Endoscopic Injection Sclerotherapy in Patients With Bleeding Esophageal Varices: A Retrospective Analysis

Article information

Abstract

Endoscopic injection sclerotherapy has been accepted as the procedure of choice for patients with variceal hemorrhage. To evaluate the efficiency of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in patients with bleeding esophageal varices, we did a retrospective study of 52 patients (non-sclerotherapy group) with bleeding esophageal varices who were admitted to hospitals and did not receive sclerotherapy and of 50 patients (sclerotherapy group) who received sclerotherapy with ethanolamine oleate. The mortality (sclerotherapy group vs. non-sclerotherapy group: 18:0% vs. 32.7%) during index hospitalization, the bleeding risk factor (the number of rebleeds per patient/month; 1.56±2.76 vs. 4.96±9.99: mean±SEM) and the mortality due to bleeding (14.0% vs. 36.5%) were higher in the non-sclerotherapy group than in the sclerotherapy group. Only those in Child’s class C who received sclerotherapy had a significantly better survival rate than the non-sclerotherapy group (p<0.05). Although formal comparisons were not made because of the retrospective nature of this study, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy is effective and appears to be superior to conventional medical treatments.

INTRODUCTION

When patients with cirrhosis of the liver start to bleed from ruptured esophageal varices, they stand a 40 percent chance of dying from the initial bleeding episode1–4). There are several methode of treating bleeding esophageal varices, including vasopresin administration, esophageal tamponade and operation. However, such medical and surgical treatments do not substantially prolong survival5). Many authors have reported endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy, a procedure first introduced in 19396), as a method to control acute variceal bleeding and to reduce the frequency of rebleeding. In several controlled trials, this treatment seemed to reduce bleeding rates7–11) and to decrease mortality11). However, this conclusion has recently been challenged12).

To evaluate the efficacy of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in patients with esophageal varices, we divided 102 patients admitted due to bleeding esophageal varices into a sclerotherapy group (those who had under gone sclerotherapy; 50 patients) and a non-sclerotherapy group (those treated by conventional methods; 52 patients). We then compared the control rate of acute bleeding and the frequency of rebleeding between the two groups retrospectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

In this study, we identified all the patients who were admitted to hospitals due to bleeding esophageal varices during the interval between December 1, 1984 and April 30, 1987. This period was selected because we began endoscopic injection sclerotherapy on December 1, 1984.

Of the 102 patients with bleeding esophageal varices, 50 underwent sclerotherapy (sclerotherapy group) and 52 were treated by conventional methods (systemic Pitressin and balloon tamponade) without receiving sclerotherapy (non-sclerotherapy group). Patients in both groups were initally resuscitated. If the bleeding stopped, patients were prepared by measures to improve coagulation, anemia, nutrition and ascites for later elective treatment during the same admission.

2. Methods

1) Technique of Injection Sclerotherapy

The procedure was done in the endoscopy room as electively as possible. If it had to be done urgently, endoscopy was preceded by gastric lavage. With the help of an oblique viewing fiberoptic endoscope (Olympus GIF-K2 and GIF-K10) and a flexible shielded injection needle, each varix was injected in turn with 2 to 5 ml of 5% ethanolamine oleate, and 5 to 15 ml of sclerosant per procedure was injected at a level of about 2–3 cm above the esophagogastric junction. When varices were actually bleeding, they were injected below the bleeding point. Care was taken to ensure intravariceal, not intramural, injection. Repeated injection of varices was performed at one-week intervals during admission and at two-to three-week intervals on an out-patient basis until the varix was completely obliterated.

2) Follow-up

Death certificates were obtained for all deceased patients. In addition, at the time of the most recent accrual of data, all living patients in both groups were contacted by letter or telephone to verify survival and the frequency of rebleeding episodes.

RESULTS

1. Characteristics of Patients

The underlying liver disease of most patients was liver cirrhosis in both groups. The sex and age distributions were similar in both groups. There were no significant differences in laboratory findings (hemoglobin, hematocrit, prothrombin time, total bilirubin and albumin), distribution of patients by Child’s classification and the degree of varices. Sclerotherapy was performed for 2.28±1.85 sessions per patient (mean±SEM, range: 1–11), and the follow-up periods were also similar among the patients in the two groups (Table 1).

2. Clinical Courses

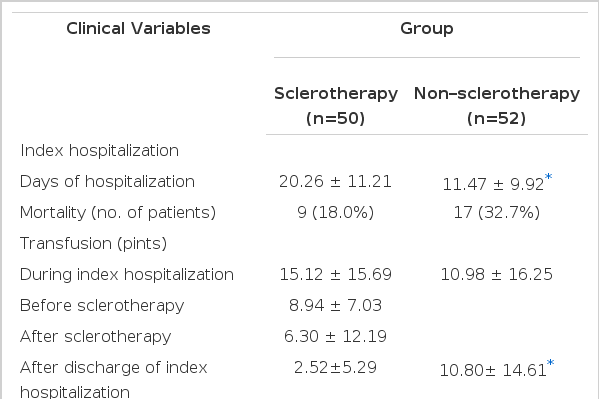

There was a significant difference (p<0.05) in the admission days of index hospitalization between the sclerotherapy (20.6±11.21 days) and the non-sclerotherapy (11.47±9.92 days) groups. However, the mortality during index hospitalization was 26.0 percent in the sclerotherapy (n=50) and 32.7 percent in the non-sclerotherapy (n=52) group.

The number of transfusions (pints) (mean±SEM) during index hospitalization was larger in the sclerotherapy group (15.12±15.69) than in the non-sclerotherapy group (10.98±16.25); however, after discharge of index hospitalization, it was larger in the non-sclerotherapy group (10.80±14.61) than in the sclerotherapy group (2.52±5.29). There were no significant statistical differences in the variables (mean±SEM) related to rebleeding between the two groups (sclerotherapy vs. non-sclerotherapy), such as the number of patients with rebleeding (52 percent vs. 82 percent), the total number of rebleeds (95 vs. 117), the number of rebleeds per patient (1.90±1.59 vs. 2.25±1.57) and the bleeding risk factor (number of rebleeds per patient/month) (1.56±2.76 vs. 4.96±9.99). However, a tendency appeared that showed all of the above variables as greater in the non-sclerotherapy group than in the sclerotherapy group. The control rate of bleeding was higher in the sclerotherapy group (79.8 percent) than in the non-sclerotherapy group (51.0 percent).

A tendency also existed showing a larger number of rehospitalized patients (sclerotherapy vs. non-sclerotherapy: 32 percent vs. 46 percent) and more day (mean±SEM) of rehospitalization for rebleeding after discharge (8.32±10.40 vs. 13.16±19.83) in the non-sclerotherapy group than in the sclerotherapy group (Table 2).

3. Complications of Endoscopic Injection Sclerotherapy

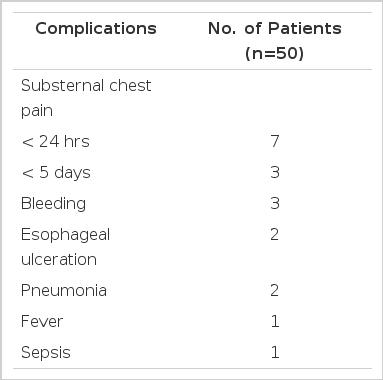

There were 114 courses of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy performed in 50 patients. There were 19 complications (16.7%) in 19 patients, such as substernal pain (10 patients), bleeding (three patients), esophageal ulceration (two patients), pneumonia (two patients), fever (one patients) and sepsis (one patients) (Table 3).

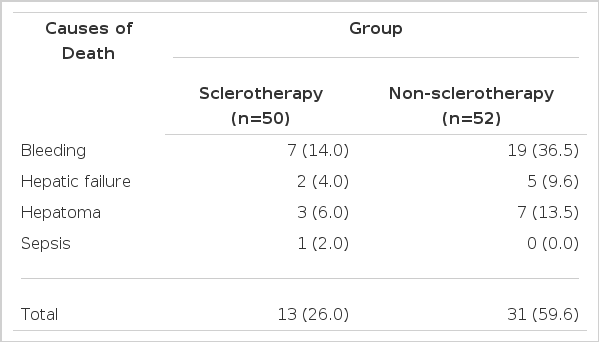

The causes of death during the observation period were bleeding in 26 patients (sclerotherapy vs. non-sclerotherapy; seven vs. 19), hepatic failure in seven patients (two vs. five), hepatoma in 10 patients (three vs. seven) and sepsis in one patient (sclerotherapy). The death rate due to bleeding was higher in the non-sclerotherapy groups (36.5 percent) than the sclerotherapy group (14.0 percent) (Table 4).

4. Survival Analysis

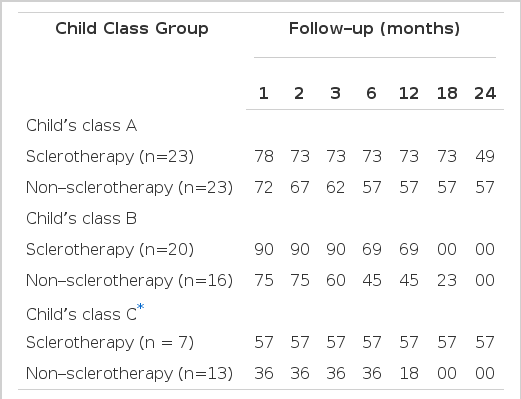

When patients who had dropped out were excluded, the survival rate was found to be better in the sclerotherapy group than in the non-sclerotherapy group (p<0.05) (Fig. 1). When patients were classified according to their status of hepatic function (Child’s class group A, B or C), only those in Group C who received sclerotherapy had significantly better survival than the non-sclerotherapy group (p<0.05) (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Fiberoptic endoscopic injection sclerotherapy is safe, does not require general anesthesia and can be performed on an out-patient basis in most patients during long-term management. Rigid endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (RIS) should be reserved for the difficult recurrent acute bleeder, where general anesthesia may provide safety and more effective sclerotherapy. In experienced hands, however, RIS is still a useful method in the small group of patients who develop recurrent bleeding on removal of the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, and where injection is difficult without compression in the presence of active bleeding13). In this study, we performed sclerotherapy using a fiberoptic endoscope.

Endoscopic sclerotherapy can be performed in three different way: (1) injection into the varices to thrombose, obliterate and eradicate them; (2) paravariceal injection to cover the varices with a fibrous layer; and (3) the combination of submucosal and intravariceal injection14). The paravariceal technique seems to be superior to the intravariceal method with regard to recurrence of hemorrhage and long-term results15). However, Rose and his colleagues16) have shown that intravariceal injection produces more rapid obliteration of varices than the paravariceal route.

Although intravariceal injection is followed by only a transient exposure of the endothelium to sclerosant, it is, nevertheless, effective16). Animal work suggests that one second suffices to produce irreversible maceration17) and thrombosis18). Because the sclerosants used are detergents, they act as weting agents and have surfactant properties even when considerably diluted19). A slow, steady injection over a period of 10 to 15 seconds may be effective without concomitant compression20).

Caudal clearing of intravariceally injected sclerosant into gastric varices has been demonstrated using radiographic contrast material21). Also, retrograde thrombosis of gastric varices occurring after injection of esophageal varices has been documented22). Intravariceal contrast was rapidly cleared upwards, wheres paravariceal contrast formed a round opacity alongside the vein that persisted for approximately 90 minutes and was responsible for the complication of esophageal ulceration and stenosis16). In this study, sclerotherapy was performed by the intravariceal method.

To be useful in clinical sclerotherapy, an ideal sclerosing agent must have a high sclerosis rate and low incidence of esophageal damage. These two properties must be balanced and then weighed along with availability, cost and ease of administration23).

Jensen24) compared several agents, including 5% sodium morrhuate, 5% ethanolamine, 1.5% sodium tetradecyl and 50% dextrose, in a canine model of portal hypertension. He concluded that sodium tetradecyl and ethanolamine oleate were the most efficacious single agents for sclerosis, although the former was associated with a 40% incidence of ulceration. A combination of 0.75% sodium tetradecyl and 47% ethanol was as effective as 1.5% tetradecyl alone in producing sclerosis but was not associated with mucosal ulceration. On the basis of the study, Jensen recommended this low concentration of sclerosants as the optimum injectate for sclerotherapy. Ethanolamine oleate has remained popular in Great Britain and South Africa for intravariceal injection, whereas polidocanol is the most commonly used sclerosant for paravariceal injection in Austria and West Germany25). Absolute alcohol appears to be an effective, safe, economical and readily available sclerosant and is easy to inject rapidly because of its aqueous nature26,27). In our study, we used 5% ethanolamine oleate as the sclerosant.

Recent autopsy studies suggest that prolonged variceal obliteration is due to necrosis accompanied by polymophonuclear leukocyte infiltration during the first seven to 10 days and fibrosis after two weeks. Variceal thrombosis is an early and transient event that is detected only if the varix is examined soon after sclerotherapy28–31).

More elaborate methods of injection sclerotherapy have included a means of balloon tamponade in order to maintain a blood-free field during the procedure25). Williams and Dawson32) combined the fiberoptic endoscope with a flexible outer esophageal sheath. In 1980, a flexible sheath became commercially available (Keymed-Williams tube), which was made of mesh-reinforced rubber with graduated markings along its length to enable accurate positioning of the slot at the gastroesophageal injection. Threr is a controversy regarding the use of balloon compression after endoscopic sclerotherapy to retard blood flow and to prolong the contact time of the sclerosant with the variceal wall33).

There is no clear agreement with regard to the ideal interval between endoscopic sclerotherapy courses, and most workers empirically follow a protocol of three to six weeks26). It is argued that intervals shorter than this are associated with problems of esophageal ulcers, stricture formation and poor patient compliance34). Westaby et al.35) conducted a randomized study to compare the efficacy and complication of injection sclerotherapy carried out at intervals of one week and three weeks. The number of courses of injection required for obliteration of the varices was not different in the two groups, and despite a shorter time schedule for obliteration in the weekly treated patients, the frequency with which further episodes of bleeding occurred before that was not significantly less. Mucosal ulceration during the period required for obliteration was observed more frequently on endoscopy in the weekly treated patients but was not associated with a greater frequency of post-injection pain, dysphagia or long-term stricture formation. In our study, we performed sclerotherapy at two-or three-week intervals.

All currently reported experiences with injection sclerotherapy show it to be a highly effective method of arresting acute hemorrhage from esophageal varices in about 90% of the cases36–41). The success rate of stopping acute and massive hemorrhage from varices is 93% with a rigid instrument and 81% with a flexible one14). Of 117 patients with portal hypertension who received a total of 217 injection, hemorrhage was controlled in 93% of admissions36).

The important unanswered question is whether repeated sclerotherapy improves long-term survival. Two major controlled studies using different techniques of intravariceal sclerotherapy have produced conflicting results. The King’s College Hospital trial showed improved survival with sclerotherapy when compared with controls11), whereas Cape Town’s trial did not12).

Terblanche has compared chronic injection sclerotherapy using the rigid esophagoscope with conservative medical management. Rebleeding was frequent in the control group but was uncommon in the injection group42). The King’s study also showed less recurrent bleeding in a group undergoing chronic injection compared with a control group34). Other studies have reported similar encouraging results with chronic injection.

In a retrospective study, DiMagno et al.5) compared the results of 162 patients who underwent endoscopic sclerotherapy from 1980 to 1982 with those of 80 patients treated by other means from 1978 to 1980. When adjusted for Child’s class and etiology of liver disease, no substantial improvement was found in either survival or bleeding-free intervals for patients who underwent sclerotherapy. Also, they reported that some variability in the results among the various studies may be due to differences in technique or the sclerotherapy agent43). In our study, there was a significant difference between the two groups (sclerotherapy vs. non-sclerotherapy) (mean±SEM), such as days of index hospitalization (20.26±11.21 vs. 11.47±9.92), the number of transfusions after discharge of index hospitalization (2.52±5.29 vs. 10.80±14.61 pints) and the bleeding control rate (79.8 vs. 51.0 percent).

A tendency also existed showing that variables related to rebleeding decreased in the sclerotherapy group compared with the non-sclerotherapy group. Especially, the death rate due to bleeding was higher in the non-sclerotherapy group (36.5 percent) than in the sclerotherapy group (14.0 percent).

The complications arising from sclerotherapy range from substernal pain36,37,39–41), esophageal bleeding40–42), ulceration and sloughing of the esophageal mucosa37,40–42), perforation with periesophageal leakage36,37,42), thoracic empyema36) and pleural effusion39), to delayed esophagela necrosis occurring five to 14 days later15,36), broncho-esophageal fistula44), late esophageal stenosis1,2,5,10,16), periesophageal granuloma and portal vein thrombosis45,46).

Major complications of sclerotherapy have occurred in 2–44%36,37,39,41) of injection treatments, although many are primary consequences of rigid esophagoscopy, such as esophageal tears37,40–42) and leakge36,37,42). Anaphylactic reactions have been reported with the peripheral venous injection of morrhuate or ethanolamine, and some have been fatal47–49). The cardiovascular effects ascribed to sclerotherapy have included a ventricular arrhythmia and persistent brady-arrhythmia50). A case of antral varices developed after sclerotherapy was reported51). Esophageal stricture after EIS was easily dilated with metal (Eder-Puestow) dilators26). Transient oliguria and hepatorenal syndrome after sclerotherapy were reported26). In our study, there were 19 complications (16.7%) in 19 patients, such as substernal pain (10 patients), bleeding (three patients), esophageal ulcertion (two patients), pneumonia (two patients), fever (one patient) and sepsis (one patient).

Even with optimal emergency sclerotherapy, the mortality remains at 10 to 50% during the acute phase52,53). For this reason, a prophylactic measure should be the ideal therapy. Prophylactic portacaval shunts were abandoned because prospective controlled trials failed to demonstrate an improved survival2–4), due both to the high risk related to shunting surgery and the impossibility of identifying patients who will bleed during the natural course of the disease, thus resulting in the unnecessary treatment of up to 70% of the patients54).

The ability to predict which patients with cirrhosis and varices will bleed could be of great benefit, since both propranolol and sclerotherapy have low procedure-related mortality. And prophylaxis with both sclerotherapy and propranolol decreases the incidence of bleeding and prolongs survival for cirrhotics with varices that have never bled55).

Prediction of bleeding from varices has been attempted by numerous authors with limited success. Prediction schemes have been based on the size of the varices56), the endoscopic appearances of the varices57–59) and consideration of other clinical factors60–62). Moreover, Beppu and associates58) have noted that large, tortuous, blue, panesophageal varices are those most commonly associated with variceal hemorrhage. Specific signs of abnormalities of the variceal wall can be recognized from the endoscopic appearance of the varices as a predictor of variceal hemorrhage. Endo and Fujita57) reported that the RCS (red color sign) did appear to be the most important endoscopic sign that correlated with bleeding. Graham and Smith1) reported that a characteristic pattern of red marking on the variceal wall and the simultaneous presence of fundic varices were the only variables that correlated significantly with bleeding in patients with large varices.

Prophylactic sclerotherapy has had a favorable effect in two trials62,63). Paquet65) described a controlled trial of prophylactic sclerotherapy in which the presence of large varices with overlying “black points” at endoscopy or the presence of large varices plus a prothrombin index of less than 30 percent (or both) were used as the criteria of impending hemorrhage in the selection of patients. These critieria proved to be extremely reliable: 66 percent of the control patients bled during a two-year follow-up. However, Sauerbruch et al.66) reported that prophylactic sclerotherapy does not significantly reduce the risk of bleeding from esophageal varices excep in subgroup of patients with esophageal varices and moderately decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis.

The role of prophylactic endoscopic sclerotherapy is not yet defined. It’s value is based on the assumption that recurrent variceal hemorrhage is prevented if esophageal varices can be eradicated11,67). Unfortunately, this assumption is not supported by many authors67–69).

Prophylactic treatment of patients with a high risk of bleeding from varices would be useful if, ideally, it prevented bleeding, prolonged survival and had a low incidence of operative mortality and complications. However, the precise role of sclerotherapy and propranolol, alone or in combination, for prophylactic treatment of varices has yet to be cleraly defined55).

Further prospective studies are necessary to verify the suggestion that endoscopic findings must be integrated with evaluations of hepatic functional reserve in defining the actual bleeding risk, as well as to answer whether prophylactic sclerotherapy has different effects on bleeding and survival in cirrhotics with varying severity of liver disease70).

Prophylactic sclerotherapy at present cannot be a routine procedure but should be limited to randomized controlled trials70). In our opinion, prophylactic sclerotherapy is an effective method if we can select a patient who will bleed.

The conclusions that can be reached from this study are that variceal sclerotherapy is effective, has minimal complications and appears to be superior to conventional medical treatments. However, firm conclusions still await trials with larger numbers of patients and longer periods of follow-up.