Acute Viral Myopericarditis Presenting as a Transient Effusive-Constrictive Pericarditis Caused by Coinfection with Coxsackieviruses A4 and B3

Article information

Abstract

Acute myopericarditis is usually caused by viral infections, and the most common cause of viral myopericarditis is coxsackieviruses. Diagnosis of myopericarditis is made based on clinical manifestations of myocardial (such as myocardial dysfunction and elevated serum cardiac enzyme levels) and pericardial (such as inflammatory pericardial effusion) involvement. Although endomyocardial biopsy is the gold standard for the confirmation of viral infection, serologic tests can be helpful. Conservative management is the mainstay of treatment in acute myopericarditis. We report here a case of a 24-year-old man with acute myopericarditis who presented with transient effusive-constrictive pericarditis. Echocardiography showed transient pericardial effusion with constrictive physiology and global regional wall motion abnormalities of the left ventricle. The patient also had an elevated serum troponin I level. A computed tomogram of the chest showed pericardial and pleural effusion, which resolved after 2 weeks of supportive treatment. Serologic testing revealed coxsackievirus A4 and B3 coinfection. The patient received conservative medical treatment, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and he recovered completely with no complications.

INTRODUCTION

Acute myocarditis is an acute inflammatory disorder that primarily involves the myocardium. It can be caused by various drugs, systemic diseases, toxins, and infections, although viral infection is the most common etiology [1]. Acute pericarditis is often accompanied by some degree of myocarditis, although these two entities are not always associated. In clinical practice, pericarditis and myocarditis coexist because they share common etiologic agents, mainly cardiotropic viruses such as coxsackieviruses [2,3]. Effusive-constrictive pericarditis is a clinical hemodynamic syndrome in which constriction of the heart by the visceral pericardium occurs in the presence of tense effusion in a free pericardial space [4].

Diagnosing and managing acute myopericarditis at an early stage is important, but difficult, since it mimics acute myocardial infarction and its natural course is markedly heterogeneous, ranging from self-limiting to cardiopulmonary collapse or death. Few reports have described acute myopericarditis presenting as transient effusive-constrictive pericarditis and mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Thus, we report here a case of acute viral myopericarditis presenting as transient effusive-constrictive pericarditis and caused by coinfection with coxsackieviruses A4 and B3.

CASE REPORT

A 24-year-old man presented to the emergency department with chest pain, nausea, shortness of breath, and general weakness. The patient mentioned having flu-like symptoms 2 weeks prior to presentation. He had no significant past medical history or family history. He had a heart rate of 150 beats/min, blood pressure of 85/60 mmHg, respiratory rate of 22 breaths/min, and body temperature of 36.4℃.

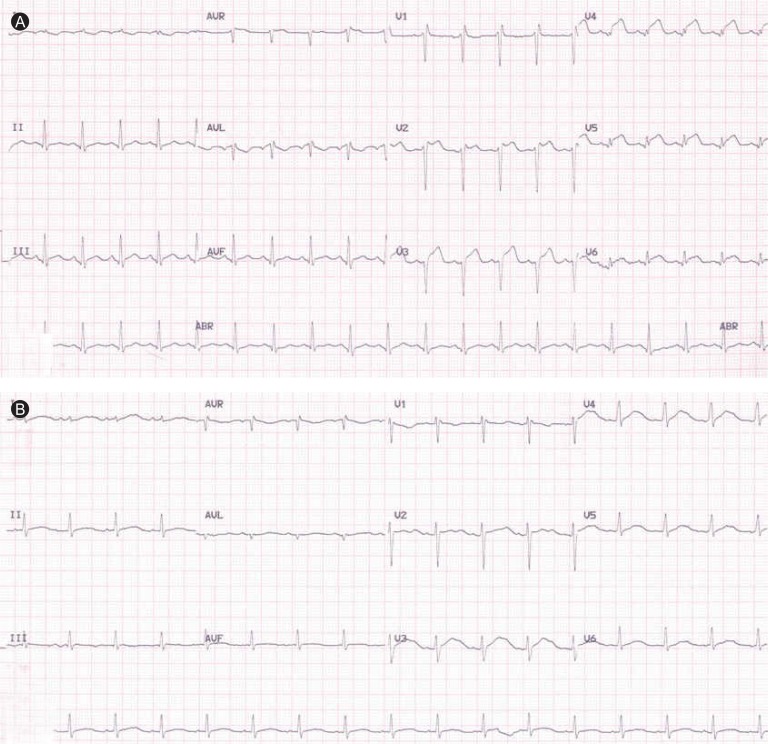

Initial laboratory findings revealed a white blood cell count of 14,530/mm3, a hemoglobin level of 16.3 g/dL, and a platelet count of 168,000/mm3. Cardiac enzyme findings were as follows: creatinine kinase (CK) 256 IU/L (reference range, 0 to 190), CK-MB 16.32 ng/mL (reference range, 0 to 5), and troponin I 10.16 ng/mL (reference range, 0 to 0.78). The B-type natriuretic peptide level was elevated at 190.48 pg/mL (reference range, 2 to 100). The initial electrocardiogram showed ST segment elevation in V2-V6 (Fig. 1A). Echocardiography showed global wall motion abnormalities and moderate systolic dysfunction (EF, 38%) in the left ventricle (LV), with a moderate amount of pericardial effusion (Fig. 2A). Echocardiography revealed constrictive physiology, such as septal bouncing, significant respiratory variation in the mitral inflow E wave (Fig. 2C), and increased diastolic flow reversal in the hepatic vein on expiration (Fig. 2D). Initial chest X-ray and chest computed tomography (CT) showed pericardial and bilateral pleural effusions (Fig. 3A). Ultrasound-guided aspiration of the pleural effusion revealed a transudate. Coronary angiography was normal. Tests for Epstein-Barr virus IgM, cytomegalovirus IgM, herpes simplex virus IgM, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, and anti-dsDNA were all negative. However, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay serologic antibody tests for coxsackievirus revealed a high serum titer (> 1:32) of serotypes A4 and B3.

Initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showing ST segment elevation in the V2-V6 leads (A). Two weeks later, ECG had normalized (B).

Initial echocardiogram showing moderate pericardial effusion (A), abnormal septal motion and systolic dysfunction of the left ventricle (B), respiratory variation of the mitral inflow E wave (C), increased diastolic flow reversal with expiration in the hepatic vein (D), and plethora of the inferior vena cava (E). Tissue Doppler imaging of the septal mitral annulus indicated normal diastolic function (F).

Chest computed tomography (CT) showing pericardial and bilateral pleural effusions (A). Follow-up CT after 4 weeks indicated the disappearance of these effusions (B).

The patient received conservative treatment with ibuprofen, ramipril, and furosemide, and his cardiac enzymes and ST segment elevation normalized within 2 weeks (Fig. 1B). After 4 weeks, chest CT indicated disappearance of the pericardial and pleural effusions (Fig. 3B). Echocardiography showed disappearance of constrictive physiology and normalized LV systolic function without regional wall motion abnormalities (Fig. 4). Follow-up coxsackievirus A4 and B3 antibody titers had normalized after 6 months.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates acute myopericarditis with transient effusive-constrictive pericarditis caused by coinfection with coxsackieviruses A4 and B3. When considering acute myocarditis and acute pericarditis, physicians usually place clinical emphasis on one or the other diagnosis. However, acute myopericarditis must be distinguished from pericarditis since a diagnosis of myocarditis has greater prognostic significance than that of pericarditis. Myocarditis can lead to fatal complications, including ventricular arrhythmia, or cardiac dilatation and subsequent cardiac collapse. These complications can develop abruptly and rapidly become life-threatening [1,5].

Endomyocardial biopsy is not always required, as it is associated with certain procedural risks and offers limited benefits from a therapeutic perspective. Nevertheless, it remains the gold standard for diagnosing myocarditis [2]. We did not perform an invasive endomyocardial biopsy on our patient since he responded well to medical treatment. The limited sensitivity and specificity of this diagnostic test demonstrate that the accurate diagnosis of myocarditis should not be based on histopathologic findings alone.

Effusive-constrictive pericarditis is an uncommon clinical entity characterized by pericardial effusion with constrictive physiology. It is regarded as a form of subacute constrictive pericarditis. The effusion may be lobulated, concentric, or regional. Over time, the effusion may become organized and the pericardial layers may become thickened [6].

In some patients with acute constrictive pericarditis, however, the symptoms and constrictive physiologic features resolve with medical management alone, a phenomenon that was first reported in 1987 and has been designated transient constrictive pericarditis [7]; this occurs frequently in post-pericardiectomy patients. However, it is also seen postinfection or in the setting of uremia. A recent study of 212 patients who had echocardiographic findings of constrictive pericarditis showed that 17% of these patients had resolution of constrictive physiology on follow-up echocardiography, without the need for pericardiectomy. In a subset of 22 patients who were followed regularly during the course of their illness, resolution of the constrictive hemodynamic features occurred an average of 8.3 weeks after diagnosis [8]. In the present case, 4 weeks was required for transient constrictive hemodynamics to resolve based on echocardiographic follow-up studies.

Respiratory variations in the mitral inflow and central venous flow velocities can be diagnostic, even in patients without definite pericardial abnormalities [9]. Tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) is a relatively new and effective echocardiographic tool that can help in the clinical diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis. Incremental M-mode, 2D, and transmitral flow Doppler studies with TDI provide an overall sensitivity and specificity of 88.8% and 94.8%, respectively, for the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis [10].

Pericardiectomy is the gold standard for the treatment of recurrent or constrictive pericarditis [3]. However, in some patients, such as our own, constrictive pericarditis may resolve spontaneously or after treatment with anti-inflammatory agents such as those mentioned above. Our patient recovered without sequelae.

In conclusion, acute myopericarditis must be distinguished from acute pericarditis because of the possibility of rapid, life-threatening progression. Thus, early diagnosis and management are important. With that in mind, clinical examination and echocardiography are essential. If a patient presenting with acute viral myopericarditis has signs of transient effusive-constrictive pericarditis, then he or she can be treated with medical therapy and followed with serial echocardiographic examinations.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.