Insulin Resistance as a Risk Factor for Gallbladder Stone Formation in Korean Postmenopausal Women

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

The objective of this study was to determine whether insulin resistance is associated with gallbladder stone formation in Korean women based on menopausal status.

Methods

The study included 4,125 consecutive Korean subjects (30-79 years of age). Subjects who had a medical history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, other cardiovascular disorders, or hormone replacement therapy were excluded. The women were subdivided into two groups according to their menopausal status.

Results

Analysis of premenopausal women showed no significant differences in the homeostasis model of assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index between the two groups in terms of gallstone disease. The associations between the occurrence of gallbladder stones and age, obesity, abdominal obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and high HOMA-IR index were statistically significant in the analysis with postmenopausal women. In a multiple logistic regression analysis, low high density lipoprotein-cholesterol was an independent predictor of gallbladder stone formation in premenopausal women. However, the multiple logistic regression analysis also showed that age and HOMA-IR were significantly associated with gallbladder stone formation in postmenopausal women. In an additional analysis stratified by obesity, insulin resistance was a significant risk factor for gallbladder stone formation only in the abdominally obese premenopausal group.

Conclusions

Insulin resistance may be associated with gallbladder stone formation in Korean postmenopausal women with abdominal obesity.

INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder (GB) stone disease is a common disorder affecting approximately 10-25% of the adult population in Western countries [1]. GB stone formation is multifactorial, and known risk factors are advancing age, female gender, genetics/ethnicity, obesity, rapid weight loss, diet, drugs, and activity [2]. The association of GB stone disease with metabolic abnormalities such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity, and hyperinsulinemia has supported the hypothesis that GB stone formation is a type of metabolic syndrome [3,4].

GB stone formation is more common in women than in men, and estrogen is considered to be the obvious reason for the gender difference. The liver has estrogen receptors, and the presence of endogenous estrogens causes cholesterol saturation in the bile, inhibition of chenodeoxycholic acid secretion, and an increase in cholic acid level [5]. Female predominance is obvious, particularly at a young age. However, the gender difference narrows with increasing age, particularly after menopause. Moreover, female predominance is less evident in Asia where the occurrence of pigmented stones is more common [2].

The epidemiological characteristics of GB stones differ between Asia and the west. Literature on GB stone composition in Korea shows that 30-40 years ago more than half of the GB stones were brown pigmented stones [6]. However, this pattern has changed rapidly, and a relative increase in the prevalence of cholesterol stones has been observed, in parallel with the changing economic status and diet in Korea [7-9].

Based on recent epidemiological data showing an increasing ratio of cholesterol stones in the Korean population, we hypothesized that insulin resistance plays a role in the development of GB stone formation depending on menopausal state. The objective of this study was to evaluate whether insulin resistance is associated with GB stone formation in non-diabetic Korean women based on menopausal status.

METHODS

Subjects

From January 2006 to December 2007, 5,592 women visited the Center for Health Promotion at Pusan National University Hospital for a comprehensive medical check-up. Of these, 4,125 women (30-79 years of age) were enrolled in this study, and 1,467 subjects were excluded based on the following criteria that might inf luence insulin resistance and GB disease: 1,183 had a medical history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, or hormone replacement therapy; 59 had a history of a cholecystectomy; 92 had ultrasonography (US) findings of a Clonorchis sinensis infection; 192 had US findings of other GB diseases, including GB poly and GB sludge; and eight had intrahepatic bile duct stones. The women were subdivided into two groups based on their responses to a questionnaire on their menopausal status (premenopausal state, n = 2,549; postmenopausal state, n = 1,576). This study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Hospital, and all subjects gave their informed consent to participate.

Measurements

The health information of the subjects included their medical history, a physical examination, responses to a health-related behavior questionnaire, and anthropometric measurements. Data on alcohol intake and smoking habits were obtained by interview. The questions on alcohol intake included items about the type of alcohol beverage, frequency of alcohol consumption on a weekly basis, and usual amount consumed daily. Weekly alcohol intake was calculated and then converted to daily alcohol consumption. Subjects were divided into two groups based on their alcohol consumption: non-drinkers, 0-180 g/wk; and drinkers, > 180 g/wk. Based on smoking status, they were classified as non-smokers or smokers (former or current). The subjects wore light clothing without shoes for the height and weight measurements. Body mass index was calculated as the weight (kg) divided by the height (m) squared. Waist circumference (WC) was measured at a level midline between the bottom of the rib cage and the top of the iliac crest with a soft tape around the body with the subjects standing. Blood pressure was measured on the right arm with subjects in a sitting position after a 5 minutes rest.

Laboratory methods

Blood samples were obtained from the antecubital vein and collected in evacuated plastic tubes after overnight fasting. The samples were subsequently analyzed at a certified laboratory at Pusan National University Hospital. The standard liver enzyme, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglyceride (TG) levels were measured with an enzymatic colorimetric method using a Hitachi 7600 Analyzer (Hitachi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). A Behring BN II Bephelometer (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany) was used to measure high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels. White blood cell counts were assessed with an autoanalyzer (XE-2100, Sysmex, Tokyo, Japan). Plasma free fatty acids were measured with an enzyme assay kit. Fasting plasma glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method using a Synchron LX 20 system (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Fasting insulin was determined by radioimmunoassay (Diagnostic Product Co., Los Angeles, CA, USA) using antibody-coated tubes. The mean intra- and inter-assay CVs were 4.2% and 6.3%, respectively. The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index was calculated using the following formula [10]:

HOMA-IR = [fasting serum insulin (µU/mL) × fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L)/22.5]

US imaging

We evaluated the presence of GB stones and fatty liver using abdominal US (HDI 5000, Philips, Bothell, WA, USA) performed by skilled radiologists. After an overnight fast, subjects were examined in the supine position, oblique position right side up, during the change from one position to another, and in a standing position. GB stones were detected by the presence of strong intraluminal, gravity-dependent echoes that produced acoustic shadowing. GB sludge was diagnosed as diffuse, low-amplitude echoes forming a fluid-fluid level. The sludge was characterized by homogeneous echoes or heterogeneous echoes of 2 to 5 mm with nonshadowing echogenic foci [11]. Three grades were defined for fatty liver infiltration of the liver: mild, in which there was a slight diffuse increase in the fine echoes in the hepatic parenchyma with normal visualization of the diaphragm and intrahepatic vessel borders; moderate, in which there was a moderate diffuse increase in the fine echoes with slightly impaired visualization of the diaphragm and intrahepatic vessels; and severe, in which there was a marked increase in the fine echoes with poor or no visualization of the diaphragm, intrahepatic vessels, and posterior portion of the right lobe of the liver [12]. Any degree of fatty infiltration including mild, moderate, and severe infiltrations, was considered a fatty liver.

Definition of metabolic syndrome

We used the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria for diagnosing metabolic syndrome [13]. These criteria recommend a lower WC cutoff for the Asian population than the Caucasian population because Asians are predisposed to metabolic abnormalities at a lower WC. Therefore, we defined central obesity as a WC of 85 cm in females, based on the recommendation of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity [14].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± SD. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies and proportions. An independent two-sample t test was used to compare two independent groups. Pearson's χ2 test was employed to analyze categorical data, as appropriate. Distributions of continuous variables were examined for skewness and kurtosis, and logarithm-transformed values of nonnormally distributed variables were used for comparison between the two groups. The odds ratios (Ors) of HOMA-IR were calculated with reference to the lowest quartile for continuous variables or the lowest category for categorical variables. Analyses were conducted after the subjects were stratified by obesity to identify the association between insulin resistance and GB stones based on obesity. Multivariate logistic analysis, using a backward procedure on the basis of likelihood ratios, was conducted to determine the independent risk factors for GB stones based on menopausal status. All p values are two-tailed, and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

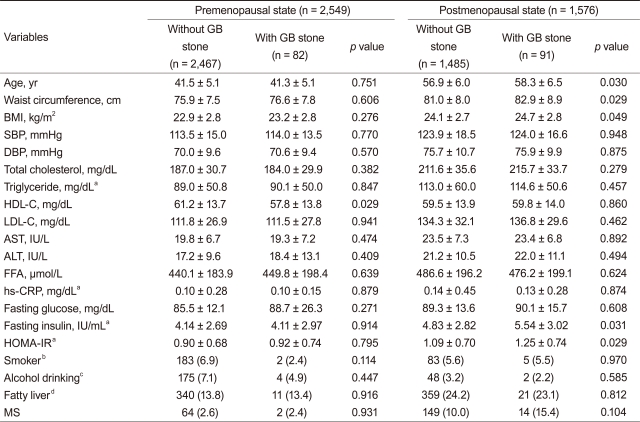

Of the 4,125 women examined, 173 (4.2%) had GB stones. In comparison with women without GB stones, those with GB stones were significantly older and had a higher WC, BMI, hs-CRP, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR. Moreover, women with GB stones had a significantly lower HDL-cholesterol level than those without GB stones (Table 1). Metabolic syndrome, as defined by IDF criteria, was more frequently observed in women with GB stones (9.2% vs. 5.4, p = 0.030).

As shown in Table 2, subjects were subdivided into two groups according to their menopausal status. Only the HDL-cholesterol level differed significantly between premenopausal women with and without GB stones. However, significant differences were observed for age, WC, BMI, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR among postmenopausal women with and without GB stones.

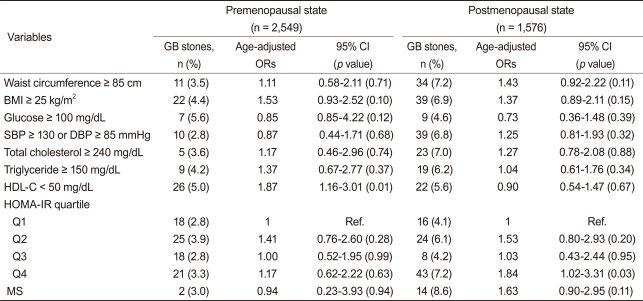

In age-adjusted logistic regression analyses, only low HDL-cholesterol was significantly associated with the risk of GB stone formation in premenopausal women (Table 3). Analysis of postmenopausal women revealed an increased risk of GB stone formation for those in the fourth quartile of HOMA-IR in comparison with those in the lowest quartiles (age-adjusted OR, 1.84; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02 to 3.31; p = 0.03).

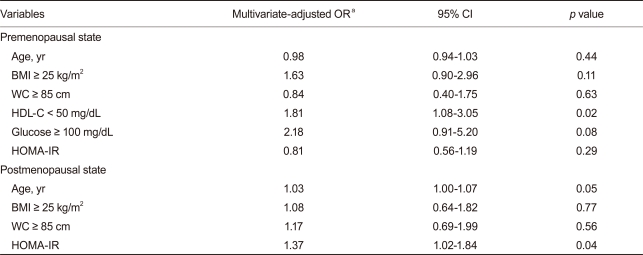

The multivariate logistic regression analysis for GB stone formation was adjusted for age, smoking habits, drinking habits, BMI, WC, glucose, lipid profiles, blood pressure and HOMA-IR as independent variables. In the multivariate model, only low HDL-cholesterol was significantly associated with GB stone formation in premenopausal women. However, age and HOMA-IR among postmenopausal women remained significantly associated with GB stone formation in this adjusted analysis (Table 4).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis with gallbladder stone formation as the dependent variable based on menopausal state

An additional analysis stratified by WC showed that HOMA-IR was significantly associated with an increased prevalence of GB stones only in the higher WC group in postmenopausal women (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.36; p =0.04). However, no significant association between HOMA-IR and the prevalence of GB stones was observed after the subjects were stratified by BMI (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to investigate the relationship between insulin resistance and GB stone formation in Korean women based on menopausal status. We found that different factors may serve to promote GB stone formation according to menopausal status in Korean women. Insulin resistance was associated with GB stone formation in Korean women after menopause, and this association was only observed in postmenopausal women who were centrally obese.

Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance are common factors linking cholesterol GB stones, diabetes, and obesity [15,16]. Insulin may increase GB stone formation through a mechanism in which insulin increases the activity of hydroxyl-3-methyglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase and stimulates bile acid-independent flow of bile into perfused rat liver [17,18]. Scragg et al. [19] first demonstrated that mean plasma insulin concentration is higher in both male and female patients with GB stone disease, regardless of their age and TG levels. In a large-scale study, the risk of GB disease increased with levels of fasting insulin in Western women but not in Western men [16]. Among nondiabetic women, the prevalence of clinical GB disease increased with increasing insulinemia in a large, population-based study [20]. However, this relationship was not significant after adjusting for potential confounders. All of these earlier studies examined Western populations. A recent report showed that insulin resistance was positively associated with the occurrence of GB stones in nondiabetic Korean men, regardless of obesity [21]. In the present study, we found that the risk of GB stone formation was higher in the highest quartile than in the lowest quartile of HOMA-IR in postmenopausal women. Moreover, insulin resistance was an independent risk factor in Korean postmenopausal women in a multivariate analysis.

Obesity is a well-established risk factor for GB stone formation because this condition increases hepatic secretion of cholesterol [2]. The risk is particularly high in women and increases linearly with increasing obesity [22]. Thus, gallstone disease is closely related to abdominal obesity [23]. In Western women, the abdominal circumference and waist-to-hip ratio are associated with an increased risk of cholecystectomy, independent of BMI [23]. WC is a better indicator of abdominal fat than BMI and has proven to be rather predictive for metabolic complications. In this study, insulin resistance was significantly associated with GB stone formation in the abdominally obese group (WC > 85 cm) of postmenopausal women. This relationship between insulin resistance and GB stone formation was absent in the BMI-defined obese group, emphasizing the importance of abdominal obesity in GB stone formation.

Estrogen is the main factor responsible for the difference between males and females in terms of GB stone formation. One study showed that exogenous estrogens, administered either transdermally or orally, affect physiological markers in a pattern that favors GB stone formation [24]. The use of low-dose oral contraceptives has a relatively weak effect that may decrease with time [25]. An increased risk of GB stone formation was observed in clinical trials of postmenopausal women who underwent estrogen therapy [26,27]. In the present study, insulin resistance was not regarded as a main risk factor for GB stone formation in premenopausal women, because endogenous estrogen mainly affects GB stone formation. However, insulin resistance was one of the main factors for GB stone formation in postmenopausal women in whom the endogenous estrogen effect would be absent.

Although GB stones predominantly consist of cholesterol in Western subjects, no conclusive evidence links dyslipidemia and GB stones [28]. The low density lipoprotein cholesterol level has a weak correlation with GB stone formation, and low HDL cholesterol and high TG levels are positively associated with GB stones [29]. Analysis of premenopausal women in our study revealed that HDL-cholesterol level was significantly lower in subjects with GB stones; however, we did not find any component of dyslipidemia related to metabolic syndrome that could be correlated with GB stone formation in either premenopausal or postmenopausal women.

This study had certain limitations. First, no information was available on family history and history of parity. Parity is a significant risk factor for GB stone formation, and pregnancy is a high-risk period for GB stone formation [30,31]. Second, we were unable to identify the exact types of GB stones present. Pigmented stones may still be a significant component of GB stones in relatively older subjects, although a relative increase in the prevalence of cholesterol stones was recently reported in Korea. Moreover, we excluded subjects with several confounders such as those with C. sinensis infections, intrahepatic duct stones, and a previous history of a cholecystectomy. It may be necessary to distinguish the exact types of GB stones and to determine the role of insulin resistance in GB stone formation, because the relationship between insulin resistance and pigmented stone formation remains unknown.

In conclusion, insulin resistance may be associated with GB stone formation in Korean postmenopausal women, in parallel with the changing economic status and diet in Korea. Thus, insulin resistance may represent a causal link between central obesity and GB stone formation in Korean postmenopausal women.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a clinical research grant from Pusan National University Hospital (2010).

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.