Visualization of Jejunal Bleeding by Capsule Endoscopy in a Case of Eosinophilic Enteritis

Article information

Abstract

Eosinophilic enteritis is a rare disease characterized by tissue eosinophilia, which can affect different layers of bowel wall. Normally, the disease presents as colicky abdominal pain, and rarely as an acute intestinal obstruction or perforation. In this paper, we report a case of eosinophilic enteritis, hitherto unreported, presenting as an ileal obstruction, and followed by jejunal bleeding, which was visualized by capsule endoscopy. A 62-year-old man received a 15 cm single segmental ileal resection at a point 50 cm from the IC valve due to symptoms of obstruction, which were diagnosed as eosinophilic enteritis. Seventeen days after operation, intermittent abdominal pain occurred again, and subsided upon 30 mg per day treatment with prednisolone. Fourteen days after this pain attack, the patient exhibited hematochezia, in spite of continuous prednisolone treatment. Capsule endoscopy showed fresh blood spurting from the mid-to-distal jejunum, in the absence of any mass or ulcer. This hematochezia rapidly disappeared following a high-dose steroid injection, suggesting it was a manifestation of jejunal eosinophilic enteritis.

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic enteritis is an uncommon disease of unknown etiology, which can affect any area of the gastrointestinal tract, from the esophagus to the rectum, although the stomach and small bowel are most commonly involved1). It usually presents as colicky abdominal pain, and rarely as an acute intestinal obstruction2, 3) or perforation4-6), making the initial diagnosis very difficult. Eosinophilic enteritis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms, since most patients with eosinophilic enteritis can be treated successfully with corticosteroid therapy, if the correct diagnosis is made7). Development of a new capsule video endoscope, which is small enough to be swallowed and has no external wires, fiber-optic bundles, or cables, has made it possible to acquire images of the whole of the small bowel. It has been proven to be very useful in the diagnosis of small bowel disease in the case of negative gastroscopy and colonoscopy8), suggesting it can contribute to the localization of lesions for laparoscopic biopsy, and thus lead to conclusive diagnoses of eosinophilic enteritis. We present the case of a patient who underwent an emergency laparotomy for acute intestinal obstruction due to ileal eosinophilic enteritis, followed by hematochezia due to mid-to-distal jejunal bleeding, which was visualized by capsule endoscopy. The hematochezia was rapidly controlled by high-dosage steroid injection therapy, which suggests that it was a manifestation of eosinophilic enteritis.

CASE REPORT

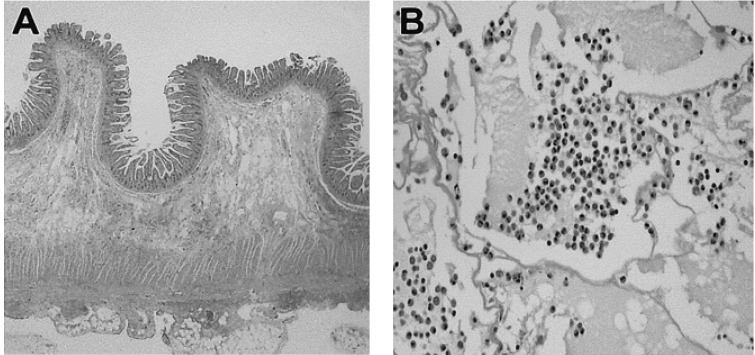

A 62-year-old man visited the emergency room complaining of epigastric and periumbilical pain, which had developed 3 hours prior to his admission. The nature of his complaint was colicky pain, but he had experienced neither nausea nor vomiting. He had no history of abdominal surgery, allergic disease, or food sensitivity. Physical examination revealed right lower quadrant abdominal tenderness, but no rebound tenderness. The patient's leukocyte count was 10,420/mm3 (2.9% eosinophils, normal range [NR], 0~5%). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) examination showed segmental wall thickening of the small bowel and proximal dilatation, mesenteric edema, and focal fluid collection in the adjacent peritoneal cavity (Figure 1). However, there was no abrupt transition in the luminal diameter at either end of the pathologic bowel loop, suggesting a radiological abnormality, other than the strangulation normally observed in a case of intestinal obstruction. The radiological differential diagnosis included segmental enteritis of unclear cause, and focal mesenteric ischemia by a certain kind of systemic vasculitis, or post- strangulation state following the relief of obstruction. Twelve hours after his admission to the emergency room, the abdominal pain progressed, rebound tenderness developed, and finally, an exploratory laparotomy was performed. Exploration revealed edema, congestion, and bluish discoloration of the distal ileum, 50 cm from the ileocecal valve. Only a 15 cm segment was involved, and the remaining bowel was seen to be normal. The proximal bowel was dilated and the distal bowel had collapsed. The involved ileal segment was resected, and end-to-end anastomosis was performed. Gross examination showed an ill-defined mass-like wall thickening with multifocal erosion of the overlying mucosa, 7 centimeters in length, and the surrounding small intestinal mucosa was moderately edematous. Histologically, extensive eosinophilic infiltration was found in the mass-like lesion, which was found from submucosa to subserosa (Figure 2). In the surrounding mucosa, edema with increased eosinophils was also observed. There was found to be no evidence of parasites, granulomas, malignancy, vasculitis, or embolism in the surgical specimen, either in the bowel wall or in the mesenteric vessels. The final diagnosis was eosinophilic enteritis. Two days after the operation, the patient's leukocyte count decreased to 8,070/mm3 (8.7% eosinophils). The pain disappeared and he was discharged normally. At the outpatient clinic, 12 days after the operation, the patient's total IgE was 1,310 u/mL above the normal range (0~100 u/mL), but skin prick test was normal, suggesting no specific allergic etiology. Seventeen days after the operation, similar characteristic abdominal pain developed again in the patient's periumbilical area, but to a milder degree than before the operation. The patient was advised to undergo gastroenterological testing in order to evaluate the abdominal pain, but he refused. Instead he (60 kg-weight) received 40 mg intramuscular injections of methylprednisolone acetate for two days, and simultaneously took 10 mg prednisolone three times per day, resulting in improvement of abdominal pain. Two weeks after this abdominal pain attack, hematochezia occurred for 4 days, in spite of continuous 30 mg prednisolone per day. The patient experienced dizziness, and his hemoglobin decreased from 13.6 g/dL (NR, 13-17 g/dL) to 9.5 g/dL. He was readmitted for a diagnostic work-up. Emergency colonoscopy showed no evidence of bleeding after bowel preparation with colyte, nor did it reveal any definite mucosal abnormality up to the ileocecal valve. Although there was no definite intrinsic mucosal lesion, six pieces of blind biopsy were taken from the hepatic flexure and 40 cm above the anal verge, but the pathologic results indicated only nonspecific change. In addition, gastroduodenoscopy up to the 3rd portion of duodenum revealed no abnormalities, and there was no evidence of bleeding. On the next day, the initial negative 99mTc-tagged red blood cell scan showed a small amount of bleeding from the right iliac artery 2 hours and 30 minutes after injection of 99mTc-tagged red blood cells, and migration of blood into the right ileal lumen after 4 hours and 30 minutes. However, CT angiography and arteriography, which were taken successively, showed no focus of bleeding, indicating that the bleeding had already stopped, or that the bleeding speed was slower than 0.5 mL/min. On the next day, M2A™ capsule endoscopy was performed. It showed that multiple hemorrhagic spots were scattered throughout the proximal jejunum (Figure 3A). After the normal jejunal segment, abrupt spurting of fresh arterial bleeding was detected in the mid-to-distal jejunum, but no ulcer, mass or vascular abnormalities were detected (Figure 3B). The ileum was normal, and the anastomotic site at the ileum was not noticed, suggesting no definite lesion around the previous operation site. Just 8 hours after the capsule endoscopy examination, a large amount of hematochezia, dizziness, and diaphoresis occurred, along with a decrease in hemoglobin level, from 9.7 g/dL to 6.9 g/dL. The patient did not take oral prednisolone during the 2 days of examination due to the unavailability of an oral intake state. Immediately after the detection of massive hematochezia, intravascular injections of 125 mg methylprednisolone sodium succinate per every 8 hours were started, and an emergency operation was prepared. Surprisingly, the hemoglobin increased to 10.7 g/dL with 3 packs of RBC transfusion, suggesting termination of the bleeding. Thereafter, the patient's hematochezia was undetected, and his hemoglobin remained stable. Five days later, the methylprednisolone sodium succinate injections were replaced with oral prednisolone treatment, 60 mg per day for 2 days, which was to taper down over a two-week period. The patient has been asymptomatic for 15 months with no medical therapy.

Coronal reformation computed tomography (CT) image shows segmental wall thickening and dilatation of the small bowel (black arrows), mesenteric edema (white arrows), and focal fluid collection in the adjacent peritoneal cavity (arrowhead).

(A) Histologic findings of ileal lesion show diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells from submucosa to subserosa (H&E stain, ×40). (B) A large sheet of mature eosinophils with edema fluid is visualized in the high power field (H&E stain, ×400).

DISCUSSION

The etiology of eosinophilic gastroenteritis is unknown, and a definitive pathologic mechanism has not been elucidated. Instead, it is likely that eosinophilic gastroenteritis is not a single entity, but rather a heterogenous collection of disorders--with varied causes, but with similar clinicopathologic features9). Allergic phenomena, particularly food sensitivity, have been proposed, but the evidence for this is limited. Although food hypersensitivity (usually to milk) may be found in children with eosinophilic gastroenteritis, the response to dietary elimination is usually disappointing. However, eosinophilic ileitis with perforation can be caused by Angiostrongylus (parastrongylus) costaricensis5), and eosinophilic ileocolitis by Enterobius vermicularis10), suggesting an allergic pathogenesis. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is generally considered to be a chronic benign disease, but there have been several reports of fatal outcomes11, 12).

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is categorized according to three distinct forms (mucosal, mural, and serosal) based on its dominant location in the gut wall13). In the mucosal type, the injury is concentrated in the mucosal layer. In this case, the condition behaves like other forms of inflammatory bowel disease, with diarrhea, cramping, postprandial nausea, vomiting, and periumbilical pain. The mural type is characterized by the localization of tissue injury and inflammatory reaction with abundant eosinophils in the submucosa and muscularis propria. In this case, the clinical presentation consists of intestinal obstruction, with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and distension. The serosal type, which is the rarest form, is characterized by diffuse eosinophilic infilatrates of the gut serosa, and may be associated with eosinophilic ascites. If the eosinophilic infiltration is extensive, there may also be malabsorption, weight loss, enteropathy with protein loss, blood loss, and anemia14).

In our case, the initial relevant site was the submucosa and muscle layer in the distal ileum, which is consistent with mural type, and explaining both the obstruction symptoms, and the CT finding of segmental small bowel wall thickening. However, the abdominal pain, reoccurring 17 days after the operation, subsided following moderate doses of steroids, suggests another eosinophilic enteritis-related small bowel involvement. Furthermore, the capsule endoscopy showed multiple hemorrhagic spots throughout the proximal jejunum, and spurting of fresh arterial bleeding in the mid-to distal jejunum, far from the anastomotic site. There was no definite ulcer, mass, or vascular abnormality, and this bleeding was rapidly controlled by high-dose injections of steroid, indicating that it was a manifestation of jejunal eosinophilic enteritis, the first bleeding case visualized by capsule endoscopy so far. This spurting of fresh arterial bleeding suggests that eosinophilic enteritis can be fatal if it is not rapidly controlled, as it was in our case.

The diagnosis of eosinophilic enteritis is a rather difficult one, especially when it presents as abrupt obstruction, perforation, or bleeding, especially in the small bowel. Most diagnoses are made retrospectively and histopathologically, as in our case. If there is a high degree of suspicion of eosinophilic enteritis for a patient with ill-defined abdominal pain, coupled with nonspecific laboratory results and inconclusive radiologic findings, laparoscopy, instead of laparotomy, can be tried for a full-thickness biopsy of the intestine15-17). Recently, wireless capsule endoscopy has been shown to be useful in the diagnosis of small bowel disease, which is beyond the reach of standard upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. Maybe the combined approach of capsule endoscopy for localization of lesion, and laparoscopy for the biopsy can facilitate the early diagnosis of eosinophilic enteritis, hence early steroidal treatment.

We report a case of eosinophilic enteritis, presenting as a small bowel obstruction, followed by severe jejunal bleeding, which was visualized by capsule endoscopy. This case suggests that if there are symptoms of eosinophilic enteritis, such as abdominal pain, a period of high-dosage steroid therapy is mandatory, in order to prevent further occurrences of complications such as fatal bleeding.