Subacute thyroiditis presenting as acute psychosis: a case report and literature review

Article information

Abstract

We describe herein an unusual case of subacute thyroiditis presenting as acute psychosis. An 18-year-old male presented at the emergency department due to abnormal behavior, psychomotor agitation, sexual hyperactivity, and a paranoid mental state. Laboratory findings included an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 36 mm/hr (normal range, 0 to 9), free T4 of 100.0 pmol/L (normal range, 11.5 to 22.7), and thyroid stimulating hormone of 0.018 mU/L (normal range, 0.35 to 5.5). A technetium-99m pertechnetate scan revealed homogeneously reduced activity in the thyroid gland. These results were compatible with subacute thyroiditis, and symptomatic conservative management was initiated. The patient's behavioral abnormalities and painful neck swelling gradually resolved and his thyroid function steadily recovered. Although a primary psychotic disorder should be strongly considered in the differential diagnosis, patients with an abrupt and unusual onset of psychotic symptoms should be screened for thyroid abnormalities. Furthermore, transient thyroiditis should be considered a possible underlying etiology, along with primary hyperthyroidism.

INTRODUCTION

Triiodothyronine (T3) receptors are distributed throughout the brain, especially in the limbic system, and they seemingly support a variety of functions including emotion, behavior, and long term memory [1]. Evidence suggests that the modulation of the adrenergic receptor response to catecholamines by thyroid hormones in the central nervous system (CNS) may lead to psychotic behavior in thyrotoxic patients [2]. As a result, persons with thyroid dysfunction frequently experience a wide variety of neuropsychiatric sequelae. However, most medical texts do not mention psychosis as a presenting feature of thyrotoxicosis. Additionally, most cases of psychosis caused by thyrotoxicosis or hyperthyroidism have been described in patients with Graves' disease or toxic multinodular goiter. Herein, we report a case of an 18-year-old male with subacute thyroiditis who presented with acute psychosis.

CASE REPORT

An 18-year-old male presented to the emergency department due to abnormal behavior, agitation, and increased activity. One week prior to this visit, the patient had reported experiencing dizziness, headache, and sore throat, for which he had taken a cold medicine which had included a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Three days prior to the emergency department visit, the patient had reported experiencing anxiety, irritability, and restlessness, which subsequently worsened to additional features of psychomotor agitation and a paranoid mental state. The patient was healthy with the exception of these psychomotor problems; he reported doing well in school and maintained good interpersonal relationships. There was no history of recent or past alcohol or drug abuse and there was no family history of psychiatric disorders.

On arrival, the patient appeared agitated and had a poor attention span. He complained of a sore throat, febrile sensation, and dizziness. He was irritable and threatening, as well as talkative. His speech was irrational and seemingly random. The patient also exhibited persecutory delusions toward his mother. Physical examination revealed tachycardia with a heart rate over 100 beats/min, moist skin, and an elevated body temperature (37.8℃). Chest and abdominal examinations revealed no abnormalities.

Laboratory findings included a leukocyte count of 6.02 × 109/L, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 36 mm/hr (normal range, 0 to 9), aspartate aminotransferase of 38 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase of 62 IU/L, and high sensitive C-reactive protein of 0.21 mg/L (normal range, 0 to 5). Brain computed tomography and subsequent lumbar puncture revealed no abnormal findings. Thyroid function tests revealed a thyrotoxic state with free T4 of 100.0 pmol/L (normal range, 11.5 to 22.7) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) of 0.018 mU/L (normal range, 0.27 to 4.2), antithyroid peroxidase antibody and anti-TSH receptor antibody testing were negative. The patient's thyroid gland was hard and mildly enlarged, and he reported tenderness on palpation. Subacute thyroiditis was suspected, but the patient's uncooperative state prohibited further diagnostics. We subsequently consulted the psychiatry department. According to the clinical symptoms and laboratory results, a psychiatrist diagnosed the patient with a mood disorder due to a general medical condition (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition, 293.83), and the accompanying symptoms were presumed to be the result of a thyrotoxic state caused by subacute thyroiditis.

The patient was admitted to a closed ward in the psychiatric department for careful observation. Symptomatic treatment and heart rate control with a beta blocker (propranolol 20 mg twice daily), was continued, and antipsychotic drugs, including haloperidol 5 mg daily and lorazepam 4 mg daily, were also used. Over the first 3 days of admission, the patient's increased activity, especially sexual hyperactivity, and offensive attitude did not subside, but after 2 weeks, marked improvement was observed in all symptoms. Subsequent blood tests revealed improved thyroid function with a free T4 of 41.4 pmol/L, and TSH of 0.01 mU/L. The patient's overall condition was markedly better and he was more cooperative. Therefore, thyroid ultrasonography and a technetium-99m (99mTc) scan were performed. The sonographic findings included multifocal heterogeneous echogenicity with normal gland size and decreased vascularity (Fig. 1). The 99mTc pertechnetate scan revealed homogenously reduced Tc uptake in the thyroid gland (20 minutes Tc-pertechnetate uptake, 1.1%) (Fig. 2).

(A, B) Thyroid ultrasonography. Ultrasonography revealed multifocal heterogeneous lesions with normal gland size and decreased vascularity.

Technetium-99m (99mTc) pertechnetate thyroid scan. The 99mTc pertechnetate scan demonstrated homogenously reduced Tc uptake in the thyroid gland (20 minutes Tc-pertechnetate uptake, 1.1).

Approximately 20 days after hospitalization, the patient's free T4 level had decreased to nearly normal and he was gradually weaned off the antipsychotics before being subsequently discharged. On follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic and has since returned to school without recurrence of psychiatric symptoms (Fig. 3).

Clinical course of the patient during and after hospitalization. The appearance of psychiatric symptoms was chronologically related to the onset of thyrotoxicosis and the resolution of the psychosis was temporally related to the attainment of biochemical euthyroidism and amelioration of the tachycardia. HR, heart rate; fT4, free T4; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; HD, hospitalization day; OPD, outpatient department.

DISCUSSION

Subacute thyroiditis, a self-limiting inflammatory thyroid disorder usually caused by a viral infection, most often presents with thyroid pain and systemic symptoms. The clinical features include thyrotoxicosis, suppressed levels of TSH, decreased thyroid uptake of radioactive iodine, and an elevated ESR. Common symptoms of thyrotoxicosis include heat intolerance, excessive sweating, weight loss, palpitations, and gastrointestinal upset. Various psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, emotional lability, insomnia, agitation, mania, and depression are also concurrent with hypermetabolic symptoms. Nevertheless, psychosis and acute confusion are rare as an initial presentation.

There is little doubt that thyroid hormone plays a major role in the regulation of mood, cognition, and behavior. Indeed, persons with thyroid dysfunction frequently experience a wide variety of neuropsychiatric sequelae. However, the pathogenesis of psychosis in thyrotoxicosis is remains to be explained. The brain appears to possess a unique sensitivity to thyroid hormone and to utilize thyroid hormone differently from other organ systems [3]. High concentrations of T3 receptors are found in the limbic system (especially the amygdala and hippocampus), and seemingly support a variety of functions including emotion, behavior, and long-term memory. Another possible mechanism involves excess thyroid hormone affecting neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, or second messengers [4]. Evidence suggests that modulation of the beta-adrenergic receptor response to catecholamines by thyroid hormones may also contribute to these effects. Thyroid hormones increase the ability of these receptors to receive stimulation. Such interaction between catecholamines and thyroid hormones in the CNS is strengthened by their common origin from the amino acid tyrosine and their synergism in many metabolic processes [2].

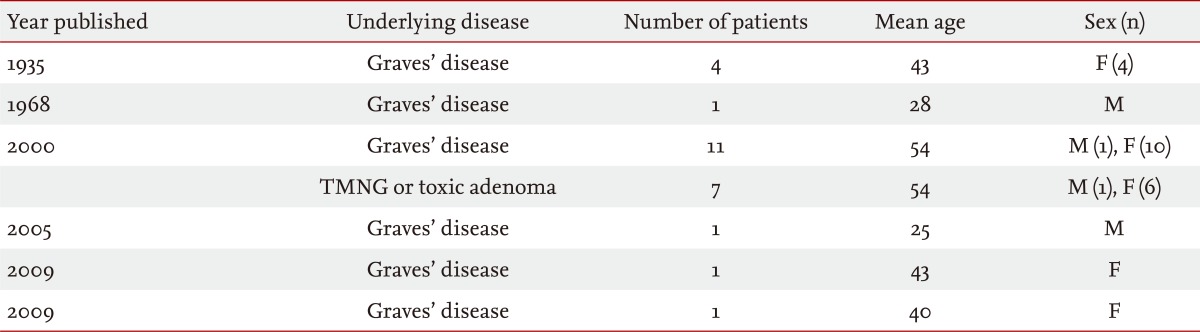

In 1835, in Graves' classic description of the disorder that now bears his name, he focused on nervous dysfunction, suggesting a relationship between the thyroid gland with the syndrome of globus hystericus [5]. In 1840, Basedow provided the first description of associated psychosis, but it was not until 1886 that a thyrotoxic syndrome of endocrine origin was clearly distinguished from a group of neuroses [6]. Brownlie et al. [7] reported a series of newly diagnosed thyrotoxic patients with concurrent acute psychosis which included 11 cases of Graves' disease, six cases of toxic multinodular goiter, and one case of toxic adenoma. They suggested that thyrotoxicosis is a precipitant of acute affective psychosis. Several additional cases of psychological illness associated with thyrotoxicosis have been reported since (Table 1). Furthermore, psychiatric disorders often accompany hypothyroidism. Psychosis associated with hypothyroidism, 'myxedema madness' is generally accepted as a real phenomenon. The occurrence of more severe psychiatric features depends upon the severity and duration of disease and the underlying predisposition of the individual to psychiatric instability.

Most cases of thyroid-related psychosis have been described in patients with Graves' disease or toxic multinodular goiter; however, thyrotoxicosis associated with transient thyroiditis or factitious thyrotoxicosis can also result in severe behavioral disturbances, including organic psychosis. Two cases of acute psychotic episodes in patients with thyrotoxicosis factitia and subacute thyroiditis have been reported [8,9]. In both cases, psychotic features occurred abruptly and resolved with resolution of the thyrotoxic state. Furthermore, the thyroidal inflammation characteristic of subacute thyroiditis, can cause schizophrenia, mania, psychotic depression, and paranoid behavior severe enough to require inpatient treatment.

While we considered that the coexistence of psychosis and subacute thyroiditis could have been a chance occurrence, we diagnosed our patient with psychosis due to subacute thyroiditis for three reasons. First, the appearance of psychiatric symptoms was chronologically related to the onset of thyrotoxicosis and the resolution of the psychosis was temporally related to the attainment of biochemical euthyroidism and amelioration of the tachycardia (Fig. 3). This suggested that the psychotic symptoms were directly related to the thyrotoxicosis. Second, the clinical symptoms of a sore throat and anterior neck tenderness, the laboratory results of an elevated ESR and an elevated free T4 level, and the typical findings on thyroid ultrasonography and scan were compatible with subacute thyroiditis. Third, there was no history of recent or past alcohol or drug abuse, and there was no family history of psychiatric disorders. Treatment with a β-adrenergic antagonist drug can be useful in controlling the anxiety associated with thyrotoxicosis in subacute thyroiditis. Furthermore, in acutely psychotic patients, dopamine blockade with a medicine such as haloperidol may be required to reduce excitement. As such, our patient was treated appropriately with propranolol, haloperidol, and lorazepam.

When dealing with such a case, it is important to make a precise diagnosis and exclude other possible diseases. Several medical conditions can cause mood disorders, including Cushing's syndrome, Addison's disease, thyroid abnormalities, diseases of the pancreas, rheumatoid arthritis, and infectious diseases such as mononucleosis and electrolyte disturbances. With the exception of thyrotoxicosis, our patient had no abnormal symptoms or laboratory results. It is also important to distinguish these cases from the hyperthyroxinemia that may accompany acute psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and mania. Free thyroxine elevation is modest and transient and is usually seen within 1 week. This entity has not been established clearly, but may be considered a form of nonthyroidal illness [10].

In conclusion, although a primary psychotic disorder should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients who present with an abrupt onset of unusual psychotic symptoms, in the absence of a history of substance abuse, such patients should be screened for thyroid abnormalities or other underlying endocrine abnormalities. In particular, the presence of physical manifestations such as heat intolerance, excessive sweating, weight loss, and palpitations should raise suspicion of hyperthyroidism. A high index of suspicion is often required to detect the association. Furthermore, in addition to primary hyperthyroidism, transient thyroiditis should also be considered a possible etiology.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.