Klebsiella pneumoniae Orbital Cellulitis with Extensive Vascular Occlusions in a Patient with Type 2 Diabetes

Article information

Abstract

A 39-year-old woman visited the emergency room complaining of right eye pain and swelling over the preceding three days. The ophthalmologist's examination revealed orbital cellulitis and diabetic retinopathy in the right eye, although the patient had no prior diagnosis of diabetes. It was therefore suspected that she had diabetes and orbital cellulitis, and she was started on multiple antibiotic therapies initially. She then underwent computed tomography scans of the orbit and neck and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. These studies showed an aggravated orbital cellulitis with abscess formation, associated with venous thrombophlebitis, thrombosis of the internal carotid artery, and mucosal thickening of maxillary sinus with multiple paranasal abscesses. Three days later, initial blood culture grew Klebsiella pneumoniae. She recovered after incision and drainage and antibiotic therapy for 37 days.

INTRODUCTION

Orbital cellulitis and orbital abscess in adults are medical emergencies. Delayed or inadequate therapy may result in irreversible loss of vision. Therefore, rapid, correct diagnosis is important. Orbital cellulitis and orbital abscess are usually caused by sinusitis, but cases have been rarely reported following penetrating trauma, orbital surgery, peribulbar anesthesia for eye surgery, endophthalmitis, dental abscess, dacryocystitis, or dacryoadenitis [1-3].

The bacterial organism underlying sinus-related orbital cellulitis is usually unknown, because blood cultures are often negative. Sinus cultures in these cases reveal typical acute sinusitis pathogens, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. Some studies have shown orbital cellulitis and periosteal abscess in adults to be polymicrobial disorders, with a mixture of aerobes and anaerobes [4]. Klebsiella pneumoniae has rarely been identified as a cause of orbital cellulites [5]. However, K. pneumoniae is a common cause of endophthalmitis in patients with a liver abscess [6-8].

Because venous drainage of the middle third of the face and paranasal sinus primarily occurs through the valveless orbital veins, which drain inferiorly to the pterygoid plexus and posteriorly to the cavernous sinus [9], cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis may occur as a complication of a sinus or orbital infection [1]. Therefore, cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis itself may lead to blindness and is a serious medical emergency.

Here we present a case report of K. pneumoniae orbital cellulitis with abscess formation associated with cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis that spread from a parapharyngeal abscess and was treated successfully with antibiotics and surgery.

CASE REPORT

A 39-year-old woman visited the emergency room complaining of right eye pain and swelling over the preceding three days. Her past medical history was unremarkable, and she was not taking any medications. There was no history of alcohol or tobacco use, or abuse of intravenous drugs. The patient also presented with fever, right otalgia, and right amblyopia.

On admission, the patient had a fever of 38℃ All other vital signs were stable (pulse 80 beats per minute, blood pressure 120/80 mmHg, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute). Physical examination revealed right periorbital swelling and redness with eye discharge. On ophthalmologic examination, both corneas were clear, but right-sided scleral chemosis and decreased right-sided visual acuity were noted. Although the patient had never been diagnosed with diabetes, her eye examination showed severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Blood count showed hemoglobin of 12.8 g/dL, white cell count of 7.8 × 103/µL, and platelet count of 196 × 103/µL. Biochemical profile showed hyperglycemia (random glucose level 277 mg/dL) and HbA1c of 9.8%. The fasting plasma and postprandial 2-hour C-peptide levels were 0.89 ng/mL and 1.14 ng/mL, respectively. To determine the type of diabetes, we studied autoantibodies; the results showed that the anti-GAD antibody was below 0.20 U/mL, anti-insulin antibody was 3 U/mL, and islet cell antibody was negative. We evaluated the patient further for diabetic microvascular complications. The patient had severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy and peripheral neuropathy, along with nephropathy in the microalbuminuria range (130.9 mg/24 hr). Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

The work-up of the orbital infection included a computed tomography (CT) scan: the initial orbital CT showed non-specific swelling of the right conjunctival soft tissue, which represented inflammation of the orbit. Therefore, we diagnosed the patient with orbital cellulitis and new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The patient was treated empirically with intravenous ceftriaxone 1 g q.d., ampicillin-sulbactam 750 mg q.i.d., and amphotericin 75 mg q.d. for endophthalmitis and insulin lispro 8 units and insulin glargine 20 units with subcutaneous injection for the diabetes mellitus. Three days later, the results of the initial blood culture reports showed growth of K. pneumoniae. We added oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg b.i.d., and discontinued ampicillin-sulbactam based on the sensitivity results.

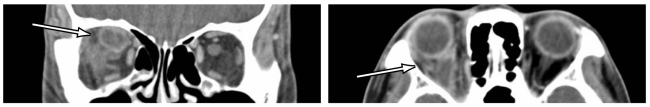

On the third hospital day, the patient complained of anterior neck swelling and aggravated right amblyopia. We followed up with CT scans of the orbit and neck and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. The results showed an aggravated orbital cellulitis with abscess formation, associated with right cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis, thrombosis of the right petrous and proximal internal carotid artery, mucosal thickening of the right maxillary sinus and ethmoid sinus, and right nasopharyngeal, parapharyngeal, and retropharyngeal abscesses (Figs. 1 and 2).

Localized abscess in superior portion of right orbital cavity of 39-yr-old female patient. The arrows show abscess cavities with peripheral enhancement.

Internal carotid artery flow occlusion from carotid bifurcation (A and B) due to parapharyngeal abscess propagation (C). (D) The upper white arrow shows the right cavernous sinus bulging due to inflammation, and the lower white arrow shows invisible internal carotid artery occlusion. The gray arrow shows an intact left internal carotid artery.

The orbital abscess was drained twice in the operating room on the sixteenth and thirty-fifth hospital days by an ophthalmologist. At the second incision and drainage, the otorhinolaryngology department was consulted due to right nasopharyngeal, parapharyngeal, and retropharyngeal abscesses; they were also treated by incision and drainage.

In relation to multiple intracerebral vessel occlusions, the neurology department was also consulted, and the patient was started on antiplatelet medication following the incision and drainage. Follow-up brain magnetic resonance angiography was performed, which revealed right superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis, right cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis, and right skull base osteomyelitis, related to the right nasopharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscess propagation and internal carotid artery flow occlusion at the carotid bifurcation. However, the right middle cerebral artery and anterior cerebral artery flow, supplied through the collateral anterior and posterior communicating arteries, was maintained.

After 37 days in the hospital, the patient recovered from the orbital, nasopharyngeal, and parapharyngeal abscesses after treatment with antibiotics and incision and drainage. Diabetes mellitus was treated by subcutaneous insulin glargine self-injection through the outpatient department. Since discharge, the patient has changed from insulin glargine to an oral hypoglycemic agent. She is followed by the endocrinology and ophthalmology outpatient department. Her right visual acuity is mildly decreased, but has recovered well overall.

DISCUSSION

In this patient presenting with complaints of right eye pain and swelling, there was no evidence of diabetes at the initial emergency room visit. The ophthalmologist's examination revealed diabetic retinopathy in the patient's right eye, although she had no prior diagnosis of diabetes. Therefore, orbital cellulitis was suspected, and the patient was started with multiple antibiotics initially. CT was followed up due to additional complaints of neck swelling and pain, and multiple abscesses were noted in the nasopharynx, parapharynx, and retropharynx. There have been many reports describing orbital abscess originating from sinusitis in children and adults. However, this patient had not only sinusitis, but nasopharyngeal, parapharyngeal, and retropharyngeal abscesses, as well. K. pneumoniae bacteremia was also demonstrated. We suspect that the K. pneumoniae from the nasopharyngeal, parapharyngeal, and retropharyngeal abscesses metastasized to the orbit by hematogenous spread.

Usually, in cases with bacteremia, endogenous endophthalmitis is caused by hematogenous spread. The patient presented here had no evidence of endophthalmitis. The clinical diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis was based on the patient's history and eye examination: such a diagnosis is confirmed by culture of the vitreous or the aqueous body [1, 6-9]. K. pneumoniae is not found in the vitreous or aqueous body, but by blood culture. The eye discharge and vitreous culture revealed no bacterial growth. Pathology in these cases may not reveal a pathologic organism, but only necrotic material.

Usually, endogenous endophthalmitis or metastatic infection spreads from a previously existing infectious condition (i.e., liver abscess) in diabetic patients [10]. The patient in this case had no previous infectious history. However, she had unrecognized diabetes. For evaluation of the focus of infection we performed an abdominal sonogram, but this examination revealed normal liver parenchyma and no other infectious foci.

In this case, the patient appeared to have nasopharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscesses and an eye infection, as well as diabetes mellitus at initial presentation. All diabetic patients with orbital cellulitis should have fungal infection excluded, because rhinocerebral mucormycosis frequently manifests as orbital cellulitis; diabetic patients are susceptible to fungi and other unusual pathogens [1]. We did not think that mucormycosis was present in this case, because fungal stain and culture of the vitreous, eye discharge, and blood were all negative. Post-operative pathology revealed no fungal hyphae in the abscess.

K. pneumoniae is a virulent organism in diabetes mellitus, because neutrophil function is decreased and neutrophil phagocytic activity is impaired in diabetic patients. Nevertheless, there is only one published report of K. pneumoniae orbital cellulitis presenting in diabetic patients [5].

In this case, intravenous antibiotics and surgical drainage procedures were utilized without complication. Surgery can remove most of the inflammatory cells and pathogens, while antibiotics eradicate the latter only. Thus, a combination of surgery and intravenous antibiotics (or intravitreous antibiotics) may achieve better visual outcomes in adult orbital cellulitis, especially when accompanied by orbital abscess formation.

In Asian countries, there are many reports of endogenous endophthalmitis from K. pneumoniae. However, to our knowledge, this is the first reported case of K. pneumoniae orbital cellulitis with abscess formation associated with invasive vascular occlusion that spread from a deep neck infection.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.