Endoscopic Pancreatic Sphincterotomy: Indications and Complications

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Although a few recent studies have reported the effectiveness of endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy (EPST), none has compared physicians' skills and complications resulting from the procedure. Thus, we examined the indications, complications, and safety of EPST performed by a single physician at a single center.

Methods

Among 2,313 patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography between January 1996 and March 2008, 46 patients who underwent EPST were included in this retrospective study. We examined the indications, complications, safety, and effectiveness of EPST, as well as the need for a pancreatic drainage procedure and the concomitant application of EPST and endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST).

Results

Diagnostic indications for EPST were chronic pancreatitis (26 cases), pancreatic divisum (4 cases), and pancreatic cancer (8 cases). Therapeutic indications for EPST were removal of a pancreaticolith (10 cases), stent insertion for pancreatic duct stenosis (9 cases), nasopancreatic drainage (7 cases), and treatment of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (1 case). The success rate of EPST was 95.7% (44/46). Acute complications of EPST included five cases (10.9%) of pancreatitis and one of cholangitis (2.2%). EPST with EST did not reduce biliary complications. Endoscopic pancreatic drainage procedures following EPST did not reduce pancreatic complications.

Conclusions

EPST showed a low incidence of complications and a high rate of treatment success; thus, EPST is a relatively safe procedure that can be used to treat pancreatic diseases. Pancreatic drainage procedures and additional EST following EPST did not reduce the incidence of procedure-related complications.

INTRODUCTION

Anatomically, the sphincter of Oddi is divided primarily into the bile duct sphincter located in the distal common bile duct, the pancreatic duct sphincter forming the distal pancreatic duct, and the ampullary sphincter, which is present in the common bile duct and the common pancreatic duct. In endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), only the ampullary sphincter and bile duct sphincter are resected, while the pancreatic sphincter is left intact [1]. In the clinical setting, EST was first used in 1974 by Kawai in Japan and Classen in Germany. Since then, its safety and effectiveness have been demonstrated and it is acknowledged as an important procedure in the diagnosis and treatment of biliary disease [2].

Endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy (EPST) was first described by Fuji et al. in 1976. Because of its technical difficulty and complications, however, its use has been restricted in the clinical field [3]. Because of this, the methods, indications, and safety of EPST have not been established. Various proposals have been made as to whether EST or EPST should be performed first [4-8]. Elton et al. reported that the use of a pancreatic stent and endoscopic nasopancreatic drainage (ENPD) following EPST could reduce the incidence of complications [9]. According to other studies, however, the usefulness of ENPD is questionable [10]. Very few recent studies [10] have reported on the safety and complications of EPST performed by a single physician at a single center.

We examined the indications, complications, and safety of EPST, and compared the incidence of complications in cases when a pancreatic drainage procedure was performed. In particular, we compared procedures in which EST following EPST was performed and those in which EPST was performed alone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

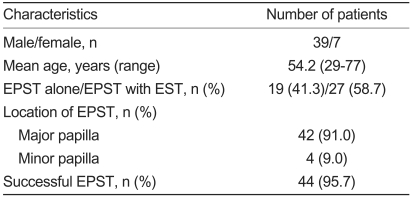

Of 2,313 patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) at Hanyang University Medical Center between January 1996 and March 2008, 46 patients who underwent EPST were enrolled. These patients consisted of 39 men and 7 women (mean age 54.6 and 52.4 years, respectively; Table 1).

Methods

EPST was performed for either the main pancreatic duct or the accessory pancreatic duct, or for the main pancreatic duct together with the accessory pancreatic duct. For endoscopy, a duodenoscopy was performed. Based on the location and type of orifice, the incision was made using a cutting and coagulation blended current, with a standard pull-type papillotome or needle knife. During the EPST procedure, midazolam, pethidine, and Buscopan were intravenously infused as needed. For main pancreatic sphincterotomy, a 5-10 mm incision was made in a 12-2 o'clock direction, along the axis of the main pancreatic duct from the opening of the pancreatic duct. An incision was made up to the upper margin of the hooding fold [11]. For accessory pancreatic duct incisions, the location of the accessory pancreatic duct was confirmed using a specialized catheter. The incision was attempted by inserting a papillotome using a 0.018-inch guidewire. Otherwise, the incision was made using a needle knife papillotome [11]. In patients with severe pancreatic stenosis, a pancreatic stent and ENPD were inserted, if necessary. All patients were given a full explanation about the procedure and provided written informed consent.

Treatment success in EPST was defined as cases in which the opening of the pancreas could be successfully approached following the procedure. Pancreatitis was defined as cases in which serum amylase exceeded three times the normal value in the presence of epigastric pain, even 24 hours after the procedure. Bleeding was defined as cases in which a blood transfusion was carried out after hemoglobin decreased by more than 2 g/dL within a day after the procedure. The definitions and severity of other complications were based on the classification system of Cotton et al. [12]

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for windows, version 12.0 (SPSS inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A cross-tabulation was carried out using the chi-square test and the Mann-Whitney U-test. P values <0.05 were deemed to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

In the 46 patients, the success rate of EPST was 95.7% (44/46). Two cases of failure occurred, both in accessory pancreatic duct dissections. A main pancreatic sphincterotomy was performed in 42 cases (91.3%), while an accessory pancreatic sphincterotomy was carried out in four cases (8.7%, Table 1). The causative factors for chronic pancreatitis requiring EPST involved alcoholism (63%) and unknown causes (21%). Anatomical anomalies, such as anomalous union of the pancreaticobiliary duct (AUPBD) and pancreatic divisum, accounted for the other 16% (data not shown).

Indications for EPST

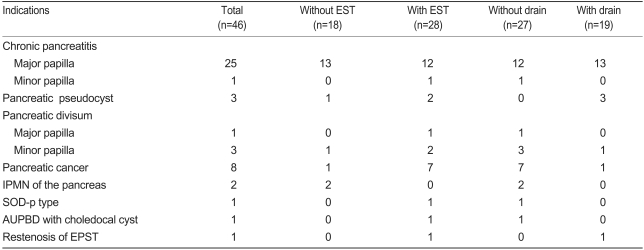

The most frequent diagnostic indication (26 cases) was chronic pancreatitis, with or without concurrent pancreaticolith and dilatation of the pancreatic duct. Eight cases occurred in which the procedure was performed to biopsy the pancreatic duct and to inspect it on suspicion of pancreatic cancer. In two cases, the procedure was performed to assess intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) within the pancreatic duct. In four cases, the procedure was carried out to diagnose and treat pancreatic divisum. In three cases, the procedure was conducted to diagnose and treat a pancreatic pseudocyst. In one case, the procedure was performed because of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD). In one case, the procedure was performed because of the AUPBD and a choledochal cyst, and in one case because of restenosis of the pancreatic duct. The number of patients who underwent EPST alone was 18 (38.1%), while the number of patients who underwent EPST concomitantly with EST was 28 (60.9%). The number of patients who underwent pancreatic drainage procedure following EPST was 19 (41.3%), and the number of patients who did not undergo any pancreatic drainage procedure was 27 (58.7%, Table 2).

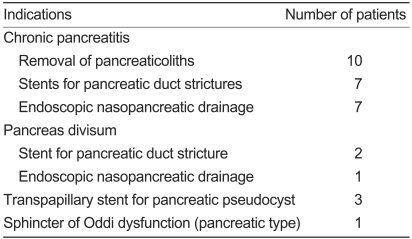

In terms of therapeutic indication, EPST was performed for pancreaticolith removal in ten cases, the insertion of a stent in a stenotic lesion in nine cases, endoscopic nasopancreatic duct drainage in seven cases, the insertion of a pancreatic stent for the treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts in three cases, and the treatment of SOD in one case (Table 3).

Complications of EPST

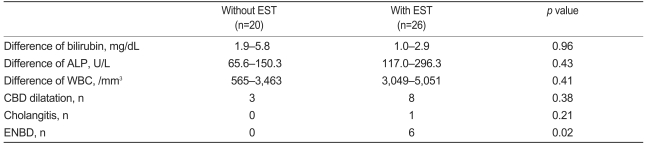

Acute complications, which occurred following EPST, included five cases (10.9%) of pancreatitis and one of cholangitis (2.2%). Severe complications found in the literature, such as bleeding, perforation, pancreatic duct rupture, and sepsis, for which the hospitalization period was prolonged, did not occur. Eight cases of hyperamylasemia were observed that were not clinically notable, and one case of bleeding in which hemostasis was attempted by injecting epinephrine at the site where EPST was performed. Complications developed in two cases (7.1%, 2/28) in which EPST with EST and four cases (22.2%, 4/18) in which EPST alone was performed; however, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.19). Laboratory findings were compared before and after the procedure between the groups in which EPST with EST and EPST alone were performed. Mean total bilirubin was higher in the group in which EPST with EST was performed versus the group in which EPST alone was performed (3.1 mg/dL vs. 0.8 mg/dL, respectively; p=0.36). Mean alkaline phosphatase was also higher in the group in which EPST with EST was performed versus the group in which EPST alone was performed (337.6 U/L vs. 101.5 U/L, respectively; p=0.35). In other laboratory findings, differences were not statistically significant (Table 4).

The incidence of complications was 17.6% (3/17) in cases in which pancreatic drainage was performed and 10.3% (3/29) in other cases. This difference was not statistically significant (p=0.66; data not shown). In cases in which complications occurred, the symptoms were improved only by medical treatments. In no case was the hospitalization prolonged, and no death occurred. Of the 46 subjects, follow-up observations were available for 34 patients. In these patients, the mean follow-up period was 62.6 months (range, 1-132 months). The only late-stage complication associated with EPST was one case of restenosis of the pancreatic duct, which developed after 38 months (2.1%, 1/46).

DISCUSSION

EST has been used for treatment since the 1970s, and is acknowledged as a relatively safe procedure based on studies reporting that the early complication rate was about 10% and the mortality rate was about 1%. In contrast, EPST was introduced to the clinical setting about 10 years later in the 1980s [10]. In recent years, the clinical indications of EPST have become more widely accepted, but due to the low frequency of the procedure and procedure-related complications, no standard treatment regimen has been established. Elton et al. proposed that EPST be used for the diagnosis and treatment of various pancreatic diseases, such as SOD, chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocysts, pancreatic divisum, papillary adenoma, pancreatic cancer, and pancreatic fistula [9]. EPST makes it easier to approach the pancreatic duct to insert a pancreatic stent, remove a pancreatolith, and biopsy tissue from a pancreatic stenosis. It is also used in the treatment of pancreatic sphincter dysfunction. As described here, EPST is a useful procedure, together with pancreatic drainage, for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic diseases. However, because of operator concern regarding technical difficulties and the occurrence of complications, EPST is not performed as frequently as EST [13].

The incidence of complications following EPST is similar to that following EST. Early-stage complications include pancreatitis, bleeding, duodenal perforation, and cholangitis [10-15]. The incidence of complications following EPST has been reported to be 3.2% to 15.7% (mean, 13.6%). In the current study, we made a comparison of other reports on the incidence of severe complications for which hospitalization was prolonged or treatment was needed, excluding mild complications requiring no treatment [11,13,15]. This analysis showed no difference in the incidence of complications or their severity following EPST. Most of the complications were dealt with by conservative management only. In no case was the treatment period prolonged or any additional procedure or surgery needed due to the occurrence of a procedurerelated complication, such as severe bleeding, pancreatitis, or perforation. Thus, we conclude that EPST is a relatively safe procedure, and the incidence of complications due to its technical difficulty was actually lower than for EST.

EPST is a single procedure, but it is rarely used alone in diagnosis or treatment. In many cases, it is used concomitantly with other procedures, such as the removal of pancreaticoliths, the insertion of pancreatic stents, and the dilatation of pancreatic stenosis. Therefore, symptoms deemed to be complications of EPST cannot be stated to have originated solely or directly from EPST. Jacobs et al. [10] conducted a long-term follow-up study at a single institution (n=171, 18-124 months) and reported that the reprocedure rate due to findings such as restenosis was 9.9% (17/167) after a mean period of 7 months (range 0.5-36 months). In the current study, however, late complications were noted in 2.1% (1/46) of the cases, a considerably smaller number. These results may have originated from selection bias due to the small number of enrolled patients and because many were lost to follow-up (12/46, 26%). Slight differences in the incidence of complications seen in other studies may also have been due to the heterogeneous characteristics of the subjects.

In the current study, a single investigator performed the procedure at a single institution and conducted the follow-up study. The results showed that EPST did not cause late complications requiring treatment. The success rate for EPST was 95.7% (44/46), similar to that reported in other studies; thus, EPST was considered to be a relatively safe procedure. This might not have been attributable to EPST being a technically simple procedure, but occurred because many experts who have experience in EST preferentially attempt to use EPST. In other words, when physicians carry out endoscopic therapy at the pancreatic duct, they are already experienced and can thus be expected to have lower complication rates.

Various proposals have been made regarding whether EST or EPST should be preformed first. A theoretical basis for the concomitant use of EST with EPST is that the swelling of the opening of ampulla can cause bile duct stenosis and cholangitis due to thermal injury resulting from the EPST procedure [4,5]. Therefore, the cutting wave, rather than the coagulation wave, is recommended to be used more frequently [6]. In the group in which EPST followed EST versus the group in which EST was preceded by EPST, this is advantageous in that a papillotome could be readily inserted and the scope of the EPST incision could be accurately measured because the opening of the pancreatic duct could be clearly disclosed [6,13]. Fuji et al. stated that the reason for the preceding use of EPST is that determining the scope of the incision is difficult due to damage to the hooding fold in cases when EST is performed first [7]. Recent randomized controlled trials have shown that EST is not an essential procedure, but that the procedure should be determined based on the status of bile duct prior to the procedure in cases in which EPST is needed [8]. In the current study, the incidence of complications was similar between the group with EPST alone and the group experiencing EPST with EST. The incidence of complications was not lower in the EPST with EST group compared to the EPST-alone group. As described here, the reason why no significant difference was detected in the incidence of complications may have been due to selection bias occurring in such cases; the comparison was based on the same patient condition not being present between the EPST with EST group and the EPST-alone group and patients who concurrently had biliary disease prior to the procedure being included in the EPST with EST group.

Various opinions exist regarding the incidence of complications following pancreatic drainage and the rationale for it. Elton et al. reported that the insertion of pancreatic duct or nasopancreatic drainage could reduce acute complications [9]. Through an analysis of 572 cases of EPST, Hookey et al. maintained that pancreatic drainage was needed to lower the intrapancreatic pressure generated by papillary edema following EPST [16]. This view has been challenged, however, and many negative opinions exist regarding whether nasopancreatic drainage does indeed reduce complications [10,17]. In contrast, pancreatic drainage has been reported to reduce the occurrence of acute complications in some cases, including SOD [9,15].

However, in the current study, no significant difference was found in the incidence of complications between the group in which pancreatic drainage was performed and the group in which it was not. In contrast, the occurrence of hyperamylasemia increased in the group in which pancreatic drainage was performed. These findings may be the result of stimulation of the pancreatic duct due to the insertion of a pancreatic stent or nasopancreatic drainage in severe pancreatic stenosis or cases in which a small pancreaticolith was present. Indications for EPST in the current study included chronic pancreatic diseases, such as chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, and pancreatic divisum. In fact, the incidence of complications apparently increased following pancreatic drainage. Of the indications in the current study, the usefulness of pancreatic drainage following papillectomy could not be statistically evaluated because of the small number of enrolled patients.

Other limitations of the current study include the following: (1) The current study was designed as a retrospective analysis and this may have caused selection bias, leading to statistical error. (2) The follow-up period was substantial. Due to the small number of enrolled patients, however, the current study could not reflect demographic characteristics such as age and gender. For example, the current study could not consider risk factors in a high-risk group of patients in whom complications such as pancreatitis can occur. (3) Some patients were lost during the follow-up period, which lowered the reliability of the statistical analysis of late complications.

Despite these limitations, because the current study was conducted by a single investigator at a single institution, the consistency of the treatment procedure was high and its correlation with the complications occurring following EPST could be established.

In conclusion, the current study showed that EPST is a relatively safe procedure, with a high success rate, and that it can be used for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic diseases. EPST showed a lower incidence of complications and a higher rate of treatment success; thus, EPST is a relatively safe procedure that can be used to treat pancreatic disease. Additionally, performing EST after EPST is not always necessary. Pancreatic drainage following EPST did not reduce the incidence of procedurerelated complications in this study. Pancreatic stimulation due to the procedure can cause mild complications. Further larger-scale, prospective studies are warranted to determine the risk factors for developing complications.