INTRODUCTION

A biloma is a rare abnormal accumulation of intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile caused by traumatic or spontaneous rupture of the biliary tree1, 2). It is most commonly caused by surgery, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD), and abdominal trauma11, 12). A spontaneous occurrence of a biloma is a very rare condition. We report here a patient who complained of chills, fever and right upper quadrant abdominal discomfort. The patient was diagnosed with a biloma due to a spontaneous intrahepatic biliary rupture.

CASE REPORT

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with her guardian, with acute fever and chills that developed the day before admission. She had severe marasmus and complaints of abdominal discomfort. There was no history of trauma or hepatobiliary disease. The patient was diagnosed with diabetes a few years previously, but this was not being treated. The history included a cerebral infarct six years prior to presentation. She denied alcohol use. The patient had a 30-pack year cigarette smoking history. The patient's father had a history of cerebral infarct and hypertension.

On admission to the emergency room, the vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 70/40 mmHg, heart rate 118/min, respiratory rate 30/min and temperature 40.3Ōäā. The patient appeared to be in acute distress; she was lethargic, the sclerae were slightly yellow and the conjunctivae were pale. The thoracic auscultation revealed rhythmic heartbeats and clear respirations. The abdominal examination revealed slight tenderness in the right upper quadrant, but there was no palpable mass. The remainder of the examination was within normal limits. The laboratory studies were as follows: WBC 52,400/mm3, Hb 12.3 g/dL, platelets 90,000/mm3, AST 153 IU/L, ALT 135 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 255 IU/L, total bilirubin 2.07 mg/dL, total protein 5.9 g/dL, albumin 3.0 g/dL, BUN/Cr 25/1.9 mg/dL, ESR 25 mm/hr, and CRP 20.4 mg/dL. The serum electrolyte levels were normal except for an elevated potassium 7.0 mmol/L. The AFP and amylase were in normal ranges. The PT (15.9 sec) and PTT (47.3 sec) were elevated. The ABGA data were as follows: pH 7.24, PaO271 mmHg, PaCO2 19 mmHg, HCO3 15.1 mmol/L and SaO2 90.0%. The hepatitis viral marker tests, including HBsAg, anti-HBs Ab and anti-HCV, were all negative.

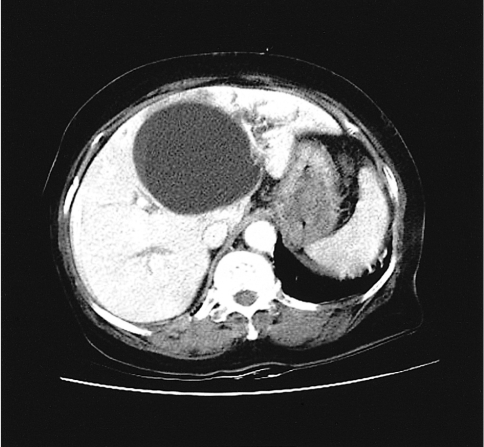

Standard X-rays on the day of admission revealed lung infiltrates and no specific findings in the abdomen. The abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 9.5├Ś8.5 cm subcapsular cyst with a clear boundary in the left hepatic lobe and enlargement of the intrahepatic bile duct around the cyst. Although the left hepatic lobe had some atrophic findings, there were no significant signs of an enlarged bile duct or abnormal gallbladder (Figure 1).

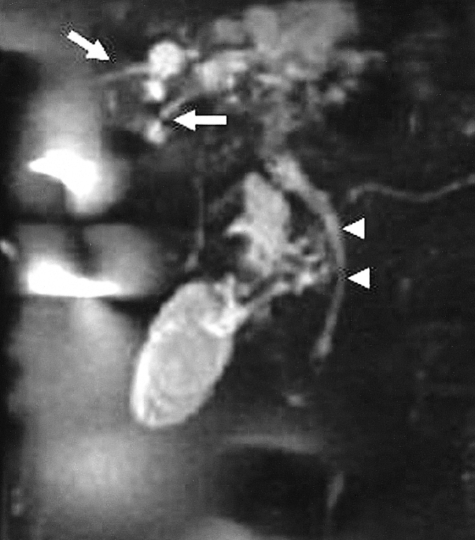

On the day of admission after the computed tomography, the blood pressure was 70/40 mmHg and voluntary respirations decreased. The ABGA revealed a pH 7.05, PCO2 64.8 mmHg, PO2 73.3 mmHg, HCO3 17.9 mmol/L and SaO2 87.4%, which indicated hypoxemia. The patient was intubated and put on a respirator; she was treated with antibiotics and vasopressors. On the second day of admission, percutaneous drainage with an 8.5 Fr pigtail catheter, under the guidance of an abdominal ultrasound was performed for diagnosis and treatment. We removed 565 mL of fluid that was dark brown in color. For a diagnosis, biochemical tests were carried out on the bile, and these tests revealed a total bilirubin of 22.3 mg/dL and a direct bilirubin of 18.9 mg/dL. The leukocyte count was 4,560/mm3, and gram staining showed a gram negative bacillus. On the third day of admission, her vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 100/65 mmHg, heart rate 110/min and temperature 37.2Ōäā. There was 200 mL of drained bile, the s-fibrinogen was 894 mg/dL (200-415), the D-dimer was 9,040 ng/mL (0-255), and the FDP was elevated up to 97 ug/mL (normal range: 0-5). On the eighth day of admission, the patient's mental status improved, the vital signs were stable and voluntary respirations recovered. The patient was taken off the respirator and extubated. E.coli was isolated from the bile and blood samples. On the thirteenth day of admission, pancreatico-biliary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a biloma that was connected to the intrahepatic bile duct (Figure 2). On the sixteenth day of admission, the biloma that was connected to the intrahepatic duct and common bile duct was noted again via a tubogram performed with a catheter.

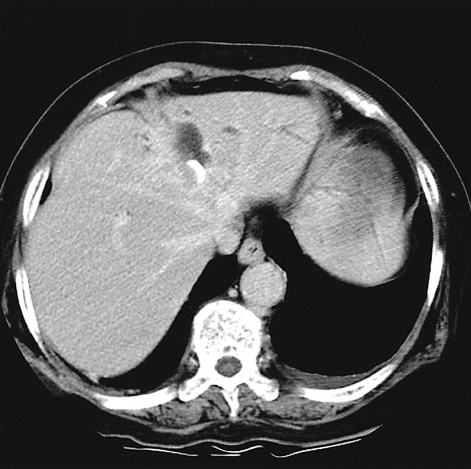

Over time, the amount of bile drainage decreased. On the twentieth day of admission, 64 mL of bile was drained, the leukocyte count was 340/mm3 and there were no signs of bacteria on culture or gram staining of the bile. The follow-up CT showed that the size of the cyst had decreased to 5.4├Ś4.6 cm and the density around the cyst had increased. The amount of drainage did not decrease afterward, and the connection between the biloma and the bile duct was still noted. On the 25th day of admission, the drainage tube was blocked and follow-up of the bilirubin in blood and the size of the biloma were assessed. On the 29th day of admission, follow-up CT showed a marked decrease in the size of the cyst (Figure 3), and the serum bilirubin was normal (0.22 mg/dL). On the 34th day of admission, the drainage tube was removed after evaluating the size and connection of the biloma via a catheter tubogram (Figure 4). The patient has been carefully monitored since discharge.

DISCUSSION

Gould and Patel reported the first case of a blioma in 19791). They reported a case with extrahepatic bile leakage after trauma to the upper right quadrant of the abdomen; the bile did not cause peritonitis, but it accumulated in an encapsulated form. This concept was later applied to all cases with biliary tract lacerations caused by bile leaks that formed a capsule inside or outside of the liver1). The mechanism of encapsulation is explained by a large amount of bile leaking at a fast pace that causes biliary peritonitis, or a small amount of bile leaking at a slow pace that causes mild inflammation. This leaked fluid is simultaneously trapped by the greater omentum and mesentery, where it becomes encapsulated2). Although the amount of bile leaked may be minor, the occurrence of an inflammatory reaction contributes to the appearance of a growth in size of the biloma3).

As diagnostic techniques continue to develop, more cases of biloma are being reported, but cases of spontaneous biloma and biloma accompanied by other diseases have rarely been reported to date. From 1979 to 1997, 25 cases of spontaneous biloma were analyzed by Fujiwara; the underlying causes included choledocholithiasis (16 cases), cholangiocarcinoma (2 cases), acute cholecystitis (1 case), liver infarction (1 case), hepatic abscess (1 case), nephrotic syndrome (1 case), obstructive jaundice (1 case), sickle cell anemia (1 case), and tuberculosis (1 case)4). In Korea, there have been two cases of choledocholithiasis accompanied by a biloma, and they were treated by nonsurgical methods5, 6). There is one report of a case of biloma after trauma7), and 1 case of a biloma after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)8). One of the patients with a choledocholithiasis who suffered a nontraumatic intrahepatic rupture of the bile duct, had a surgical repair9). The causes of biloma include trauma to the liver, which is the most common cause, abdominal surgery, endoscopic surgery and percutaneous catheter drainage10-13). Currently, the term biloma is generally used to describe intrahepatic or intraperitoneal focal biliary stasis14).

The clinical symptoms of a biloma are nonspecific, and they can range from no symptoms to abdominal pain and distention, jaundice and fever; leukocytosis can also be present15). In the case reported here there was no history of trauma, hepatobiliary tract examination or treatment. There were complaints of sudden chills, fever, upper abdominal discomfort and sensations of abdominal distention. Physical examinations showed tenderness in the upper right area of the abdomen, slight jaundice, hypotension, leukocytosis and fever over 40Ōäā. The size and location of the biloma are determined by the cause of the rupture of the bile duct, the location and speed of bile leakage and the rate the bile is reabsorbed by the peritoneum2). Fujiwara reported that the locations for bile leakage included the left hepatobiliary duct (8 cases), the gallbladder (5 cases), the right hepatobiliary tract (2 cases), the common bile duct (1 case), and unknown (9 cases); the locations where the bilomas formed were the left lobe (11 cases), the right lobe (10 cases), and the upper abdomen (4 cases). Vazquez analyzed 21 cases of biloma and found that 16 cases occurred in the upper abdominal area near the liver and five in the left upper abdominal area4).

The diagnosis of a biloma can be assisted by surgery, a history of trauma with abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal CT and MRI. A definite diagnosis can be made by a 99mTc-DISIDA scan, percutaneous aspiration or by ERCP1, 2). Abdominal ultrasonography shows a mass of low echogenicity with a clear border in the liver, and the follow up tests show changes in size16). The abdominal CT will give a more accurate view of the location of the biloma and show its relationship to the surrounding organs. A standard CT view will show a low-density mass in the liver at a CT number lower than 20. Ultrasonography and abdominal CT are sometimes unable to differentiate bilomas from seromas, lymphoceles and angiomas. MRIs or hepatobiliary scans can be useful when continuous bile leakage is present, but they are not diagnostic when continuous leakage is not present7, 17). Radiological image-guided aspiration tests, when testing for bilirubin, can be diagnostic18). When the aspirated substance is a clear yellow liquid, then microbiological tests must be done to rule out an infection. ERCP can be used to determine the location and severity of an active bile leak. However, the presence of small biliary cysts or bilomas, located in the lower areas of the liver that can be hidden by gastrointestinal shadows, can be difficult to diagnosis19).

We were able to identify a cystic lesion by abdominal CT; a tubogram and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) were used to confirm a bile leak from the common bile duct. The fluid obtained by the transabdominal ultrasonography assisted percutaneous cyst drainage containing 22.3 mg/dL of total bilirubin and 18.9 mg/dL of direct bilirubin; these findings confirmed the diagnosis of a biloma.

Treatment for bilomas that have a diameter of only a few centimeters is not always necessary; these lesions can be watched. However, most bilomas require treatment. In the past, surgery was the main approach to treatment. Currently, there are a much wider variety of options such as percutaneous catheter drainage, endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) and endoscopic drainage4, 6, 15, 19, 20). Surgery is now performed only in cases with a persistent bile leak or for treatment of underlying disease.

In this case, a spontaneous biloma with bacterial infection was found after the patient presented in septic shock. Transabdominal ultrasonography assistedpercutaneous drainage was performed and the patient recovered. After percutaneous drainage was performed, the amount of bile excreted did not decrease to lower than 64 mL per day. As there was no difficulty in flow through the common bile duct, the biochemical tests performed after removal of the drainage catheter showed no increase in total bilirubin or any increase in the size of the biloma, thus demonstrating a rare case of recovery.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print