Successful treatment of enteropathy associated with common variable immunodeficiency

Article information

To the Editor,

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is a primary immunodeficiency characterized by defective B-cell differentiation and impaired immunoglobulin production [1]. CVID occurs equally in both sexes and usually presents in the second or third decade of life. Its prevalence is estimated to be between 1:50,000 and 1:200,000 individuals in the general population. Genetic defects that predispose to CVID have been identified in about 10% of affected patients [1]. The pathogenesis of CVID is complex, involving defects in both humoral and cellular immunity. B-cell maturation is abnormal, and impaired somatic hypermutation and a lack of isotype-switched memory B-cells have been demonstrated [1,2]. The diagnosis of CVID is based on decreased serum immunoglobulins and a failure to produce antibodies in response to vaccinations or infections. Other studies of B- and T-cell populations and subpopulations have been useful for defining the prognosis and risk of complications [1].

CVID has variable clinical manifestations, the most common being recurrent bacterial infections. Besides infections, CVID patients have an increased tendency to develop autoimmune disorders, lymphoproliferative disease, and malignancy [1,2]. Approximately half of untreated CVID patients have gastrointestinal manifestations including bloating, diarrhea, and malabsorption; in 5% of cases, these symptoms are severe and associated with histological evidence of mucosal inflammation [3]. Because the gastrointestinal tract is the largest lymphoid organ in the body, intestinal manifestations are expected to be common. These gastrointestinal conditions can be classified into four groups: infection, malignancy, inflammatory, and autoimmune [4]. The gastrointestinal tracts display a wide spectrum of histologic patterns. The mucosa shows increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, villous blunting, nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, crypt distortion, overexpression of apoptosis, and paucity of plasma cells [5].

The mainstay of treatment for CVID is replacement of immunoglobulins and control of infectious disease. However, the management of CVID enteropathy has been unsatisfactory. The T-cell mediated defects and autoimmune phenomenon are thought to be the causes of CVID enteropathy [3,4]. Therefore, immunoglobulins alone may be ineffective. Given the poor understanding of its pathophysiology, few therapeutic options are available for enteropathy in patients with CVID. Some studies have shown that corticosteroids improve diarrhea in these patients [4]. Corticosteroids inhibit the immune inflammatory response partly through their effects on T-cells; however, considerable systemic side effects limit their use. Combination therapy with steroids and immunomodulators such as azathioprine can be used, but the efficacy and tolerability of such combination therapy are not well documented [4].

We report herein a patient with CVID who presented with chronic diarrhea and severe weight loss treated with immunoglobulins, corticosteroids, and azathioprine.

A 24-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for evaluation and treatment of diarrhea and weight loss. She had a 6-month history of episodes of diarrhea five to six times a day; it was watery to semisolid without mucus or blood and was associated with the passage of undigested food materials. She had lost 15 kg of body weight despite a good appetite. Exhaustive evaluations at different hospitals were unrevealing. She received several courses of antibiotics, but her symptoms did not resolve. Her medical history included recurrent episodes of sinusitis, otitis media, pneumonia, and pyelonephritis since childhood. Her family history was unremarkable.

On admission, her blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg, temperature was 36℃, and pulse was 70 beats per minute. Her height was 159 cm and weight was 33 kg (body mass index, 13.05). On chest auscultation, inspiratory crackles were heard in the upper lung fields. Abdominal examination revealed neither masses nor tenderness to palpation.

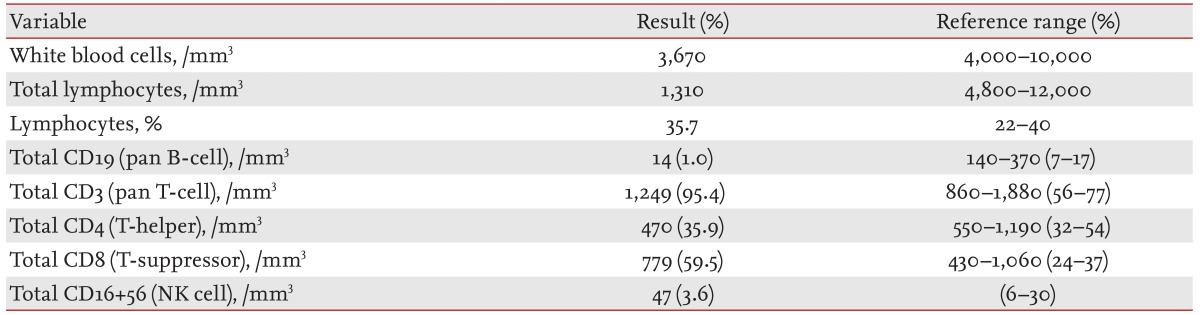

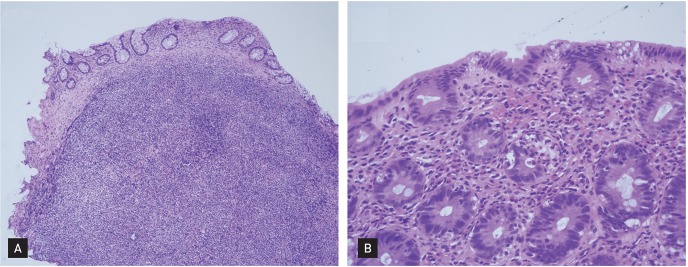

Routine blood tests revealed a hemoglobin level of 10.8 g/dL, white blood cell count of 5,790/mm3, platelet count of 132,000/mm3, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 2 mm/hr. Blood chemistry testing showed a total protein level of 5.8 g/dL, albumin level of 4.0 g/dL, globulin level of 1.8 g/dL, aspartate aminotransferase level of 27 IU/L, alanine transaminase level of 20 IU/L, creatinine level of 0.5 mg/dL, glucose level of 103 mg/dL, amylase level of 59 IU/L, and lipase level of 57 IU/L. Antibodies against syphilis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus were not detected. Antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and isohemagglutinin were negative. Adrenal and thyroid function study results were normal. The quantitative immunoglobulin levels were IgG 351 mg/dL (normal range, 700 to 1,600); IgA 37 mg/dL (normal range, 70 to 400); and IgM 57 mg/dL (normal range, 40 to 230). The results of flow cytometric lymphocyte subset analysis are shown in Table 1. Urinalysis was negative for occult blood or protein. Stool examination for bacterial cultures and parasites was also negative. Abdominal computed tomography revealed mild splenomegaly. Gastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy findings were visually unremarkable. Random mucosal biopsies from the colon revealed increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, paucity of plasma cells, and apoptotic bodies in the crypts (Fig. 1). According to these findings, she was diagnosed with CVID. She began to receive therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin (400 mg/kg every 4 weeks). However, the diarrhea and bloating continued. A trial with corticosteroids (prednisone 10 mg/day) and azathioprine (75 mg/day) was attempted. With these therapies, the frequency of diarrhea decreased and the patient gradually regained weight.

Colonoscopic biopsy specimen shows (A) prominent lymphoid follicles indicating nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and variable villous blunting with crypt atrophy (H&E, ×100) and (B) increased lymphocyte infiltration, acute inflammation in the crypt epithelium, frequent apoptotic bodies, and a lack of plasma cells (H&E, ×400).

In summary, we have presented herein a case with CVID associated with enteropathy. This case illustrates one of the varied and uncommon presentations of CVID. Although these complications cause severe morbidity, the heterogeneity of such presentations induce delays in the diagnosis of CVID. In such patients with chronic diarrhea, CVID should be kept in mind as a possible cause.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.