A Case of Pulmonary Cryptococcosis by Capsule-deficient Cryptococcus neoformans

Article information

Abstract

Pulmonary infection by capsule-deficient Cryptococcus neoformans (CDCN) is a very rare form of pneumonia and it is seldom seen in the immunocompetent host. The authors experienced a case of pulmonary cryptococcosis by CDCN in 25-year-old woman who was without any significant underlying disease. The diagnosis was made from the percutaneous lung biopsy and special tissue staining, including Fontana-Masson silver (FMS) staining. Fungal culture confirmed the diagnosis afterward. Her clinical and radiologic features improved under treatment with fluconazol. It's known that CDCN is not so readily confirmed because fungal culture does not always result in growth of the organism and the empirical fungal stain is not helpful for the differentiation between CDCN and the other infections that are caused by the nonencapsulated yeast-like organisms. In this report, we emphasize the diagnostic value of performing FMS staining for differentiating a CDCN infection from the other confusing nonencapsulated yeast-like organisms.

INTRODUCTION

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated opportunistic human pathogenic yeast that can cause meningitis and pulmonary or systemic infections. The organism is ubiquitous and there are no localized epidemic areas. Pulmonary cryptococcosis is a potentially fatal pulmonary infection, and it is caused by the inhalation of the aerosolized organism and it has been associated with exposure to pigeon droppings and other bird droppings1). This organism has emerged as a frequent finding inthe patients with cell-mediated immunodeficiency, i.e., patients with lymphoid malignancy, organ transplants, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and those patients receiving steroids or immunosuppressive agents2, 3). In recent years, pulmonary cryptococcosis is being recognized with increased frequency in both immunologically compromised patients and those patients without any obvious predisposing factors. In clinical practice, the diagnosis mainly relies on tissue section and culture. Although the morphologic features of C. neoformans (oval and round budding yeasts that range in size from 5 to 10 µm, and they have a mucicarmine positive capsule) are distinctive and diagnostic, the case of a CDCN infection that is morphologically indistinguishable from the other nonencapsulated yeast-like organisms, especially blastomycosis and histoplasmosis, is rare4-6). This report describes how we employed FMS staining for differentiating CDCN from the other confusing nonencapsulated fungal species.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with nonresolving pneumonia. The patient had felt well until two weeks before her admission, when she began to experience a dry cough, dyspnea and pleuritic pain. Her respiratory symptoms did not respond to a 5-day course of oral cephalosporin, and macrolide antibiotics had been prescribed before her admission. She was a non-smoker with unremarkable past medical history.

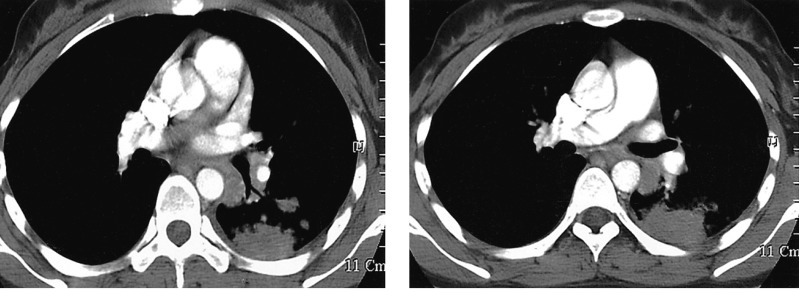

On admission the body temperature was 36.6℃, the heart rate was 84/min, the respiration rate was 20/minute and the blood pressure was 100/80 mmHg. On physical examination, the patient was alert and not in great discomfort. There was a crackle sound over the left lower lung zone. There was no organomegaly or lymphadenopathy. Detailed examination of the cardiovascular system and abdomen was unremarkable. Chest radiography disclosed a pneumonic infiltration on the left lower lung field and there was no cardiomegaly (Figure 1A). Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the chest revealed a consolidation with air-bronchogram in the left lower lobe and a small amount of pleural effusion (Figure 2). The complete blood count showed a normal white cell count (8.4×109/L). There was no hypoxemia on the blood gas analysis (pH 7.4, PaCO2 37.2 mmHg, SaO2 98%) when she was breathing room air. The other laboratory investigations showed normal electrolytes and renal and liver function tests. The fasting glucose was normal. The serum anti-HIV antibody was negative. The serum immunoglobulin levels (including IgG, IgA and IgM) were normal. Pulmonary function testing showed a mild restrictive pattern (the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) was 2.50/2.32L; the ratio was 93%), and there was a normal diffusion coefficient for carbon monoxide (DLco: 109%). The initial examination of the sputum for acid-fast bacilli with gram staining and culture did not reveal any organisms. The blood culture was sterile after 7 days incubation. We then conducted a bronchoscopic examination. There were no endobronchial abnormalities. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) revealed the lymphodominant nature (a lymphocyte count of 70%, the macrophages were 28%). The BAL fluid culture was negative and there were neither acid-fast bacilli nor any pathogens.

(A) Posteroanterior chest radiograph revealing the dense left lower lobe opacity on admission. (B) The follow-up posteroanterior chest radiograph, which was obtained after the completion of a 6-month course of therapy with oral fluconazole, revealed a residual scar in the left lower lobe.

Axial contrast-enhanced chest CT scan revealed the irregular marginated lung consolidation at the left lower lung on admission.

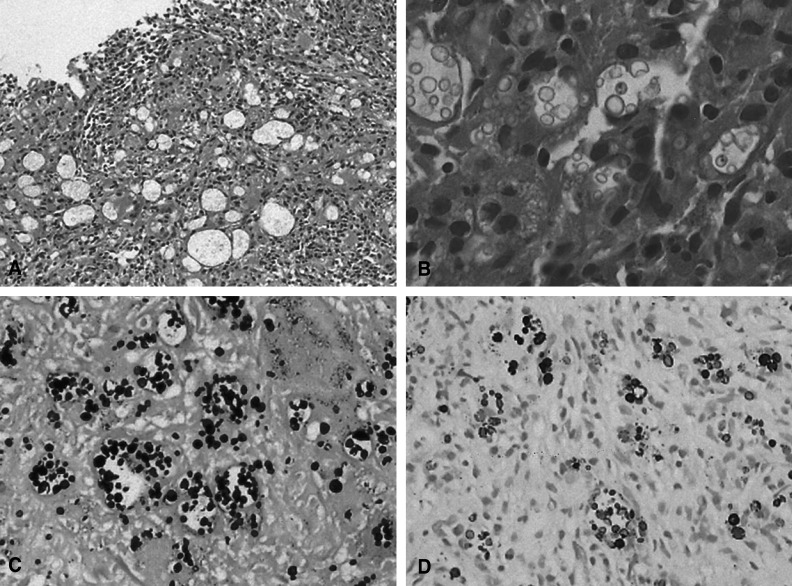

During the first six days of this patient's admission to our hospital, her annoying respiratory symptoms and lung consolidation did not improved for all the combination antibiotic treatment (intravenous cefuroxime and oral clarithromycin). We performed a subsequent computed tomography guided percutaneous needle biopsy on the sixth hospital day. The tissue pathology revealed granulomatous lesion including multinucleated giant cells and fungal spores. The specimens were stained with Hematoxilin-Eosin, mucicarmine, Gomori-Methenamine silver (GMS), and periodic-acid-Schiff (PAS). The Hematoxilin-Eosin and GMS stain showed granulomatous inflammation with numerous yeast-like organisms that were surrounded by clear halos, and these organisms were present within multinucleated giant cells and in the intercellular spaces (Figure 3). Mucicarmine staining for capsular material was negative. With performing additional Fontana-Masson silver staining (FMS), the black color in the walls of the organism was disclosed (Figure 3). This special stain pattern is a characteristic of C. neoformans, and especially for the capsule deficient form. Subsequently, the antibiotic regimen was replaced by 1-week of once-a-day intravenous fluconazole treatment and the patient was discharged on oral fluconazole. Further cultures of the lung specimen yielded moderate growth of Cryptococcus neoformans afterward. During the 6-months follow up period her respiratory symptoms and abnormal radiologic feature were markedly improved (Figure 1B).

(A) Histologic examination of the lung biopsy revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation without necrosis (H&E stain, ×100). (B) High power examination of the lung showing several foreign body type multinucleated giant cells that contain many fungal spores (H&E stain, ×400). (C) GMS stain revealed numerous positively stained fungal spores; some spores exhibit narrow-based budding (×200). (D) Fontana Masson silver staining showing numerous positive organisms in the cytoplasm of the multinucleated giant cells (×200).

DISCUSSION

We report on a case of capsule-deficient pulmonary cryptococcal infection that occurred in an immunocompetent host. She was referred to our hospital with a 2 week history of unremitting cough and pleuritic chest pain. Her diagnosis was established by the presence of specially stained Cryptococcus neoformans organisms in the lung biopsy specimen and by the positive tissue culture. When she was treated with a 6-month course of oral fluconazol, the patient showed a favorable clinical course.

The prevalence of isolated pulmonary cryptococcosis has markedly increased in immunocompromised patients, and especially in those with lymphoid malignancy, AIDS or those who have undergone steroid therapy2, 3). Although Cryptococcus neoformans can cause pulmonary or disseminated disease in immunocompromised patients, this condition is rarely encountered in normal hosts and little is known about the disease, particularly its pulmonary involvement7). Furthermore, pulmonary cryptococcosis that is caused by the CDCN form is extremely rare and only a few cases have been described in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no such reports in Korea.

Pulmonary cryptococcal disease can cause a variety of manifestations. The chest radiography of the immunocompetent host can be variable and it tends to present as a pattern of community acquired pneumonia. The radiologic pattern in the immunocompromised hosts has demonstrated a wide variety of radiographic abnormalities, including solitary or multiple pulmonary nodules that may progress to confluence and cavitation, interstitial infiltrates or widely disseminated parenchymal disease with a miliary pattern. In the immunocompromised hosts, cryptococcal infection can present as adult respiratory distress syndrome8).

C. neoformans causes a variety of tissue responses. The disease can cause the formation of granulomas, fibrosis and in a few cases, caseous necrosis9). In nature, C. neoformans exist as a 3 to 4m tiny molecule with no capsular material or with only small one, and this allows the organism to become airborne. When the inhaled organism reaches the alveoli, this organism propagates by binary fission and reacquires the characteristic large polysaccharide capsule10). This form is readily identified by its characteristic encapsulated, budding yeast form that stains deep red with mucicarmine and there is minimal or no inflammatory tissue reaction. The lack of tissue reaction to the typical encapsulated form of C. neoformans is associated with the existence of the capsule material. The capsule is a very important virulence factor in the pathogenicity of C. neoformans, which can alter leukocyte migration, phagocytosis and killing by the immune effector cells10, 11). The loss of capsule material elicits an intense inflammatory response that includes early suppuration, phagocytosis and granuloma formation4, 12).

The pathologic diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis is mainly made by the identification of C. neoformans organisms from the cultures and the tissue-section analysis. The commercially available fluorescent antibody stain is a useful diagnostic tool, but this test is not so widely used. Although the confirmative diagnosis is ideally accomplished by culture, it often has to be made from a tissue section when any cultures are not available9). However, a correct diagnosis of CDCN infection by using the tissue section alone may be extremely difficult because of the negative results of mucicarmine staining; in addition, the organism is morphologically indistinguishable from Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis and Coccidioides. immitis in tissue5, 6). In the present case, the organisms appeared as small, round to ovoid, yeast-like organisms with using Hematoxilin-Eosin, GMS and PAS stains. The additional mucicarmine stain for capsular material was negative. In our case, the FMS stain was very useful for the differentiation of the pathogenic fungal species, and especially for distinguishing cryptococcal infection from the other fungal infections that can mimic it with their similar size and shape, tissue response and negative mucicarmine staining. The application of FMS stain to the CDCN organism was first reported by Kwon-Chung et al. (1981)13). FMS stain detects melanin and other silver reducing substances, and it is useful for staining the cell wall of C. neoformans irrespective of the presence or absence of capsular material. Using this stain relies on the fact that C. neoformans produces a melanin-like pigment in a substratum that contains dihydroxy or polyhydroxy phenols13).

As previously described, pulmonary cryptococcosis takes a variable clinical course. Asymptomatic pulmonary infection has been noted in the immunocompetent patients who had no extra-pulmonary involvement, and these patients have been reported to recover spontaneously14). The risk factors for serious or fatal complications in immunocompetent hosts have been described mainly for the patients with meningitis and disseminated infection. According to recent therapeutic guidelines, the immunocompetent patient who presents with mild-to-moderate symptoms is an indication for treatment with fluconazole, 200400 mg/d for 612 months. In the asymptomatic immunocompetent patients, antibiotics treatment is optional15). In Korea pulmonary cryptococcosis is commonly misdiagnosed as a pulmonary tuberculosis or lung tumor16). With a recent widespread use of immunosuppressive agent including steroid, the disease prevalence is increasing. A high index of suspicion is required in patients who do not respond to initial empirical antimicrobial treatment, especially young patients or those without comorbidity.

The current case emphasizes that FMS staining and tissue culture can be used for the pulmonary cryptococcosis caused by the CDCN organism. Furthermore, this case shows the possibility of making an error in the diagnosis of the specific fungal infection when the diagnosis is accomplished entirely on the basis of tissue reaction and the morphologic findings of the organism.