Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma-Unspecified (PTCL-U) Presenting with Hypereosinophilic Syndrome and Pleural Effusions

Article information

Abstract

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a clinical disorder characterized by persistent eosinophilia and systemic involvement, in which a specific causative factor for the eosinophilia cannot be verified during a certain period of time. There have been only a few reported cases of this syndrome associated with malignant lymphoma. We report a case of peripheral T-cell lymphoma-unspecified with hypereosinophilic syndrome. The patient was a 42-year-old woman with an uncontrolled fever and a sore throat. Eosinophilia was observed on the peripheral blood smear. We confirmed the diagnosis by bone marrow and liver biopsies:. A bone marrow aspiration demonstrated markedly increased eosinophils (24.8%), and a liver biopsy demonstrated infiltration by scattered eosinophils and atypical lymphoid cells, which were confirmed to be T-cell lymphoma cells. This case was a distinctive presentation of peripheral T-cell lymphoma with hypereosinophilic syndrome, probably due to a paraneoplastic condition.

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilia is commonly observed with atopic disorders, parasitic infection, fungal infection, mycobacterial infection, drug reactions, and collagen-vascular diseases. More recently, attention has been drawn to its association with malignancies1-4). Malignant lymphomas and leukemias associated with eosinophilia, have been reported sporadically6-8). Hypereosinophilic syndrome is a clinical disorder characterized by persistent eosinophilia and systemic signs, in which the specific causative factor for the eosinophilia cannot be confirmed for a certain period of time1-4).

Only a few reported cases of this syndrome have been associated with malignant lymphoma6-8); and only a few reports described the transition of HES to lymphoproliferative disorders, although, the time periods varied in those cases before the diagnosis of a malignancy was made. We report a case of hypereosinophilic syndrome associated with peripheral T-cell lymphoma, which involved the liver and caused pleural effusions.

CASE REPORT

A 43-year-old woman was hospitalized in January 2004, with a 2-month history of a fever, a dry cough and a sore throat, which were refractory to antibiotic therapy. She had received supportive care for eosinophilia in another hospital. A physical examination demonstrated a 1×1 cm non-tender cervical lymph node, hepatosplenomegaly 3 cm below the costal border, peritonsillar exudates and pretibial pitting edema. Diffuse crackles were auscultated in the left lower lung field, and no heart murmur was detected. The peripheral blood counts were: hemoglobin, 11.3 mg/dL; platelets, 182,000/mm3; and white blood cells, 20,730/mm3 (neutrophils 46%, lymphocytes 13%, monocytes 3%, eosinophils 36%, basophils 1%, and plasma cell 10%). The absolute eosinophil count was 7,462/mm3. LDH was 1,529 IU/L, serum IgE 9.5 IU/mL and b2-microglobulin 2.70 mg/L. The sputum culture, blood culture, throat swab culture and pleural fluid culture provided negative results. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, VDRL, and HIV diagnostic tests were negative. The EBV VCR IgG antibody was positive; while the IgA and IgM antibody tests were negative. Multiple examinations of stool specimens for ova and parasites were negative.

Clonorchis sinensis, paragonimus westermani skin test and cysticercus, paragonimus, sparganum, clonorchis, and toxocara specific IgG antibody tests gave negative result.

An electrocardiogram and an echocardiogram were normal. The CD3/CD4 lymphocyte percentage was 66.1%, and the CD3/CD8 lymphocyte percentage was 14.6%. The total CD3/CD4:CD3/CD8 (Helper:Suppressor) ratio was 4.53, which was increased compared to the normal reference range of 0.9-3.6.

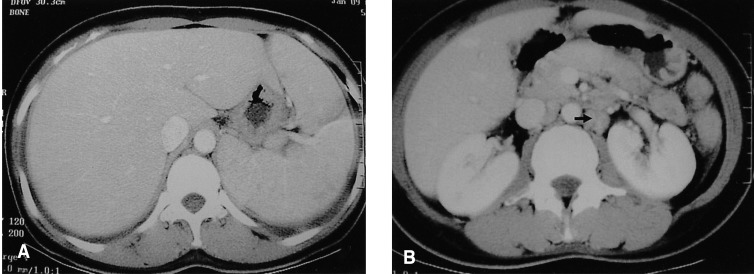

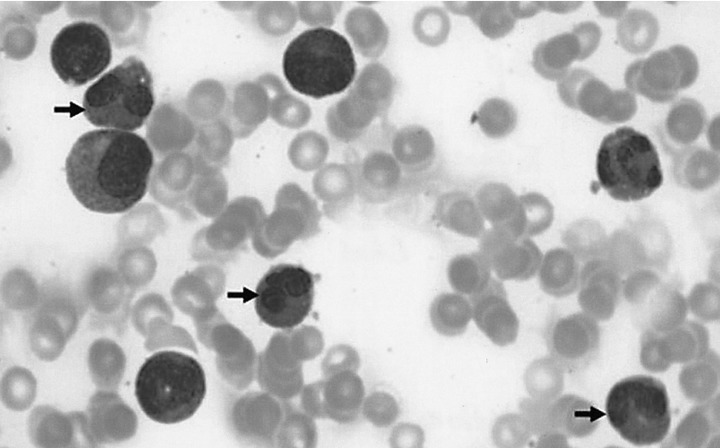

A chest X-ray revealed mild pulmonary congestion and a left pleural effusion (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen demonstrated diffuse hepatosplenomegaly, bilateral pleural effusions, and left paraaortic, subcarinal, and paratracheal lymphadenopathy (Figure 2). Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed a markedly increased number of eosinophils (24.8%), and a significant number of plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figure 3). The patient's cytogenetic analysis demonstrated a normal karyotype, 46 XX. Despite treatment with empirical antibiotics, the fever and the sore throat persisted.

(A) A chest X-ray demonstrated mild pulmonary congestion and a left pleural effusion. (B) A chest CT demonstrated mild pulmonary congestion and bilateral pleural effusions (arrow).

Abdominal CT. (A) Demonstrated diffuse hepatosplenomegaly. (B) Demonstrated left paraaortic lymphadenopathy (arrow).

Bone marrow aspiration demonstrated a markedly increased number of eosinophils (Giemsa stain, ×1000) (arrow).

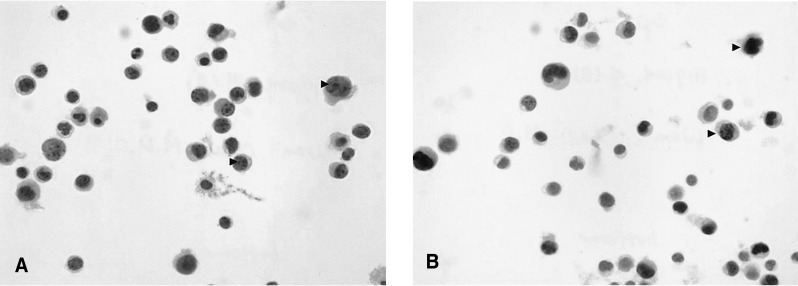

Pleural cytology demonstrated lymphocyte dominant exudates with a few atypical cells. These atypical lymphocytes were suspected to be malignant lymphoma cells, based on the results of immunocytochemistry (CD3, positive; CD20, negative; Ki-67, positive) (Figure 4). A liver biopsy demonstrated a few atypical lymphoid cells and eosinophils in the sinusoids and the portal space, based on the results of immunocytochemistry (CD3, positive; CD20, negative; Ki-67, positive) (Figure 5).

Pleural fluid cytology. (A) Demonstrated a few atypical cells (papanicolaou smear, ×1000) (arrowhead). (B) Demonstrated a few atypical cells (Ki 67 stain, ×1000) (arrowhead).

Liver biopsy. (A) Demonstrated a few atypical lymphoid cells (arrowhead) and eosinophils (H & E stain, ×400) (arrow) in the portal space. (B) Demonstrated eosinophils (Ki 67 stain, ×1000) (arrow) in the portal space. (C) Demonstrated eosinophils (CD3 stain, ×1000) (arrow) in the portal space (CD3 stain, ×1000).

Based on the results of the liver biopsy, the pleural cytology, and the bone marrow biopsy, a diagnosis was made of peripheral T-cell lymphoma with hypereosinophilic syndrome. The patient was treated with two courses of CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2, vincristine 1.4 mg/m2, and prednisolone 100 mg). During chemotherapy, the fever and the eosinophilia improved.

However, the CT of the abdomen, performed on March 25, 2004, demonstrated that the hepatosplenomagaly and the lymphadenopathy, were unchanged. Peripheral blood counts were: hemoglobin, 9.4 mg/dL; platelets, 253,000/mm3; and white blood cells, 7,240/mm3 (neutrophils 41%, lymphocytes 20%, monocytes 10%, eosinophils 29%, basophils 1%, and plasma cell 2%). In addition, a high-grade fever persisted.

The chemotherapy regimen was then changed to IMVP-16 (ifosfamide 1,000 mg/m2, mesna 200 mg/m2, methotrexate 50 mg/m2, and ectoposide 100 mg/m2) plus prednisolone 100mg. After two courses of this chemotherapy, the eosinophilia, the fever and the pleural effusions improved. After the sixth course of chemotherapy, the CT of the abdomen, performed on July 29, 2004, demonstrated that the hepatosplenomagaly and lymphadenopathy had decreased by more than 50 percent (Figure 6). After the eighth course of chemotherapy, 18F-fluorrodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), performed on September 15, 2004, demonstrated no hypermetabolic lesions.

Abdominal CT demonstrated marked improvement in the lymphadenopathy after 6 courses of chemotherapy.

Two months later, follow-up peripheral blood counts were: hemoglobin, 12.4 mg/dL; platelets, 165,000/mm3; and white blood cells, 8,870/mm3 (neutrophils 38%, lymphocytes 8%, monocytes 5%, eosinophils 49%, basophils 0.6%, and plasma cell 1.7%). However, a CT of the abdomen, performed on October 24, 2004, demonstrated that the lymphadenopathy had increased in both size and extent (Figure 7). This was considered a relapse of the disease.

Abdominal CT demonstrated an increase in the size and extent of the lymphadenopathy (arrow), one month after completion of the eighth course of chemotherapy.

Although the patient was subsequently treated with ESHAP chemotherapy (ectoposide 40 mg/m2, methylprednisolone 500 mg, cisplatin 25 mg/m2, and cytarabine 2000 mg/m2), her condition deteriorated. After completion of a course of this chemotherapy, 18F-fluorrodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), performed on November 24, 2004, demonstrated multiple metabolic lesions in the abdominal lymph nodes, the heart, the axillae, the mediastinal lymph nodes, and both lungs. High dose chemotherapy was then recommended, but the patient refused. Supportive care was provided for the continued eosinophilia, the uncontrolled fever, and the sore throat. Two months after the disease become refractory to treatment, the patient died of a cardiac tamponade.

DISCUSSION

The clinical features observed in this case, fulfilled the criteria for a diagnosis of hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES): persistent eosinophilia of 1500 eosinophils/mm3 for at least 6 months, or, the presence of the signs and symptoms of HES disease for 6 months before death; lack of evidence for parasitic, allergic, or other recognized causes of eosinophilia, despite a careful evaluation; and signs and symptoms of organ system involvement or dysfunction, either directly related to the eosinophilia or inexplicable in the given clinical setting1-5).

Reports of hematologic malignancies associated with eosinophilia have included leukemia, lymphoma, malignant histocytosis, and even plasmacytoma. Some authors have described hypereosinophilic syndrome as part of the spectrum of myeloproliferative disorders. However, the mechanism of eosinophilia has largely been described to be due to the production of factors by eosinophils, especially in T-cell malignancies6-8). Only a few reports have described a transition of idiopathic HES to lymphoproliferative disorders and, in those cases, the time periods varied before the diagnosis of a malignancy was made7, 8). The patient in this case, had been ill for 2 months prior to the hospitalization, and the eosinophilia had persisted since the onset of the disease. During those 2 months, she experienced a fever, a dry cough, and a sore throat, which were refractory to antibiotic therapy. Based on the results of the liver biopsy, the pleural cytology, and the bone marrow biopsy, the diagnosis was made of peripheral T-cell lymphoma with hypereosinophilic syndrome. When chemotherapy with IMVP-16 plus prednisolone was administered, both the hepatosplenomegaly and the lymphadenopathy resolved by more than fifty percent.

A possible disease sequence in this patient started with an unrestrained expression of an occult T-cell lymphoma, with a relatively indolent clinical course and secondary hypereosinophilia. There have been several studies of T-cell malignancies associated with eosinophilia, where the majority of the patients were adults. In such cases, the clinical findings were associated mainly with lymphomas and eosinophilia, which implied that the hypereosinophilia was non-idiopathic, rather than a true transition from idiopathic HES to a T-cell malignancy. This differs from the clinical course of the current case.

A second possibility is a de novo development of malignant lymphoma in a host with an immunologic derangement. This patient demonstrated some presumptive signs of immunodeficiency, such as frequent bacterial infections (chronic otitis media and the growth of E. coli from a lymph node aspirate) and a negative cell-mediated immunity skin test during the hospitalization7). Previously, the relationship between hypereosinophilic syndrome and malignant lymphoma had not clearly been defined, and the causative relation remains presumptive at this time. Further investigation is needed to more clearly define the transition from hypereosinophilic syndrome to malignant lymphoma, since it would provide significant assistance in determining the initial treatment and the prognosis. In the present case, we did not determine any specific immunodeficiency that may have caused the lymphoproliferative disease. However, this case had an unusual presentation of a T-cell lymphoma associated with marked eosinophilic tissue infiltration, as well as peripheral eosinophilia. This finding was also related to the therapeutic results and the relapse of the disease.