Vaccination strategies for Korean patients with inflammatory bowel disease

Article information

Abstract

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are vulnerable to vaccine-preventable infectious diseases. Immunosuppressive drugs, which are often used to manage IBD, may increase this vulnerability and attenuate vaccine efficacy. Thus, healthcare providers should understand infectious diseases and schedule vaccinations for them to reduce the infection-related burden of patients with IBD. All patients with IBD should be assessed in terms of immunity to vaccine-preventable diseases at the time of IBD diagnosis, and be vaccinated appropriately. Vaccination is becoming more important because of the unprecedented coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global health crisis. This review focuses on recent updates to vaccination strategies for Korean patients with IBD.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is increasing rapidly in many Asian countries [1–3]. Because IBD is an immune-mediated chronic disease, the majority of patients require lifelong treatment with immunosuppressive agents, such as thiopurines, methotrexate, biologics, and small molecule agents [4]. In line with the treat-to-target concept now being emphasized, these immunosuppressive agents are being widely used at an early stage, and for long-term maintenance [5–9]. However, this treatment strategy carries an increased risk of opportunistic infections [10–12]. Accordingly, appropriate screening and vaccination programs are needed for patients with IBD [13–16]. However, as vaccination is not always well-conducted in clinical practice [17], many IBD patients are vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases. Vaccination has become one of the most important health maintenance strategies for IBD patients during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In this review, we discuss recent updates to vaccination strategies for patients with IBD in Korea.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT OF IMMUNE STATUS

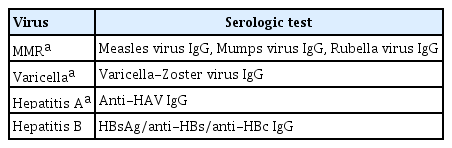

Healthcare providers should ascertain patients’ immunity to vaccine-preventable diseases at the time of IBD diagnosis [13,16,18]. Vaccination and infectious disease history data should be obtained [13,16]. Detailed records of immunizations are important, particularly for children with IBD [19]. In addition, the immune status should be regularly determined during follow-up because vaccination recommendations vary depending on age, immunosuppressive therapy, and the patient’s medical condition [13,18]. If a patient does not have vaccine-induced immunity or any history of previous infection, serologic testing can be used to check the immunity status [13,15]. Table 1 presents the serological tests used to evaluate immune status in patients with IBD. Note that vaccination history is more important than serological screening because vaccine-induced antibodies may not reflect the patient’s actual vaccine-induced immunity [16]. If there is no immunity, all appropriate vaccinations should be administered promptly [13,16].

TWO MAIN TYPES OF VACCINES

The classification of inactivated and live attenuated vaccines is presented in Table 2. Inactivated vaccines, also known as killed vaccines, use dead virus or bacterium to stimulate antibody production by triggering an immune response [20]. Inactivated vaccines are safe regardless of immunosuppression status [21]. However, it is recommended that administration be completed at least 2 weeks before initiating immunosuppressive therapy to maximize the effect of the vaccination [14]. Inactivated vaccines generally provide weaker immunity than live vaccines, so subsequent booster shots are often required [22]. Live attenuated vaccines, including measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), herpes zoster (HZ), and varicella vaccines should not be administered to patients undergoing immunosuppressive treatment due to the risk of developing the disease thereafter due to uncontrolled replication of the virus [20,21]. Live vaccines should be administered at least 4 weeks before starting immunosuppressive therapy. Patients already on immunosuppressive medications should stop at least 3 months before receiving a live vaccine [4]. Recent evidence suggests that live vaccines may be safely administered to a subset of immunocompromised patients [23]. However, further research is needed on this issue. Additionally, the administration of a live vaccine can depend on the definition of immunosuppression being used; this is described in more detail below.

DEGREE OF IMMUNOSUPPRESSION

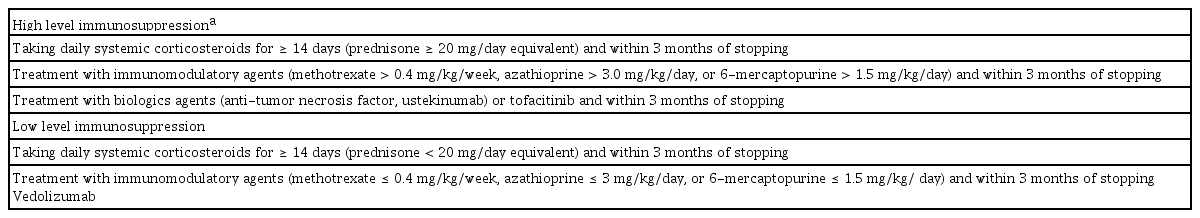

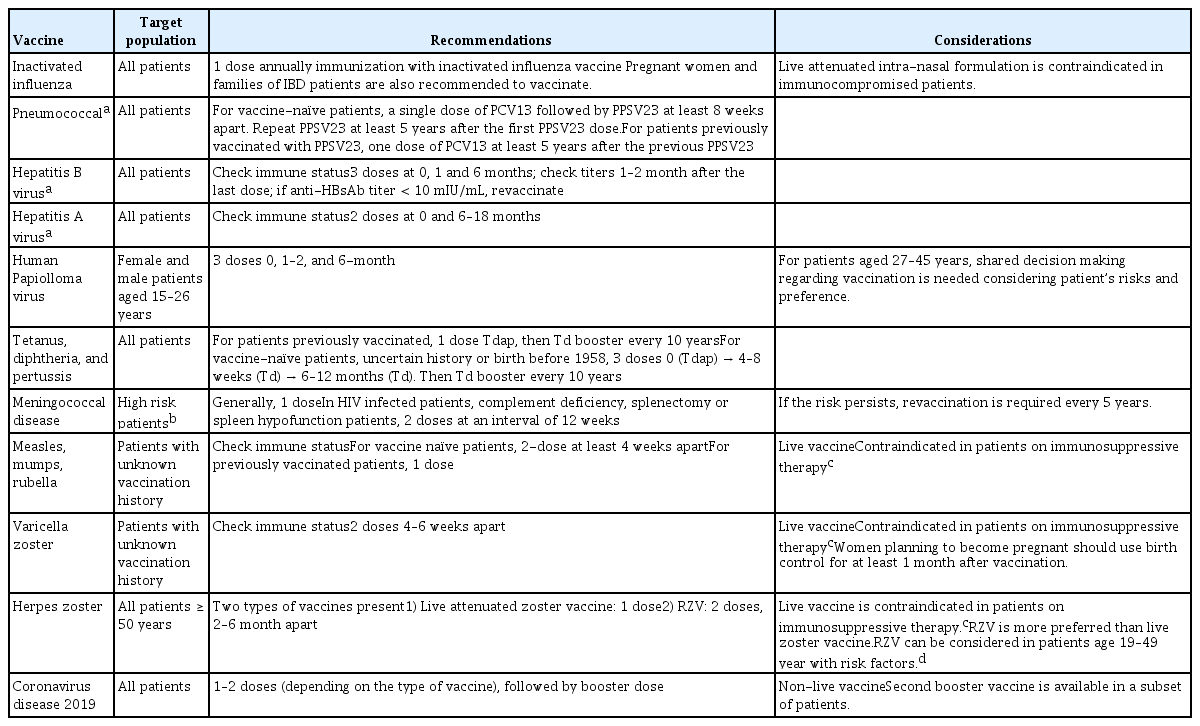

Patients with IBD should ideally be vaccinated before commencing any immunosuppressive therapy, to achieve effective immunogenicity to the vaccine. Live attenuated vaccines should not be given during immunosuppressive therapy, particularly to a patient exhibiting a high level of immunosuppression [4,13]. However, vaccination should not delay immunosuppressive therapy in patients who urgently needs treatment for IBD [4,13]. Definitions of immunosuppression are presented in Table 3 [13,21,24,25]. If a live vaccine must be administered to a highly immunosuppressed patient, the immunosuppressive therapy should be discontinued 3 months before administering the vaccine [16]. However, certain live vaccines, such as travel vaccines, may be considered if the benefits outweigh the risks in a patient with a low level of immunosuppression [16]. Hence, the degree of immunosuppression of the patient and their medical condition should be considered together to ensure appropriate timing of vaccination. A summary of the recommendations for vaccines in patients with IBD is presented in Table 4 [16,26–30].

INACTIVATED VACCINES

Influenza vaccine

Patients with IBD have an increased risk of influenza and are more likely to be hospitalized compared with the general population [31]. Many studies have reported that appropriate immunological responses can be achieved in patients with IBD after inactivated influenza vaccination, although the response can be blunted in patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy [32,33]. Antigenic drift or a mutation in surface hemagglutinin or neuraminidase proteins, which are involved in the host recognition of viral particles, often occur. Thus, seasonal influenza viruses tend to be quite different from each other and can overcome host immunity [34]. Therefore, all guidelines recommend that the influenza vaccine be administered annually [14,15,25]. The importance of influenza vaccination was emphasized during the COVID-19 pandemic given the clinical similarity between COVID-19 and influenza [15,34,35]. Caution should be exercised when using a live attenuated intranasal formulation, which is contraindicated in pregnant, critically ill, and immunocompromised patients [21]. In addition, other members’ of IBD patients’ households should receive the influenza vaccination every year [25].

Pneumococcal vaccine

Patients with IBD have an increased risk of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) [36,37]. This increased risk is observed even before IBD diagnosis or initiation of immunosuppressive therapy, implicating an underlying immunological change related to the pathogenesis of IBD in the higher risk of IPD [37]. However, 1-year mortality rates were significantly lower among pneumococcal-vaccinated than-unvaccinated IBD patients [38]. The immune response to pneumococcal vaccination in IBD patients is comparable to that of the general population, but immunosuppressive therapy may impair immunogenicity [39,40]. Guidelines recommend pneumococcal vaccination for all adult patients with IBD who are receiving or scheduled for immunosuppressive therapy [14,25]. A pneumococcal vaccine should ideally be provided at the time of IBD diagnosis, or before initiating immunosuppressive therapy, to achieve a higher level of seroprotection and greater immune response [16]. The recommended vaccination regimen is as follows: a single dose of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine followed by a single dose of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23), at least 8 weeks apart. An additional PPSV23 dose is recommended at least 5 years after the first PPSV23 dose.

Hepatitis B vaccine

South Korea is a hepatitis B virus (HBV)-endemic area; however, the prevalence of HBV has decreased substantially since a nationwide vaccination program was implemented in 1995 [41]. Although patients with IBD may be more likely to be exposed to HBV infection due to frequent invasive procedures and blood transfusions [4], IBD is no longer a risk factor for HBV infection even in HBV-endemic areas [42–45]. Interestingly, the frequency of non-immunity against HBV is high among younger IBD patients in Korea [46,47]. Furthermore, immunosuppressive therapy in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patients may reactivate HBV, which can be fatal [48,49]. Therefore, HBV immune status should be determined, particularly at IBD diagnosis, and any non-immunized patient with IBD should be vaccinated, particularly before initiating biologics or oral cytokine inhibitor treatment [24,50].

The standard regimen for vaccination against HBV in patients with IBD is the same as that for the general population: three doses at 0, 1, and 6 months [50]. However, an adequate immune response to the HBV vaccine is not achieved in a considerable number of IBD patients [51]. A recent meta-analysis including 1,688 IBD patients from 13 studies reported a response rate to HBV vaccination (defined as an hepatitis B surface antibodies [anti-HBs] titer > 10 mIU/mL) of only 61% [52]. Young age and vaccination during remission predicted an immune response, while patients prescribed immunosuppressive therapy had a lower likelihood of responding [53]. Therefore, although healthy individuals do not require routine follow-up serological tests after HBV vaccination, serological titers should be evaluated 1–3 months after the last HBV vaccination in immunocompromised patients to ensure a response [50]. Although further research is needed [14], experts recommend performing additional reactivation cycles (at 0, 2, and 6 months) if seroprotection is not achieved [15,50].

Hepatitis A vaccine

The hepatitis A vaccine (HAV) is recommended for IBD patients, given that they are more likely to undergo long-term immunosuppressive therapy [50]. Vaccination for HAV has been mandatory in South Korea since 2015. However, a recent study showed that many young IBD patients are not immune to HAV [54]. Thus, it is necessary to check whether a patient has immunity to HAV at IBD diagnosis. If a patient with IBD is not immune to HAV (i.e., is negative for anti-HAV immunoglobulin G [IgG] Ab), they should receive two doses of the HAV vaccine, at 0 and 6–18 months. As with other vaccines, the optimal time to vaccinate is at IBD diagnosis or before the start of immunosuppressive therapy [50].

Human papillomavirus vaccine

The association between IBD and cervical dysplasia/cancer is uncertain. However, the risk seems to increase in patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, such as those taking corticosteroids, immunomodulators, or anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents [14,25]. Many guidelines recommend the human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV) for all males and females aged 18 to 26 years [15,55], which also applies to same-aged patients with IBD [14]. Although recently published Canadian guidelines do not recommend HPV vaccination for individuals aged 27 to 45 years, it should be considered depending on the patient’s risk factors (possibility of a new sex partner or future immunosuppressive therapy) and preferences [14,16,56]. In a small study, HPV vaccination resulted in favorable immunogenicity and no serious adverse events in female patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy [57].

Tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccine

The risk of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP) infection in patients with IBD is unknown. Guidelines recommend age-appropriate vaccination for DTP, including booster doses as needed, in patients with IBD, regardless of their immune status [14,15,25]. Several studies have reported an impaired immunological response to DTP vaccination, particularly among patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy [52,58].

Meningococcal vaccine

The prevalence and risk of meningococcal infection in patients with IBD are unknown. Meningococcal disease is rare, but can lead to sepsis, meningitis, and death [25]. Vaccination for meningococcus is recommended in IBD patients with the following risk factors; anatomic or functional asplenia, complement and antibody deficiencies, human immunodeficiency virus infection, traveling to areas with high rates of endemic meningococcal disease or transmission, risk of occupational exposure to Neisseria meningitides, exposure to a confirmed case or outbreak situation, and serving in the military [14]. The benefit of meningococcal vaccination for all IBD patients without risk factors appears to be uncertain given the low incidence of meningococcal disease [14].

LIVE ATTENUATED VACCINES

Measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine

Limited data exist regarding vaccination against MMR in patients with IBD. A recent retrospective cohort in Korea demonstrated that the seropositivity rates of measles and rubella in patients with IBD are generally similar to those of the general population [54]. Vaccination for MMR is recommended for patients with IBD when it is unclear whether two doses of vaccine have been taken [16]. If the individual is not immune according to a serological test for MMR (Table 1), two doses at least 4 weeks apart if not previously vaccinated with the MMR vaccine, or one dose if previously vaccinated, should be administered [13,15,16]. The MMR vaccine should be avoided in patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, as this is a live attenuated vaccine [13].

Varicella vaccine

Primary varicella infection is more likely to be fatal in patients with IBD, particularly those treated with immunosuppressive therapy [59–61]. Guidelines recommend screening for previous infection or vaccine history-taking at the initial visit, and vaccination if patients are naïve [13,25]. The vaccine can be administered to IBD patients following the principle of live vaccination. However, it should be avoided in patients currently undergoing immunosuppressive therapy [13,62].

Herpes zoster vaccine

HZ, also called shingles, is caused by reactivation of the latent varicella-zoster virus. Previous studies have shown that patients with IBD have an increased risk of HZ compared to the general population [26,63–65]. The risk of HZ is even greater in IBD patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy with thiopurines, corticosteroids, or anti-TNF agents compared to those who are not and the general population [26,64]. Among the new drugs, tofacitinib [66], an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, is associated with an increased risk of HZ, while ustekinumab [67] and vedolizumab are not [68].

Guidelines recommend HZ vaccines for patients ≥ 50 years with IBD. There are two types of HZ vaccines, live attenuated (Zostavax, Merck & Co. Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA) and inactivated adjuvant recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV, Shingrix, GlaxoSmithKline plc, London, England); the latter is preferred because of its superior efficacy and safety. Moreover, it significantly reduces the risk of HZ (by > 90%) [69]. RZV was approved for use in Korea in September 2021. This inactivated vaccine can be safely administered to immune-compromised patients and evokes a good immunogenic response [70,71]. IBD patients aged < 50 years may benefit from RZV [16]. RZV is also recommended for those who have already been vaccinated with the live attenuated vaccine [72]. However, long-term data on the durability of the RZV in patients < 50 years are lacking, so it is necessary to discuss its use in IBD patients aged < 50 years [14].

COVID-19 VACCINE

IBD patients are concerned about the effects of their disease, and associated medications, on the risk of contracting COVID-19 [73]. However, patients with IBD do not have an increased risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection [74], and COVID-19 outcomes do not seem to be worse in IBD patients except in cases with recent steroid use [75]. COVID-19 symptoms in patients with IBD are similar to those of the general population [76]. The SARS-CoV-2 virus binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme II receptor and causes gastrointestinal symptoms [77]. Thus, caution is required because it is challenging to distinguish COVD-19 gastrointestinal symptoms from an IBD flare-up [78].

All guidelines recommend COVID-19 vaccination for IBD patients at the earliest opportunity [35,78,79]. All currently authorized COVID-19 vaccines are available for patients with IBD because they are non-live vaccines [35]. Adverse events associated with the COVID-19 vaccine occur at a similar (or lower) rate in IBD patients and the general population [80]. The COVID-19 vaccine is not related to disease flare-up in patients with IBD [81]. Patients with IBD should keep taking their medications at the time of COVID-19 vaccination, even if they are on an immunomodulatory regimen [35,78,79]. For patients taking high-dose systemic corticosteroids, as it is important to achieve an adequate immune response to the COVID-19 vaccine, the timing should be discussed with the healthcare provider [35,79].

Recent data demonstrate that IBD patients taking an anti-TNF agent or immunosuppressant can achieve immunity following the second dose of vaccine, while the immune response is blunted following a single dose [82]. However, waning of the immune response over time in infliximab-treated patients following two doses of the vaccine emphasizes the need for a third dose [83]. Based on the latest evidence (from April 5, 2022), healthcare providers should recommend the primary series and a booster vaccine for patients with IBD.

In early 2022, a fourth dose of the vaccine was authorized and implemented for elderly and immunocompromised people in some countries [84]. Thus, a second booster vaccine is available in a subset of patients with IBD (i.e., those treated with high-dose corticosteroids [equivalent to ≥ 20 mg prednisolone per day], anti-TNF or other biologics). However, additional data are needed to determine whether the second booster is appropriate for IBD patients.

CONCLUSIONS

As treatments for IBD continue to evolve, healthcare providers need to maintain an up-to-date understanding of potential health issues affecting patients’ daily lives. Vaccination is one of the most important healthcare interventions for patients with IBD. This review will help healthcare providers recognize the importance of vaccination, such that patients will be more likely to receive safe and effective vaccinations.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the research promoting grant from the Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center in 2019.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.