Diabetic ketoacidosis as a presenting symptom of complicated pancreatic cancer

Article information

To the Editor,

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is an aggressive cancer; the tumor is localized and potentially curable in fewer than 20% of patients at diagnosis. Thus, the overall 5-year survival rate of pancreatic cancer is less than 5%. Several studies have found an increased incidence of pancreatic cancer in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM); however, other studies have shown that pancreatic cancer may cause glucose intolerance. Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a lethal complication of DM characterized by severe hyperglycemia and metabolic ketoacidosis caused by absolute or relative insulin def iciency. However, DKA is rarely an initial presenting symptom of complicated pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Here we present a case of pancreatic adenocarcinoma that manifested as DKA and its diagnosis was delayed because of a coexisting pancreatic abscess; additionally, we review the relevant literature.

A 36-year-old woman visited our emergency department complaining of dyspnea, fever, and abdominal discomfort. She had a history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) during her second pregnancy (6 years ago) and had no familial history of DM or malignancies including pancreatic cancer. She had no history of smoking or alcohol consumption. On arrival, her vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 130/80 mmHg, heart rate 130 per minute, respiration rate 32 per minute, and body temperature 38.6℃. Physical examination showed a soft and non-tender abdomen and no abnormal findings. Laboratory f indings were as follows: urinalysis (glucose [+++], ketone [++++], protein [+]), random serum glucose 334 mg/dL, arterial blood gas analysis (pH 7.1, HCO3 4.5 mmol/L, anion gap 17.6), serum osmolality 285 mOsm/kg, white blood cell count 27.95 (4.8-10.8)×103/µL, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein 204.27 [-5] mg/L, aspartate aminotransferase 89 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 87 U/L, amylase 59 IU/L, lipase 109 U/L, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) 9.7%, insulin 6.8 (2.6-24.9) µIU/mL, C-peptide 1.13 (1.1-4.4) ng/mL, cancer antigen 19-9 30.36 (-37) U/mL.

Based on the high HbA1c level, low but relatively preserved insulin secretion, and previous history of GDM, the patient was diagnosed as type 2 DM. However, the sudden onset of DKA is unusual in patients with type 2 DM, and high fever is not a sign of DKA [1]. Thus, we performed further diagnostic evaluations to determine the predisposing factors. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a massive retroperitoneal abscess originating from the pancreas (Fig. 1A). The abscess had multifocal air fluid levels and had invaded adjacent structures such as the small intestine and posterior surface of the stomach. In accordance with the examination results, our initial diagnosis was DKA precipitated by pancreatic abscess in a newly diagnosed type 2 DM. Fluid therapy and intravenous insulin infusion with empirical antibiotics were administered and ultrasound guided drainage was performed by percutaneous tube. The cytology finding was compatible with the presence of an abscess, and Klebsiella pneumoniae was identified in the abscess. The patient's condition did not improve following these interventions, and we made the decision to perform an exploratory laparotomy. During surgery we performed a partial resection of the pancreas with debridement of the necrotic tissue because the frozen biopsy showed nonspecific chronic inf lammation. The postoperative pathological diagnosis was chronic pancreatitis with fibrosis (Fig. 1B). After internal and external drainage, the patient was discharged and multiple insulin injections were continued for glucose control. At follow-up, the abdominal CT scan revealed that the abscess had increased in size (Fig. 2A), and her general condition had not improved. We reoperated on the pancreatic mass and confirmed the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma complicated by a pancreas abscess (Fig. 2B and 2C). Following the surgery, the patient was treated with palliative chemotherapy and died 6 months after her first visit to our emergency department.

(A) Abdominal computed tomography scan showing a massive, multifocal air filled abscess originating from the pancreas expanding into the retropancreatic space with invasion of adjacent structures such as the small intestine and posterior aspect of the stomach. (B) Pathological appearance of the pancreas at the first admission. The pathology of the first operative specimen revealed chronic inflammatory cells around the pancreatic duct with interlobular and perilobular fibrosis (H&E, × 100).

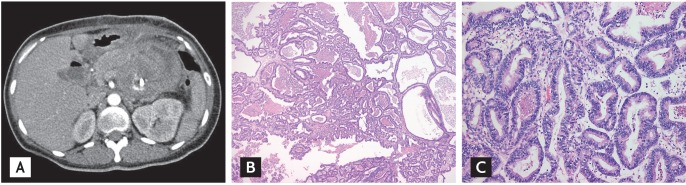

(A) Abdominal computer tomography scan of the reoperative specimen. Although the air filled abscess lesion was drained, the mass continued to grow and expand into the adjunct structures. (B) Low power microscopic view of the reoperative specimen showing tumor cells of variable size with a tubular, papillary pattern (H&E, × 40). (C) High power microscopic view showing tumor cells with a tubular growth pattern and focal infiltration (H&E, × 200). The tumor cells had a columnar shape with a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei.

Among adult patients presenting with DKA, 47% had known type 1 DM, 26% had known type 2 DM, and 27% had newly diagnosed DM. Precipitating factors in the development of DKA are infections, intercurrent illnesses, psychological stress, and poor compliance with therapy. Infection is the most common precipitating factor for DKA, occurring in 30% to 50% of cases. Other acute conditions that may precipitate DKA include cerebrovascular accident, alcohol or drug abuse, pancreatitis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, and trauma. However, a significant overlap exists between the clinical presentation of acute pancreatitis and DKA, which may make the diagnosis of pancreatitis in DKA difficult and potentially overlooked [2]. Furthermore, acute pancreatitis is more likely to be associated with severe DKA with marked acidosis. Thus, it is likely that both DKA and the pancreatic abscess contributed to the development of metabolic acidosis in our patient.

DKA has been documented as a presenting symptom of a pancreatic tumor only in endocrine tumors such as glucagon-secreting islet cell neoplasm or somatostatinomas, which are rare conditions. Furthermore, DKA associated with a pancreatic adenocarcinoma is very rare and only one case has been reported previously: the patient, who had a long-standing history of type 2 DM, presented with DKA and was found to have a pancreatic adenocarcinoma [3]. However, DKA as an initial presenting symptom of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in patients without DM is extremely rare. Approximately 80% of patients with pancreatic cancer have glucose intolerance or f lank diabetes; however, evidence for a cause and effect relationship between DM and pancreatic cancer is inconclusive. Although prolonged hyperinsulinemia has been suggested to stimulate pancreatic carcinogenesis [4], a meta-analysis that included 36 clinical trials of patients with type 2 DM showed that diabetes is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer [5]. Currently, considerable experimental and epidemiological evidence supports both arguments. Thus, further studies are necessary to clarify the relationship between DM and pancreatic cancer.

In general, the classical presentation of an adenocarcinoma of the pancreas includes one or more of the following symptoms: obstructive jaundice, dark urine, weight loss, and deep-seated abdominal pain. However, the early symptoms of pancreatic cancer are nonspecific, and associated symptoms may occur later in the disease progression; thus, most pancreatic cancers are diagnosed in the advanced stage. Previous reports have documented that pancreatic carcinomas may coexist with complications such as acute pancreatitis, a pancreatic pseudocyst, and pancreatic abscess. Thus, a carcinoma may present as a septic complication of pancreatitis such as an infected pseudocyst, pancreatic abscess, or infected pancreatic necrosis, although this situation is exceedingly rare because the pancreatitis associated with pancreatic cancer is usually mild. Thus, the diagnosis of a complicated pancreatic adenocarcinoma is likely to be delayed unless the physician has a high index of suspicion.

In summary, we report here a patient with undiagnosed type 2 DM presenting as DKA resulting from a massive pancreatic abscess. The initial operative biopsy revealed chronic inf lammatory cells associated with extensive inflammation and necrosis of pancreatic tissues. Although this clinical situation is unusual, physicians should not overlook the possibility of pancreatic cancer in newly detected type 2 DM presenting with DKA, particularly when obvious precipitating factors are not present. Furthermore, the fact that pancreatic cancer can coexist with complicated pancreatitis should be taken into consideration. Despite numerous investigations, the relationship between pancreatic cancer and DM is not clear, highlighting the need for further study.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.