A case of primary aldosteronism presenting as non-ST elevation myocardial infarction

Article information

To the Editor,

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is associated with several cardiovascular diseases. Postulated mechanisms include inappropriate volume retention, suppression of endothelial function, and target organ inflammation and fibrosis. While heart failure in conjunction with arrhythmias is the most common cardiovascular complication in PA, few cases of coronary artery disease (CAD) in concurrence with PA have been reported [1-3]. Here, we propose a possible mechanism for CAD developing in PA based on a case of PA presenting as non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) in the absence of heart failure or other comorbidities in a relatively young Korean male. To our knowledge, this is the first report of PA presenting with NSTEMI.

A 43-year-old male with a 10-year history of treatment-resistant hypertension presented to the cardiology outpatient clinic with stabbing chest pain in the retrosternal area. The pain began at rest and lasted for a few seconds to a few minutes. To treat his hypertension, he was taking carvedilol 25 mg, telmisartan 80 mg, and spironolactone 25 mg. He had a 20 pack-years smoking history, but no family history of cardiovascular disease. He was admitted for further investigations.

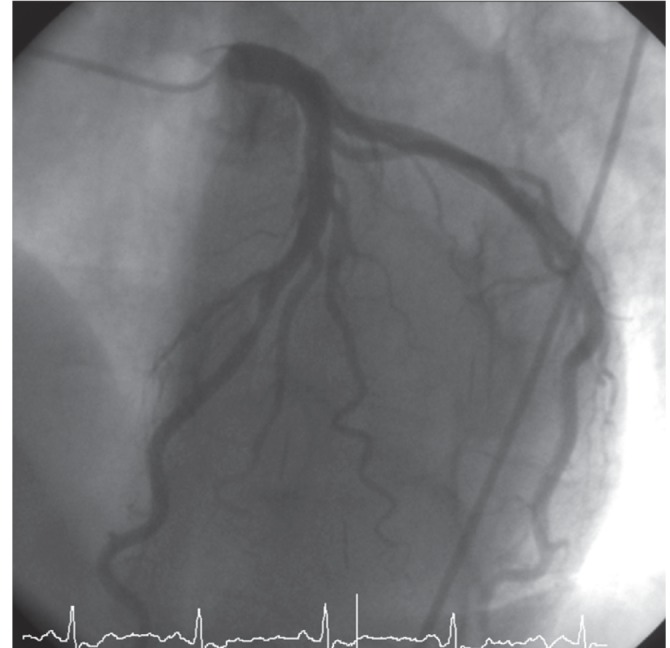

On admission, his blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg, pulse 66 per minute, body temperature 36℃, respiration rate 20 per minute, and body mass index 23.0 kg/m2. The initial laboratory testing yielded serum sodium 144 mmol/L, potassium 2.7 mmol/L, chloride 101 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL, creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, troponin-I 0.16 ng/mL, creatine kinase 78 U/L, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) 1.81 mg/L, and creatinine kinase-MB 1.9 ng/mL. The lipid profile, liver function tests, and complete blood count with differential were all within normal limits. The chest X-ray was unremarkable and the initial electrocardiograph (ECG) showed a prominent U wave in all precordial leads and T wave inversion in V3 to 5. Echocardiography revealed a normal ejection fraction (70%) with no valvular abnormality. The right and left carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) was 0.6 and 0.5 mm, respectively, without visible plaque. The brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD), pulse wave velocity (PWV), ankle-brachial index (ABI) bilaterally, and cardioankle vascular index (CAVI) bilaterally were all normal. Based on these findings, NSTEMI was diagnosed and followed by coronary angiography with successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with a drug-eluting stent at the mid-left anterior descending artery (Fig. 1).

Coronary angiography demonstrating 75% diameter stenosis of the mid-left anterior descending artery.

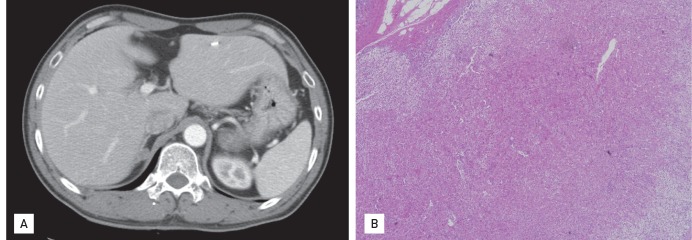

After PCI, his serum potassium and blood pressure remained uncorrected despite oral potassium supplementation and three antihypertensive medications. In light of his uncorrected electrolyte and blood pressure, additional endocrinological tests were performed. His thyroid-stimulating hormone level was 2.46 µU/mL, free T4 1.36 ng/dL, T3 143 ng/dL, 24-hour urine free cortisol 71 µg/day, urine vanillylmandelic acid 2.0 mg/day, urine norepinephrine 118.2 µg/day, urine epinephrine 11 ng/day, urine metanephrine 0.4 mg/day plasma norepinephrine 0.28 ng/mL, plasma epinephrine 0.04 ng/mL, plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone 65.2 pg/mL at 8:00 AM and 22.8 pg/mL at 4:00 PM, plasma cortisol 21.2 µg/dL (585.12 nmol/L) at 8:00 AM, 9.4 µg/dL (259.44 nmol/L) at 4:00 PM, and 15.6 µg/dL (430.56 nmol/L) at midnight, plasma aldosterone 1,080.3 pmol/L (cutoff value > 450 pmol/L), plasma renin activity (PRA) 0.1 ng/mL/hr, and aldosterone-renin ratio 10,803 pmol/L:ng/mL/hr (cutoff value > 750 pmol/L:ng/mL/hr). To avoid misinterpretation of the plasma cortisol level during a stressful condition (i.e., NSTEMI), we checked the serum cortisol level several times during the following 6 months and confirmed a consistently elevated level. Suspecting PA, abdominal computed tomography revealed a 1.4 × 1.2-cm mass at the right adrenal gland (Fig. 2A). After discontinuing all antihypertensive drugs, he underwent the furosemide loading test, which showed no response. Based on the high 24-hour urine free cortisol level, an overnight dexamethasone suppression test (DST) was done. After a 1-mg dose DST, the plasma cortisol level was 2.2 µg/dL. Subsequently, a low-dose DST was performed, but the result was negative. Hence, we could rule out Cushing syndrome.

(A) Abdominal computed tomography showing an adrenal adenoma of the right adrenal gland, medial limb. (B) Histopathology confirming adrenocortical adenoma (light microscopy, H&E, × 200).

The adrenal adenoma was removed laparoscopically; the specimen showed a cortical adenoma with primarily cortical hypertrophy mixed with regions of partial cortical atrophy, suggesting autonomous cortisol secretion (Fig. 2B). Postoperatively, his blood pressure, serum potassium level, and ECG normalized.

The chronically elevated serum aldosterone level in patients with PA makes them susceptible to a wide spectrum of cardiovascular diseases, from arrhythmias to congestive heart failure and CAD. The relatively high incidence of heart failure in conjunction with arrhythmias in patients with PA can be explained by left ventricular hypertrophy due to hypertension, hypokalemia, and cardiac fibrosis due to aldosterone excess [1-3]. Although many have hypothesized that aldosterone plays a role in the development of CAD, the number of cases of PA occurring in concurrence with CAD remains very small, especially in Asian populations. Although Nakajima et al. [4] reported a myocardial infarction occurring in PA and Nishimura et al. [2] stable angina in PA, these patients were elderly, leaving room for discussion as to whether age along with other comorbidities associated with senility contributed to the outcome [1]. The reasons for the obvious discrepancy in the incidence of heart failure and CAD have never been explored nor has the exact mechanism underlying the development of CAD in PA been established.

This case is interesting in terms of the pathophysiological role of aldosterone in the development of NSTEMI in a relatively young patient with no risk factors for CAD other than smoking. It is also notable that despite the long history of treatment-resistant hypertension, there were no signs of endothelial dysfunction or arterial stiffness, evident by the normal FMD, PWV, ABI, CAVI, hs-CRP, and carotid IMT. The atherosclerotic lesions were limited to the coronary artery. In addition, the fact that his NSTEMI was diagnosed before the diagnosis of PA makes this case unique. It appears that the lack of symptoms owing to hypokalemia, muscle weakness, and constipation delayed the detection of the PA.

We would like to highlight that this NSTEMI occurred in the absence of left ventricular dysfunction, suggesting that a separate mechanism exists for the development of CAD. Although we were not able to prove it, after reviewing various studies, we suggest the autonomous secretion of cortisol in association with PA as the culprit. Recent studies support the strong correlation between the autonomous secretion of cortisol and the increase in cardiovascular events [4]. This patient had an elevated midnight cortisol, an initial 24-hour urine cortisol > 50 µg/day, and a plasma cortisol level after 1-mg DST > 2.0 µg/dL; all suggest subclinical hypercortisolism. Hypercortisolism is associated with the decreased production of vasodilators, such as nitric oxide (NO), in coronary artery endothelial cells, and this might lead to the development of CAD. Rogers et al. [5] suggested the following as the mechanism of NO synthesis downregulation: 1) decreased endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) mRNA expression, 2) increased degradation of eNOS mRNA, 3) decreased eNOS protein stability, and 4) decreased agonist-mediated intracellular calcium mobilization. Such changes inevitably lead to an increased risk of CAD developing. Although we did not demonstrate a relationship between hypercortisolism and NO production in this case, it is safe to say that this case, at least, corroborates the role of cortisol in the development of coronary events.

Another possible mechanism might be that chronic aldosterone excess alters the normal immune response system by activating proinflammatory mediators such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, interleukin-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and matrix metalloproteinases, thereby setting a proinflammatory vascular phenotype and plaque vulnerability [3]. This inflammatory and endothelial dysfunction might be responsible for the development of CAD in PA patients.

In conclusion, measuring serum cortisol level might help to predict CAD development in patients with PA. In addition, in CAD patients without typical risk factors, secondary endocrine causes should be suspected.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.