Adrenocorticotropic hormone-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia with abnormal cortisol secretion mediated by catecholamines

Article information

To the Editor,

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (AIMAH) is a rare cause of Cushing syndrome. In AIMAH, cortisol secretion is independent of ACTH, and various hormones and/or cytokines have been thought to stimulate cortisol secretion via the aberrant expression of adrenal receptors or the increased activity of eutopic hormone receptors. Schorr and Ney [1] first proposed this concept, and subsequently the ectopic expression of gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP), V2 and V3-vasopressin, β-adrenergic, luteinizing hormone (LH)/human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), serotonin, and angiotensin receptors, as well as increased activity of a eutopic V1-vasopressin receptor, have been identified in the adrenal gland [1,2]. Several genetic factors, such as Gs α-subunit mutations associated with McCune-Albright syndrome and MC2R (ACTH receptor gene) mutations, have also been postulated as causes of AIMAH.

A 50-year-old male was referred and admitted to our hospital due to uncontrolled hypertension. He had suffered from hypertension for 6 years. His blood pressure was originally well controlled for the first 5 years using a calcium channel blocker, but poorly controlled for 1 year before he visited our hospital, despite his regular use of antihypertensive agents. He was initially referred to the Cardiology Department and underwent cardiologic evaluation after complaining of paroxysmal palpitation and dizziness. His 24-hour Holter monitoring and coronary angiographic results were normal, except for several antigen-presenting cells and a minimal coronary arterial obstruction at the middle left anterior descending artery. He had a past history of major depression and had been prescribed an antidepressive agent 18 months before he visited our hospital.

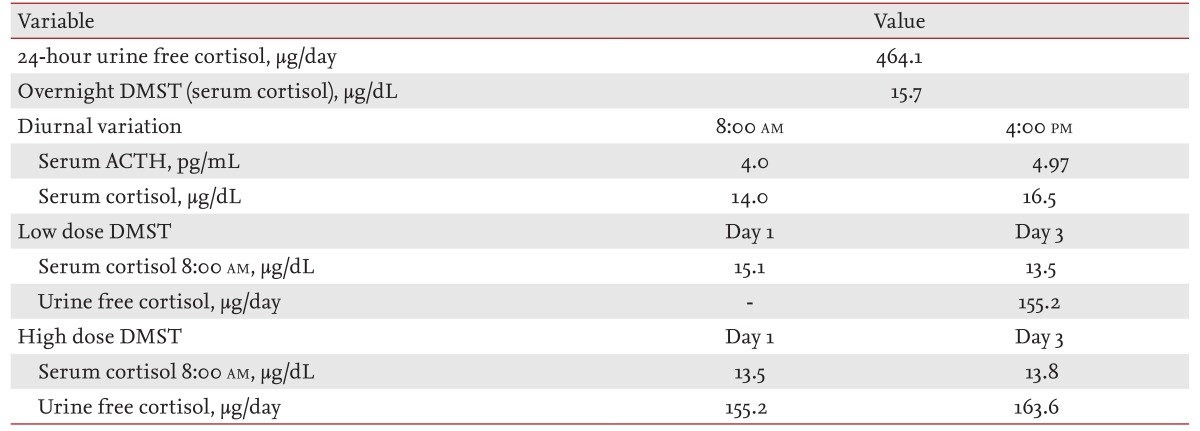

On physical examination, he had a moon face, marked central obesity (height, 167 cm; weight, 77.65 kg; body mass index, 27.84 kg/m2), and multiple bruises on his extremities. He also had prominent purple abdominal striae, and all of his morphological features were consistent with Cushing syndrome. Laboratory examinations revealed 145.7 mEq/L serum sodium and 2.86 mEq/L serum potassium. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.519, HCO3, 37.4 mM/L). His hemoglobin A1c level was 5.9%, and his serum fasting blood glucose was 118 mg/dL. The results of basal endocrinological examinations are summarized in Table 1. The circadian variation in serum cortisol production was disrupted, and basal ACTH levels were suppressed. A 24-hour urinary free cortisol test and overnight dexamethasone suppression test (DMST) were both suggestive of Cushing syndrome. Low- and high-dose DMST revealed Cushing syndrome of primary adrenal origin. An abdominal computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed bilateral large macronodular adrenal tumors. His pituitary gland was normal on brain MRI scans. We thus diagnosed this patient with Cushing syndrome secondary to AIMAH.

To identify aberrant receptors on the adrenal gland, we followed the investigative protocol described by Lacroix et al. [3]. Postural and various provocation tests, including ACTH (250 µg, intravascular), arginine vasopressin (AVP; 10 IU, intramuscular), 5-hydroxy triptamine (5-HT; 10 mg, intravascular), isoproterenol (20 ng/kg/min, intravascular for 30 minutes) and mixed meal tests, were performed. His serum cortisol level showed a positive response to ACTH, AVP, and isoproterenol provocation tests, but a negative response to the postural stimulation test. The results are summarized in Fig. 1A. If the patient had β-adrenergic or AVP receptors on his adrenal gland, then he would have responded to the postural stimulation test; but he did not. We repeated the postural stimulation test, and checked his endogenous antidiuretic hormone (ADH) level. He exhibited an increased ADH level on the postural test, but no cortisol secretion (Fig. 1B).

Various provocative tests for cortisol secretion. (A) Serum cortisol levels were increased in response to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), arginine vasopressin (AVP), and isoproterenol infusion; however, there was a negative response in the postural test. (B) Postural stimulation induced antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and aldosterone, but not cortisol, secretion.

5-HT, 5-hydroxy triptamine.

A bilateral adrenalectomy was performed. The subsequent pathological examination of both adrenal glands showed hyperplasia with a multinodular growth pattern: the right and left adrenal glands were sized 14.0 × 5.0 × 3.0 cm and 9.0 × 5.0 × 3.0 cm, respectively, and multiple golden yellow nodules measuring up to 4 cm in diameter were present. Microscopic findings showed that the nodules consisted of variable-sized nests of lipid-laden clear cells similar to those of the normal fasiculata layer (Fig. 2). The final clinical and pathological diagnosis was Cushing syndrome secondary to β-adrenergic agonist-responding AIMAH. After the operation, he took physiological doses of prednisolone and fludrocortisone. He then lost weight gradually and achieved optimal blood pressure with reduced doses of antihypertensive agents.

Pathological findings of the resected adrenal gland. (A) Gross findings showed multinodular golden yellow soft tissue. (B) Microscopic view (H&E, ×400) revealed nodular hyperplasia composed of lipid-rich and lipid-poor cells.

Kirschner et al. [4] first described AIMAH in 1964. They demonstrated that hypercortisolism was ACTH-independent, and that the resected adrenal glands contained multiple nodules. Since then, a number of cases have been described, and the cause of AIMAH has been characterized more precisely. Previously, steroid production in AIMAH was believed to be autonomous. In the previous study that compared the adrenal glands of patients with AIMAH to those in patients with long-standing Cushing disease, and concluded that prolonged adrenal stimulation by ACTH resulted in adrenal bilateral nodular formation and varying ranges of adrenal autonomy [5]. There were also some cases in which autonomy of the adrenal gland was the result of chronic ACTH stimulation, which eventually resulted in ACTH suppression. However, the rarity of Nelson syndrome following bilateral adrenalectomy in patients with AIMAH strongly argued against the adrenal autonomy hypothesis.

In 1971, Schorr and Ney [1] first introduced the concept of aberrant adrenal receptor expression in adrenocortical tissue. They performed in vitro studies, and found that cyclic adenosine monophosphate and corticosterone production in rat adrenocortical carcinoma cells were stimulated by non-ACTH hormones such as catecholamines, thyroid stimulating hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, LH, and prostaglandin E1. This hypothesis was later validated in humans by additional in vitro and in vivo studies. Several ectopic receptors such as GIP, β-adrenergic receptors, vasopressin (V2-V3-vasopressin receptor), serotonin (5-HT7 receptors), and angiotensin II receptors, and increased expression or altered activity of eutopic receptors including the V1-vasopressin receptors, LH/hCG receptors, serotonin (5-HT4 receptor), and leptin receptors was found [5].

In our patient, the serum cortisol level was increased by ACTH stimulation, exogenous AVP, and isoproterenol. Because exogenous AVP could naturally stimulate ACTH and increase serum cortisol levels, we checked serum ACTH levels during an AVP stimulation test. His serum cortisol level was increased by 82%, and serum ACTH level was increased by 11.5%. We were unable to confirm if AVP itself stimulated the adrenal cortex directly, or whether the induced ACTH caused cortisol secretion. A postural test was performed to screen for the aberrant expression of the AVP, β-adrenergic, or angiotensin II receptors. Interestingly, cortisol secretion was stimulated by exogenous AVP and a β-adrenergic agonist; however, a postural test failed to stimulate cortisol secretion. We repeated the postural test, and also checked the patient's aldosterone level to verify if the test was accurate and determined serum ADH levels to confirm if endogenous ADH stimulated adrenal cortisol secretion. Because serum aldosterone levels increase in response to postural stimulation, the test itself was working; however, the cortisol response was negative. This suggests that the patient's β-adrenergic receptor showed a blunted response to the test. Because we did not determine the serum catecholamine levels during postural stimulation, it was unclear whether the postural test induced sufficient endogenous catecholamine. Although a stronger stimulus (such as a treadmill test) would have induced endogenous catecholamine and increased serum cortisol levels, the patient refused because he had ischemic heart disease. In our case, exogenous AVP, but not endogenous ADH, stimulated adrenal cortisol secretion. This suggests that the cortisol response to exogenous pharmacological levels of vasopressin was mediated by AVP-induced catecholamine release [3]. We finally concluded that this patient had ectopic β-adrenergic receptors on the adrenal cortex, and recommended long-term propranolol therapy. However, because he strongly desired to undergo treatment with a rapid response, we consulted the Urological Department who recommended bilateral adrenalectomy.

The identification of aberrant adrenal hormone receptors in AIMAH provides novel opportunities for specific pharmacological therapies as alternatives to adrenalectomy. In 1997, Lacroix et al. [3] reported the use of propranolol therapy for ectopic β-adrenergic receptors in adrenal Cushing syndrome in 1997. Some studies have revealed aberrant receptor expression in vitro using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. However, a limitation of our study is that we did not confirm aberrant receptor expression using in vitro analyses. In conclusion, we report a rare case of an AIMAH patient. In vivo examinations suggested that altered cortisol regulation due to a β-adrenergic agonist was involved in the pathogenesis of the AIMAH patient.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.