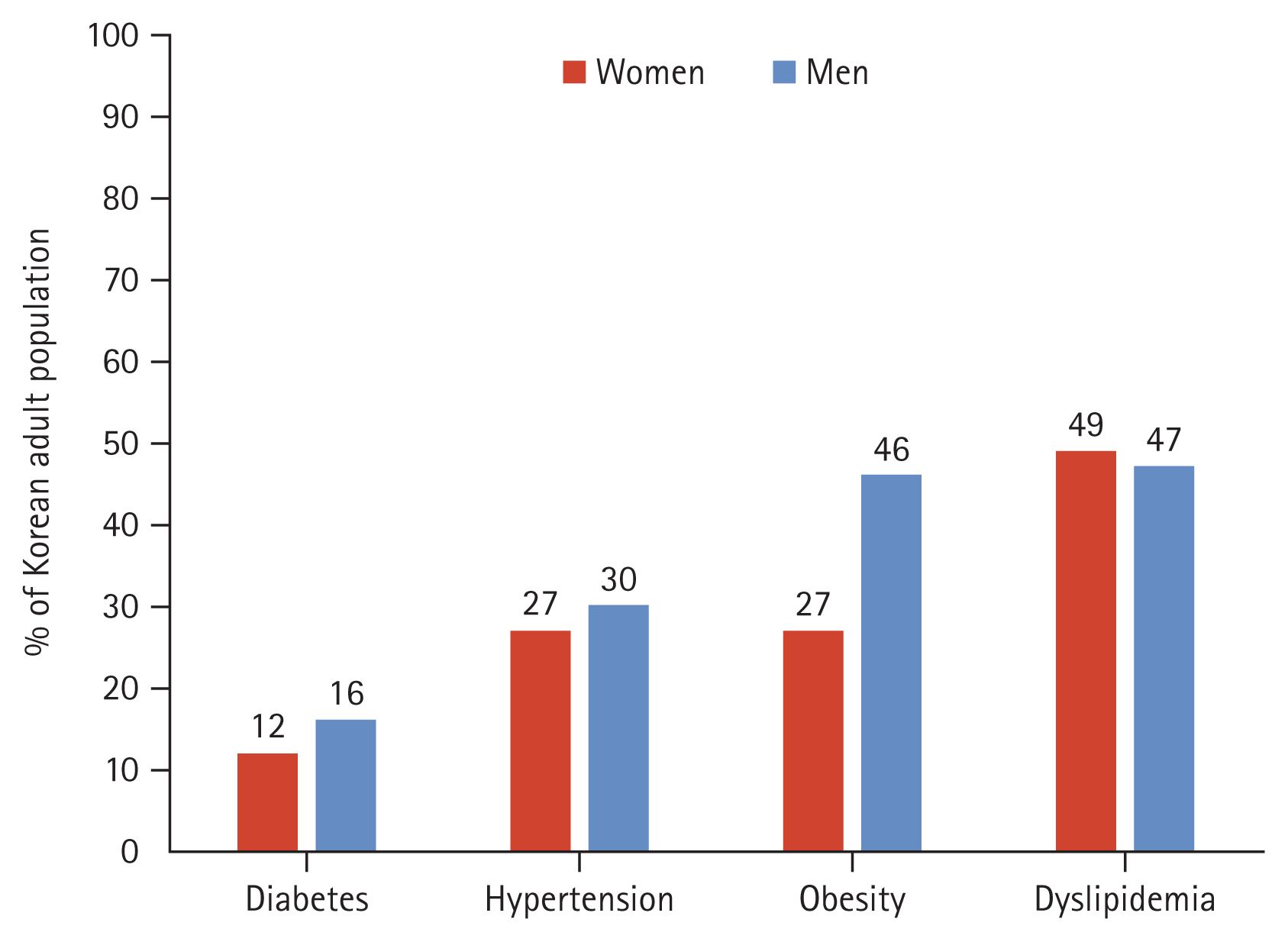

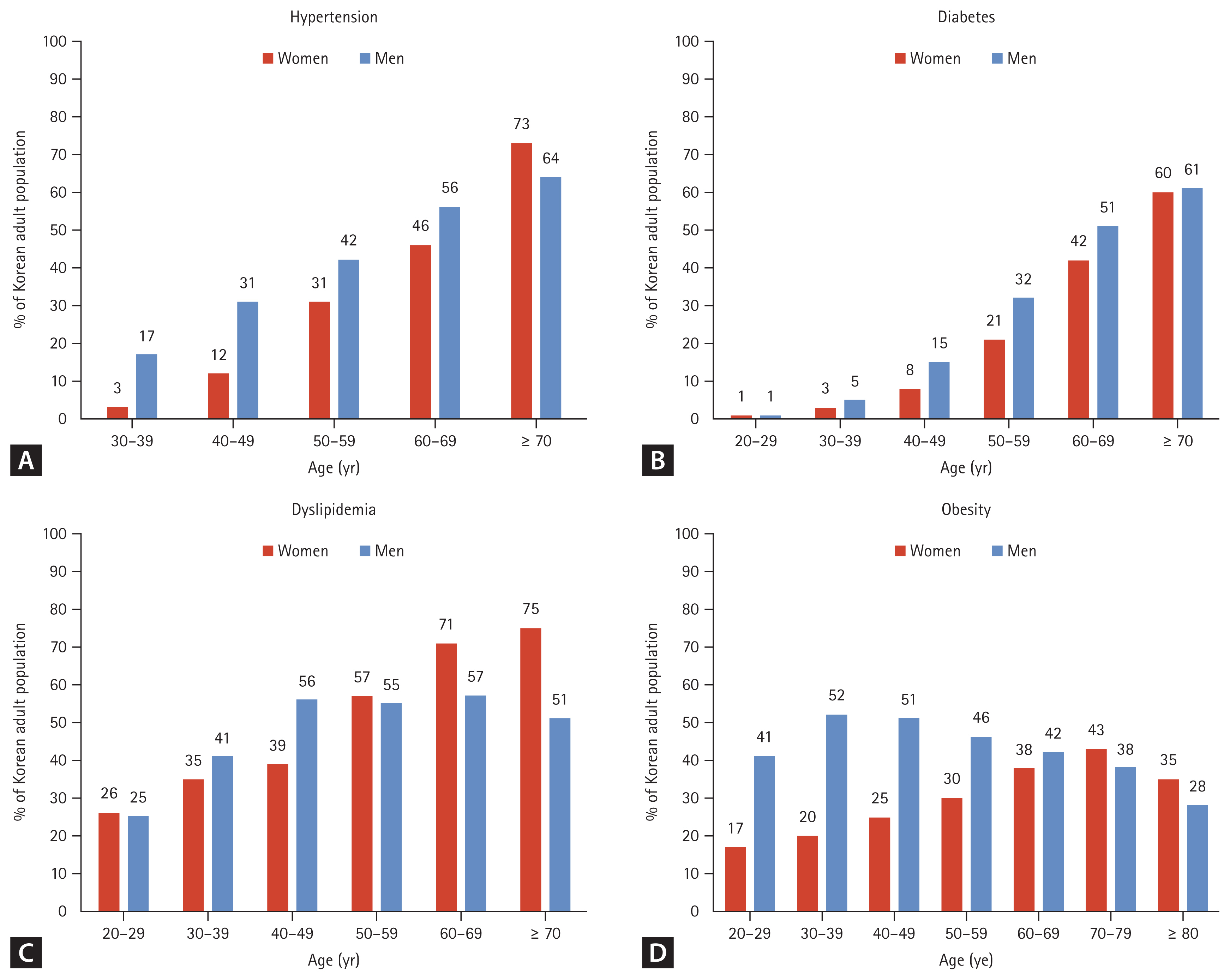

According to the Korea Hypertension Fact Sheet 2021, the prevalence of hypertension in 2019 among individuals aged ≥ 20 years was 30% in men and 27% in women (Fig. 1) [7]. In 2019, the number of Korean people with hypertension exceeded 12 million. The estimated number of people with hypertension was 4.34 million men and 2.78 million women under the age of 65, and 1.96 million men and 2.99 million women aged 65 and older, indicating that hypertension is more prevalent and increases more rapidly in elderly women [7]. Figure 2A presents the prevalence of hypertension in women and men by age among Korean adults in 2016 [8]. The prevalence of hypertension differs by sex: it is higher in men than in women until the sixth decade of life, after which the trend reverses, and the prevalence becomes higher in women in their 70s [8]. Furthermore, recent findings suggest a decrease in the effectiveness of hypertension management among elderly Korean women. Notably, women have higher hypertension control rates than men until the age of 60 years; however, beyond this age threshold, control rates reverse, diminishing and becoming lower in women than in men [7]. Consequently, it is imperative to focus on enhancing the diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes of hypertension in elderly women.

Prevalence rate of selected cardiovascular risk factors for Korean women and men by age. (A) Hypertension. (B) Diabetes mellitus. (C) Dyslipidemia. (D) Obesity. Hypertension data were obtained from Kim et al. [8], diabetes mellitus data were obtained from Oh et al. [15], dyslipidemia data were obtained from Jin et al. [18], and obesity data were obtained from Yang et al. [25].

Although the prevalence of hypertension may not be high among women in their 20s and 30s, this young demographic warrants particular attention because of considerations related to pregnancy. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers are prescribed less frequently to young women than men. Nevertheless, in 2019, 61% of Korean women aged 20 to 39 years with hypertension were prescribed angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers [5]. Renin–angiotensin system blockers should be avoided during pregnancy because they can interfere with fetal kidney development and function [9], and patient education is therefore necessary when prescribing renin–angiotensin system blockers to young women. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of developing postpartum hypertension and an overall heightened risk of CVD [10]. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, especially gestational hypertension, have been rapidly increasing in Korea during the past decade. Preeclampsia and eclampsia were decreasing until 2014 but have seen a resurgence in recent years [7]. As the trend of older pregnancies continues among women in Korea, there is a growing need for more attention to hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, particularly among young Korean women.

DIABETES MELLITUS

The global prevalence of diabetes is increasing and is correlated with the nearly universal escalation in body mass index (BMI) attributable to unhealthy dietary habits, sedentary lifestyles, and increasing urbanization [11]. Typically, men are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus at an earlier age and with a lower BMI compared with women. Upon diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, women frequently exhibit a greater burden of risk factors than men, characterized by elevated blood pressure and more significant excess weight gain [12]. Furthermore, the likelihood of developing incident coronary heart disease is 44% higher in women than men with diabetes under the same clinical conditions [13].

According to the Diabetes Fact Sheet in Korea 2021, the estimated prevalence of diabetes mellitus among adults aged ≥ 19 years was 13.9% in 2020, with a sex distribution of 15.8% among men and 12.1% among women (Fig. 1) [14]. The prevalence among adults aged ≥ 65 years increased to 30.1%, with a sex distribution of 29.8% among men and 30.2% among women [14]. In Korea, the prevalence of diabetes rose from 10.3% in 2011 to 13.9% in 2020, although about one-third of individuals aged ≥ 30 years with diabetes are estimated to have been undiagnosed during this time [14]. Furthermore, awareness of diabetes has declined, dropping from 72.4% between 2007 and 2009 to 67.8% between 2016 and 2018 [14].

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus progressively increases with advancing age. Figure 2B presents the prevalence of diabetes mellitus among Korean women and men by age in 2017 [15]. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was consistently higher in men than women across all age groups, exhibiting a gradual increase with age. However, the rate of increase in the prevalence of diabetes among women accelerated with age at a faster pace than among men, leading to a convergence in the prevalence rates of the condition for both sexes by the time individuals reached their 70s [15].

Between 2019 and 2020, 65.8% of adults diagnosed with diabetes mellitus were both aware of their condition and received treatment with antidiabetic medications [14]. Nevertheless, only 24.5% of these individuals achieved the glycemic control target of an HbA1c level of < 6.5%, a figure that remained consistent across both sexes despite the increased use of new antidiabetic drugs [14]. A concerning trend was the deterioration of risk factor management among adults with diabetes mellitus. While hypertension and blood pressure management remained relatively stable, lipid control declined and the prevalence of obesity among individuals with diabetes mellitus increased [14].

DYSLIPIDEMIA

Dyslipidemia is a major risk factor for CVD. One study identified comparable cardiovascular risk in association with heightened cholesterol levels in women relative to men [16]. Menopause is associated with the development of a more atherogenic lipid profile, significantly contributing to the elevated risk of CVD in postmenopausal women [17]. In Korean women, menopause is reached at a mean age of 49.3 years [2], around which time there is a significant fluctuation in serum lipid concentrations.

The incidence of hyperlipidemia or dyslipidemia has been trending upward in Korea. Notably, the prevalence of hypercholesterolemia has undergone consistent increases. The age-standardized prevalence of hypercholesterolemia was 19.9% in 2020, doubling from 8.8% in 2007. The crude prevalence of hypercholesterolemia was 24.0% in 2020 [18].

The criteria for defining hypo–high-density lipoprotein cholesterolemia (HDL-C) vary by sex [19]. Consequently, when the threshold for hypo-HDL-C is uniformly set at < 40 mg/dL for both men and women, the prevalence of dyslipidemia in women can be underestimated. Therefore, the Korea Dyslipidemia Fact Sheet 2022 further delineated the prevalence of dyslipidemia based on the hypo-HDL-C criterion of an HDL-cholesterol level of < 40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women [18]. Following the application of this definition, the reported prevalence of dyslipidemia was comparable between the two sexes in 2020 (47.4% in men and 49.0% in women) (Fig. 1) [18]. In the age group of 30 to 49 years, men had a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia, but this sex-related disparity began to reverse in individuals in their 50s, with prevalence rates of 55% in men and 57% in women [18]. Among men, the frequency of dyslipidemia remained relatively stable, ranging from 56% in their 40s to 57% in their 60s before decreasing to 51% in their 70s. Conversely, the prevalence in women showed a continuous upward trend with advancing age, peaking at 75% in their 70s (Fig. 2C) [18].

Despite consistent increases in the prevalence of hypercholesterolemia and dyslipidemia in Korea, treatment rates continues to be low. Awareness, treatment, and control rates for hypercholesterolemia from 2019 to 2020 were 63.0%, 55.2%, and 47.7%, respectively [18]. Since 2007, the crude prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates for certain conditions have been marginally higher in women than in men. However, the disparity in control rates has diminished over time, and as of 2020, the control rates were nearly identical between the two sexes [18].

Notably, there is a concerning deterioration in dyslipidemia trends among Korean youth of both sexes. This is evidenced by a study focusing on individuals aged 10 to 18 years, using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. This negative trend is likely attributed to an increase in central obesity in Korean adolescents, which has been a topic of concern [20].

OBESITY

The prevalence of obesity is higher among women than men in most countries [21]. However, obesity rates are influenced by the interplay of various factors, including sociocultural, environmental, and physiological differences, and complex interactions take place among weight status, sex, and socio-environmental determinants [21]. Globally, a BMI of > 25 kg/m2 is classified as overweight, while a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 is considered obese [22]. For the Korean population, obesity is defined as a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 in alignment with the guidelines set forth by the Asia-Pacific Region and the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity [23,24].

According to the Korea Obesity Fact Sheet 2021, the prevalence of obesity among Koreans in 2019 was 46.2% among men and 27.3% among women (Fig. 1) [25]. This marked a significant divergence from patterns observed in countries such as the United States, where the prevalence of obesity is higher among women than men [26]. The prevalence of abdominal obesity stands at 29.3% in men and 19.0% in women, indicating a relatively lower occurrence of abdominal obesity among Korean women [25].

This review also revealed a sharp increase in both general and abdominal obesity in men during the transition from their 20s to 30s, but the prevalence of obesity in men aged ≥ 70 years was comparatively lower [25]. In contrast, the prevalence of obesity was significantly higher among elderly women in their 60s and 70s than in younger women in their 20s and 30s (Fig. 2D) [25]. The prevalence of abdominal obesity among elderly Korean women, specifically those in their 60s and 70s, has significantly risen: it was 3.4 times higher in women in their 60s than in women in their 20s (29.0% vs. 8.6%), highlighting a rapid escalation of abdominal obesity, alongside obesity defined by BMI, with advancing age [25].

A primary concern is the escalating trend of obesity nationwide. During the past 11 years, there has been a marked increase in the prevalence of both general and abdominal obesity among the entire population of Korea [25]. In particular, the rate of increase in obesity has surged among individuals in their 20s and 80s in contrast to other age groups [25]. Within the framework of an aging population, Korean women in particular are exhibiting a continuous increase in obesity rates, underscoring the imperative for targeted strategies in the diagnosis and management of obesity.

SMOKING

Cigarette smoking is recognized as the primary contributor to CVD and various other non-communicable diseases [27]. In most countries, the prevalence of smoking is lower among women than among men [28]. On a global scale, the estimated prevalence of adult smoking in 2020 was 32.6% in men and 6.5% in women [29].

The prevalence of cigarette smoking in Korea, predominantly among men, has undergone consistent declines in recent years [29]. The smoking rate among Korean men was notably high in 1980, reaching 79%, but thereafter decreased and fell to < 40% after 2015 [30]. According to a survey conducted in 2021, approximately 33% of men were smokers, compared with only 5.5% of women [29].

Despite the notably lower smoking rates among Korean women than men, there are important factors to consider. Park et al. [28] noted a significant disparity in smoking rates among women. The self-reported rate was 7.1%, whereas urine nicotine concentration measurements indicated a rate of 18.2%. For men, these rates were 47.8% and 55.1%, respectively. This considerable discrepancy in self-reported rates among women implies a high incidence of inaccurate reporting, leading to underestimates of the smoking prevalence among Korean women [28]. Moreover, studies have indicated that the prevalence of smoking among Korean women has consistently increased across recent birth cohorts; this is in contrast to Korean men, for whom the smoking prevalence peaked among those born between 1959 and 1963 and subsequently declined [31]. Consequently, there is a pressing need for policy interventions specifically aimed at young female smokers, emphasizing a proactive approach that addresses the underlying causes of smoking among women.

PHYSICAL INACTIVITY

Extensive research has established a correlation between sedentary behavior and an elevated risk of CVD, with evidence suggesting that women tend to be more sedentary than men [32]. The World Health Organization’s physical activity guidelines recommend at least 150 minutes per week of moderate activity or 75 minutes per week of vigorous activity [33]. However, an analysis of the 2017 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey revealed that 66% of Koreans failed to meet these criteria [34]. Moreover, Korean women had a higher prevalence of physical inactivity than men (74.0% vs. 57.9%, respectively), with women aged > 65 years demonstrating the lowest frequency of moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity and resistance exercise [34].

A prospective study of adults in the United States revealed that compared with men, women experienced more significant reductions in both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risks with comparable levels of leisure-time physical activity [35]. These findings could bolster initiatives aimed at narrowing the sex-related disparity in physical health by particularly encouraging elderly Korean women to participate in regular physical activity.

DIET AND ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION

Emerging evidence indicates that adhering to a nutritious dietary regimen can mitigate risk factors associated with CVD in adults [36]. Consequently, officials have encouraged decreased consumption of saturated and trans-fatty acids; increased intake of unsaturated fatty acids, complex carbohydrates, and dietary fiber; and low sodium intake [37].

According to the findings from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2007 to 2018, the age-standardized mean score of the Korean Healthy Eating Index slightly increased during this time span for both men and women, indicating modest enhancements in overall quality of diet. This trend was similar for both sexes, but women consistently had a higher quality of diet [3]. However, variations in quality of diet were observed across different age groups and birth cohorts, with younger adults and more recent birth cohorts displaying poorer dietary habits, affecting both men and women [3].

Excessive alcohol consumption is widely recognized as a significant factor contributing to mortality and the overall burden of CVD [38]. Research has confirmed that the daily intake of pure alcohol among Korean adults, both men and women, has been rising [39]. Men consumed substantially more alcohol than women from 2016 to 2018 (23.94 vs. 5.79 g/day, respectively), but rates of increases in consumption were higher among women [39]. Specifically, men aged 30 to 49 years and women aged 19 to 29 years have been identified as consuming the most alcohol, exhibiting the most significant upward trend in consumption [39]. The increasing trends of alcohol consumption among young Korean women are becoming an issue of concern.

UNSOLVED PROBLEMS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

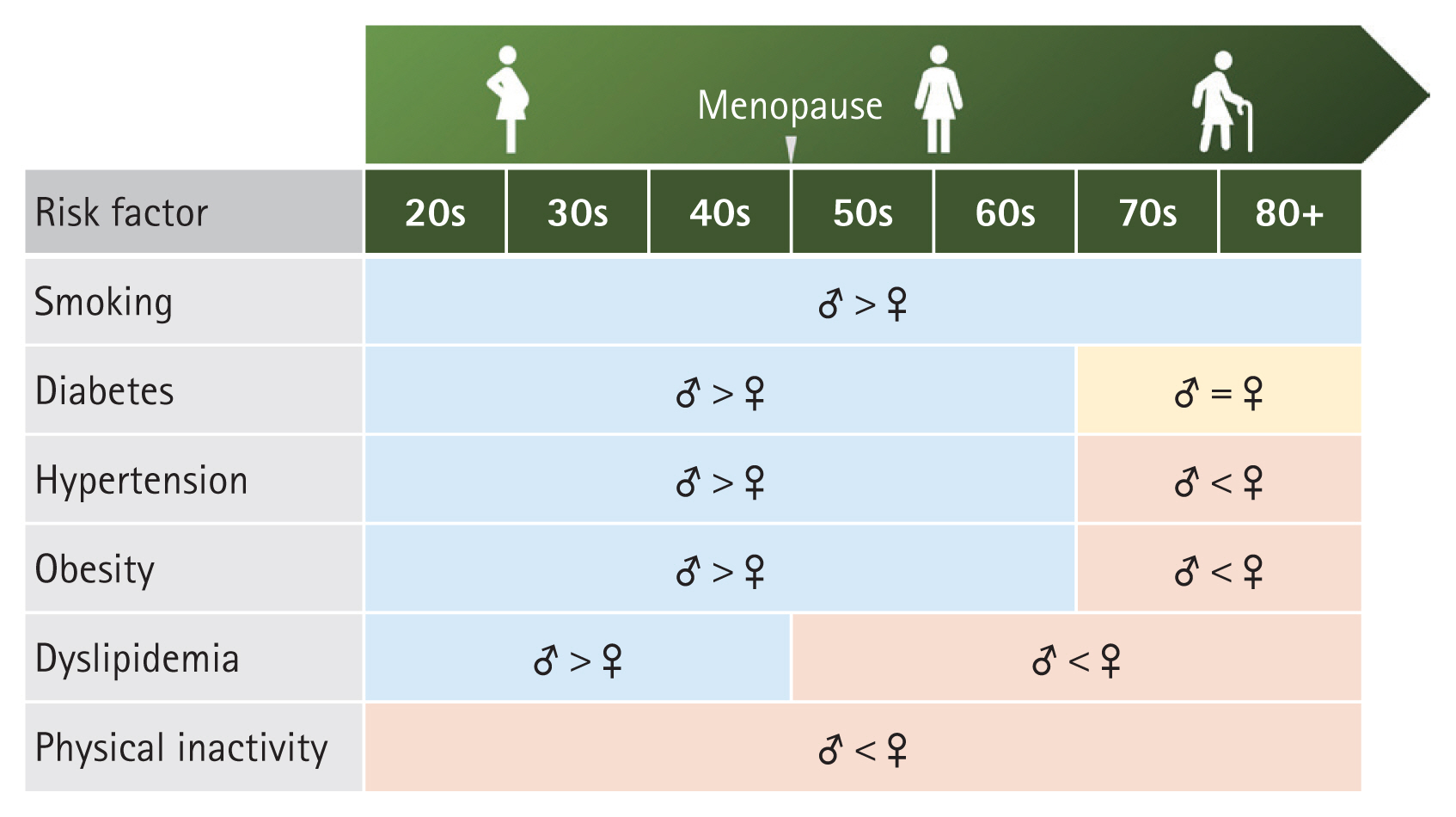

With the growth of the elderly population, there has been a corresponding rise in risk factors, potentially leading to an increase in CVD. This is particularly concerning for women, who typically live longer and thus experience an increase in CVD risk factors as they age, highlighting the need for appropriate interventions. Figure 3 presents the prevalence rates of CVD risk factors across the lifespan of Korean women, showing that most risk factors are reversed between men and women after the age of 70 years. The prevalence of individuals presenting with two or more of the five CVD risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking) significantly increases with age according to the Korea Heart Disease Fact Sheet 2020 [40]. This age-associated trend is evident in both sexes, with men displaying a higher incidence of these risk factors until 70 years of age and women exceeding this number at > 70 years of age [40].

Prevalence rates of modifiable cardiovascular disease risk factors across the lifespan of Korean women. ♂, men; ♀, women.

Beyond traditional risk factors, women may also be affected by unique sex-related factors such as pregnancy-related complications [41]. Psychological risk factors such as depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders are more common in Korean women than men [42,43]. Korean women had higher risks of anxiety and stress than men during the COVID-19 pandemic [44]. Thus, Korean women may be more vulnerable to psychological risk factors than Korean men, highlighting the need for attention to these underestimated risk factors. In the future, it will be essential to incorporate these diverse risk factors into CVD risk prediction, particularly for women. Considering the involvement of various sex-related risk factors and the higher burden of psychological factors, the adoption of artificial intelligence and digital tools may prove more beneficial for risk prediction in women [45].

The increasing risk factors among young Korean women are also problematic. While Korean women generally have a low prevalence of obesity, there is a rising trend in obesity overall. Specifically, smoking and alcohol consumption among young Korean women are suspected to be on the rise, highlighting the need for targeted interventions. Poor quality of diet among younger adults and more recent birth cohorts is also an issue of concern in both men and women.

Although the mortality rates from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease are comparable between women and men in Korea, women frequently perceive CVD as predominantly affecting men and thus underestimate their own risk [1]. Kim et al. [46] reported that many Korean women are underinformed about CVD and are deprived of essential information channels with which to assess public knowledge and awareness about CVD in women. The American Heart Association has launched initiatives such as the Go Red for Women campaign [47] and a call to action to address heart disease in women [26]. Similar action is required in Korea. The Women’s Heart Disease Research Working Group in Korea has been conducting research on heart disease in Korean women through projects such as the KoRean wOmen’S chest pain rEgistry (KoROSE) [48]. More deliberation is needed in terms of how best to expand awareness and research efforts for Korean women.

CONCLUSION

Sex-specific public health strategies are needed because of the increasing prevalence of hypertension and diabetes with age, the rising prevalence of dyslipidemia and obesity (especially post-menopause), and the persistent smoking rates among Korean women. Effective management and prevention efforts tailored to Korean women will be crucial for reducing CVD morbidity and mortality, taking into account the unique trends and challenges posed by these risk factors.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

In-Jeong Cho: conceptualization, investigation, writing -original draft, visualization; Mi-Seung Shin: conceptualization, writing - review & editing, supervision

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

None