A Phase II Study of Vinorelbine, Mitomycin C and Cisplatin Chemotherapy for Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Article information

Abstract

Background

This prospective phase II trial was performed to determine the efficacy and toxicity of mitomycin C, vinorelbine and cisplatin combination chemotherapy for patients with previously untreated stage IIIB or IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods:

Between January 7999 and April 2001, 30 patients with chemotherapy-naive stage IIIB or IV NSCLC were entered into this study. Mitomycin C at a dose of 7 mg/m2, vinorelbine at a dose of 25 mg/m2 and cisplatin at a dose of 75 mg/m2 on day 1 and vinorelbine at a dose of 25 mg/m2 on day 8 were administered. This regimen was repeated every 4 weeks.

Results:

29 patients out of 30 patients were assessable. Among the assessable patients, 15 (51.7%) patients had a partial response. The median duration of response and survival was 22 weeks and 39 weeks, respectively. Grade 3 or 4 leukopenia and thrombocytopenia were observed in 28.3% and 4.7% of all the cycles, respectively. Nausea and vomiting of grade 3 occurred only in 2.4% of all the cycles.

Conclusion:

The regimen of mitomycin C, vinorelbine and cisplatin for non-small cell lung cancer is active against advanced NSCLC with tolerable toxicities.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is a common medical problem in most countries and the incidence has increased to the second most leading cause of death from malignancies in Korea1). Non-small cell lung cancer accounts for approximately 75% of all lung cancers2). The only curative modality for non-small cell lung cancer is curative resection with early detection. However, the early detection rate is only about 14% in Korea and most patients need chemotherapy2).

The progress in chemotherapy of non-small cell lung cancer is only modest. But important new drugs, such as vinorelbine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, gemcitabine, edatrexate and irinotecan, have been investigated.

Among these, vinorelbine had a response rate of 33%3) in previously untreated patients. Vinorelbine prolonged survival duration with single therapy compared to 5-FU and leucovorin combination chemotherapy4). Moreover, synergistic activity was reported when vinorelbine was combined with cisplatin. The combination of vinorelbine and cisplatin yielded a higher response rate (30% vs 14%) and a longer median survival duration (40 weeks vs 31 weeks) than vinorelbine single therapy5). The combination of vinorelbine and cisplatin is also more active than cisplatin single agent with a higher response rate (26% vs 12%) and a longer median survival duration (8 months vs 6 months)6). The combination regimen of vinorelbine and cisplatin has now become a new standard for non-small cell lung cancer, with activity comparable to the combination regimen of mitomycin C, vindesine and cisplatin (MVP regimen) which is well-known as a traditional standard7). Mitomycin C is also active in non-small cell lung cancer. The addition of mitomycin C to a combination regimen of cisplatin and vindesine increased the response rate8). Substitution of vinorelbine for vindesine in a cisplatin-mitomycin -vinca alkaloid chemotherapeutic regimen resulted in an improvement in response rate (38% vs 57%) and median survival duration (8 months vs 12 months)9).

These observations suggest that the addition of mitomycin C to a combination chemotherapeutic regimen of vinorelbine and cisplatin might have a high anti-tumoral efficacy. So, we undertook a phase II study of vinorelbine, mitomycin C and cisplatin combination chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer to determine the efficacy and safety of this regimen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1) Eligibility criteria

Patients had to fulfil the following criteria to be eligible for this study: histologically or cytologically proven non-small cell lung cancer; stage IV or selected stage IIIB disease that is not an indication for curative resection or curative RT; at least one measurable lesion; good performance status (ECOG 0–2); no previous history of chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy; and adequate bone marrow (granulocyte≥1,800/μL, platelet≥100,000/μL), hepatic (total bilirubin≤2.0 mg/dL) and renal (creatinine clearance≥50 mL/min) functions. An informed written consent was obtained from all patients.

2) Treatment schedule

Mitomycin C at a dose of 7 mg/m2, vinorelbine at a dose of 25 mg/m2 and cisplatin at a dose of 75 mg/m2 on day 1 and vinorelbine at a dose of 25 mg/m2 on day 8 were administered. The regimen was repeated every 4 weeks.

The hematologic toxicities were assessed by checking weekly CBC (complete blood count). The dose of mitomycin C and vinorelbine was reduced by 10% in the next cycles in the event of grade 4 hematologic toxicity.

The dose of vinorelbine on day 8 was modified as follows according to CBC on the day of vinorelbine administration. It was reduced to 50% of the planned dose if the granulocyte count was 1,000–1,490/μL and/or the platelet count was 50,000–74,900/μL. The administration of vinorelbine was omitted if the granulocyte count was below 1,000/μL and/or the platelet count was below 50,000/μL.

Based on the CBC just before the next cycle of chemotherapy, the treatment was postponed until bone marrow functions recovered and granulocyte and platelet count were at least 1,800/μL and 100,000/μL, respectively. According to the creatinine clearance before chemotherapy, the dose of cisplatin was modified as follows; cisplatin was admininstered at a full dose with creatinine clearance at or above 50 mL/min and reduced to 50% with creatinine clearance 30–49 mL/min. The study was withdrawn at a creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min.

The antiemetic agents of HT3 antagonists and dexamethasone were used routinely to prevent nausea and vomiting. Adequate hydration was effected from the day before administration of cisplatin to prevent renal toxicities. Cytokines, such as G-CSF or GM-CSF, were administered if needed.

This treatment was discontinued at the time of disease progression or appearance of unacceptable toxicities.

3) Treatment evaluation and statistical considerations

CBC, blood chemistry, chest X-ray and physical exam were repeated before every chemotherapy cycle. The follow-up studies of computerized tomography and bone scan were performed every 2–3 cycles of chemotherapy. Response and toxicities were evaluated in accordance with WHO criteria.

Overall survival was calculated from the time of chemotherapy to death. The duration of response was defined as the interval between the day when the objective response was confirmed with imaging studies and the time of disease progression. Both overall survival and duration of response were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

RESULTS

1) Patient characteristics

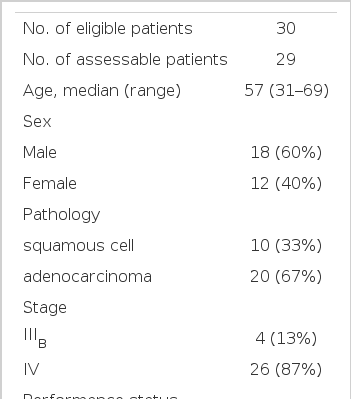

Between January 1999 and April 2001, 30 patients (12 women, 18 men) were enrolled in this study.

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age of patients was 57 years, ranging from 31 to 69 years. At the time of inclusion, 26 patients (87%) had metastatic stage IV disease, whereas 4 patients (13%) had stage IIIB disease. 6 patients (20%) had a ECOG performance grade of 0, 16 patients (53%) of 1 and 8 patients (27%) of 2. 20 patients (67%) had adenocarcinoma and 10 patients (33%) had squamous cell carcinoma.

2) Response and overall survival

Responses were evaluable in 29 patients out of 30. Response in 1 patient was not evaluable because of early death. The median follow-up duration was 25 weeks (range 5–63 weeks).

Among the evaluable patients, 15 (51.7%) had a partial response, 9 (31.0%) had a stable disease and 5 (17.2%) had a progressive disease (Table 2). The response rate was 51.7% (95% confidence interval: 34.4–68.6%). The median response duration (Figure 1) was 22 weeks (range 1+–34 weeks). The median survival duration (Figure 2) was 39 weeks (range 5–63+ weeks).

3) Toxicities

A total of 127 cycles of chemotherapy were administered (median 4 cycles per patient). The toxicities observed after chemotherapy are summarized in Table 3. The main problem was hematologic toxicities, including granulocytopenia and thrombocytopenia. Grade 3 granulocytopenia occurred in 17 cycles (13.4%) and grade 4 granulocytopenia in 19 cycles (15.0%). Grade 3 and 4 thrombocytopenia occurred in 3 cycles (2.4%), respectively. Grade 3 or 4 infection occurred in 2 patients with chemotherapy-related granulocytopenia and, among them, 1 patient died of sepsis. A patient developed hemolytic anemia probably due to mitomycin C and was put off the protocol.

Non-hematologic toxicities were also observed. Nausea/vomiting of grade 3 occurred in 3 cycles (2.4%). However, other non-hematologic toxicities, including stomatitis and nephrotoxicities greater than grade 2, were not observed.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the MNP (mitomycin C, vinorelbine and cisplatin) combination chemotherapy yielded a high response rate of 51.7% (95% confidence interval: 34.4–68.6%) for non-small cell lung cancer patients. This response rate is higher than that of the vinorelbine and cisplatin combination chemotherapy reported by Le Chevalier (29.7%, 95% confidence interval: 26.4–34.0%)5). However, the incidence of grade 3 or 4 granulocytopenia in this study was much lower than that in Le Chevalier’s report (28.3% versus 78.7%). In Le Chevalier’s study, vinorelbine was administered at a dose of 30 mg/m2 per week and cisplatin of 120 mg/m2 per 4 weeks. So, the planned dose-intensity of that regimen was 30 mg/m2/week of vinorelbine and 30 mg/m2/week of cisplatin. In our MNP regimen, the planned dose-intensity was 10 mg/m2/week of vinorelbine and 19 mg/m2/week of cisplatin, which is lower than that of Le Chevalier’s vinorelbine-cisplatin regimen. The lower dose-intensity of our regimen may probably be associated with lower incidence of hematologic toxicities.

In SWOG’s report of vinorelbine and cisplatin combination chemotherapy6), the dose-intensity was 25 mg/m2/week of vinorelbine and 25 mg/m2/week of cisplatin. This regimen produced a response rate of 26% (95% confidence interval: 20–32%) with 81% of grade 3 or 4 granulocytopenia. In comparison with the SWOG’s report, our MNP regimen planned a lower dose-intensity of vinorelbine and cisplatin and showed lower incidence of granulocytopenia but showed significantly higher response rate.

This response rate of the MNP regimen is similar to that of the mitomycin C, vinorelbine and cisplatin combination regimen reported by Furuse10) (63.2%). These suggest that the addition of mitomycin C to the vinorelbine and cisplatin combination regimen for non-small cell lung cancer may increase the response rate.

For the regimen containing other vinca-alkaloids, the addition of mitomycin C to vindesine and cisplatin combination chemotherapy (VP) for non-small cell lung cancer showed a higher response rate (42.8% in MVP versus 28.6% in VP)7). This report also suggests that the addition of mitomycin C to a regimen of vinca-alkaloid and cisplatin for non-small cell lung cancer may increase the response rate.

The median survival time of this study was 39 weeks. This was not significantly different from that with the vinorelbine and cisplatin combination chemotherapy reported by Le Chevalier (40 weeks)5) and by SWOG (32 weeks)6). Why is it that the addition of mitomycin C did not prolong overall survival duration in spite of a higher response rate and lower incidence of hematologic toxicities? There may be two possible explanations. First, the size of the sample was so small that the survival duration was not measured accurately. Second, the duration of response of this regimen was not long enough to lengthen the survival duration. As pointed out by Takahashi and Nishioka, the progression-free duration would be more critical than the response rate to prolong the survival of cancer patients, especially if the progression-free duration lasts more than 90 days11). To answer this problem, a prospective randomized study comparing vinorelbine-cisplatin with mitomycin-vinorelbine-cisplatin would be needed.

This is not a comparative study and the different patient characteristics make it difficult to compare the results of this study to those of others. Nevertheless, this study suggests that the addition of mitomycin C to vinorelbine-cisplatin combination chemotherapy may result in a higher response rate. Further studies may be warranted to explain why the increased response rate did not translate into a longer survival duration. The value of adding mitomycin C to the combination of vinorelbine and cisplatin for non-small cell lung cancer may be answered by a prospective randomized trial.

CONCLUSION

The combination chemotherapy regimen of mitomycin C, vinorelbine and cisplatin was safe and active for non-small cell lung cancer.