Effect of Glutathione Administration on Serum Levels of Reactive Oxygen Metabolites in Patients with Paraquat Intoxication: A Pilot Study

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Based on preliminary in vitro data from a previous study, we proposed that 50 mg/kg glutathione (GSH) would be adequate for suppressing reactive oxygen species in patients with acute paraquat (PQ) intoxication.

Methods

Serum levels of reactive oxygen metabolites (ROM) were measured before and after the administration of 50 mg/kg GSH to each of five patients with acute PQ intoxication.

Results

In one patient, extremely high pretreatment ROM levels began to decrease prior to GSH administration. However, in the remaining four cases, ROM levels did not change significantly prior to GSH administration. ROM levels decreased significantly after GSH administration in all cases. In two cases, ROM levels decreased below that observed in the general population; one of these patients died after a cardiac arrest at 3 hours after PQ ingestion, while the other represented the sole survivor of PQ intoxication observed in this study. In the survivor, ROM levels decreased during the first 8 hours of GSH treatment, and finally dropped below the mean ROM level observed in the general population.

Conclusions

Treatment with 50 mg/kg GSH significantly suppressed serum ROM levels in PQ-intoxicated patients. However, this dose was not sufficient to suppress ROM levels when the PQ concentration was extremely high.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, the benefits of natural antioxidant vitamins, such as vitamins C and E, and the antioxidant properties of green tea have been discussed in numerous articles [1,2]. However, limited evidence exists regarding the efficacy of antioxidants and the appropriate therapeutic dose in a clinical setting. The optimal dose for a medication is the median dose required to produce the desired effect with no unfavorable side effect, and it is often determined based on an analysis of the dose-response relationship specific to the drug. Generally, the effect produced by a drug varies with the concentration that is present at its site of action, and usually approaches a maximum value, beyond which a further increase in concentration produces no additional effect. Thus, the effective dose of an antioxidant is the dose at which the levels of harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) decrease, or the dose at which ROS are significantly suppressed at the site of action. ROS are formed primarily in cells; however, direct measurement of ROS formation in cells is very difficult in the clinical setting. Instead, several indirect methods have been developed to measure free radicals and their metabolites, such as malondialdehyde (MDA; the final product of lipid peroxidation) [3] and hydroperoxides (ROOH; intermediate products of lipid peroxidation) [4].

Paraquat (PQ; 1,1'-dimethyl-4,4'-bipyridium dichloride) is one of the most widely used herbicides worldwide. In humans, intentional or accidental ingestion of PQ is frequently fatal, because of the very rapid formation of very large amounts of ROS in the body [5]. Several methods for suppressing the toxicity of PQ have been attempted over the past 30 years. Unfortunately, most of these methods have not proven effective, with the outcome primarily determined by the degree of exposure to PQ. Because PQ intoxication is characterized ROS-mediated injury, intravenous antioxidant therapy may be useful to attenuate short-term ROS generation and thus mitigate acute PQ poisoning. We have reported previously that the antioxidant glutathione (GSH) effectively attenuates PQ-induced ROS generation in fibroblasts [6]. In a further study examining the kinetics of the GSH metabolites cysteine (Cys) and methionine (Met), we estimated that a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight GSH would be sufficient to suppress PQ-induced ROS generation by 50% [7]. The current study was carried out to determine whether 50 mg/kg GSH suppresses the generation of ROS in patients with acute PQ intoxication.

METHODS

Five patients with acute PQ intoxication were enrolled in this study, which was approved by the Investigational Review Board of Soonchunhyang Cheonan Hospital. All procedures were performed after obtaining informed consent from each patient.

The control case was a 39-year-old man who was admitted to the ER 2 hours after the ingestion of 30 mg of diazepam (Valium®). Special permission was given to enroll this patient as a control. The patient received no antioxidant treatment and was discharged from hospital on day 3 without specific complaints.

All of the PQ intoxication patients arrived at the hospital within 3 hours after the intentional ingestion of the poison. They were admitted to the Institute of Pesticide Poisoning, Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital, between January and September 2009.

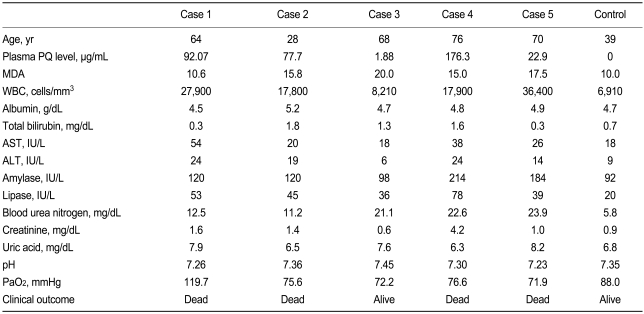

Baseline laboratory findings for cases 1 to 5 are summarized in Table 1. In addition, a mean value for serum reactive oxygen metabolites (ROM) in the general population was obtained from 60 healthy adults between 30 and 60 years of age.

Standard medical emergency procedures were followed. Briefly, gastric lavage was performed on all subjects who presented to the emergency room (ER) within 2 hours of PQ ingestion. Patients who presented to the ER more than 2 hours after PQ ingestion were given 100 g of Fuller's earth in 200 mL of 20% mannitol. Hemoperfusion was performed on patients showing positive urinary PQ tests upon arrival at the ER. Intravenous administration of GSH (50 mg/kg body weight) was started 1 hour after the first blood sample was taken and continued over the next 12 hours.

The amount of PQ ingested was estimated based on the number of swallows reported by the patient (one mouthful was considered to be 20 mL). High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was performed 7 days after ingestion to detect damage to the lung, and an additional follow-up HRCT was performed 1 week later if any abnormality was detected. Survivors were defined as those patients who survived for more than 3 months after PQ ingestion, maintained stable vital signs, and did not report specific complaints.

Urinary PQ levels were measured semiquantitatively using the dithionite method, whereas plasma PQ levels were evaluated by high-performance liquid chromatography. MDA levels were measured using an assay kit (NWLSSTM, Northwest Life Science Specialties, Vancouver, Canada); this test is based on the reaction between MDA and thiobarbituric acid (TBA), which forms an MDA-(TBA)2 adduct that strongly absorbs at 532 nm.

ROMs (free radical-derived compounds) in serum were measured using a commercially available assay kit (d-ROM Test, Diacron International, Grosseto, Italy). The test is based on the capacity of iron to break down ROOH, forming alkoxyl (RO.) and peroxyl (ROO.) radicals; the quantity of these compounds is directly proportional to the quantity of the ROOH present in the sample. Thereafter, RO. and ROO. are chemically trapped by the chromogen substrate. The results of the d-ROM test are expressed in Carratelli units (CARR) according to the following formula: 1 CARR = (Abs/min) × F (a correction factor with an assigned value, according to the results obtained with the calibrator) = 0.08 mg H2O2/dL.

The initial blood sampling was performed upon the patient's arrival at the ER to determine baseline levels of MDA, complete blood count, blood chemistry, and ROM level. Additional blood samples were collected hourly until 8 hours after PQ ingestion. In cases 2, 3, and 4, an additional sample was obtained at 30 minutes after the first sample. Case 4 died very early on the first day, for which reason only four samples were collected from this patient. For the control (diazepam) case, blood samples were collected every 30 minutes for the first 2 hours, and then on the hour for an additional two more hours (Fig. 1).

Sequential changes in reactive oxygen metabolite (ROM) levels. The arrow indicates the initiation of intravenous glutathione (GSH) administration at 50 mg/kg body weight. The control case is a patient with diazepam intoxication. In case 3, the patient's serum ROM level decreased gradually to a value below that of the mean of the general population; this patient was the sole survivor of the five cases of paraquat intoxication. The three horizontal dotted lines indicate the mean serum ROM (± SD) of the age- and gender-matched general healthy population (290 ± 59 Carratelli units).

RESULTS

The mean ROM level (± SD) among the general population was 289.6 ± 58.8 CARR (range, 202 to 350). In the control case (diazepam ingestion), seven sequential measurements were used to calculate a mean ROM level of 272.7 ± 12.7 CARR (range, 255.0 to 289.0).

Case 1 was a 64-year-old man in whom hemoperfusion was initiated 1 hour after admission. He died 17 hours after PQ ingestion. His plasma PQ level was 92.1 µg/mL at 3 hours after PQ ingestion with an initial ROM level of 940 CARR. This level decreased to 733 CARR 1 hour later without GSH administration. The patient's ROM levels at 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours after the initiation of GSH administration were 624, 640, 586, and 517 CARR, respectively.

Case 2 was a 28-year-old man who was admitted to the ER 3 hours after ingesting four mouthfuls of PQ. Despite intensive therapy, he died 24 hours after PQ ingestion. His plasma PQ level was 77.7 µg/mL at 3 hours after PQ ingestion with an initial ROM level of 513 CARR. This level was stable for 1 hour (526 CARR at 30 minutes, 523 CARR at 60 minutes) until GSH administration. After GSH administration, ROM levels decreased, to 338 and 323 CARR at 1 and 2 hours post-administration, respectively, but then rebounded to 402 and 395 CARR at 3 and 4 hours post-administration, respectively.

Case 3 was a 68-year-old man who arrived at the ER 2 hours after ingesting one mouthful of PQ. The patient's plasma PQ level was 1.18 µg/mL at 2 hours after PQ ingestion with pre-GSH ROM levels of 450 CARR at baseline, 441 CARR 30 minutes later, and 427 CARR at 1 hour, and 426 CARR at 2 hours after PQ ingestion. The patient's ROM levels decreased to 332, 319, and 281 CARR at 3, 4, and 5 hours, respectively, after GSH administration. HRCT of the lungs was performed on day 7 after admission and showed no evidence of PQ-induced lung injury. The patient was discharged on day 8 without complaints. This case was the sole survivor of the PQ intoxication patients observed here.

Case 4 was a 76-year-old man who arrived at the ER 1 hour after ingesting 200 mL of PQ. He developed unstable vital signs (blood pressure 80/50 mmHg) and hypoxia 1 hour after starting hemoperfusion, and died 2 hours after PQ ingestion. The patient's plasma PQ level was 176.3 µg/mL at 1 hour after PQ ingestion, and his ROM levels were 555 CARR at baseline, 545 CARR 30 minutes later, and 534 CARR 1 hour later. The patient's ROM levels decreased further to 269 CARR at 1 hour after GSH administration.

Case 5 was a 70-year-old man who arrived at the ER 2 hours after ingesting four mouthfuls of PQ. He died 41 hours after PQ ingestion. His PQ level was 22.9 µg/mL at 2 hours after PQ ingestion. ROM levels before GSH administration were 555 CARR at baseline and 486 CARR at 1 hour later. At 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 hours after the initiation of intravenous GSH administration, the patient showed fluctuating plasma ROM levels of 399, 369, 397, 433, and 388 CARR, respectively.

In summary, 50 mg/kg GSH significantly suppressed ROM levels (mean pre-GSH ROM level, 540.4 ± 115.6; mean post-GSH ROM level, 392.4 ± 137.4; p = 0.04, Wilcoxon signed rank test), but this treatment elicited no effect when the PQ concentration was extremely high. ROM levels in the sole survivor of this study decreased monotonically during the first 8 hours of observation, and finally settled below the mean ROM level observed in the general population. However, in all of the patients who died, the lowest observed ROM level still exceeded that of the general population.

DISCUSSION

Sulfur-containing compounds have been examined as antioxidants in PQ-induced lung injury, because of their inherent antioxidant properties and the early observation that the depletion of reduced GSH enhanced PQ toxicity [8]. Although some studies have shown that alveolar type II cells can supplement the endogenous synthesis of GSH by the uptake of exogenous GSH [9,10], the antioxidative effect of exogenously administered GSH is attenuated by its instability when crossing cell membranes and its rapid hydrolysis while in circulation [11-13].

In the circulatory system, GSH is degraded rapidly by gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase, an enzyme found on the extracellular surfaces of cells, yielding glutamate, Cys, and glycine [14]. In some cells, the degradation of GSH at the cell surface directly provides the cells with the Cys required for GSH synthesis [15]. Although Cys is a critical amino acid for the synthesis of GSH, it is quite reactive in the circulation, resulting in large amounts of Cys being immediately oxidized to Cys2.

In our preliminary study [6,7], the effective doses of Cys, Cys2, and Met against PQ-induced ROS generation in fibroblast cells were assessed using laser scanning confocal microscopy. Both Cys and Met suppressed ROS in a dose-dependent manner at concentrations of 1 to 1,000 µM [6]; the concentrations required to suppress ROS by 50% were 20 µM for Cys and 50 µM for Met. Using metabolite kinetics, with the assumption that Cys and Met are the metabolites of GSH, we estimated that a GSH dose of 50 mg/kg body weight (administered at 205-minutes intervals) is sufficient to produce a serum Cys concentration of 20 µM; likewise, this dose of GSH is sufficient to produce a serum Met concentration of 50 µM when administered at intervals of 427 minutes [7]. Accordingly, a treatment dose of 50 mg/kg GSH was used in this pilot study to examine the effectiveness of intravenous antioxidant therapy against acute PQ toxicity.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of the sequential changes in ROM levels in patients with acute PQ intoxication, during which large quantities of ROS are thought to be generated. ROM levels decreased rapidly after the intravenous administration of GHS (50 mg/kg) in all subjects. However, in three (cases 1, 2, and 5) of the four patients who did not survive (cases 1, 2, 4, and 5), the final observed ROM levels remained higher than the mean value in the general population. This suggests that a dose of 50 mg/kg GSH is insufficient to counter the high levels of ROS generated as a result of PQ intoxication. Furthermore, case 4 died of cardiac arrest 3 hours after PQ ingestion, even after ROM levels had decreased to within the normal range, suggesting that plasma ROM level is not an absolute clinical marker for survival after PQ intoxication.

A limitation of this study is that the sample group was too small for valid statistical analyses. Although acute PQ intoxication provides an invaluable opportunity to observe the clinical characteristics of acute ROS-mediated disease, we encountered difficulties enrolling patients in the study. Most patients with acute PQ intoxication are in a critical state when they arrive at the ER, and typically demonstrate rapid progression/deterioration and a subsequently high mortality rate. In the interest of providing the patient with prompt, high-quality emergency care, there is rarely time to discuss the study objectives with the patient's family and obtain permission to enroll him or her in a clinical study. As such, we were only able to enroll five patients for the present study.

There is also doubt as to the adequacy of the 50 mg/kg dose of GSH used here. This dose was calculated from data obtained using fibroblast cells [6], corresponding to the concentration required to suppress PQ-induced ROS generation by 50%. This raises the question as to whether in vitro results can be applied directly to in vivo situations without any modification. The intensity of ROS formation and the suppression of ROS by the antioxidant may differ under the two conditions, but there is no available way of addressing both aspects.

It is also unclear whether plasma ROM levels area actually reliable markers of ROS formation in cells. We recently reported that neither cross-sectional nor sequential measurements of plasma MDA provided reliable data on ROS formation in patients with acute PQ intoxication (based on repeated measurements of MDA) [16]. The present study confirmed that ROM measurements were reproducible: they remained stable in a patient with diazepam intoxication (7 measurements made over a 4-hour period; Fig. 1). This suggests that the intermediate products of lipid peroxidation may be more reliable than the end-products; that is, ROMs may be a more reliable marker of ROS formation than markers such as MDA that are currently used.

In conclusion, ROM levels were higher in patients with acute PQ intoxication. However, there was no apparent association between plasma PQ and plasma ROM. Plasma ROM levels decreased immediately after initiating the intravenous administration of 50 mg/kg GSH in all patients with PQ intoxication, but not sufficiently so when the PQ concentration was particularly high (i.e., case 5, 22.9 µg/mL at 2 hours after PQ ingestion; case 1, 92.1 µg/mL after PQ ingestion; case 2, 77.7 µg/mL at 3 hours after PQ ingestion). Levels of ROMs in the sole survivor (case 3) decreased monotonically during the first 8 hours of close observation, and thereafter remained at levels similar to those in the general population.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.