Omics-based biomarkers for diagnosis and prediction of kidney allograft rejection

Article information

Abstract

Kidney transplantation is the preferred treatment for patients with end-stage kidney disease, because it prolongs survival and improves quality of life. Allograft biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing allograft rejection. However, it is invasive and reactive, and continuous monitoring is unrealistic. Various biomarkers for diagnosing allograft rejection have been developed over the last two decades based on omics technologies to overcome these limitations. Omics technologies are based on a holistic view of the molecules that constitute an individual. They include genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. The omics approach has dramatically accelerated biomarker discovery and enhanced our understanding of multifactorial biological processes in the field of transplantation. However, clinical application of omics-based biomarkers is limited by several issues. First, no large-scale prospective randomized controlled trial has been conducted to compare omics-based biomarkers with traditional biomarkers for rejection. Second, given the variety and complexity of injuries that a kidney allograft may experience, it is likely that no single omics approach will suffice to predict rejection or outcome. Therefore, integrated methods using multiomics technologies are needed. Herein, we introduce omics technologies and review the latest literature on omics biomarkers predictive of allograft rejection in kidney transplant recipients.

INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplantation (KT) is the best treatment option for patients with end-stage kidney disease to prolong survival and improve quality of life [1–4]. Since the first KT was conducted in 1954, the surgical technique and immunological knowledge have advanced markedly [5,6]. However, due to increased life expectancy and organ shortages, loss of graft function remains an issue in transplantation [7,8]. A variety of factors are linked to graft survival. However, acute or chronic allograft rejection is the most important risk factor for graft failure [9–11]. Therefore, to avoid rejection and maintain graft function, personalized immunosuppression based on individual monitoring of kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) is required [12–16].

Allograft biopsy and histopathological examination are the gold standard for diagnosing allograft rejection in KTRs; however, allograft biopsy is an invasive, reactive procedure that is challenging to monitor continuously [17]. Moreover, there is marked interobserver disagreement in interpretations of histopathological findings [18]. Other markers of rejection include elevation of serum creatinine and proteinuria, but these are not sensitive or specific for early diagnosis of rejection.

Major recent advances in molecular biology have enabled highresolution sequence mapping of human structural variation [19,20]. Omics-based immunological monitoring and rejection-predicting technologies for KTRs have attracted interest over the last two decades. In this article, we introduce omics technologies for early diagnosis of allograft rejection in KTRs and review the related literature.

OMICS TECHNOLOGIES

Omics technologies are based on a holistic view of the molecules that constitute an individual [21]. They aim primarily at universal detection of genes (genomics), mRNA (transcriptomics), proteins (proteomics), and metabolites (metabolomics) [21]. Generally, omics technologies assess cellular macromolecules in biological samples (e.g., blood, urine, and tissue) in a nonbiased and nontargeted manner [21]. Advances in high-throughput technologies combined with large-scale data acquisition and computational analysis enable study of complete sets of molecules with improved speed, high accuracy, and lower cost compared with repeated single-molecule experiments [20]. Therefore, the omics approach can be applied to disease screening, diagnosis, and prognosis prediction, providing insight into the pathophysiologic basis of disease [21,22]. Omics technologies have accelerated biomarker discovery and provided insight into the multidimensional biological processes implicated in transplantation [20].

Genomics involves sequencing and analyzing the genome of an organism or cell (complete set of DNA). The human genome contains about 3 billion base pairs and approximately 30,000 to 40,000 protein-coding genes [23]. To analyze the genetic contribution to complex diseases, traditionally, genes have been individually analyzed (e.g., candidate gene association studies of the associations between predefined genes and a trait of interest) [24]. However, advanced genomic methodologies such as genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and whole-genome sequencing can simultaneously scan and analyze many genetic variants. GWAS scans using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array data have the benefit of lower cost compared with whole-genome sequencing; however, they have low affinity for rare variants.

The transcriptome refers to all transcripts (both coding RNAs [mRNA] and noncoding RNAs—long noncoding RNA, microRNA [miRNA], small interfering RNA [siRNA], and piwi-interacting RNA [piRNA]) in an individual, and it is the template for protein synthesis via a process termed translation. mRNA plays an intermediary role in protein translation [24]. Therefore, according to its spatial and temporal specificity, the mRNA profile reflects the functions of cells and organisms under specific physiologic or pathophysiologic conditions [25]. Transcriptomics analyzes the whole set of RNA in each cell or organism. This enables identification of active and inactive genes [26]. There are two transcriptomic methodologies—microarrays and RNA sequencing. Microarray technologies are primarily used to analyze predefined RNA targets, whereas RNA sequencing uses deep-sequencing technologies to analyze all sequences in a sample. RNA sequencing, which uses next-generation sequencing, is now widely used for transcriptomics.

The proteome is defined as the set of all proteins in a cell, tissue, or organism [27]. Proteomics analyzes the presence, activity, and interactions of the proteome, and provides insight into the functional network and relevance of proteins [28,29]. This requires the ability to detect thousands of proteins simultaneously, by analyzing the entire proteome of a cell, tissue, or organism [30]. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics allows identification and quantification of proteins and posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, in complex biological samples [31,32]. There are numerous mass-spectrometric techniques for large-scale relative or absolute proteome quantification. These techniques differ in the level of proteome quantification, accuracy, and reproducibility. Therefore, it is essential to select the most suitable mass-spectrometric technique for the investigation of pathophysiologic tissue [30].

Metabolomics is the study of the global metabolite profile of a cell, tissue, or organism under physiologic or pathophysiologic conditions [21]. Metabolomics analyzes chemical processes involving small metabolites (< 1,500 Da) in a sample. Metabolites are the final downstream products of gene transcription, so changes in metabolites are amplified relative to those in the upstream transcriptome and proteome [33]. Theoretically, this represents an advantage of metabolomics over other omics approaches. Moreover, the metabolome, as the downstream product, is the closest to the phenotype of the biological system and can be affected by the environment and microbiome [21]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometry, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry are metabolomic methodologies. NMR spectrometry is useful in clinical practice because it does not require separation or ionization during sample preparation and yields results within a few hours. However, compared with mass spectrometry, the sensitivity is low and fewer metabolites that can be analyzed [34].

OMICS-BASED BIOMARKERS FOR ALLOGRAFT REJECTION IN KIDNEY TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS

Regarding immunological monitoring in KTRs, the most widely used biomarker is donor-specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alloantibodies (DSAs). However, because of advances in immunosuppression, the incidence of de novo DSA is relatively low (15% to 25%) [35–38]. Furthermore, most de novo DSA production cases cause negative allograft outcomes several years after the initial occurrence, so may be associated with subclinical rejection during the early period [24]. Hence, research has focused on identifying non-HLA biomarkers predictive of allograft rejection using omics technologies (Fig. 1). To date, various potential biomarkers have been developed using omics technologies, which we summarize in the sections below.

Advantages of omics biomarkers for prediction and treatment of acute rejection. SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

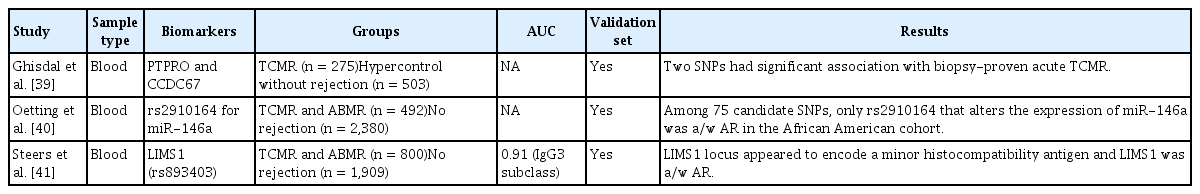

Genomic biomarkers of acute rejection

In a GWAS of European KTRs, Ghisdal et al. [39] used a DNA-pooling approach to compare 275 acute T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) cases and 503 hyper-controls (KTRs who did not show acute rejection [AR] although they had a less favorable HLA match at baseline) from a total of 4,127 KTRs (Table 1). The DNA-pooling approach decreases the number of tests needed and reduces the cost. For validation, 313 TCMR cases and 531 hyper-controls from 2,765 KTRs were used. Among 14 candidate SNPs, two had significant associations with AR—one locus in PTPRO coding for a receptor-type tyrosine kinase essential for B cell receptor signaling and the other encompassing the ciliary gene CCDC67.

American investigators validated 75 candidate SNPs reportedly associated with AR [40]. They used DNA from two multicenter cohorts of KTRs. GWAS data were identified and divided into two subcohorts consisting of 2,390 European American and 482 African-American KTRs, which were analyzed separately. Among 75 candidate SNPs, only rs2910164, which alters the expression of the miRNA miR-146a, showed a significant association with AR in the African-American cohort.

Steers et al. [41] focused on genomic collision situations, wherein transplant recipients carried two copies of a deletion that was not homozygous in the organ donor. They conducted a two-stage (discovery and replication) genetic association study to uncover high-priority copy number variants influencing AR. In the 705 discovery cohort, the LIMS1 locus represented by rs893403 showed a significant association with allograft rejection. This was replicated among the 2,004 donor-recipient pairs after adjustment for the age, sex, ethnicity, and HLA status mismatch of the recipient.

GWAS studies have identified different SNPs associated with AR. The difference may be associated with the heterogeneity and complexity of AR, small size of the cohort, and genetic differences among ethnicities [42]. Also, there may be variation among transplant centers in the SNPs associated with AR [43]. Therefore, a large-scale, multicenter study including various ethnicities is required to evaluate the associations between SNPs and AR.

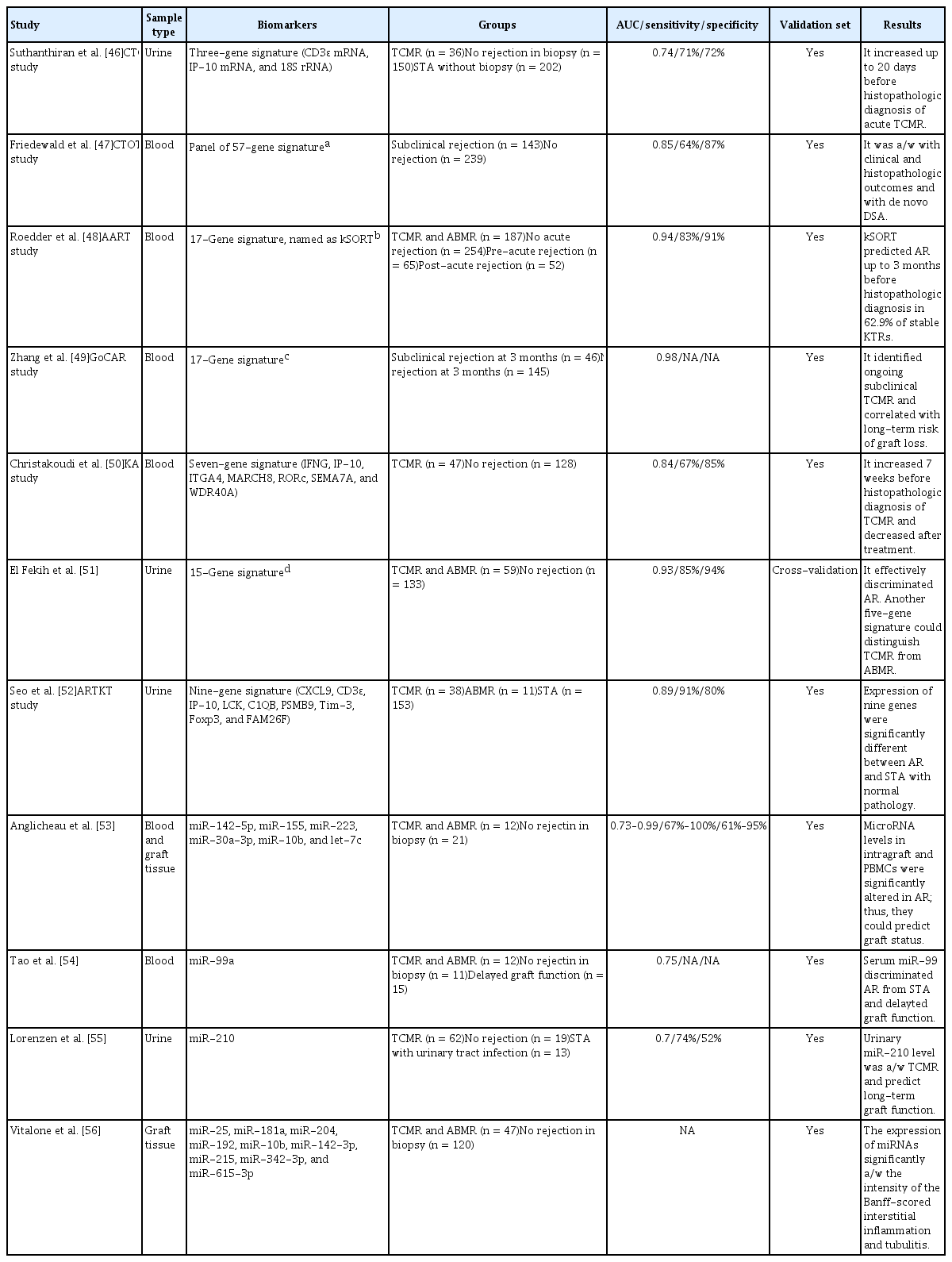

Transcriptomic biomarkers of acute rejection

The Suthanthiran group has suggested that urine mRNA levels could be used to detect AR [44–46]. They analyzed 4,300 urine samples from 485 KTRs in the prospective observational Clinical Trials in Organ Transplantation 04 (CTOT-04) study (Table 2) [46]. The combination of the 18S ribosomal RNA, CD3ɛ, and IP-10 mRNA levels in urinary cells showed utility as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of TCMR. The diagnostic signature markedly increased for up to 20 days before histopathological diagnosis of TCMR.

The CTOT-08 study was designed to develop molecular biomarkers for clinical phenotypes in KTRs [47]. Among 253 KTRs, the investigators used 530 paired peripheral blood samples to discover a novel gene-expression profile predictive of subclinical AR. The classifier consisted of 61 probe-sets that mapped 57 genes. The gene expression profile was significantly correlated with the clinical and histopathologic outcomes, as well as with de novo DSA in two validation sets.

The Assessment of Acute Rejection in Renal Transplantation (AART) study group developed the Kidney Solid Organ Response Test (kSORT) to detect KTRs with a high risk of AR [48]. They analyzed the gene expression data of 558 blood samples from 436 KTRs and selected 17 genes (USP1, CFLAR, ITGAX, NAMPT, MAPK9, RNF130, IFNGR1, PSEN1, RYBP, NKTR, SLC25A37, CEACAM4, RARA, RXRA, EPOR, GZMK, and RHEB) that could discriminate AR. kSORT predicted AR up to 3 months prior to histopathologic diagnosis in 62.9% of stable KTRs, so could be used to predict subclinical rejection.

Zhang et al. [49] examined subclinical histologic and functional changes in KTRs from the prospective Genomics of Chronic Allograft Rejection (GoCAR) study. They used peripheral blood RNA from 191 KTRs who underwent surveillance biopsy 3 months after transplant. A 17-gene signature set (ZMAT1, ETAA1, ZNF493, CCDC82, NFYB, SENP7, CLK1, SENP6, C1GALT1C1, SPCS3, MAP1A, EFTUD2, AP1M1, ANXA5, TSC22D1, F13A1, and TUBB1) was identified as a candidate biomarker of ongoing subclinical TCMR. After extensive validation in an independent cohort of 110 KTRs, this gene set was confirmed to be associated with subclinical TCMR 3 months after transplant, and to be related to an increased risk of long-term graft loss.

Christakoudi et al. [50] developed a multivariable gene-expression signature targeting TCMR using 1,464 peripheral blood samples from 248 patients in the Kidney Allograft Immunological Biomarkers of Rejection (KALIBRE) study. They selected a parsimonious gene-expression signature—the smallest set of genes showing satisfactory predictive performance in the development phase. The selected seven-gene signature (IFNG, IP-10, ITGA4, MARCH8, RORc, SEMA7A, and WDR40A) was confirmed using internal and external KT cohorts. The estimated probability of TCMR increased 7 weeks before histopathologic diagnosis and decreased after treatment.

El Fekih et al. [51] isolated urinary exosomal mRNAs of 192 KTRs (59 rejections) and developed rejection signatures based on differential gene expression. After cross-validation, a 15-gene signature (CXCL11, CD74, IL32, STAT1, CXCL14, SERPINA1, B2M, C3, PYCARD, BMP7, TBP, NAMPT, IFNGR1, IRAK2, and IL18BP) discriminated AR with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.93. Moreover, a five-gene signature (CD74, C3, CXCL11, CD44, and IFNAR2) could differentiate TCMR from active antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) with an AUC of 0.87.

The Korean Assessment of immunologic Risk and Tolerance in Kidney Transplantation (ARTKT) study group reported a transcriptomic biomarker of AR using the urinary mRNA signature of KTRs [52]. Initially, they searched for candidate genes for AR in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and selected 10 genes based on a meta-analysis of four datasets in the GEO database, along with four genes from the literature. Among these 14 candidate genes for AR, the expression of nine (CXCL9, CD3ɛ, IP-10, LCK, C1QB, PSMB9, TIM-3, FOXP3, and FAM26F) differed significantly between AR and stable KTRs in the validation set. The final AUC value of the nine-gene signature was 0.84 in the validation model.

The associations between miRNAs and AR have been analyzed. Anglicheau et al. [53] reported alterations of miRNA expression in KTRs with AR. They analyzed the expression of miRNAs in allograft tissue and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in 33 KTRs (12 with AR) using the TaqMan low-density array. Among the identified miRNAs, miR-142-5p, miR-155, and miR-223 were increased, and miR-30a-3p, miR-10b, and let-7c were decreased, in KTRs with AR compared to KTRs with stable graft function. Therefore, patterns of miRNA expression can serve as biomarkers of allograft status.

Tao et al. [54] analyzed miRNA profiles in blood samples from 33 KTRs (12 with AR; 11 with stable control; and 15 with delayed graft function). The TaqMan miRNA assay showed that miR-99a, miR-100, miR-151a, let-7a, let-7c, and let-7f were altered in the serum of KTRs with AR. Among these six miRNAs, miR-99a and miR-100 were significantly upregulated in KTRs with AR compared to the stable controls. In KTRs with delayed graft function, miR-99a could discriminate AR from both stable graft function and delayed graft function.

Lorenzen et al. [55] profiled the urinary miRNAs of 81 KTRs (62 TCMR and 19 stable control). The TaqMan miRNA assay showed that miR-10a, miR-10b, and miR-210 were markedly deregulated in urine of KTRs with TCMR. Among them, only miR-210 differed between KTRs with TCMR compared to stable control KTRs. In addition, a decreased miR-210 level was associated with a greater rate of decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate at 1 year after transplant. Therefore, the urinary miR-210 level could identify KTRs with AR and predict long-term graft function.

Vitalone et al. [56] analyzed the graft tissue of 167 KTRs (47 with AR and 120 without rejection) to understand the molecular pathophysiology of alloimmune injury. They transcriptionally profiled miRNAs by multiplexed microfluidic quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Nine relevant miRNAs (miR-25, miR-181a, miR-204, miR-192, miR-10b, miR-142-3p, miR-215, miR-342-3p, and miR-615-3p) were identified only in the AR group. The expression levels of these miRNAs were significantly associated with histopathological interstitial inflammation and tubulitis intensity.

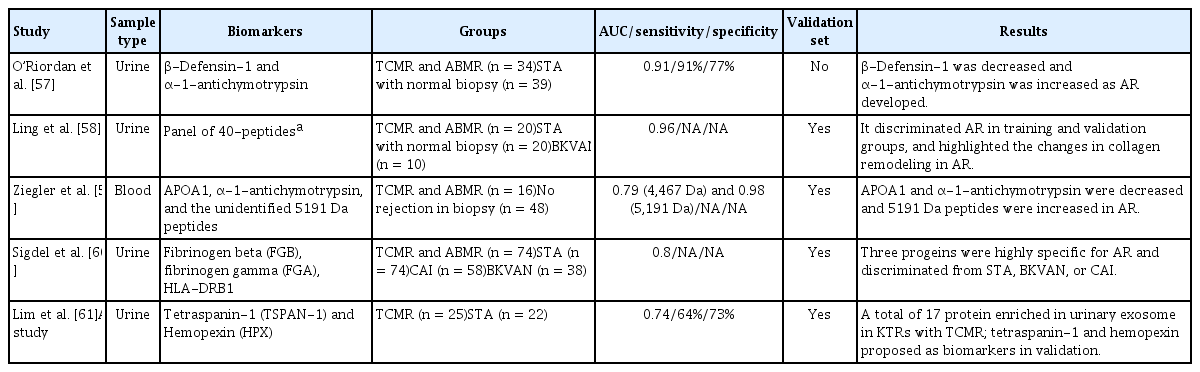

Proteomic biomarkers of acute rejection

Several plasma and urine proteomic studies have revealed proteomic biomarkers associated with AR (Table 3). O’Riordan et al. [57] analyzed the urinary proteome of 73 KTRs (34 with AR and 39 with stable graft function). As AR developed, β-defensin-1 was decreased and α-1-antichymotrypsin was increased. Therefore, the ratio of β-defensin-1 to α-1-antichymotrypsin in urine may be a novel proteomic biomarker for AR.

Ling et al. [58] performed a urine proteomic analysis of 70 samples from 50 KTRs and 20 healthy controls. A panel of 40 peptides for AR was identified, which discriminated AR in the validation cohort (AUC = 0.96). Moreover, a mechanistic analysis based on peptide sequencing implicated proteolytic degradation of uromodulin and collagens, such as COL1A2 and COL3A1.

Ziegler et al. [59] analyzed blood samples from 64 KTRs to identify biomarkers of AR. Among the 22 candidate proteins, APOA1, α-1-antichymotrypsin, and an unidentified 5191 Da peptide were associated with TCMR.

Sigdel et al. [60] used isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ)-based proteomic discovery and targeted enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) validation to discover and validate candidate urine proteomic biomarkers from 262 KTRs with biopsy-proven graft injury. Among the 69 urine proteins whose abundance differed significantly between the AR and stable graft function groups, nine (HLA-DRB1, FGG, FGB, FGA, KRT14, HIST1H4B, ACTB, KRT7, and DPP4) were associated with stable graft function, BK virus nephropathy, and chronic allograft injury (p < 0.01; fold increase > 1.5). Among these nine proteins, three (FBG, FGG, and HLA-DRB1) were validated as candidate biomarkers for AR.

Lim et al. [61] performed a proteomic analysis to identify candidate biomarkers for TCMR diagnosis in urinary extracellular vesicles using urine samples collected for the ARTKT study. They performed a proteomic analysis by nanoliquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and selected five proteins as candidate biomarkers for early diagnosis of acute TCMR. Subsequently, they validated the protein levels of the five candidate biomarkers by western blot analysis. Of them, the tetraspanin-1 and hemopexin levels were significantly higher in KTRs with TCMR.

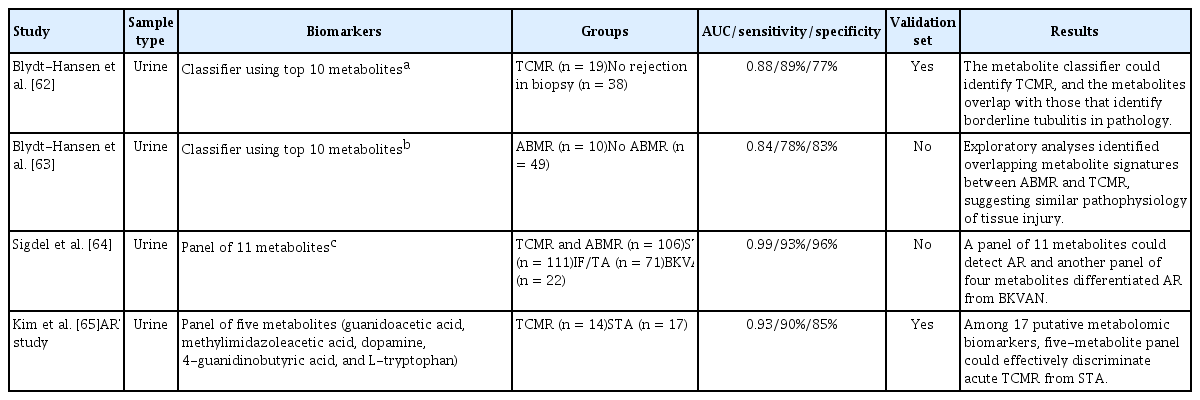

Metabolomic biomarkers of acute rejection

Initially, metabolomic studies used NMR spectrometry, but this has been gradually replaced by mass spectrometry for blood and urine samples. The Blydt-Hansen group discovered urinary metabolomic biomarkers of TCMR by analyzing 277 urine samples from 57 KTRs (Table 4) [62]. Among 134 unique metabolites, the selection of the top 10 most important metabolites was internally validated (AUC = 0.88). They also identified urinary metabolomic biomarkers of ABMR [63] by analyzing 396 urine samples from 59 KTRs. They found 133 metabolites related to ABMR, and the top 10 metabolites were selected as a urine metabolomic signature for ABMR. The urine metabolite signature had an AUC of 0.84 for discriminating ABMR, and internal validation yielded an AUC of 0.76.

Sigdel et al. [64] analyzed the metabolomic profiles of biopsy-matched urine samples from 310 KTRs (106 AR). They identified 266 metabolites; a panel of 11 metabolites (glycine, glutaric acid, adipic acid, inulobiose, threose, sulfuric acid, taurine, N-methylalanine, asparagine, 5-aminovaleric acid lactam, and myo-inositol) enabled detection of AR. The AUC for discriminating AR from stable graft function was 0.99, with 92.9% sensitivity and 96.3% specificity.

The ARTKT study group developed a urinary metabolomic biomarker for TCMR [65]. They identified 17 putative metabolites that were altered in TCMR compared with stable graft function, and discovered five urinary metabolomic biomarkers (guanidoacetic acid, methylimidazoleacetic acid, dopamine, 4-guanidinobutyric acid, and L-tryptophan) of TCMR. Their ability to predict TCMR was excellent, with an accuracy of 87.0% (AUC = 0.926, sensitivity = 90.0%, specificity = 84.6%).

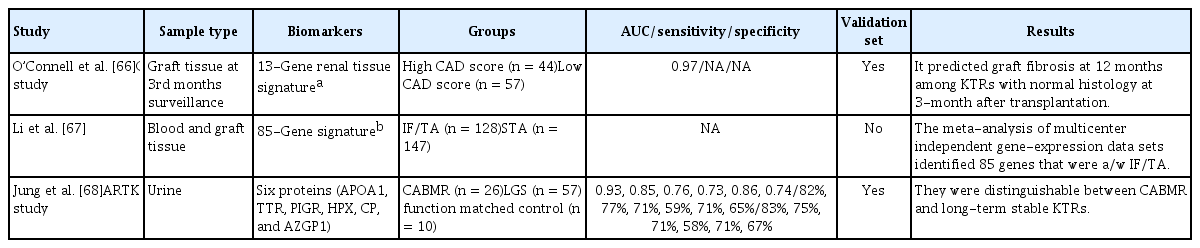

Omics biomarkers for chronic allograft injury and chronic rejection

There are various omics biomarkers for chronic allograft injury and chronic active antibody-mediated rejection (CABMR) (Table 5). The GoCAR group prospectively analyzed the gene-expression profiles of 159 tissue samples from KTRs with stable graft function at 3 months after transplantation [66]. They identified a set of 13 genes (CHCHD10, KLHL13, FJX1, MET, SERINC5, RNF149, SPRY4, TGIF1, KAAG1, ST5, WNT9A, ASB15, and RXRA) independently predictive of allograft fibrosis 12 months after transplantation. The 13-gene graft signature was validated in an independent cohort (n = 45, AUC 0.87) and two independent expression datasets (n = 282, AUC = 0.83; n = 24, AUC = 0.97, respectively).

Li et al. [67] performed a meta-analysis of molecular datasets of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IF/TA) in the GEO database from peripheral blood and allograft biopsy samples. They identified a robust typical transcriptional response in IF/TA involving 85 significantly differentially expressed genes compared with non-IF/TA.

The ARTKT study group identified potential urinary extracellular vesicle protein biomarkers of CABMR [68]. They used a proteomic approach to measure changes in urinary extracellular vesicles in urine samples from 93 KTRs (CABMR, n = 26). Six proteins (APOA1, TTR, PIGR, HPX, AZGP1, and CP) enabled discrimination of the CABMR and long-term graft survival groups. AZGP1 was a CABMR-specific biomarker that enabled differentiation of the rejection-free control group based on age at transplant, time since KT, and graft function.

Limitations and future directions

Advances in high-throughput omics technologies have facilitated the discovery of biomarkers in the transplant field. However, there are several barriers to their clinical application. The key features of a biomarkers of AR in KTRs are noninvasiveness, ease of measurement and interpretation, reproducibility, high sensitivity and specificity, good prognostic performance, and cost-effectiveness [69–72]. Prospective randomized controlled trials to assess the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of candidate omics biomarkers compared with traditional diagnostic methods are required for clinical application of biomarkers. In addition, considering the complexity and heterogeneity of rejection, large cohorts are needed to overcome the problem of inconsistent omics biomarkers among studies. A meta-analysis using the same type of data from different cohorts would go some way to overcoming this limitation.

Another requirement for the clinical application of omics biomarkers is integration. Noninvasive omics biomarkers show promise not only for diagnosis of rejection, but also for early diagnosis of histopathological injuries, such as subclinical AR, as well as stratifying patients according to the risk of rejection to reduce the need for surveillance biopsies. However, rejections (TCMR and ABMR) are heterogeneous in terms of severity and underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms, so it is difficult to determine the status of an individual patient using a single omics method developed based on a small sample size. Moreover, the expression of a given gene set does not indicate the total amount of proteins produced, their biological activities, or the functions of metabolites [73]. Hence, the predictive performances of omics biomarkers differ among cohorts [74]. Therefore, to assess the pathophysiologic and immunological responses associated with AR and long-term stable graft function, multidimensional multiomics approaches are needed. Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data are typically produced on an individual basis and analyzed separately [24]. The application of artificial intelligence (AI) through machine-learning algorithms and neural networks may be the solution. AI models enable analysis and integration of large-scale molecular information [69,75,76], including complex multiomics data. This will provide insight into the mechanisms of AR and long-term graft survival.

CONCLUSIONS

Omics biomarkers are the cornerstone of precision medicine in KT; they can guide selection of the best treatment by integrating traditional clinical information and tailoring immunosuppression. Integration of individual omics analyses may be critical for deciphering complex biological and immunological systems in transplantation. Therefore, large-scale prospective studies using multiple omics biomarkers are warranted.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Han Byeol Sim for improving the quality of the figure. This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI15C0001), and supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1I1A3047973 and 2021R1I1A3059702).

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.