Pleural and pericardial empyema in a patient with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis peritonitis

Article information

To the Editor,

Pleural empyema is usually complicated with pneumonia but may develop from hematogenous spreading from an extrapulmonary focus [1]. We report a case with pleural and pericardial empyema with cardiac tamponade complicating continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) peritonitis.

A 47-year-old man with end-stage renal disease had been on CAPD for the previous 3 months. He was admitted with abdominal pain, turbid peritoneal dialysate f luid, and exertional dyspnea for 2 days. The total leukocyte count in the peritoneal fluid was 340/mm3 (neutrophil count 29%) and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) was identified from a culture of the peritoneal dialysate. MSSA was also identif ied in blood culture. He was diagnosed with CAPD peritonitis and treated with intraperitoneal cefazolin.

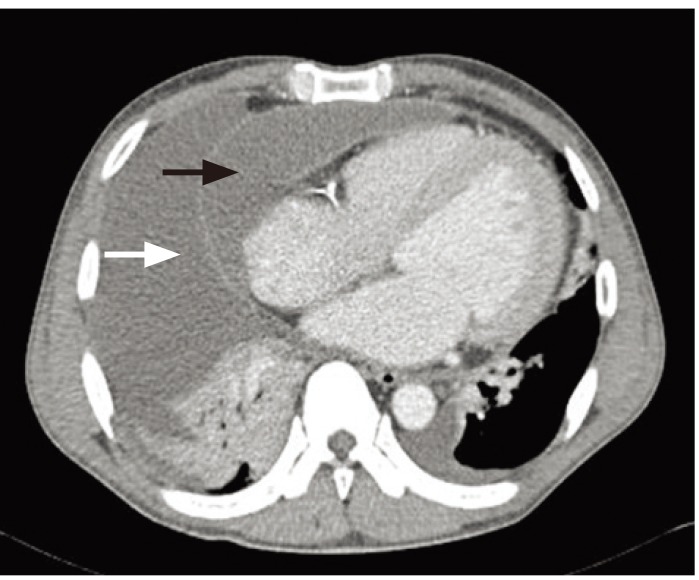

Simultaneously, a large amount of right pleural effusion was seen with cardiomegaly, but without pneumonic consolidation (Fig. 1). The pleural fluid proved to be exudate effusion and MSSA was identified from a culture. This empyema was treated with percutaneous drainage and antibiotics.

Chest computed tomography scan shows right pleural effusion (white arrow) and pericardial effusion (black arrow).

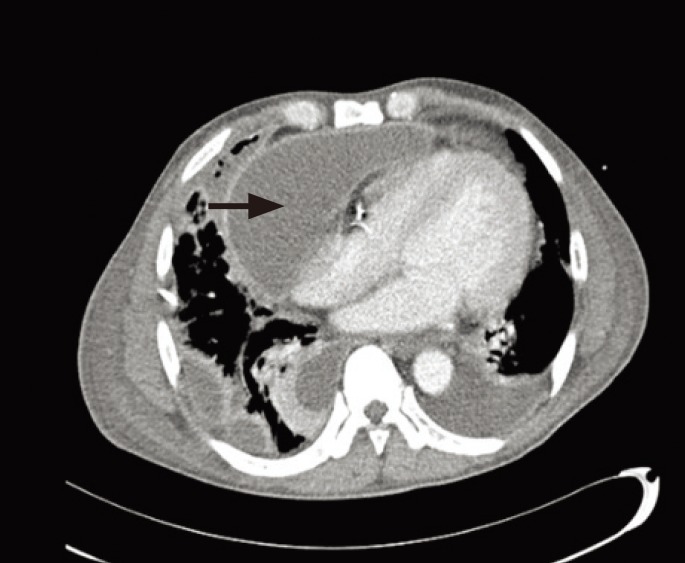

On the 8th day, his dyspnea worsened, accompanied by dizziness. His blood pressure dropped to 70/40 mmHg. Echocardiography and chest computed tomography showed markedly increased pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade (Fig. 2). Pericardiocentesis and a pericardial window operation were performed.

Chest computed tomography scan shows markedly increased pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade (arrow).

Two weeks later, the peritoneal f luid became clear and the leukocyte count in the dialysate fluid normalized. At 8 weeks after surgery, he was discharged with complete resolution of the pleural and pericardial empyema.

In this case, the pleural empyema was assumed to have developed from hematogenous spreading rather than pleuro-peritoneal communication, because the same microorganism (MSSA) was identified from the cultures of blood, peritoneal dialysate, and pleural fluid. The glucose level in pleural fluid is much less than that of peritoneal dialysate. Our case demonstrates that CAPD peritonitis can be an extrapulmonary cause of pleural empyema. Interestingly, pericardial empyema with cardiac tamponade was also a complication in our patient.

This case suggests that CAPD peritonitis can be a cause of pleural empyema and pericardial empyema, which may progress to cardiac tamponade.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.