Native valve endocarditis due to extended spectrum β-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae

Article information

To the Editor,

Klebsiella species are common pathogens that cause community-onset and hospital-acquired pneumonia, intra-abdominal infections, and bloodstream infections. Infective endocarditis due to Klebsiella species is rare, accounting for less than 1% of cases, and is frequently accompanied by complications and a high in-hospital mortality rate [1]. Moreover, with the emergence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae, endocarditis due to ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumonia (ESBL-KP) is of concern due to the limited treatment options and notoriously high morbidity and mortality. Hospitalization is a significant risk factor for bloodstream infections due to ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae, but no cases of health-care-associated native valve endocarditis caused by ESBL-KP have been reported. Here, we report a case of health-care-associated infective endocarditis due to ESBL-KP with multiple metastatic infectious complications, and discuss the optimal treatment strategies.

A 70-year-old male was admitted to the hospital because of persisting fever. Forty-seven days prior, he had been at another hospital for 10 days with a common bile duct stone. A percutaneous biliary drainage tube was inserted followed by a percutaneous stone removal procedure. Twenty days after discharge, he was readmitted to that hospital with a fever and chills. Initial blood and urine cultures grew ESBL-KP, confirmed using a commercial automated system (Microscan, Dade Behring, West Sacramento, CA, USA). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of that isolate against several antibiotics were as follows: cefepime > 16; ciprofloxacin > 2; gentamicin ≤ 1; amikacin = 8; tobramycin > 8; piperacillin/tazobactam ≤ 8; imipenem ≤ 4; meropenem ≤ 4.

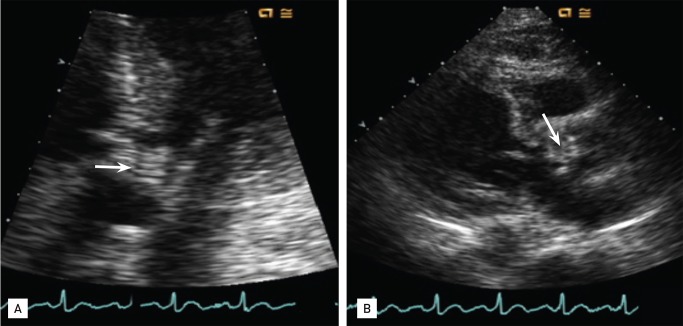

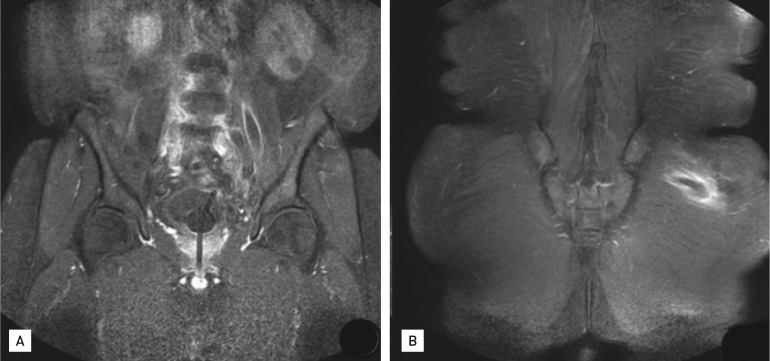

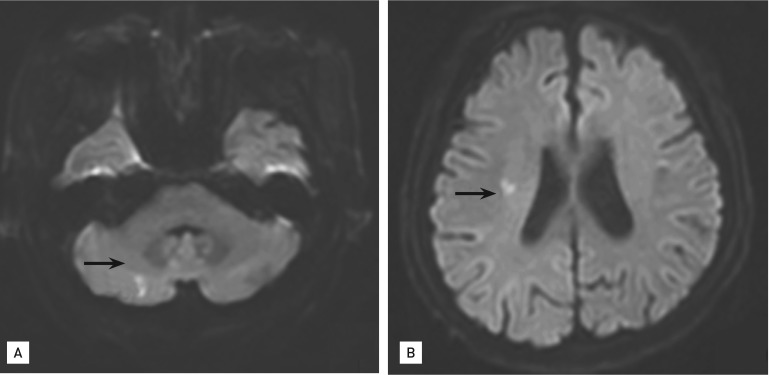

On hospital day 3, imipenem/cilastatin was administered intravenously, but the fever persisted and a cardiac murmur was detected on hospital day 8. The patient also complained of severe pain in the left lower back and the left side of the pelvis. An echocardiogram revealed a 1.0 × 1.2-cm vegetation on the aortic valve (Fig. 1). ESBL-KP was detected again in one set of peripheral blood cultures on hospital day 8. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed abscesses in the left psoas and gluteus maximus and spondylodiscitis in the L4-S1 spine with paraspinal abscess formation (Fig. 2). On hospital day 11, he developed septic shock, necessitating mechanical ventilation and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) for 2 days, and imipenem was changed to meropenem. On hospital day 13, the vasopressor, ventilator and CRRT were stopped, and blood cultures showed negative conversion. On hospital day 17, he was transferred to our hospital for further management. On examination, he was still febrile with a body temperature of 38.3℃, a blood pressure of 134/54 mmHg, a pulse of 105 beats per minute, and a respiration rate of 22 breaths per minute. He was disoriented, and a brain MRI revealed acute embolic infarctions in the bilateral frontal, right-sided splenium and cerebellum (Fig. 3). Ten days after admission to our hospital, the patient underwent aortic valve replacement surgery. Vegetations were identified on the aortic valve and tricuspid valve. Gram stain and culture of the surgical tissues yielded no microorganisms. The patient's fever resolved 2 days after surgery; however, he developed a postoperative sternotomy site infection caused by Candida albicans, which was successfully treated with incision and debridement surgery, and intravenous fluconazole for 6 weeks. On hospital day 53, the meropenem was changed to ertapenem because it could be administered once per day. A transthoracic echocardiogram obtained 7 days after surgery showed good cardiac valve function with no residual valvular lesions.

Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging. (A) Abscesses in the left psoas muscle and (B) left gluteus maximus muscle.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (diffusion weighted image): acute embolic infarctions in cerebellum (A) and right side splenium (B).

The abscesses had disappeared and the spondylitis had improved on spinal MRI performed on hospital day 88. The patient was transferred back to the secondary-care hospital and continued to receive ertapenem for 50 days. After a total of 18 weeks of intravenous carbapenem therapy, he was discharged without any significant residual comorbidities.

With the worldwide emergence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae over the past two decades, infections caused by ESBL-KP have received significant attention. ESBL-KP can cause a variety of infections, but a case of health care-associated native valve endocarditis caused by ESBL-KP has not been reported previously. In a large prospective cohort study, ESBL-KP infective endocarditis accounted for five of 2,761 cases (0.2%) of definite endocarditis [1]. Among these five cases of Klebsiella endocarditis, complications were noted in two (40%), surgery was needed in two (40%), and the in-hospital mortality rate was 40% (two cases). In the study by Anderson and Janoff [2], K. pneumoniae accounted for 1.2% of native valve endocarditis and 4.1% of prosthetic valve endocarditis. Because of its rarity, the exact incidence and clinical features of Klebsiella endocarditis have yet to be characterized. Klebsiella species adhere poorly to cardiac valves compared with other organisms, such as Enterococci, viridans Streptococci, Staphylococci, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which could explain the rarity of Klebsiella endocarditis [3]. Furthermore, only two cases of infective endocarditis caused by ESBL-KP have been reported to date. One was a case of prosthetic valve endocarditis and the other was nosocomial endocarditis [2].

Our case was particularly interesting in that it was health-care-associated. A recent report indicated that the clinical characterization of health-care-associated infective endocarditis is associated with older age, diabetes, renal impairment, heart failure, and infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus [4]. Neither non-HACEK gram-negative bacilli (GNB) nor ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae were significant in that study. However, we believe that non-HACEK GNB including ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae should be considered in cases of health-care-associated infective endocarditis, especially in patients at high risk for GNB infections. Our patient may have acquired ESBL-KP during the previous admission when he underwent biliary procedures.

The known risk factors for ESBL-KP infections are defined based on a nosocomial setting, and risk factors for health care-associated acquisition of ESBL-KP have not been established. Further research is required to determine whether ESBL-KP infection is associated with a healthcare setting. However, based on previous studies of ESBL E. coli and health-care-associated infections, we can infer ESBL-KP is likely to be a causative microorganism.

The treatment for infective endocarditis caused by ESBL-KP has not been determined. Usually these patients require surgery combined with prolonged courses of antibiotics. At present, carbapenems are the treatment of choice. In a report by Zimhony [5], despite the low MIC of ciprofloxacin and piperacillin/tazobactam, therapy with ciprofloxacin followed by piperacillin/tazobactam failed because of the inoculum effect and induction of resistance. Ultimately, the infected prosthetic valve had to be replaced and the patient was treated for an additional 6 weeks with carbapenem plus amikacin after surgery. Our patient experienced a similar disease course. Although he was on appropriate antibiotics (carbapenem), he had persistent fever, developed metastatic infections, and needed valvular surgery on day 26 of antibiotic therapy. After surgery, the patient's condition improved and we administered an additional 14 weeks of carbapenem therapy until the spondylitis and paravertebral abscess improved. A combination of aminoglycosides for Klebsiella endocarditis has been suggested in the literature, but reports of clinical experience with combination therapy are scarce. We treated our patient with carbapenem monotherapy successfully.

The limitation of this report is that we could not perform a confirmatory ESBL test because the isolate was not available. However, the sensitivity and specificity of ESBL detection by Microscan are 100% and 96.6%, respectively. The isolate was resistant to third-generation cephalosporins. The fact that the isolate was resistant to all β-lactam agents including third-generation cephalosporins supports ESBL production.

This is to our knowledge the first reported case of health-care-associated native valve endocarditis caused by ESBL-KP with multiple septic complications. The patient was successfully treated with valve replacement surgery and carbapenem monotherapy. Given the recent increase in the incidence of infections caused by ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae, clinicians should be aware of the potential for ESBL producers when managing health-care-associated infective endocarditis.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.