Role of Akt1 in renal fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation during the progression of acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is an underestimated yet important risk factor for the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD), characterized by tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation. Tubular dedifferentiation, which is associated with the loss of epithelial markers and the gain of mesenchymal features, is thought to be involved in tubulointerstitial fibrosis. As protein kinase B/Akt is involved in the development of CKD, we investigated the role of Akt1, one of the three Akt isoforms, in a murine model of AKI-to-CKD progression.

Methods

We subjected C57BL/6 male mice to unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (UIRI) and harvested their kidneys after 6 weeks. Mice were divided into four groups, namely, wild-type (WT) UIRI, Akt1−/− UIRI, WT sham, and Akt1−/− sham.

Results

Akt1 (but not Akt2 or Akt3) was markedly activated in WT UIRI mice than in WT sham mice. Tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation significantly increased in WT UIRI mice, but were attenuated in Akt1−/− UIRI mice. Both WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice showed markedly upregulated transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1)/Smad signaling compared with WT sham mice. However, TGF-β1/Smad expression did not differ between the two groups. The levels of phosphorylated GSK-3β, β-catenin, and Snail were attenuated in Akt1−/− UIRI mice compared with those in WT UIRI mice.

Conclusions

Deletion of Akt1 results in the attenuation of renal fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation, independent of TGF-β1/Smad signaling, during AKI-to-CKD progression in a UIRI without contralateral nephrectomy model. Thus, Akt1 may serve as a therapeutic target in AKI-to-CKD progression.

INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common syndrome reported in 5% of the hospitalized and more than 30% of the critically ill patients [1]. Despite advances in medical care, AKI is one of the most common and serious complications in hospitalized patients, and is associated with high rates of adverse outcomes during hospitalization and after discharge [2,3]. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is another major concern associated with high mortality and morbidity [4]. Although AKI and CKD were considered to be distinct pathologies, recent epidemiological and mechanistic studies suggest that they are closely interconnected as AKI frequently leads to CKD, regardless of the cause of acute injury [5]. Thus, a better understanding of the progression from AKI-to-CKD is warranted to develop suitable interventions.

AKI-to-CKD progression is a complex process that is poorly understood [6]. Recent experimental studies have suggested an interplay between endothelial dysfunction, interstitial inflammation, fibrosis, and tubular epithelial injury underlying AKI-to-CKD progression [7]. It has been proposed that injured tubular epithelial cells (TECs) play a central role in AKI-to-CKD progression [7–9], and drive inflammation by producing pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [10]. In addition, TECs contribute to renal fibrosis via epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process in which epithelial cells lose their polarity and adhesion properties, and gain migratory and invasive properties to become mesenchymal cells [7–9,11]. However, the contribution of EMT to kidney fibrosis remains controversial, as studies using genetic cell lineage tracing could not find evidence of direct contribution of epithelial cells to the myofibroblast population [8]. Thus, in this manuscript, change of TEC upon kidney injury was expressed as tubular dedifferentiation, which refers to EMT-like morphological changes leading to reduced expression of epithelial markers and increased expression of mesenchymal markers. Although the extent to which EMT contributes to kidney fibrosis is yet to be fully elucidated, tubular dedifferentiation prompts one to appreciate the role of TECs in kidney fibrosis [11].

Akt/protein kinase B (PKB) is a serine/threonine kinase, activated by phosphatidylinositide 3′-OH kinase (PI3K); it is a key regulator of cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and metabolism [12,13]. Mammals express three Akt isoforms, Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3, that differ in their functions. While Akt1 is ubiquitously expressed, Akt2 expression is high in insulin-responsive tissues such as adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle, and Akt3 is highly expressed in the brain [13]. In the kidneys, Akt is involved in the proliferation and activation of interstitial fibroblasts, glomerular mesangial cells, and TECs during the development of renal fibrosis [12]. Evidence also indicates that the Akt signaling pathway plays a role in tubular dedifferentiation [11,12].

The exact isoform(s) of Akt associated with tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation during AKI-to-CKD progression remains unknown. In the present study, we established a unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (UIRI) without contralateral nephrectomy, a validated model of AKI-to-CKD progression with extensive tubulointerstitial fibrosis [14], and investigated the role of Akt isoforms in tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation during AKI-to-CKD progression.

METHODS

Murine model of AKI-to-CKD progression

All animal studies were performed with the approval of the Pusan National University–Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (PNU-2016-1399). All procedures were conducted as per the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals, endorsed by the Korean Society of Experimental Animal. Male wild-type (WT) mice (C57BL/6) were purchased from Koatech Technology Corporation (Seoul, Korea), and male mice lacking Akt1 (Akt1−/−) (C57BL/6, 129P2-Akt1tm1Mbb/J) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All mice (8-week-old) were housed in cages at 22°C under a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and had ad libitum access to standard laboratory diet and water.

To establish a murine model of AKI-to-CKD progression, UIRI was induced without contralateral nephrectomy in WT and Akt1−/− mice. Briefly, each mouse was anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation, and the left kidney was exposed through a left flank incision. The left renal hilus was separated from the surrounding tissue by gentle dissection. UIRI was induced by the placement of an atraumatic microaneurysm clamp (Fine Science Tools, Cambridge, UK) on the renal pedicle for 30 minutes. The clamp was removed, and reperfusion was visually confirmed by a change in color from dark purple to red. The kidney was placed back in the correct anatomical position, and the incision was closed. The mice were placed on a heating pad (37°C) throughout the surgery. After surgery, 1 mL warm saline was intraperitoneally injected for volume substitution. Sham-operated mice were subjected to identical surgical procedures without clamping of the left renal pedicle. Mice were then divided into four groups as follows: WT UIRI (n = 6), Akt1−/− UIRI (n = 6), WT sham (n = 6), and Akt1−/− sham (n = 6).

Tissue preparation

Six weeks after surgery, mice were euthanized; their left kidneys were perfused with cold (4°C) phosphate-buffered saline and immediately excided. One-half of the left kidney was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C for protein and mRNA analyzes. The other half was fixed in 10% neutralized formalin at room temperature, and embedded in paraffin for histological analyzes and immunohistochemistry.

Histological analyzes

Paraffin-embedded kidney tissues were sectioned into 4-μm thick samples for light microscopy. As previously described [15], periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Masson’s trichrome (MT) staining were performed to assess tubulointerstitial damage and interstitial fibrosis. Tubular damage in PAS-stained sections was examined by a blinded observer in a minimum of 20 cortical fields (×200 magnification). Tubular damage was estimated on the basis of tubular dilation, tubular atrophy, tubular cast formation, sloughing of TECs, or loss of brush border and thickening of tubular basement membrane using the following scoring scale: 0, no tubular damage; 1, < 10% of tubules damaged; 2, 10% to 25% of tubules damaged; 3, 25% to 50% of tubules damaged; 4, 50% to 75% of tubules damaged; and 5, > 75% of tubules damaged [16]. For quantification of interstitial fibrosis, a blinded observer examined at least 20 cortical fields (×200 magnification) of MT-stained sections and graded interstitial fibrosis as follows: 0 = no evidence of interstitial fibrosis; 1, < 25% involvement; 2, 25% to 50% involvement; 3, > 50% involvement [16].

Immunohistochemistry

As previously described [15], immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed 3-μm-thick paraffin-embedded sections. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated using an ethanol series, blocked with normal horse serum, treated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, and incubated for 30 minutes with a secondary antibody (ImmPRESS HRP reagent kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The slides were developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Vector Laboratories) and counterstained with Harris hematoxylin. The primary antibodies used were anti-phosphorylated Akt1 (p-Akt1) (ab5954, 1:200, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-E-cadherin (#3195, 1:400, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) (ab190503, 1:500, Abcam), anti-phosphorylated glycogen synthase kinase-3β (p-GSK-3β) (ab131097, 1:100 dilution, Abcam), anti-β-catenin (#9562, 1:400, Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-Snail (sc-271977, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Staining intensity was semi-quantitatively graded in a blinded manner using the following scoring scale: 0 = absence of specific staining; 1, < 25% area with specific staining; 2, 25% to 50% staining; 3, 50% to 75% staining; 4, > 75% staining. At least 20 fields of renal cortex were investigated [16].

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed as previously described [15]. Proteins were extracted from kidney sections using a protein extraction solution (PRO-PREP, iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea), and protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Protein Assay, Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins were separated by electrophoresis on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, NJ, USA), which were blocked for 2 hours at room temperature with 5% (w/v) non-fat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline (10 mM Tris/HCl [pH 8.0] and 150 mM NaCl) containing 0.05% Tween-20. Membranes were immunoblotted with the following primary antibodies: anti-Akt1/anti-p-Akt1/anti-Akt2/anti-p-Akt2/Akt3 (#2938/#9018/#3063/#8599/#4 059, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-E-cadherin (#3195, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-vimentin (#5741, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; ab5694, 1:1,000, Abcam), anti-TGF-β1 (#3711, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-small mothers against decapentaplegic 2 (Smad2)/p-Smad2/Smad3/p-Smad3 (#5339/#3108/#9523/#9520, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-GSK-3β/anti-p-GSK-3β (#12456/#9336, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-β-catenin (#9562, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-Snail (sc-271977, 1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Thereafter, blots were probed using a corresponding horseradish peroxide-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G antibody (1:10,000, Enzo Life Science, Farmingdale, NY, USA). Immunoreactive proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and exposed to film. The area of each band was analyzed using the National Institutes of Health image software (ImageJ). Protein expression was measured by quantifying the relative expression of target protein versus β-actin.

Real-time reverse-transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed as previously described [15]. The expression of β-actin as a housekeeping internal control was quantified in parallel with target genes, and all products were verified using melt curve analysis (95°C 15 seconds, 60°C 15 seconds, and 95°C 15 seconds). Normalization and fold-change value for each gene were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The primers used were as follows: β-actin sense 5′-CTCTCTTCCAGCCTTCCTTCC-3′ and antisense 5′-CTCCTTCTGCATCCTGTCAGC-3′; TGF-β1 sense 5′-CAACAATTCCTGGCGTTACCT TG G-3′ and antisense 5′-GAAAGCCCTGTATTCCGTCTCCTT-3′; E-cadherin sense 5′-GCGTTCTGCCAGAGAAACC-3′ and antisense 5′-TGGATCCAAGATGGTGA TGA-3′; vimentin sense 5′-CACTAGCCGCAGCCTCTATTC-3′ and antisense 5′-GTCCACC GAGTCTTGAAGCA-3′; α-SMA sense 5′-CTGACAGAGGCACCACTGAA-3′ and antisense 5′-CATCTCCAGAGTCCAGCACA-3′.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used for comparison between groups. All statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

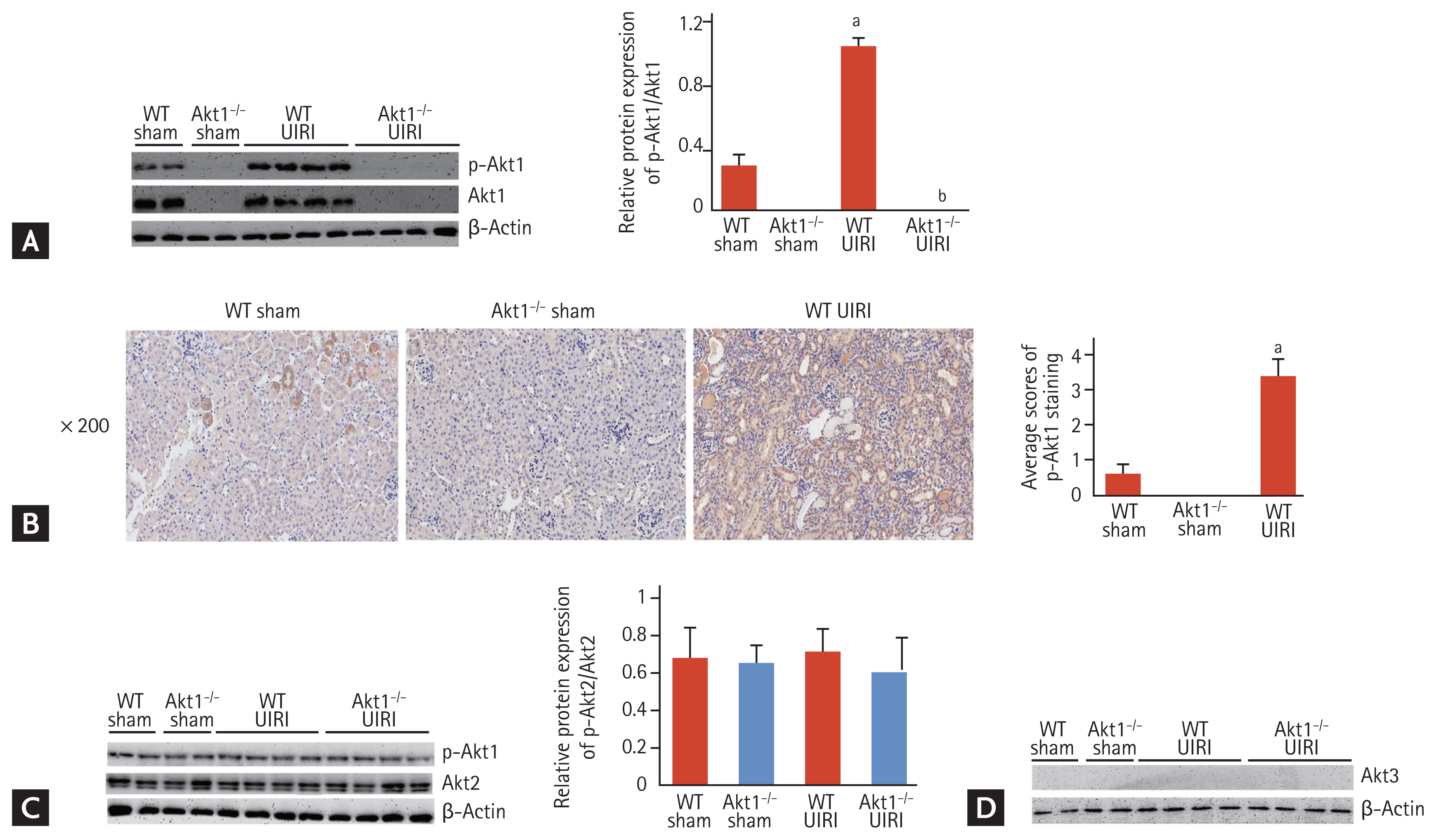

Akt1 is activated in the model of AKI-to-CKD progression

To verify the exact Akt isoform activated in the AKI-to-CKD progression model, we first examined the expression of Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3 in the UIRI kidneys from the four groups. Six weeks after UIRI, the levels of p-Akt1 were elevated in WT UIRI mice compared to those in WT sham mice (Fig. 1A). Immunohistochemical analysis for p-Akt1 also revealed increased levels in the renal tubules of WT UIRI mice compared with those in the renal tubules of WT sham mice (Fig. 1B). However, Western blot analysis showed similar p-Akt2 levels among the four groups (Fig. 1C). Although only Akt1 and Akt2 are known to be expressed in the kidneys [17], we investigated the expression of Akt3 in the UIRI kidneys from the four groups. In all four groups, no expression of Akt3 was detected (Fig. 1D). Thus, we confirmed that Akt1, but not Akt2, was activated in the AKI-to-CKD progression model.

Activation of Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3 in a murine model of acute kidney injury (AKI)-to-chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression. (A) Representative images of Western blots for phosphorylated Akt1 (p-Akt1). Six weeks after unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (UIRI), the expression of p-Akt1 increased in wild-type (WT) UIRI mice compared to that in WT sham mice. (B) Representative images of immunohistochemistry for p-Akt1 (magnification ×200). The levels of p-Akt1 were higher in the renal tubules of WT UIRI mice than those in the renal tubules of WT sham mice. (C) Representative images of Western blots for p-Akt2. The levels of p-Akt2 were similar among the four groups. (D) Representative images of Western blots for Akt3. No Akt3 expression was detected in all four groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6/group). ap < 0.05 as compared with WT and Akt1−/− sham mice, bp < 0.05 as compared with WT UIRI mice.

Akt1 deletion attenuates tubulointerstitial fibrosis in AKI-to-CKD progression model

Six weeks after UIRI, the left kidneys of WT UIRI mice were atrophied and weighed less than those from WT sham mice. However, the left kidneys of Akt1−/− UIRI mice showed lower a level of atrophy and weighed more than those of the WT UIRI mice (Fig. 2A). Consistent with these findings, WT UIRI mice showed more tubular damage than WT and Akt1−/− sham mice. However, these effects were attenuated in Akt1−/− UIRI mice (Fig. 2B). In MT staining, interstitial collagen deposition markedly increased in WT UIRI mice, but decreased in Akt1−/− UIRI mice (Fig. 2C).

Effect of Akt1 deletion on tubulointerstitial fibrosis in a murine model of acute kidney injury (AKI)-to-chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression. (A) Gross features and weights of unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (UIRI) kidneys. Six weeks after UIRI, the left kidneys of Akt1−/− UIRI mice showed lower levels of atrophy and weighed more than the kidneys of the wild-type (WT) UIRI mice. (B) Representative images of Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining (magnification: ×40 [top], ×200 [middle], and ×400 [bottom]). Akt1−/− UIRI mice showed attenuated tubular damage compared to WT UIRI mice. (C) Representative images of Masson’s trichrome (MT) staining (magnification: ×40 [top] and ×200 [bottom]). Interstitial collagen deposition was attenuated in Akt1−/− UIRI mice when compared with that in WT UIRI mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6/group). LKW, left kidney weight; RKW, right kidney weight. ap < 0.05 as compared with WT and Akt1−/− sham mice, bp < 0.05 as compared with WT UIRI mice.

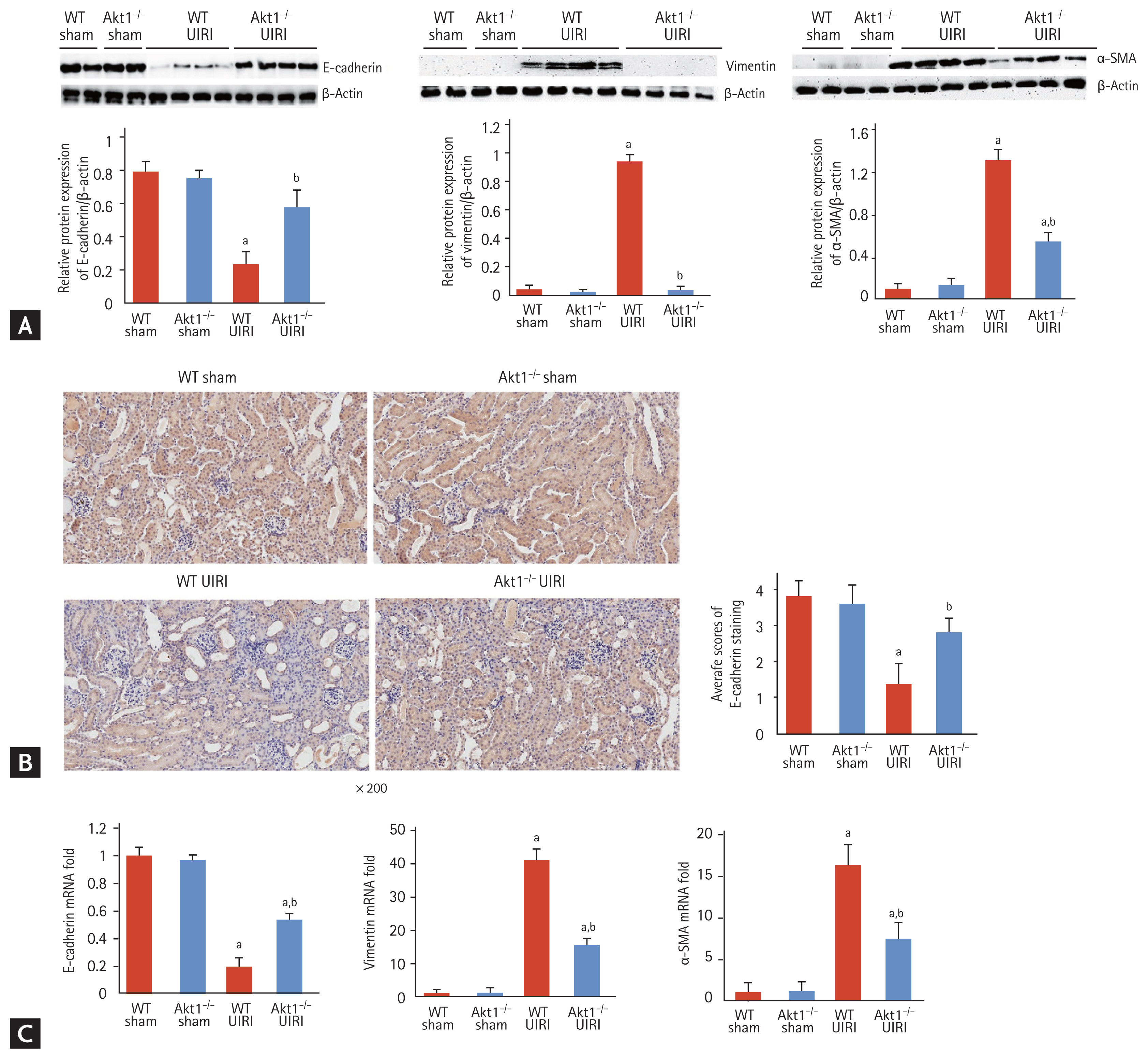

Akt1 deletion attenuates tubular dedifferentiation in AKI-to-CKD progression model

We investigated the effect of Akt1 deletion on the expression of tubular dedifferentiation markers. Western blot analysis revealed a significant decrease in the expression of E-cadherin in WT UIRI mice compared to that in WT and Akt1−/− sham mice; however, E-cadherin expression was higher in Akt1−/− UIRI mice than that in WT UIRI mice (Fig. 3A). Immunohistochemical staining also revealed the higher expression of E-cadherin in Akt1−/− UIRI mice than that in WT UIRI mice (Fig. 3B). Western blot analysis showed that the levels of vimentin and α-SMA were markedly increased in WT UIRI mice compared with those in WT and Akt1−/− sham mice, but these levels were reduced in Akt1−/− UIRI mice (Fig. 3A).

Effect of Akt1 deletion on tubular dedifferentiation in a murine model of acute kidney injury (AKI)-to-chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression. (A) Representative images of Western blots for E-cadherin, vimentin, and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). The expression of E-cadherin was increased in Akt1−/− unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (UIRI) mice compared to that in wild-type (WT) UIRI mice. The expression of vimentin and α-SMA was lower in Akt1−/− UIRI mice than that in WT UIRI mice. (B) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for E-cadherin (magnification ×200). The expression of E-cadherin was higher in Akt1−/− UIRI mice than that in WT UIRI mice. (C) mRNA levels of the genes encoding E-cadherin, vimentin, and α-SMA. The mRNA level of the gene encoding E-cadherin was higher in Akt1−/− UIRI mice than that in WT UIRI mice. The mRNA levels of the genes encoding vimentin and α-SMA decreased in Akt1−/− UIRI mice compared to those in WT UIRI mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6/group). ap < 0.05 as compared with WT and Akt1−/− sham mice, bp < 0.05 as compared with WT UIRI mice.

The mRNA expression of the gene encoding E-cadherin was markedly decreased in WT UIRI mice compared to that in WT and Akt1−/− sham mice, but significantly increased in Akt1−/− UIRI mice compared with that in WT UIRI mice. The mRNA expression of the genes encoding vimentin and α-SMA was markedly higher in WT UIRI mice than that in WT and Akt1−/− sham mice, but was significantly decreased in Akt1−/− UIRI mice compared with that in WT UIRI mice (Fig. 3C).

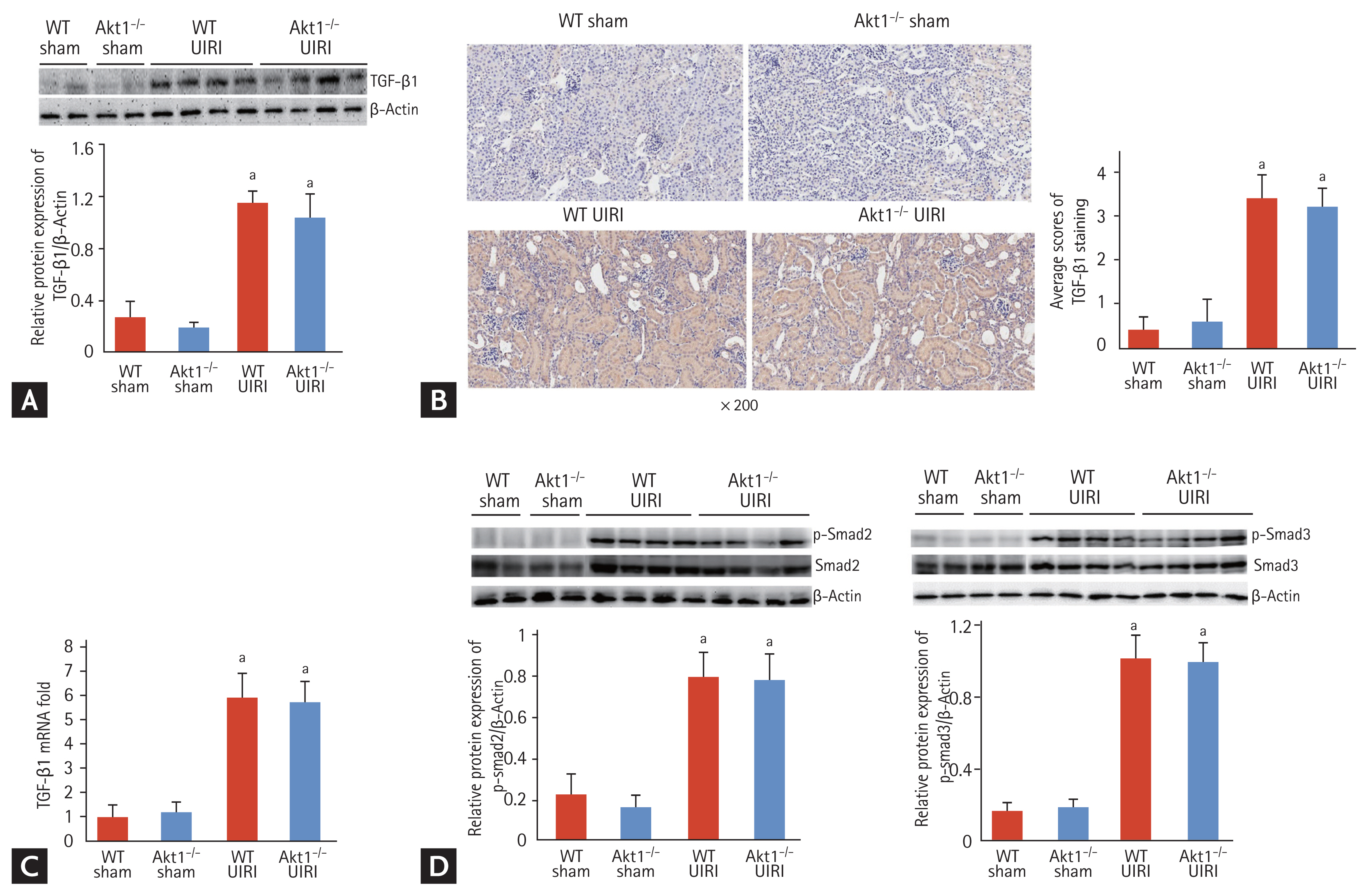

Attenuation of tubular dedifferentiation by Akt1 deletion is independent of TGF-β1/Smad signaling in the AKI-to-CKD progression model

As TGF-β1/Smad signaling is a critical mediator of tubular dedifferentiation and renal fibrosis, we analyzed the expression of TGF-β1 in UIRI kidneys of WT and Akt1−/− mice. Western blot analysis showed that the expression of TGF-β1 was markedly higher in both WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice, but not in WT and Akt1−/− sham mice. However, no difference was observed with respect to TGF-β1 expression between WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the findings of Western blotting, immunohistochemical staining showed no difference in the expression of TGF-β1 between WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the mRNA expression of the gene encoding TGF-β1 showed no difference between WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice (Fig. 4C). We measured the levels of p-Smad2/3 by Western blotting and found them to be increased in both WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice compared with those in WT and Akt1−/− sham mice. However, no difference in the levels of p-Smad2/3 was noted between WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice (Fig. 4D).

Effect of Akt1 deletion on transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)/Smad signaling in acute kidney injury (AKI)-to-chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression model. (A) Representative images of the Western blot for TGF-β1 expression. The expression of TGF-β1 was markedly higher in both wild-type (WT) unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (UIRI) and Akt1−/− UIRI mice than that in WT and Akt1−/− Sham mice. However, no difference in the expression of TGF-β1 was observed between WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice. (B) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for TGF-β1 (magnification ×200). Consistent with the findings of Western blot analysis, there was no difference in the expression of TGF-β1 between WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice. (C) The mRNA level of TGF-β1. There was no difference in the mRNA expression of TGF-β1 between WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice. (D) Representative images of Western blot for p-Smad2/3. The levels of p-Smad2/3 increased in both WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice compared to those in WT and Akt1−/− sham mice. However, no difference was observed in the levels of p-Smad2/3 between WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6/group). ap < 0.05 as compared with WT and Akt1−/− sham mice.

Akt1 deletion attenuates the expression of p-GSK-3β, β-catenin, and Snail during tubular dedifferentiation

During tubular dedifferentiation, Akt can inactivate GSK-3β by direct phosphorylation, leading to the accumulation of β-catenin and Snail [11]. Therefore, we examined the effect of Akt1 deletion on the expression of GSK-3β, β-catenin, and Snail during tubular dedifferentiation. Western blot analysis revealed an increase in the levels of p-GSK-3β in WT UIRI mice compared to those in WT and Akt1−/− sham mice, this effect was attenuated in Akt1−/− UIRI mice (Fig. 5A). The results of immunohistochemistry for p-GSK-3β were consistent with those of the Western blotting (Fig. 5A). Next, we investigated the expression of β-catenin by Western blotting and immunohistochemistry, and found it to be upregulated in WT UIRI mice compared with that in WT and Akt1−/− sham mice; this increase in the expression of β-catenin was reduced in Akt1−/− UIRI mice (Fig. 5B). We analyzed the expression of Snail by Western blotting and immunohistochemistry, and found it to be markedly upregulated in WT UIRI mice compared to that in WT and Akt1−/− sham mice (Fig. 5C); the level of upregulation was attenuated in Akt1−/− UIRI mice.

Effect of Akt1 deletion on the levels of phosphorylated glycogen synthase kinase 3β (p-GSK-3β), β-catenin, and Snail in acute kidney injury (AKI)-to-chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression model. (A) Representative images of Western blots and immunohistochemical staining for p-GSK-3β (magnification ×200). The levels of p-GSK-3β was attenuated in Akt1−/− unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (UIRI) mice compared to those in wild-type (WT) UIRI mice. (B) Representative images of Western blots and immunohistochemical staining for β-catenin (magnification ×200). The expression of β-catenin was alleviated in Akt1−/− UIRI mice when compared with that in WT UIRI mice. (C) Representative images of Western blots and immunohistochemical staining for Snail (magnification ×200). The expression of Snail was decreased in Akt1−/− UIRI mice compared to that in WT UIRI mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6/group). ap < 0.05 as compared with WT and Akt1−/− sham mice, bp < 0.05 as compared with WT UIRI mice.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we illustrated the critical role of Akt1 in renal fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation during AKI-to-CKD progression. We found that Akt1, not Akt2 or Akt3, was activated during AKI-to-CKD progression, and that Akt1 deletion was associated with attenuated tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation. The attenuation of renal fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation caused by Akt1 deletion was independent of the TGF-β1/Smad pathway, and related to the GSK-3β, Snail, and β-catenin pathways.

The UIRI model without contralateral nephrectomy that was established in the present study is a robust system to study AKI-to-CKD progression [14,16,18]. Ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) is a pathological process that aggravates into acute tubulointerstitial injury. Aside from nephrotoxic agents, ischemia is also known to be associated with human AKI. IRI is followed by a repair process, which attempts to restore the normal morphology and function of the kidney; however, in the case of severe injury, it may lead to permanent damage and progressive fibrosis [16]. Thus, it is clinically relevant to analyze IRI for investigating AKI-to-CKD progression. Most experimental studies on renal fibrosis and CKD are performed in a unilateral ureter obstruction model (UUO), which is undoubtedly valuable for investigating the mechanism of AKI-to-CKD transition; however, this model correlates with a rare form of human renal disease [18]. In the UIRI without contralateral nephrectomy model, the contralateral kidney is left intact; this improves the survival, and may even allow the establishment of severe injury [18]. Short-term duration of ischemia (20 minutes) induces mild renal tubulointerstitial injury, and this effect is completely reversed during the acute phase of kidney injury. However, long duration of ischemia (30 or 45 minutes) causes severe tubular damage, apoptosis, and inflammatory infiltration during early disease stages, eventually leading to permanent chronic kidney fibrosis during the later stages (4 weeks after UIRI) [16]. In another study, the injured kidney developed inflammatory cell infiltration and interstitial fibrosis 6 weeks after UIRI (30 minutes ischemia), consistent with a CKD phenotype [18]. Based on the results of these studies, we established a murine model of AKI-to-CKD progression by harvesting injured kidneys 6 weeks after UIRI without contralateral nephrectomy at an ischemia time of 30 minutes.

Previous studies have demonstrated the role of Akt in tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation. In a murine model of UUO, PI3K/Akt activity is increased in ligated kidneys compared to that in non-ligated kidneys [19]. Akt activation is associated with cell proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition in ligated kidneys [19]. Treatment with PI3K inhibitor, Ly294002, was shown to suppress UUO-induced tubulointerstitial fibrosis, as evidenced by decreased expression of fibroblast markers and extracellular matrix deposition in the interstitium [20]. Moreover, Ly294002 reduced the number of proliferating cells in the interstitium and tubules [20]. The role of Akt2 was investigated in renal fibrosis following UUO, and the knockdown of Akt2 was shown to suppress UUO-induced tubulointerstitial fibrosis; indicative of the important function of Akt2 in renal fibrosis following UUO [17]. Akt2 deletion also suppressed UUO-induced tubular dedifferentiation, increased expression of GSK-3β, and decreased Snail and β-catenin levels, suggesting that Akt2 may play an important role in tubular dedifferentiation following UUO [17]. With respect to IRI-induced AKI, Akt phosphorylation was shown to be increased after IRI in mouse kidney, but was reduced upon treatment with a PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin [21]. The proliferation of renal tubular cells increased after IRI in mouse kidney, and this effect was inhibited by wortmannin [21]. These findings suggest that PI3K/Akt signaling is associated with the regulation of renal repair after IRI. Taken together, Akt plays an important role, not only in IRI-induced AKI but also in tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Therefore, we hypothesized that Akt signaling is involved in AKI-to-CKD progression and investigated the role of Akt isoforms in a murine model of AKI-to-CKD progression.

Here, we found that the phosphorylation and activation of Akt1 increased in WT UIRI mice compared to that in WT sham mice, suggesting that, in this model, Akt1 may play an important role in tubulointerstitial fibrosis. However, there is a possibility of compensatory activation of other isoforms (Akt2 or Akt3) that may contribute to tubulointerstitial fibrosis. As Akt3 protein expression is absent in the kidney [17], we investigated the levels of p-Akt2 in WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice and found no difference in the level of p-Akt2 between the two groups. Thus, attenuation of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in Akt1−/− UIRI mice was primarily associated with Akt1 deletion, not with the compensatory activation of Akt2.

During AKI-to-CKD transition, injured TECs may directly contribute to renal fibrosis via EMT [8]. EMT is a biological process that allows a polarized epithelial cell—which normally interacts with the basement membrane through its basal surface—to undergo multiple biochemical changes, enabling it to assume a mesenchymal phenotype characterized by enhanced migratory capacity, invasiveness, elevated resistance to apoptosis, and increased production of extracellular matrix [22]. Thus, EMT is associated with the loss of epithelial markers (E-cadherin, zonular occludens-1, and cytokeratin) and the gain of mesenchymal features (vimentin, α-SMA, fibroblast-specific protein-1, and fibronectin) [8]. Although the present study did not show direct evidence of tubular EMT, it demonstrated an increase in tubular dedifferentiation in WT UIRI mice during AKI-to-CKD progression, consistent with a decrease in the expression of E-cadherin and increase in the levels of vimentin/α-SMA. The genetic deletion of Akt1 resulted in the attenuation of UIRI-induced tubular dedifferentiation, suggestive of the involvement of Akt1 in tubular dedifferentiation during AKI-to-CKD progression.

TGF-β1 signaling plays a crucial role in mediating renal fibrosis [11]. TGF-β1 exerts its pathological activities via Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signaling pathways [11,23]. In the Smad-dependent pathway, the binding of TGF-β1 to its receptor leads to the phosphorylation of Smad2/3. The p-Smad2/3 complex then translocates into the nucleus to regulate the transcription of fibrotic markers [11,23]. The Smad-independent TGF-β1 signaling pathway involved in renal fibrosis includes RhoA, p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase, and PI3K/Akt [23]. In the present study, we found that the levels of TGF-β1 and p-Smad2/3 increased in both WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice compared to those in WT sham mice, suggesting upregulation of TGF-β1/Smad signaling during AKI-to-CKD progression. However, Western blot analysis showed no difference in the expression of TGF-β1 and p-Smad2/3 between WT UIRI and Akt1−/− UIRI mice. Immunohistochemistry and real-time PCR further demonstrated a lack difference in TGF-β1 expression between the two groups. Thus, the attenuation of tubular dedifferentiation and renal fibrosis by the genetic deletion of Akt1 may not be associated with TGF-β1/Smad signaling. Indeed, the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway functions independently to modulate EMT in cancer cells, and has attracted attention as a potential target for the prevention and treatment of metastatic tumors [24]. Taken together, we suggest that Akt1 plays an independent role in tubular dedifferentiation and renal fibrosis, regardless of TGF-β1/Smad signaling, during AKI-to-CKD progression. Further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The present study provides an insight into the mechanism underlying Akt1-mediated tubular dedifferentiation during AKI-to-CKD progression. GSK-3β is a downstream target of PI3K/Akt signaling, which is necessary for maintaining the epithelial architecture [25]. Activation of PI3K/Akt results in the induction of the phosphorylation and functional inactivation of GSK-3β [26,27]. GSK-3β inhibition is implicated in EMT in various epithelial cells, including breast and skin cells [27]. In rat kidney epithelial cells, inhibition of PI3K/Akt activity attenuates TGF-β1-mediated tubular dedifferentiation by decreasing GSK-3β phosphorylation [26]. In the present study, GSK-3β phosphorylation increased in WT UIRI mice during AKI-to-CKD progression, but was decreased in Akt1−/− UIRI mice. Our findings suggest that the decrease in GSK-3β phosphorylation following genetic deletion of Akt1 may result in the attenuation of tubular dedifferentiation during AKI-to-CKD progression. Snail is a transcription factor that binds to the promoter region of E-cadherin and suppresses E-cadherin mRNA production [27]. In addition to Snail, nuclear accumulation of β-catenin is a typical feature of tubular dedifferentiation [26]. As the phosphorylation and functional inactivation of GSK-3β results in the stabilization of cytoplasmic β-catenin and Snail [26], we measured the expression of Snail and β-catenin in our murine model of AKI-to-CKD progression and found it to be markedly increased in WT UIRI mice, but attenuated in Akt1−/− UIRI mice. Taken together, our study indicates that the attenuation of tubular dedifferentiation by genetic deletion of Akt1 is associated with decreased expression of p-GSK-3β, Snail, and β-catenin. Thus, these findings highlight the role of the Akt1/GSK-3β/(Snail and β-catenin) pathway in tubular dedifferentiation during AKI-to-CKD progression.

Akt isoforms have different functions and may induce different phenotypes in a cell- and disease-dependent manner [28,29]. For instance, Akt2 is essential for maintaining podocyte viability and function in a murine model of 75% nephron reduction [29]. Akt2 is also thought to be involved in renal fibrosis in a murine model of unilateral ureteral obstruction [17]. The present study demonstrates the involvement of Akt1 in tubular dedifferentiation and renal fibrosis in a murine model of UIRI without contralateral nephrectomy. It is unclear why the role of Akt isoforms varies depending on the renal fibrosis model. We believe that further studies are needed regarding renal fibrosis models other than UUO, 75% nephron reduction, and IRI, to elucidate the roles of Akt isoforms in the renal fibrosis.

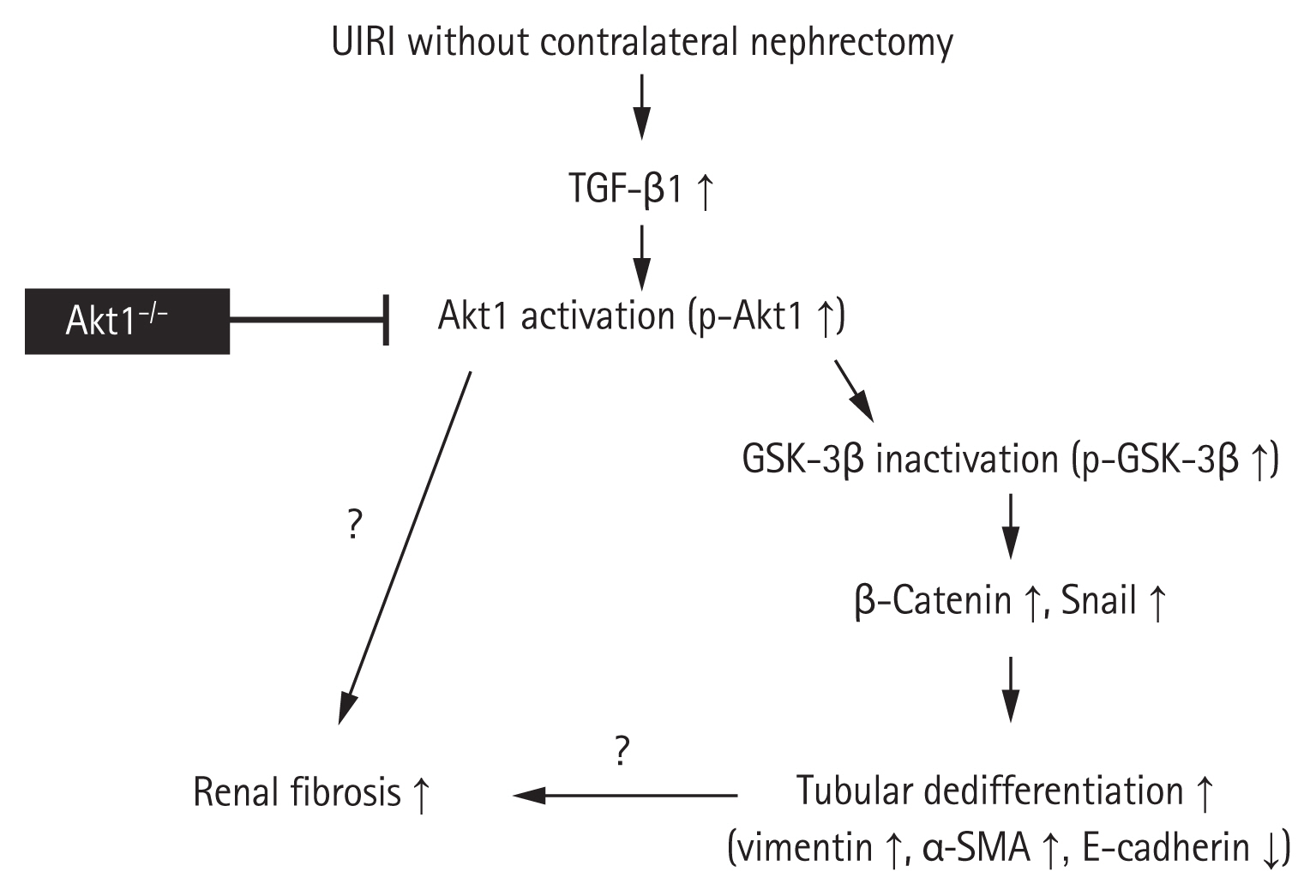

The conclusions of the present study are summarized in Fig. 6. We demonstrated that the genetic deletion of Akt1 results in the attenuation of tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation during AKI-to-CKD progression in a murine model of UIRI without contralateral nephrectomy. This effect was associated with a decrease in the levels of p-GSK-3β, Snail, and β-catenin, independent of the TGF-β1/Smad pathway. Thus, Akt1 could serve as a potential novel therapeutic target for inhibiting AKI-to-CKD progression. However, further studies are needed to determine, to what extent the tubular dedifferentiation by Akt1 contributes to renal fibrosis during AKI-to-CKD progression. Additional studies are also needed to determine if Akt1 plays roles other than tubular dedifferentiation in renal fibrosis.

Schematic illustration of the role of Akt1 in renal fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation during acute kidney injury (AKI)-to-chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression. Unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury (UIRI) without contralateral nephrectomy upregulates transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1). TGF-β1 upregulation induces Akt1 activation, which in turn inhibits glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) activation. Inactivated GSK-3β activates Snail and β-catenin for the regulation of proteins involved in tubular dedifferentiation, such as vimentin, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and E-cadherin. The genetic deletion of Akt1 results in the attenuation of tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation. However, future studies are needed to determine, to what extent the tubular dedifferentiation by Akt1 contributes to renal fibrosis during AKI-to-CKD progression. Additional studies are needed to verify if Akt1 plays any roles other than tubular dedifferentiation in renal fibrosis.

KEY MESSAGE

1. Akt1, not Akt2 or Akt3, was activated in a murine model of acute kidney injury (AKI)-to-chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression.

2. Genetic deletion of Akt1 was associated with attenuated tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation during AKI-to-CKD progression.

3. Attenuation of renal fibrosis and tubular dedifferentiation upon Akt1 deletion was independent of the transforming growth factor β1/Smad pathway, but was related to the glycogen synthase kinase-3β, Snail, and β-catenin pathways.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program, through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2017R1D1A1B03034926).