Solitary Intra-abdominal Tuberculous Lymphadenopathy Mimicking Duodenal GIST

Article information

Abstract

Tuberculosis remains prevalent in developing countries and has recently re-emerged in the Western world. Intra-abdominal tuberculosis can mimic a variety of other abdominal disorders, and here we describe a patient with solitary tuberculous mesenteric lymphadenopathy mimicking duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). A 22-year-old woman complained of epigastric discomfort and was presumed to have a duodenal GIST after an endoscopic examination and abdominal CT scan. However, exploratory laparotomy revealed an enlarged node penetrating the duodenal bulb, which was diagnosed histopathologically as tuberculous lymphadenitis. This case suggests that in regions with a high prevalence of tuberculosis, intra-abdominal tuberculosis is often mistaken as a malignant neoplasm. A high index of suspicion and the accurate nonsurgical diagnosis of intra-abdominal tuberculosis continues to be a challenge.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis persists as a common illness in developing countries, and western countries are experiencing a resurgence due to rising numbers of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome1, 2). Intra-abdominal tuberculosis, including peritonitis, enterocolitis, and mesenteric lymphadenitis, is relatively rare among extra-intestinal tuberculosis, although it is of considerable clinical importance3-6). In Korea, although the exact incidence of intra-abdominal tuberculosis is unknown, tuberculous enterocolitis has been reported to account for 4.8% of all tuberculosis, and therefore, intra-abdominal tuberculosis is clinically relevant in Korea. Intra-abdominal tuberculosis can present atypical clinicopathological features, which can make a proper diagnosis difficult8-10). We present here an unusual case of solitary intra-abdominal tuberculous lymphadenopathy mimicking duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

CASE REPORT

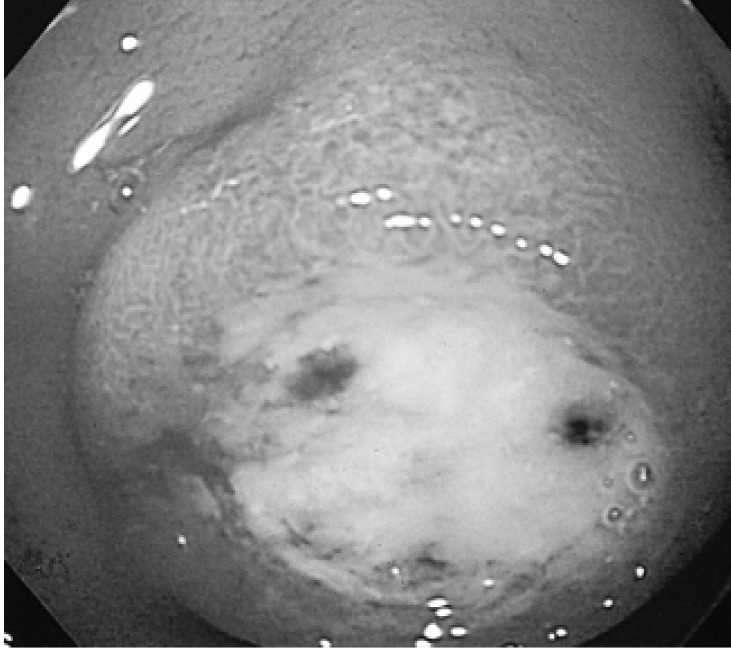

A 22-year-old woman presented with epigastric discomfort and intermittent dark-colored stools of two months duration. She had no previous illness and denied constitutional symptoms such as fever, weight loss, or night sweating. A physical examination detected no abdominal mass or tenderness, and no rebound tenderness. Laboratory studies showed a hemoglobin of 13.9 g/dL, leukocytes of 7,580/mm3, and an ESR of 17 mm/hr. Other biochemical tests results were within normal ranges, and anti-HIV Ab was negative. Stool occult blood was also negative. An esophagogastroduodenoscopic (EGD) examination revealed a round mass of about 3-cm at the duodenal bulb, with normal surrounding mucosa and central ulceration (Figure 1). Several red or black spots on the base of the ulceration evidenced recent bleeding. An endoscopic biopsy taken at the ulceration margin identified chronic duodenitis.

An esophagogastroduodenoscopic (EGD) examination revealed a round mass with normal surrounding mucosa and central ulceration in the duodenal bulb.

Chest X-ray films showed inactive pulmonary tuberculosis at the left upper lobe, and abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a well-defined round mass that enhanced as gastric mucosa, at the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb suggestive of duodenal GIST (Figure 2). Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) showed an ulcerative hypoechogenic mass at the submucosal layer of the duodenal bulb (Figure 3).

Abdominal CT scan showing an exophytic well-defined round mass in the duodenal bulb. The mass enhanced as gastric mucosa and was presumed to be a duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) showed an ulcerative hypoechogenic mass originating from the submucosal layer.

Exploratory laparotomy was performed to exclude the possibility of malignant GIST of the duodenum. During laparotomy, a solitary mass was detected around the hepatic artery, which penetrated the duodenal bulb. The mass was excised and a histopathological analysis revealed lymphadenopathy with caseous granuloma (Figure 4). Polymerase chain reaction of DNA extracted from the node was positive for tuberculosis and acid-fast bacilli were found by Ziehl-Neelsen tissue staining. The patient was diagnosed with solitary tuberculous lymphadenopathy and discharged on anti-tuberculosis medication. No evidence of recurrence has been observed during nine months of treatment.

DISCUSSION

Abdominal mesenteric lymphadenopathy is a relatively common manifestation of intra-abdominal tuberculosis, which occurs as a regional component of primary or secondary disease. Involved mesenteric nodes may form independent masses or they may adhere to adjacent structures. Tuberculosis usually affects multiple lymph node groups simultaneously, though isolated retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy is uncommon11, 12). Most tuberculous lymphadenopathies are visualized by abdominal CT as enlarged nodes with hypodense centers and peripherally hyperdense enhancing rims11) as conglomerate mixed density nodal masses, or as enlarged masses with homogeneous density12).

In the present case, an exophytic oval mass was noted on an abdominal CT scan on the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb. Moreover, it presented as a submucosal mass with central ulceration and suspected bleeding foci on EGD examination. Most cases of abdominal tuberculosis are complications of pulmonary tuberculosis, and thus in this patient with evidence of inactive pulmonary tuberculosis, a diagnosis of solitary mesenteric tuberculous lymphadenopathy with penetration into the duodenal wall appeared unlikely, and therefore, we suspected that the lesion was a duodenal GIST.

GIST is a rare neoplasm marked by mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. GISTs are generally located in the stomach; only 4% of cases are reported in the duodenum. However, despite their relative infrequency small bowel GISTs frequently manifest as gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal pain, or as a palpable mass13, 14), and can display unpredictable malignant behavior notwithstanding their small size. Duodenal GISTs can thus have a poorer prognosis than GISTs of the stomach15, 16). Because it is difficult to rule out duodenal GIST and because of the likelihood of bleeding or malignancy, we decided to excise the lesion for proper diagnosis and management. Laparotomy revealed a solitary mesenteric lymphadenopathy penetrating the duodenal bulb, and histopathologic analysis revealed it to be a tuberculous lymphadenopathy.

EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) has recently emerged as an important modality for diagnosing GIST17). Moreover, ultrasound-guided FNA offers a safe method for obtaining proof of tuberculosis in patients with suspected intra-abdominal tuberculosis18, 19). It is regrettable that we did not perform FNA prior to laparotomy in the present case.

The preferred treatment of intra-abdominal tuberculosis is anti-tuberculous medication; surgical management is normally reserved for complications or diagnostic uncertainty.

In conclusion, intra-abdominal tuberculosis can present a variety of conditions and in areas with a high prevalence the possibility of tuberculosis must be considered. Tuberculosis is curable when a diagnosis is made sufficiently early and appropriate treatment is started.

Notes

This study was supported by Inje University research funds (2002).