A Case of Pseudomembranous Colitis Associated with Rifampin

Article information

Abstract

Pseudomembranous colitis is known to develop with long-term antibiotic administration, but antitubercular agents are rarely reported as a cause of this disease. We experienced a case of pseudomembranous colitis associated with rifampin. The patient was twice admitted to our hospital for the management of frequent bloody, mucoid, jelly-like diarrhea and lower abdominal pain that developed after antituberculosis therapy that included rifampin. Sigmoidoscopic appearance of the rectum and sigmoid colon and mucosal biopsy were compatible with pseudomembranous colitis. The antitubercular agents were discontinued and metronidazole was administered orally. The patient’s symptoms were resolved within several days. The antituberculosis therapy was changed to isoniazid, ethambutol and pyrazinamide after a second bout of colitis. The patient had no further recurrence of diarrhea and abdominal pain. We report here on a case of pseudomembranous colitis associated with rifampin.

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial therapy can predispose a patient to pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) by altering the normal colonic flora and allowing the multiplication of C. difficile. Antitubercular agents does not frequently cause PMC, but we have documented a case of PMC associated with rifampin (RFP) administration.

CASE REPORT

In December 2002, a 90-year-old man was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis via an abnormal chest X-ray and an AFB smear that was done on his bronchial washing fluids. He was treated with antitubercular agents, including isoniazid (INH; 400 mg/day), rifampin (RFP; 600 mg/day), pyrazinamide (PZ; 1500 mg/day), and ethambutol (EMB; 800 mg/day). Thereafter, the findings on his chest X-ray gradually improved, but he complained of intermittent loose stool.

1 month later, his diarrhea took a turn for a worse: it was bloody and mucoid with a jelly-like appearance and he suffered from lower abdominal cramping pain. In February 2003, the patient was admitted to our hospital because of frequent bloody, mucoid, jelly-like diarrhea and lower abdominal pain. He had a poor oral intake of food and drink due to his continuing diarrhea, which occurred 4 to 5 times per day. The patient was afebrile and his vital signs were normal. His breathing sounds were still coarse on both lung fields and his bowel movements were very frequent. The abdomen was soft and flat, but tenderness was noted on LLQ area without rebound tenderness. His white blood cell count was 13,600/mm3 with 54.2% segmented neutrophils. The stool culture was negative for C.difficile toxin and salmonella-shigella. Sigmoidoscopy revealed multiple yellowish plaque lesions from the rectum to the sigmoid colon (Figure 2A), and mucosal biopsy from the sigmoid colon showed chronic inflammation with mucous exudates (Figure 3). There was the strong likelihood that the antitubercular agents were causing PMC, so we discontinued these agents. After oral metronidazole 250 mg three times a day and conservative therapy with intravenous fluid and electrolytes, the symptoms of the patient were ameliorated and then the patient was discharged.

Sigmoidoscopic appearance of the colon. (A) At admission (1.5 months later after the antitubercular agents were started), the sigmoidoscope procedure revealed multiple yellowish plaque lesions from the rectum to sigmoid colon. (B) At readmission (1 month later after the antitubercular agents were restarted), it shows diffuse white plaque and debris on the colonic mucosa from the rectum to the sigmoid colon, with scattered whitish erosion. (C) 2 months later after the antitubercular agents were retried with regimen of 3 drugs except RFP, sigmoidoscopy shows a nearly improved state of colitis and no evidence of recurrence of PMC.

Sigmoidoscopic mucosal biopsy. Mushroom-shaped pseudomembrane is made up of inflammatory cells, fibrin, and necrotic debris (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×40).

After 2 weeks, we restarted antitubercular agents with the 4 drugs regimen (HERZ) at the same initial doses. The patient again developed abdominal pain and diarrhea within only 3days after the retreatment with antitubercular agents. So the patient occasionally withheld the antitubercular agents by himself according to symptom, and when symptoms were relieved, he restarted taking the drugs.

Only 3 weeks after discharge, he admitted with complains of mucoid, bloody diarrhea, severe abdominal pain and fever up to 38.4°C. His chest X-ray showed little change during this interval compared with the previous films (Figure 1). The white blood cell count was 20,200/mm3 with 78.7% segmented neutrophils. We stopped all medication including the anti-tubercular agents except the metronidazole. For 3 days, conservative management was done including fluid therapy and fasting, but he did not show improvement. So sigmoidoscopy was again done and it revealed diffuse white plaque and debris on the colon mucosa from the rectum to the sigmoid colon, with scattered whitish erosion (Figure 2B). Mucosal biopsy of the colon was compatible with a diagnosis of PMC on account of the ulceration with exudates of a pseudomembrane made up of inflammatory cells, fibrin, and necrotic debris. C. difficile toxin and stool culture were negative. 11 days after admission, the patient’s symptoms were much resolved and follow-up sigomidoscopy demonstrated a much improved state of the colitis. 2 days later, the antitubercular agents were retried with regimen of 3drugs without the RFP (INH 400 mg, PZ 1500 mg, EMB 800 mg) and we observed the patient for another 10 days. The patient had no further recurrence of diarrhea, and he recovered his general condition; the follow-up sigmoidoscopy did not show any evidence of recurrent PMC (Figure 2C), and he was then discharged.

(A) Initial chest PA at the time of diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Chest PA shows multiple irregular pathological consolidations on both lung fields. (B) Follow up of chest PA on admission (1.5 months later after antitubercular agents were started). Chest PA shows further improvement of the multiple irregular pathological consolidations on both lung fields.

DISCUSSION

Nowadays, the increasing use of antibiotics induces many complications including PMC. C. difficile infection is responsible for virtually all the cases of PMC and for up to 20 percent of cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhea without colitis. Almost any antibiotic may cause C. difficile infection, but the broad-spectrum antibiotics with activity against enteric bacteria are the most frequent causative agents1).

Antitubercular agents do not frequently cause PMC, but a few cases of rifampin associated PMC have been reported since the 1980s. Among all the antitubercular agents, rifampin has implicated as a cause of PMC due to its relatively wide range of antibiotic effects whereas INH and EMB have little or no effects on the intestinal flora2). Most of the C. difficile strains are susceptible to rifampin3), but resistance can develop afters prolonged use4).

The clinical manifestations of PMC usually appear as watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever and leukocytosis, but severe diarrhea can develop an electrolyte imbalance, hypoalbuminemia and a generalized edema. On rare ocassion, PMC patients can have fatal complication like toxic megacolon, necrotizing colitis and colon perforation5). On the sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy findings, a 2–8 mm in diameter elevated cream-colored pseudomembrane is observed that is localized to rectum and sigmoid colon. It sometimes invades the ascending colon, but there is no erosion or ulceration at this site. On the histologic findings, this pseudomembrane is composed of fibrinoid material, leukocytes and epidermal debris, and the entire mucosa and lamina propria are infiltrated by leukocytes as well6).

In this case, we could not prove C.difficile on the stool culture or ELISA, but this case had the typical sigmoidoscopic findings. We could not check for antibiotics sensitivity (like for rifampin resistance) because we couldn’t isolate the C. difficile. The best method to ascertain if the rifampin induced the PMC is by retrial with a single regimen of rifampin and then to observe if there is recurrence of PMC. However we could not retry rifampin because the patient was very old and in a poor general condition from his prolonged illness. But the PMC developed twice on the drug regimen that included rifampin, and it did not develop on the regimen that excluded rifampin. This strongly suggests that rifampin was the causative agent of PMC in this case.

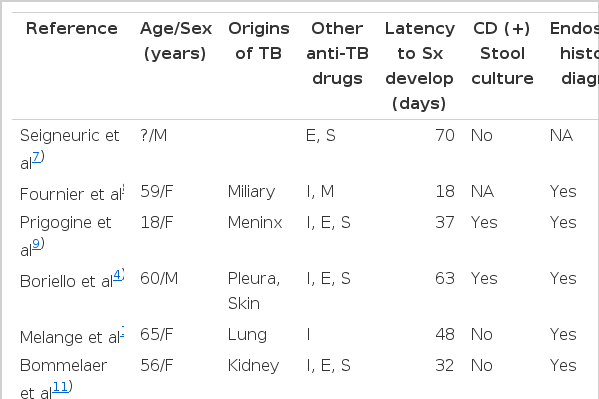

There are a few studies reporting that rifampin induced PMC (Table 1). The age of these patients varies, ranging from 18 years to 90 years, and mean age is 57.2 years. There is no significant difference in sex distribution. The latency period to develop PMC after initiation of antituberculosis medication has a wide range of 7 days to 120 days (mean, 48.6 days). The patients usually improved their symptom under treatment with vancomycin or metronidazole, and one patient recovered with lactic acid bacilli only. Oral therapy with metronidazole 250 mg, 4 times a day for 10 days is the recommended first-line therapy. Vancomycin (125–500 mg, 4 times a day for 10 days) should be limited to those who cannot tolerate or have not responded to metronidazole, or due to the increased development of metronidazole-resistent orgenisums such as enterococci18). There is usually a therapeutic response within a few days, but recurrence of symptoms after discontinuation of antibiotics occurs in 20% of cases, and this is associated with the persistence of C. difficile in the stools. The yeast Saccharomyces boulardii has been proven in controlled trials to reduce recurrences when given as an adjunct to antibiotic therapy19). Nakajima et al. observed that old age, immunosuppression, hospitalization, and procedures or medications that alter intestinal motility or the intestinal flora would be major risk factor of antibiotics associated PMC. Some authors have indicated that oral antibiotics may induce PMC more frequently2).

When managing aged, tuberculosis infected patient, like this case, we have to keep in mind the possibility of antituberculosis agent associated PMC. When such patient complains gastrointestinal problem like diarrhea or abdominal pain, PMC should be included in the differential diagnosis.