A Case of Primary T-Cell Lymphoma of the Duodenum

Article information

Abstract

Primary malignant lymphoma located in the duodenum is a rarity. A case of primary lymphoma of the duodenum in a 27-year-old man, in which the 2 discrete masses of duodenal bulb and the second portion with pancreatic head invasion was found, is reported here. Immunohistochemical evaluation of the present case showed that lymphoma cells expressed the T-cell markers MT1 and UCHL1. Treatment consisted of pancreaticoduodenectomy followed by antineoplastic chemotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

Primary gastrointestinal lymphomas are the most frequent among extranodal lymphomas1–4) but the lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract are rare and constitute only 4.5% of all lymphomas5) and 1% of all gastrointestinal neoplasms6). The incidence of lymphoma in the segments of the small intestine directly correlates with the amount of lymphoid tissue present;7) most lymphomas occur in the ileocecal region, while the duodenum remains as the most infrequent site8). Only sporadic cases of duodenal lymphoma have been reported in the literature since Alexander’s first case in 18779). Recently it has been possible to immunologically subclassify gastrointestinal lymphomas, and this demonstrated B-lymphocyte characteristics in at least 50% of gastrointestinal lymphomas4,10). Only rare reports document involvement of the gastrointestinal tract by T-cell lymphoma, and in most of these patients the intestinal involvement is a manifestation of widespread T-cell lymphoma arising in either the skin or lymph node11–13). We report the clinical, immunologic, and pathologic findings of a patinet who had T-cell lymphoma of the duodenum.

CASE REPORT

A 27-year-old man was admitted on June 15, 1990 with a 2-month history of upper abdominal pain and vomiting. He reported a 3 kg weight loss and past medical history was noncontributory. On physical examination the patient was anemic with a blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg. The abdomen was soft, without distension, palpable masses or hepatosplenomegaly. No lymphnodes were found in the neck, axilla or groins. Laboratory studies included hemoglobin 10.6 g/dl, WBC 5200/mm3 with 65% neutrophils and 28% lymphocytes, alkaline phosphatase 151 IU, ALT 56 IU, AST 60 IU, total bilirubin 3.9mg/dl, direct bilirubin 2.5mg/dl, amylase 69 U, and glucose 173mg/dl. A chest x-ray was normal. A gastrofiberscopic examination revealed extrinsic compression at the antrum, and an ulcerating mass with an elevated margin was found along the posterior wall, the greater curvature side of the duodenal bulb and the second portion of the duodenum (Fig. 1, 2).

Hypotonic duodenography showed an encircling filling defect from the gastroduodenal junction to the upper border of the ampulla of Vater (Fig. 3). A CT scan of the duodenum revealed a dilatation of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic duct and an enlargement of the pancreas head portion with a loss of fat plane between the duodenal second loop and pancreas mass lesion (Fig. 4). A microscopic examination of the gastrofiberscopic biopsy specimen disclosed malignant lymphoma of mixed small and large cell type, and Whipple’s operation was done. The first portion of the duodenum showed a fungating mass with raised margin and central ulceration, measuring 6×5 cm, located just distal to the gastroduodenal junction, and another separate tumor was seen at the duodenal second portion.

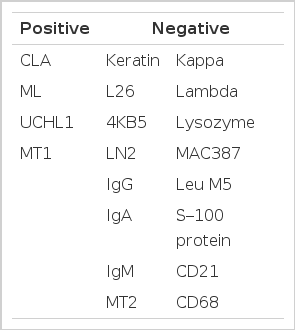

The seeond tumorous lesion revealed on irregular thickening of the mucosal fold and slightly polypoid shape (Fig. 5). Microscopic examination showed the diffuse infiltration of small cells with vague nodularity. These infiltrated cells were plasmacytoid in shape, with round nuclei and coarsely stippled chromatin (Fig. 6). Immunohistochemical staining showed strong positivity in the tumor cell with T cell marker MT1 (Fig. 7) and UCHL1 and showed negative results with B cell marker L26 and histiocytic marker CD68. Table 1 shows the results of the immunohistochemical staining. Tumor ploidy was determined by flow cytometry, and it was diploid with aws phase percentage of 36.83%, which was compatible with a malignant lymphoma of intermediate grade (Fig. 8).

Two discrete masses are noted. The first portion of the duodenum shows a fungating mass with raised margin and central ulceration, and the second tumorous lesion reveals an irregular thickening of the mucosal fold and slightly polypoid shape.

DISCUSSION

Only 1 to 2% of all primary gastrointestinal malignancies arise in the small bowel, despite its great length14–16). These tumors occur with increasing frequency in the distal small bowel, and the duodenum is the least common site of occurrence of the tumor17–18).

Adonocarcinoma is the most common type of small-bowel cancer, constituting 32 to 54% of all malignant enteric tumors;16,19) lymphoma is the next most frequent. So, rare case reports of duodenal lymphoma are published in the literature20–23).

The cause of lymphoma of the duodenum remains unclear. Lymphomas have been noted to occur with increasing frequency in patients with an adult celiac disease, nontropical sprue, steatorrhea of many years’ duration Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Sjogren’s syndrome, and other conditions24–26) but the rarity of the disease has precluded the precise identification of such factors.

The peak incidence of lymphoma of the duodenum occurs in the fifth decade with an average age of 40.5 years23), but there was a wide distribution from the first to the eighth decade. Of the 55 cases of lymphoma of the duodenum, 36 cases occurred in men for a male-to-female ratio of nearly 2:123).

Because tumors of the small intestine do not produce a characteristic clinical syndrome21), early clinical recognition of primary malignant lymphoma of the duodenum is difficult, and the diagnosis has been often delayed to such an extent that the disease has disseminated22).

The type and character of the symptoms are varied and appear to be dependent on the location of the lesion, the rapidity of growth, the degree of intestinal obstruction, and other complications caused by it21). Symptom clanacteristics can be largely divided into 4 main groups27). Those few causing obstruction result in early satiety, vomiting, and postprandial pain. Ulcerating lesions may result in bleeding, melena, anemia, and hematemesis. Penetrating lesions that involve the surrounding tissue can produce typical peptic ulcer symptoms. Jaundice may be seen in lesions that involve the periampullary region. Weight loss is often due to the cachexia of a widespread malignant disease. In cases of duodenal lesions, the abdominal findings are not constant. Diffuse or localized tenderness is usually present. A mass is rarely felt. Abdominal distension in varying degrees may be noted. There is usually little, if any, rigidity21).

The diagnosis of lymphoma of the duodenum largely depends on radiological studies and fiberoptic gastroduodenoscopic examinations, but the radiographic signs reported with lymphoma of the duodenum are varied and are, for the most part, nonspecific. Deformities of the duodenum are often thought to be secondary to peptic ulceration or diverticulum. The presence of mucosal thickening, irregular polypoid filling defects that may narrow the lumen, and rigidity of the duodenal wall should lead to a suspicion of duodenal lesions other than ulcer20). Until the fiberoptic gastroduodenoscope was developed, radiological studies were the primary procedures employed to diagnose neoplastic lesions of the duodenum. But there were many errors in patients examined by standard gastrointestinal X-rays20), and with the ever widening use of the endoscope, a new dimension has been added to the investigation. Today, fiberoptic gastroduodenoscopy is a safe and reliable method of distinguising between benign and malignant lesions by means of biopsy or surface brushings. Because of the rarity of lymphoma of the duodenum and of the late introduction of endoscopy, specific findings of lymphoma of the duodenum have not been reported. Usually a large ulcer with multiple involvement may suggest lymphoma of the duodenum.

A number of workers have attempted to determine the relative incidence of the different forms of intestinal lymphoma4,8), and the classification of primary malignant lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract by the origin of their cells has been performed by various immunohistochemical markers for histiocytic and B-cell tumors were employed, small intestinal lymphomas were found predominantly to be of B-cell tumors were employed, small intestinal lymphomas were found predominantly to be of B-cell type28–29). Recently, with the advance of immunohistochemical studies, a few cases of T-cell malignant lymphoma of the small bowel have been presented30–31), but primary T-cell malignant lymphoma of the small bowel is rare31) and some of them were associated with the celiac disease30).

The immunohistochemical evaluation of the present case showed that lymphoma cells expressed the T-cell markers MT1 and UCHL1, and these data were compatible with T-cell malignant lymphoma of the duodenum.

The successful treatment of primary lymphoma of the intestine depends on early diagnosis and the institution of promet treatment21). Definite treatment is directed toward the complete surgical removal of the lesion, and irradiation has been recommended for lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract by various authors as a palliative measure in those cases where definitive surgery cannot be accomplished or when the surgical margins or regional lymph nodes are involved by the tumor32–33). Unfortunately, the results of treatment of lymphoma of the duodenum have been uniformly poor. In the case of lymphoma of the duodenum, because of its anatomic relationship to the surrounding organs and the retroperitoneal nodes, apparently it has been possible only rarely to resect the diseased bowel in this area before it has extended into the contiguous organs or tissue21). So, surgical removal is possible only in a minority of cases, and the longent survivors have been treated by a palliative surgical procedure or biopsy alone, followed by radiotherapy23).

Since 1970, increasingly effective chemotherapy using multiple drug combinations has also become available for the treatment of gastrointestinal lymphoma, and the management of gastrointestinal lymphoma has evolved into an era of multimodality therapy using surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy34). We performed a pancreatico-duodenectomy followed by chemotherapy of COP BLAM III schedule in the present case.

The prognosis of duodenal lymphoma is poorer than that of lymphomas in other parts of the small intestine. There were 27 cases where the treatment modality and survival periods were reported and only 11 of the 27 patients lived 2 years, for a 2-year survival rate of 41%23). But a number of developments in the methods of early diagnosis and multimodality therapy will change the results of the management of duodenal lymphoma.

The patient presented is now 6 months postsugery and is doing well with chemotherapy.