|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 23(1); 2008 > Article |

|

Abstract

We describe here the case of a 39-year-old woman with a cortisol-producing adrenal adenoma and she presented with endometrial hyperplasia and hypertension without the specific characteristics of Cushing's syndrome. The patient had consulted a gynecologist for menometrorrhagia 2 years prior to her referral and she was diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia and hypertension. Her blood pressure and the endometrial lesion were refractory despite taking multiple antihypertensives and repetitive dilation and curettage and progestin treatment. On admission, the clinical examination revealed mild central obesity (a body mass index of 22.9 kg/m2, a waist circumference of 85 cm and a hip circumference of 94cm), but there was no hirsutism and myopathy. She showed impaired glucose tolerance on an oral glucose tolerance test. The biochemical hypercortisolemia together with the prolactin and androgen levels were evaluated to explore the cause of her anovulation. Adrenal Cushing's syndrome was confirmed on the basis of the elevated urinary free cortisol (454 µg/24h, normal range: 20-70) with a suppressed ACTH level (2.0 pg/mL, normal range: 6.0-76.0) and the loss of circadian cortisol secretion. A CT scan revealed a 3.1 cm, hyperechoic, well-marginated mass in the left adrenal gland. Ten months post-adrenalectomy, the patient had unintentionally lost 9 kg of body weight, had regained a regular menstrual cycle and had normal thickness of her endometrium.

The prevalence of obesity and its related disorders is rapidly increasing with increasing economic development and the growing convenience of modern life, but obesity and weight gain can also be caused by drugs and several endocrine disorders such as Cushing's syndrome. Cases of mild or subclinical Cushing's syndrome are increasingly being reported owing to emerging concerns about health problems and the developments of image technology1). Cushing's syndrome is well characterized by central obesity, proximal muscle weakness, bruising, violet striae, menstrual irregularities and hirsuitism. Obesity, especially central obesity, is also associated with metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other disorders that present with menstrual irregularities, including endometrial hyperplasia. Clinicians must stay alert for the possibility of secondary causes of menstrual abnormalities in patients with recent weight gain to formulate a correct diagnosis.

In this report, we describe the case of a 39-year-old woman with a cortisol-producing adrenal adenoma that presented as refractory endometrial hyperplasia and hypertension, and she was without any of the remarkable, specific characteristics of Cushing's syndrome.

A 39-year-old woman had been previously diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia and hypertension, and she was referred to our department for further evaluation and management of persistent menometrorrhagia despite being treated with progestin and ten dilatation and curettage procedures in 2 years. Her past medical history was negative for diabetes mellitus, but positive for hypertension. She had been treated with antihypertensive medication for 2 years, but her blood pressure control was not satisfactory. The patient had gained 7 kg in body weight over the past 4 years. The patient had delivered two children vaginally without complication, at the ages of 25 and 28, respectively, and she had a negative history of spontaneous or elective abortion. She was a former nurse and denied using alcohol.

At the time of her referral, her blood pressure was 155/92 mmHg. She presented with mild central obesity (waist to hip ratio, 0.90); her weight was 60 kg, and her BMI was 22.9 kg/m2. No violet striae, proximal myopathy, hirsutism or acne were observed, but minor bruising was present on her forearm (Figure 1).

Her hormone levels during the early follicular phase, which had been determined 2 years earlier upon a previous visit to a local clinic for abnormal uterine bleeding prior to her referral, were LH: 3.2 mIU/mL (normal range: 2.0-15.0 mIU/mL), FSH: 6.6 mIU/mL (3.0-20.0 mIU/mL), estrone (E1): 15.0 pg/mL (1.5-15.0 pg/mL) and estradiol (E2): 6.3 pg/mL (20.0-145.0 pg/mL). However, her progesterone level was very low at 0.2 ng/mL (3.0-20.0 ng/mL), suggesting chronic anovulation and dysfunctional uterine bleeding. At that time, the results of a thyroid function test, a prolactin level test, a liver function test and the platelet count were all within normal ranges.

Other biochemical laboratory tests gave the following results: protein, 7.1 g/dL (6.0-8.1 g/dL), albumin: 4.2 g/dL (3.2-5.3 g/dL), cholesterol: 149 mg/dL (120-220 mg/dL), LDL-cholesterol: 100 mg/dL (0-130 mg/dL), HDL-cholesterol: 45mg/dL (35-80 mg/dL), triglyceride: 79 mg/dL (35-200 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase: 66 IU/L (39-120 IU/L) and creatinine: 0.9 mg/dL (0.5-1.1 mg/dL). An oral glucose tolerance test indicated impaired glucose tolerance (fasting glucose: 74 mg/dL, 2-h: 187 mg/dL).

Ultrasonography showed a 15.6 mm thickness of the endometrium. Endometrial biopsy revealed simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia. Ultrasonography revealed a 2.5 cm size simple cyst on the left ovary; otherwise, the architecture of both ovaries was normal.

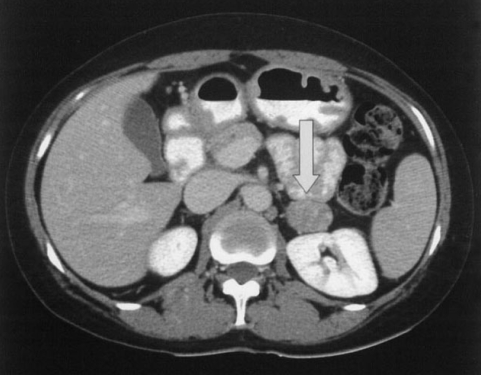

Although she did not present with the typical features of Cushing's syndrome, we ordered laboratory tests for cortisol and ACTH as well as the sex hormone, gonadotropin and prolactin levels to investigate the cause of her chronic anovulation and the persistent menstrual irregularity. The results were 24-h urine free cortisol: 454.5 µg/24h (20.0-70.0 µg/24h), serum ACTH: 2.0 pg/dL (6.0-76.0 pg/dL) and midnight serum cortisol: 15.3 g/dL (0-10.0 µg/dL); this all suggested hypercortisolemia and loss of the circadian rhythm. The 24-h urine free estrone and free estradiol levels were 3.3 g/24h (2.0-39.0 µg/24h) and 1.9 µg/24h (1.0-23.0 µg/24h), respectively. The E1/E2 ratio was elevated in the serum and urine (2.4 and 1.7, respectively). The serum testosterone was below the detectable range of 0.10 ng/mL. A CT scan revealed a 3.1-cm, hyperechoic, well-marginated mass in the left adrenal gland (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed as a cortisol-producing adrenal adenoma and she underwent a left adrenalectomy. During the 10-months follow-up, her hormonal laboratory tests were 24-h urine free cortisol: 45.9 µg/24h, serum ACTH: 61.9 pg/dL and serum cortisol: 15.3 µg/dL. The serum estrone and estradiol levels were 38.00 pg/mL and 40.45 pg/mL, respectively, and the 24-h urine free estrone and free estradiol levels were 2.0 µg/24h and 1.1 µg/24h, respectively. The E1/E2 ratios in the serum and the 24-hour urine were 0.9 and 1.8, respectively. She showed a gradual and unintentional loss of 9 kg of body weight. Her waist to hip ratio was decreased from 0.90 to 0.78, and she regained regular menstrual cycles. Her blood pressure was well controlled by a half dose of the previous medication after adrenalectomy. Endometrial hyperplasia, as determined by ultrasonography, was not seen thereafter.

The patient in this case was referred to us for the evaluation of the recurrent endometrial hyperplasia that was not resolved by repeated therapeutic curettage and progestin treatment for 2 years, and she was finally diagnosed with a cortisol-producing adenoma. After left adrenalectomy, her uterine lesion and menstrual abnormality completely resolved, and she experienced unintentional weight loss. Patients with Cushing's syndrome almost always show insulin resistance that's attributable to chronic hypercortisolism, which is frequently accompanied by metabolic syndrome and PCOS, and rarely by endometrial hyperplasia2). It is known that PCOS and anovulatory cycles can be caused by insulin resistance. In addition, it has been suggested that menstrual irregularity might result from hypercortisolemic inhibition of gonadotrophin release at the hypothalamic level rather than being caused by elevated levels of circulating androgen3, 4). It was proposed that hypercortisolemia could suppress pulsatile LH secretion by inhibiting pituitary responsiveness to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)5). However, the mechanisms of the occurrence of endometrial hyperplasia in these patients are poorly understood, and to the best of our knowledge, there are no other cases in the literature of Cushing's syndrome presenting as endometrial hyperplasia. Although our patient presented with metabolic syndrome and minor bruising, these signs were not accompanied by any obvious clinical features of Cushing's syndrome.

Although we confirmed chronic anovulation and Cushing's syndrome in this patient, an inappropriately low level of serum estradiol had been found by a local clinic 2 years prior to her referral, suggesting hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism as the cause of her menstrual disturbance, which was in contrast to the elevated LH levels that are usually observed in patients with PCOS. Continuously elevated cortisol inhibits the activity of 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and it might prohibit the action of progesterone in the uterus as well as the secretion of GnRH from the thalamus6). In this patient, these hormonal changes finally resulted in a functional and absolute progesterone deficiency and recurrent endometrial hyperplasia, irrespective of repetitive curettage and progestin treatment.

Given that the cortisol receptor has not been demonstrated in the uterine stromal or endometrial cells, the possibility seems remote that chronic excess cortisol alone induced the endometrial hyperplasia. Rather, based on the fact that both insulin receptors and IGF-1 receptors are expressed in endometrial cells7, 8), we suggest that the hyperinsulinemia induced by excess cortisol in this patient could have been an additive factor for the development of endometrial hyperplasia. It has been suggested that insulin resistance or hyperinsulinemia in patients with PCOS increases the production of androgens in the theca cells and this augments aromatase activity in adipocytes, thereby increasing the conversion to estrone and the LH level. Our patient showed an elevated E1/E2 ratio in both the serum and urine (2.4 and 1.7, respectively), indicating increased production of estrone in the peripheral tissues. In contrast, the androgen and LH determinations in her serum revealed a low estrogen level that was attributable to the inhibitory effects of hypercortisolemia on the thalamus and ovaries.

Our patient presented with chronic anovulation and endometrial hyperplasia, and she was found to have Cushing's syndrome; she experienced complete resolution of her uterine lesion and cardiometabolic abnormalities after removal of a left adrenal tumor. This case demonstrates the necessity of performing endocrine tests, including urinary free cortisol measurements, in young women with endometrial hyperplasia and anovulation even when these patients do not show the typical features of Cushing's syndrome.

Notes

This work was supported in part by the foundation for Gyeongsang National University Hospital.

References

1. Ross NS. Epidemiology of Cushing's syndrome and subclinical disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1994. 23:539–546PMID : 7805652.

2. Kaltsas GA, Korbonits M, Isidori AM, Webb JA, Trainer PJ, Monson JP, Besser GM, Grossman AB. How common are polycystic ovaries and the polycystic ovarian syndrome in women with Cushing's syndrome? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000. 53:493–500PMID : 11012575.

3. Dubey AK, Plant TM. A suppression of gonadotropin secretion by cortisol in castrated male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) mediated by the interruption of hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone release. Biol Reprod 1985. 33:423–431PMID : 3929850.

4. Breen KM, Billings HJ, Wagenmaker ER, Wessinger EW, Karsch FJ. Endocrine basis for disruptive effects of cortisol on preovulatory events. Endocrinology 2005. 146:2107–2115PMID : 15625239.

5. Breen KM, Karsch FJ. Does cortisol inhibit pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion at the hypothalamic or pituitary level? Endocrinology 2004. 145:692–698PMID : 14576178.

6. Karalis KP, Goodwin G, Majzoub JA. Cortisol blockade of progesterone: a possible molecular mechanism involved in the initiation of human labor. Nat Med 1996. 2:556–560PMID : 8616715.

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

Budd-Chiari syndrome presenting with abdominal wall varices2020 September;35(5)

A case of mediastinal ectopic thyroid presenting with a paratracheal mass2013 May;28(3)

A case of secondary syphilis presenting as multiple pulmonary nodules2013 March;28(2)

Parathyroid Carcinoma Presenting as a Hyperparathyroid Crisis2012 June;27(2)

A Case of Gastric Adenocarcinoma Presenting as Meningeal Carcinomatosis2007 December;22(4)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print