Endoscopic Sphincteropapillotomy: An Analysis of 108 Cases

Article information

Abstract

Since 1976, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has been done in 1,618 cases at Kwangju Christian Hospital in Kwangju, Korea. Between November 1981 and September 1984, endoscopic sphincteropapillotomy (EST) was performed on 108 patients. The results are as follows:

Common bile duct stones were found in 98 of the patients (including 7 patients on whom T-tube cholangiography was done), ascaris in the common bile ducts of 6 of the patients, fibrotic stenosis of a periampullary choledochoduodenal fistula in 1 of the patients, and impacted stones in the ampulla of Vater in 3 of the patients (a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography was also done on these 3 patients).

In the case of 5 of the patients stones were extracted under direct vision, in the case of 39 of the patients stones passed in the stool, and in the case of 31 of the patients stone elimination was confirmed on repeated ERCP or T-tube cholangiography. In the case of 26 of the patients, small stones were removed, large stones remained and symptoms and laboratory findings showed improvement.

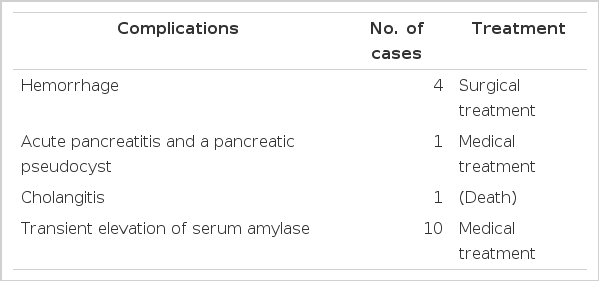

As complications after EST, bleeding developed in 4 patients, acute pancreatitis with a pancreatic pseudocyst developed in 1 patient, and another patient died of sepsis following cholangitis.

The overall success rate was 93.5%; morbidity rate, 5.6% and the mortality rate, 0.9%.

INTRODUCTION

Recently, in gastroenterology endoscopy has developed so much that endoscopic procedures are widely employed in the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the entire digestive system. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is popularly used in the diagnosis of diseases of the pancreas and the biliary system.1–3) As the anatomy and pathology of these organs became increasingly clearly defined and the biliary system could be approached with an instrument threaded through an endoscope, several trials were noted in the development of techniques of endoscopic biliary operations.4–8) Endoscopic sphincteropapillotomy (EST) is a therapeutic step above ERCP. In EST, the ampulla of Vater is incised with a high-frequency electric wave, and adequate drainage from the common bile duct is permitted. EST was developed by Demling and Classen5) in West Germany, and by Kawai and his coworkers1,9) in Japan. Since it was performed successfully in humans for the first time in 1973, it has contributed much to the treatment of benign papillary stenosis and common bile duct stones. At present, it is widely performed in Western Europe,5,10) Japan4,11) and the United States.12–14)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Materials

The subjects were 108 inpatients in a male to female ratio of 1:2.2, the majority of whom were in the 5th to 7th decades of life (ranging from 16 to 83 years of age) (Table 1), who had been diagnosed as having a variety of biliary-pancreatic diseases (Table 5).

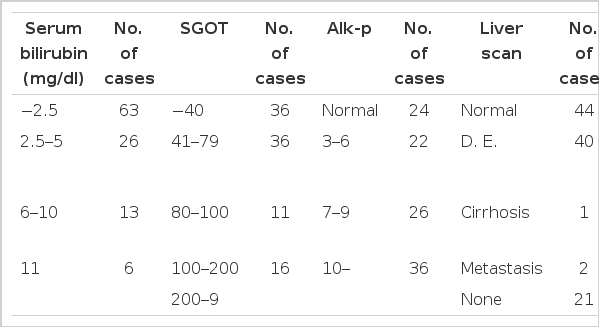

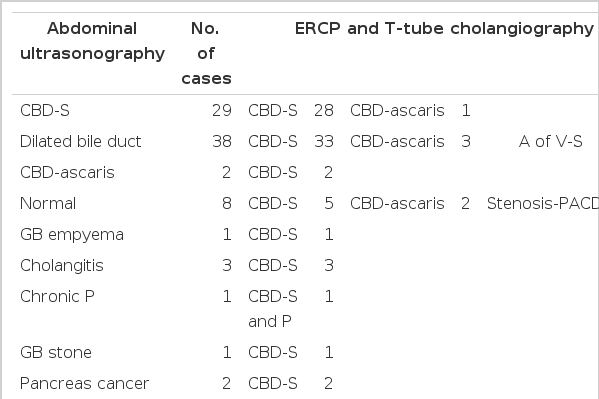

Epigastric pain was the presenting symptom in the majority of patients. Jaundice and fever were also noted. The duration of chief complaints was variable from days to decades (Table 2). According to the past histories, cholecystectomy had been performed on 34 patients, seven of whom had T-tubes, but no one had undergone Billroth II gastrectomy. The serum bilirubin level was high in 45 patients, and the serum alkaline phosphatase level in 84 patients (Table 3). ERCP was done on 103 patients, T-tube cholangiograpny on 7, and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography on 4 (Table 5). Liver scan, abdominal ultrasonography, and abdominal CT were also helpful in the diagnosis (Table 4).

2. Methods

Patients were prepared in the same manner as for ERCP.15) All of the patients were admitted to the hospital and given routine laboratory tests, including coagulation profiles, and two or three units of blood were crossmatched for each, for use in case of bleeding. The papillotome was inserted accurately into the common bile duct. A cutting bow was made to be used with a pulling motion. The sphincter of Oddi was incised with an electric knife which was applied to the 11 to 12 o’clock sector of the ampulla of Vater (The electric current was applied intermittently for 3 to 4 seconds). The length of the incision depended on the diameter of the common bile duct. It was about 10 to 15mm. In the case of five of the patients, stones were extracted with a Dormia basket under direct visualization. EST was finished in no more than 30 minutes. After EST, no food was allowed the patient, and we observed him or her carefully for the following 24 hours, when most of the complications are likely to develop.16) Seven to ten days later, ERCP was repeated in patients who were suspected of having residual stones. When stones were definitely present, EST was repeated, To confirm the efficacy of EST, we followed the patients with such work as ERCP, liver function tests, serum amylase.

RESULTS

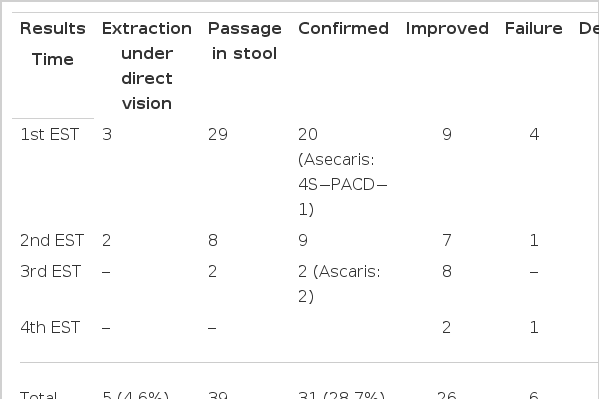

1. Efficacy and Findings of EST (Tables 6 and 7)

In 65 patients, EST was done once, and in 3 patients, four times. Stones were extracted under direct visualization in the case of 5 patients, they were found in the stool in the case of 39 patients, and stone elimination was confirmed by repeated ERCP or T-tube cholangiography in the case of 31 patients. In 75 (69.4%) of 108 patients, stones were removed completely. In 26 patients, not all of the stones were removed, or improvement was noted only in the symptoms and liver function tests. EST was performed with success in 101 patients, 93.5% of them all.

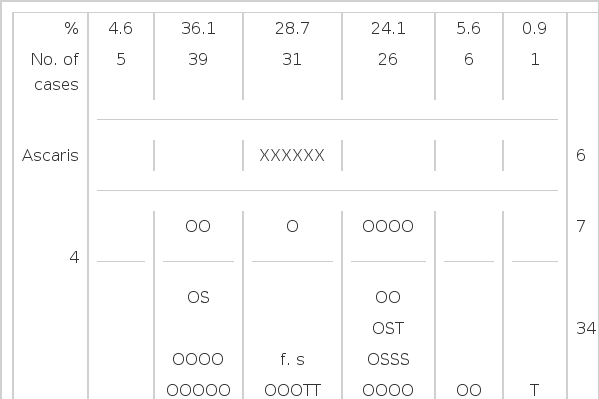

Table 7 shows the size and number of stones which were extracted under direct visualization, passed in the stool, or were found to have been removed at ERCP or T-tube cholangiography. Most stones were 20 to 30mm in size. In each of 69 cases, only one stone was found. Mixed stones were found in most patients. In two of the six cases with common bile duct ascaris, ascarides were seen which had migrated long before and become adhered to the wall of the common bile duct.

Of the 7 unsuccessful cases, in 4 there was bleeding from the site of the EST; in one, a large periampullary diverticulum and in another, fibrotic papillary stenosis. These could be treated with surgical operations, but in one patient, EST failed due to cholangitis and sepsis. Of the above mentioned causes of failure, bleeding and cholangitis may also be considered as complications after EST.

DISCUSSION

EST, as a therapeutic branch of ERCP,16) was performed successfully on a human for the first time in 1973.17) In the past, common bile duct stones were treated surgically, in most cases. At present, EST, a noninvasive therapeutic procedure, has largely replaced surgery and is used worldwide.5–8) As time goes on, it is indicated in more cases and its technique is being developed further, making it easier to use.

The major indication18) for its use is common bile duct stone. In our study, common bile duct stones were present in 93.5% of the 108 cases, which was comparable to 76% in Safrany’s,19) and to 93.5% in Liguori’s.18) The indications14,16) which are accepted, as based on experience, are (1) recurrent or residual stone(s) following cholecystectomy, (2) choledocholithiasis in high-risk surgical patients, (3) benign papillary stenosis, (4) malignant tumors of papilla, and (5) gallstone pancreatitis.14,16,20,21)

When there is a T-tube left in place following cholecystectomy,20) an irrigation through the tube, chemical dissolution with mono-octanoin, or mechanical extraction using a basket can be tried. The last is widely employed with a success rate of 95%.22,23) Recently, mechanical extraction has been tried, using a small-caliber choledochal fiberscope along the T-tube tract.24) When these methods fail, the patient should undergo an operation or EST; the latter is preferable in a high-risk patient.20,25) When there is no tube left in place (27 cases in our study), EST is indicated in elderly or high-risk patients14,16,26) and is considered to be a reasonable alternative to surgery in young and low-risk patients.20)

EST is an excellent method for the relief of a bile flow obstruction in patients with gallbladder in situ, but the risk of cholangitis is greater and cholecystitis may occur within 6 months after EST. In this situation, an operation is necessary.27) At present, EST is popular as a safer method than a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in patients with jaundice due to gallstones, or than an emergency operation in those with acute illnesses such as cholangitis28) or pancreatitis.21) After these acute illnesses subside, an elective cholecystectomy can be done with low risk. It is an especially suitable course of action to take in the case of high-risk or elderly patients.16,26)

In benign papillary stenosis,14,18) EST is indicated but stenosis should be confirmed prior to EST. Recurrent epigastric pain, laboratory findings of biliary stasis, histological findings on liver biopsy compatible with extrahepatic obstruction, and, rarely, symptoms of pancreatitis are seen. With ERCP we can see the dilated common bile duct and, sometimes, the dilated pancreatic duct. Delayed drainage of contrast material from the common bile duct (longer than 45 min) with the patient in the supine position is characteristic of papillary stenosis. With the use of manometry during the ERCP, elevated pressure of Oddi’s sphincter is often confirmatory.29) In one report,16) only 17 of 31 patients diagnosed as having papillary tenosis and followed for 1 to 5 years were satisfied with the results of EST. Moreover, EST for papillary stenosis may be more hazardous than EST for stones.

In patients with biliary obstruction due to malignant tumors of ampulla of Vater, adequate drainage can improve the general conditions of patients prior to surgery. In patients who are elderly or in poor general condition and have metastases to the liver, only EST permits effective long-term palliation. A small EST can be done for easy passage of a large catheter. Some therapeutic maneuvers, such as stone extraction, insertion of guide wires, and even laser treatment of tumors may be technically easier when done under direct vision. Attempts are being made, therefore, to pass fiberscopes through the mouth directly into the bile duct.16) Cremer29) tried to use a fiberscope for the removal of stones in Wirsung’s duct.

The contraindications for EST14,18) include blood coagulation disorders, a long stricture of the distal common bile duct, and acute pancreatitis. Recently, a special balloon catheter was tried for dilation of the stricture.30,31) The cases in which EST should not be performed or fails frequently18) are those with intradiverticular papillae or large stones (>2.5cm).14,32) However, it has been reported that EST could be done without complications18) on patients with papillae in the floors or rims of diverticula. The cases with large stones comprise the majority of failures in EST.33) However, even giant stones may pass spontaneously.34) In our study, large stones passed spontaneously in 21 cases: stones larger than 3cm in diameter passed in the stools in 13 cases, and stone removal was confirmed on repeated ERCP in 8 cases. For the removal of the large stones, chemical dissolution using mono-octanoin33) and electrohydraulic lithotripsy have been tried, but these measures have not been widely accepted due to the complications and technical problems accompanying them.35) Recently, there has been a report that since the invention of a mechanical lithotriptor.33,36,37) the rate of successfully extracting common bile duct stones may have increased to 97%.33)

In our study, stones were extracted under direct vision in 4.6% of the cases and found in the stool in 36.1%. In Safrany’s report of 3,070 cases,38) passage of stones in the stool was noted in 58.5%, mechanical extraction was used in 32.0%, and failures were the result in 9.5%. These contrasted much with our results. In our study, the success rate of EST was 69.4%, considering 31 cases in which stones not passed in the stool were found to have been eliminated at repeated ERCP and T-tube cholangiography. The success rate increased to 93.5%, considering the fact that in 26 cases in which stones were not removed completely, symptoms and laboratory findings showed improvement. According to many large series,16) EST is technically successful in over 95% of the attempts to use it, and the overall success rate for the procedure is in excess of 90%, Good cooperation wiyh surgeons, routine laboratory tests including coagulation profiles, preparation for emergency transfusion, and adequate antibiotics are necessary for the successful employment of EST.14) EST failure is usually due to inexperience, difficult access (large diverticula, Billroth II gastrectomy), or large stones.16) Although EST has many advantages and draws much support, it is technically difficult and requires a high degree of skill and much experience with doing the ERCP procedure.14,20) In patients who have undergone a Billroth II gastrectomy,39,40) it is very difficult to do EST, and many complications ensue due to anatomic alteration and the inadequate control of a papillotome. To date, the success rate has been reported to be 50 to 80%.39,40) However, the rate is increasing with the use of improved techniques and several types of special endoscopes.

The complications following EST include bleeding, cholangitis, pancreatitis, retroperitoneal perforation, and impacted stones. In Table 941) is shown the morbidity and mortality rates for EST and for emergency operations. In our study, the morbidity was 5.6%, and the mortality, 0.9%. These are similar to Safrany’s figures.41) Other investigators14,42) report similar morbidity and mortality rates: 7 to 10% and 0.4 to 1.4%, respectively. In contrast to these, McSherry and Glenn43) performed choledocholithotomy in 341 cases of recurrent and residual common bile duct stones with a mortality rate of 2.1%. In a report on 5,815 patients who had undergone surgical sphincterotomies44) the average mortality rate given was 4.74%. Crepsi and his coworkers45) reported a high mortality rate of 13.3% in repeat operations for common bile duct stones in elderly patients (65 to 84 years of age). These show that EST is a safer method than surgery for recurrent common bile duct stones in elderly patients.

Bleeding is the most frequent and dangerous complication and it easily occurs with a long (>20mm)46) or with repeated incisions for the extraction of giant stones. Most cases of minor bleeding can be treated conservatively. However, bleeding from major arteries rarely occurs. When it does, it, of course, requires an emergency operation. In about 25% of the patients, a retroduodenal artery passes anteriorly to the distal common bile duct and major bleeding requiring an operation develops when this artery is cut.18)

Pancreatitis develops due to heat injury resulting from the use of electric wave for a long time, displacement of a papillotome, or stasis of pancreatic juice caused by a stone.47,48) Pancreatitis can be prevented somewhat with the accurate placement of an electric knife.

Cholangitis18) may develop due to infection following cannulation or duodenocholedochal reflux through a papilla which does not permit adequate drainage due to an inadequate incision. In these cases, adequate drainage of bile and administration of antibiotics can be accomplished through a nasobiliary drainage catheter, but surgical intervention is at times required. To prevent cholangits, we administered antibiotics before and after EST.

Retroperitoneal perforation18) can be differentiated from acute pancreatitis by the findings of retroperitoneal air or leaked contrast material in abdominal films. It develops due to a choledochoduodenal disconnection following a wide EST and can be controlled with medical treatment. When there are residual stones, biliary drainage should be undertaken.

Other complications of EST16) include the impacting of stones in the incised orifice, which could occur during the removal of large stones or with the use of a Dormia basket. With an intact gallbladder, cholecystitis may develop, but it can be prevented with antibiotics.

Concerning the long-term results of using EST, Safrany and his coworkers49) reported no symptoms in 93% of patients, restenosis in less than 1%, and recurrent stones despite good biliary drainage in 2% for 7 years following EST. In contrast to these good results, one group16) reported papillary stenosis and recurrent stones in 5 to 10%. Whether these problems are more frequent and serious than the recurrence following surgical operations is not clear and requires further study. Since our patients were few in number and were followed for a short time only, we will follow these problems with much interest.