Mycobacterium Avium Complex Infection Presenting as an Endobronchial Mass in a Patient with Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

Article information

Abstract

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection is a common opportunistic infection in patients with AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome). Pulmonary involvement of MAC may range from asymptomatic colonization of the respiratory tract to invasive parenchymal or cavitary disease. However, endobronchial lesions with MAC infection are rare in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed hosts. Here, we report MAC infection presenting as an endobronchial mass in a patient with AIDS.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is well-known as a common opportunistic organism in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)1). MAC also acts as a pulmonary pathogen in immunocompetent patients with underlying structural lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and bronchiectasis, as well as in destructive lung lesions like those observed previously in diagnosed tuberculosis2). Pulmonary involvement of MAC may range from airway colonization to invasive parenchymal disease. Pulmonary parenchymal disease with MAC occurs rarely in patients with HIV in the absence of dissemination3).

Endobronchial involvement due to M. tuberculosis is a well-described and a relatively common manifestation of tuberculosis in the Republic of Korea4). However, endobronchial lesions involved in MAC infection are rarely found in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed hosts5, 6). There have been few reports of an endobronchial presentation of MAC infection in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)6-11). Here, we report an MAC infection presenting as an endobronchial mass in a patient with AIDS receiving anti-retroviral chemotherapy.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old male was admitted to the hospital because of cough with sputum lasting for seven days. He was known to be HIV-positive from a diagnosis made eight months previously. Five months prior to admission, he was diagnosed with Pneumocystis carinii (P. carinii) pneumonia (PCP), cytomegalovirus (CMV) pneumonia, and herpes zoster infection on the skin. He was then started on lamivudine, zidovudine, and indinavir as anti-retroviral therapy and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole as PCP prophylaxis. At that time, his CD4 and CD8 lymphocyte counts were 356/mm3 and 1546/mm3, respectively, and his CD4/CD8 ratio was 0.23. His HIV viral load (measured by Roche Amplicor RT-PCR) was 670,000 copies/mL. Seven days prior to admission, the patient presented with a cough that produced sputum and a three-day history of fever.

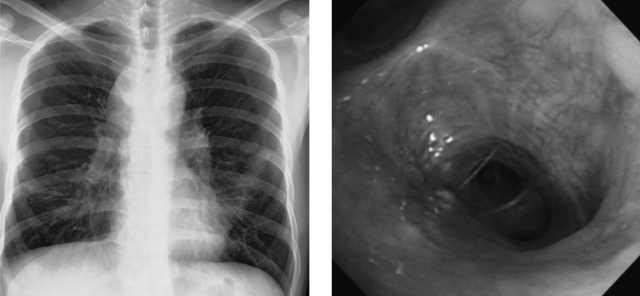

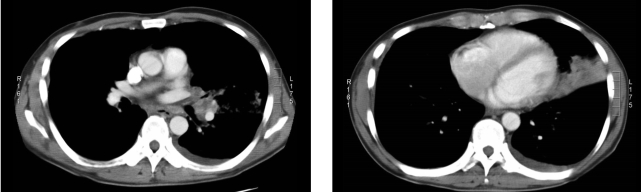

On admission, the physical examination showed inspiratory crackles at the left lower lung field on chest auscultation. The patient was not febrile or tachypneic. The chest radiograph demonstrated an increased opacity, with obliteration of the cardiac border at the lower left lobe of the lung and bilateral hilar enlargement (Figure 1). In addition, the computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest demonstrated irregular bronchial narrowing and consolidation at the lingular segment of the left upper lobe, and also showed bilateral hilar and subcarinal lymphadenopathy (Figure 2). Bronchoscopic examination revealed a polypoid mass-like lesion of approximately 1 cm in diameter that was occluding the lingular division of the left upper lobe of the lung (Figure 3).

Chest radiograph shows increased haziness at the left lower lung field with obliteration of the cardiac border; this indicates a lobar pneumonia at the lingular division of the upper lobe and bilateral enlargement of the suprahilar area with a prominent left hilum.

Chest CT scan shows irregular bronchial narrowing with consolidation in the lingular division of the left upper lobe. Small pleural effusion and hilar lymphadenopathy are also noted.

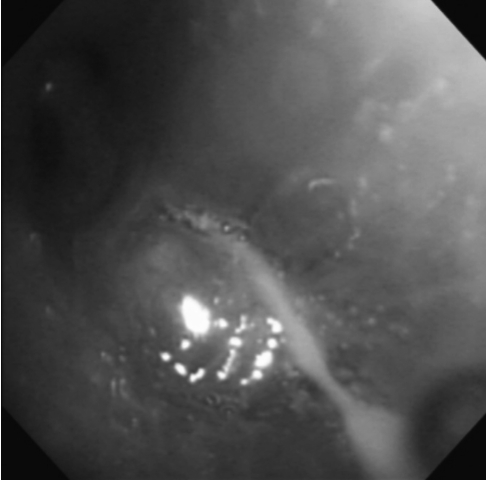

Bronchoscopic examination shows a polypoid smooth-surfaced mass lesion that completely occluded the lingular division of the left upper lobe bronchus.

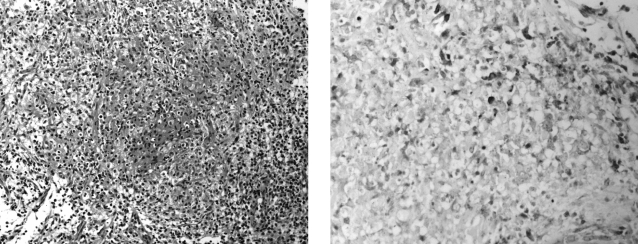

Biopsy of the lesions revealed granulomatous inflammation with epitheloid cells without caseation necrosis (Figure 4). Bronchial washing fluid showed small numbers of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) on Ziehl-Neelsen staining (Figure 4). The patient was treated with isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide following the diagnosis of endobronchial tuberculosis. His respiratory symptoms were improved and the chest radiograph showed a slightly improved state in the left lung field after the initiation of treatment. After two months of treatment with anti-tuberculosis medication, M. avium was cultured from his expectorated sputum and bronchial washing fluid. The medication was then changed to rifabutin 150 mg/day, ethambutol 1,200 mg/day, and clarithromycin 1,000 mg/day. Two months after this change in treatment, the patient was asymptomatic and his chest radiograph was improved. Bronchoscopic examination showed mild fibrotic changes without the presence of a mass-like lesion at the lingular division of the left upper lobe (Figure 5). At this time, five months after the initiation of combination anti-retroviral therapy, his CD4 and CD8 cell counts were 227/mm3 and 828/mm3, respectively, and his CD4/CD8 ratio was 0.27. His viral load was less than 25 copies/mL.

Microscopic examination shows granulomatous inflammation with non-caseation necrosis (H&E, ×200) (left). Acid-fast stain of the bronchial washing fluid demonstrates numerous mycobacterium within macrophages (Ziehl-Neelsen stain, ×400) (right).

DISCUSSION

This is the first report of an endobronchial mass caused by MAC infection in a patient with AIDS in the Republic of Korea. In a report on opportunistic infections of HIV/AIDS patients in the Republic of Korea, published in 2003, tuberculosis was the third most common opportunistic infection, and was the most common initial infection identified when patients first presented with AIDS12). Atypical mycobacterial infection accounted for only six cases (4%) in 150 AIDS patients, and the specific type of atypical mycobacterium was not described12). There has been one case report of Mycobacterium avium complex-intracellular (MAI) meningoencephalitis in a patient with AIDS and preexisting disseminated MAC infection from the Republic of Korea13). There was a recently published report of endobronchial lesions caused by Mycobacterium avium Infection in an immunocompetent 21-year-old patient with no preexisting lung disease14).

Although isolated pulmonary involvement with MAC is relatively common in immunocompetent hosts, it is uncommon in patients with AIDS11). Because isolated pulmonary involvement with MAC is rare, and given the high frequency of colonization in bronchial trees, histological confirmation is required to support positive cultures from respiratory specimens15). For the patient reported here, several sputum cultures and the bronchial washing fluid culture showed mycobacterium, specifically MAC, and the histological examination showed granulomatous inflammation with epitheloid cells in the bronchoscope biopsy specimen. Because the histological examination usually does not distinguish M. tuberculosis from MAC, culture for mycobacterium is required to confirm MAC infection15). At first, a malignant tumor was suspected because the lung and bronchoscopic findings showed a polypoid mass that completely occluded the lingular division of the left upper lobe of the lung. However, the diagnosis of pulmonary infection with MAC was confirmed by repeated sputum culture, bronchial washing fluid culture, and histological examination.

It has been suggested that endobronchial disease with MAC results from the restoration of the immune response during anti-retroviral therapy (immune reconstitution syndrome)8, 16, 17). It has been hypothesized that patients may experience a subclinical infection that becomes clinically manifest as host cellular immunity recovers after the initiation of anti-retroviral therapy. This suggests that the host immune response is a cofactor in causing disease. When MAC infection is due to the immune reconstitution syndrome, the symptoms are expected to appear within two to four weeks after the initiation of anti-retroviral therapy.

The patient reported here was diagnosed with P. carinii pneumonia and CMV pneumonia prior to the diagnosis of MAC infection. Following diagnosis, the patient was started on anti-retroviral therapy. After several months of anti-retroviral therapy, isolated pulmonary infection with MAC developed. In this case, the development of MAC infection, after the initiation of anti-retroviral therapy, occurred over a longer interval than that reported previously16, 17).

The clinical features of isolated pulmonary MAC infection in patients with HIV include: fever, cough, and night sweats, and are often accompanied by dyspnea, hemoptysis, and/or weight loss. Radiographic patterns have included mediastinal adenopathy, patchy bilateral alveolar infiltrates, nodular infiltrates, and normal findings on chest roentgenograms. Blood cultures are normally negative for MAC18). Treatment of isolated pulmonary MAC infection is usually successful, with favorable outcomes described in 21 of 21 reported cases11, 19).

In conclusion, patients with HIV/AIDS who present with respiratory symptoms and a chest radiograph with lung infiltrates and adenopathy during anti-retroviral therapy should be evaluated for potentially isolated pulmonary MAC infection.