To the Editor,

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) remains one of the most common infectious complications of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or solid organ transplantation (SOT). There have been many reports of CMV infection and/or disease in transplantation recipients and patients with AIDS. The risk of CMV disease occurring with chemotherapy has gradually increased with the use of more intensive chemotherapy in patients with hematologic malignancies [1]. In the non-allogeneic HSCT setting such as autologous HSCT or immunosuppressive therapy, including fludarabin, high-dose cyclophosphamide and steroids, and granulocyte infusions from unscreened donors are considered predisposing factors for CMV disease [1]. The lung and gastrointestinal tract are the major targets for CMV disease, and it can present throughout the entire intestine. Nevertheless, CMV appendicitis is exceedingly rare, and its clinical course and treatment are not well characterized. Only a few cases of CMV appendicitis have been reported in kidney transplantation recipients or patients with AIDS. We report a case of CMV appendicitis with concurrent bacteremia after consolidation chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

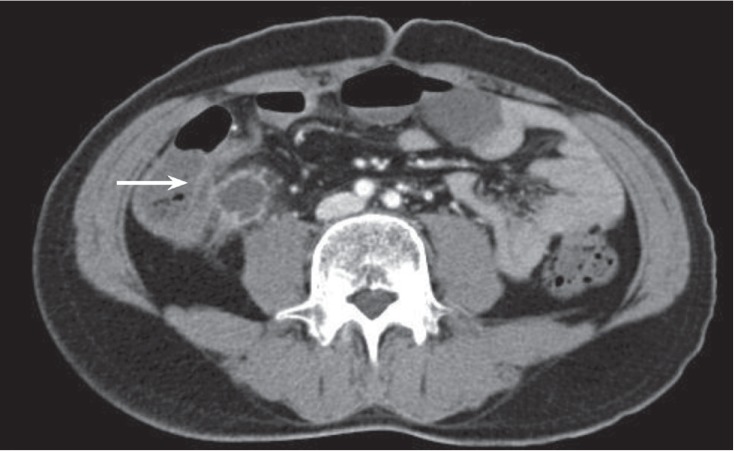

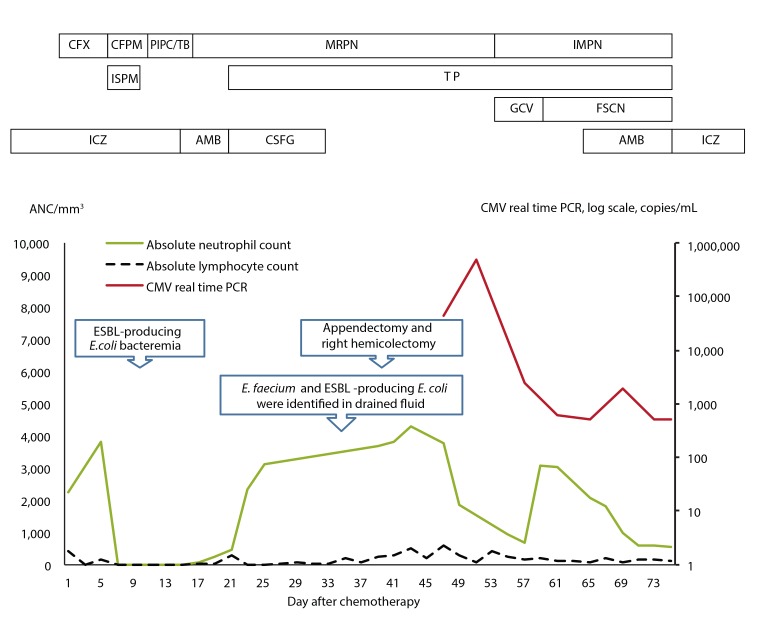

A 40-year-old male with precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia developed neutropenic fever and abdominal pain 9 days after starting consolidation chemotherapy (high-dose cytarabine 2 g/m2, every 12 hours, days 1 to 5; mitoxantrone 12 mg/m2, days 1 to 2). The patient had a history of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) and had been treated with itraconazole (400 mg/day) for more than 2 months. IPA was diagnosed according to the revised definition from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group Consensus Group. IPA had developed during the third cycle of induction chemotherapy, and serial regression of the lung lesion was evident. Empirical antibiotic therapy with cefepime (4 g/day) and isepamicin (400 mg/day) was started. On day 13 after starting chemotherapy, the patient's vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 120/70 mmHg, pulse rate 80 beats per minute, body temperature 37.7Ōäā. Abdominal examination revealed direct tenderness and rebound tenderness in the right lower quadrant. Chest examination revealed clear breathing sounds. Laboratory results revealed a white blood cell count of 10/mm3 (neutrophils 0%, lymphocytes 0%), hemoglobin 8.4 g/dL, platelets 26,000/mm3, aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase 24/39 IU/L, total/direct bilirubin 0.94/0.24 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine 12.8/0.67 mg/dL, total protein/albumin 5.3/3.3 g/dL, and C-reactive protein 19.78 mg/dL. The antibiotic therapy was changed to piperacillin-tazobactam (piperacillin 12 g/day, tazobactam 1.5 g/day) to broaden the coverage of anaerobic bacteria. Bacterial growth was detected in blood culture and identified as extended spectrum ╬▓-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli. Piperacillin-tazobactam therapy was withdrawn, and meropenem (3 g/day) was initiated. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed and revealed appendiceal wall thickening with a 2.4 ├Ś 2.1-cm hypodense lesion, suggesting appendicitis with periappendiceal abscess formation and microperforation (Fig. 1). There was no definitive bowel wall thickening at the terminal ileum and cecum. However, the patient was unable to tolerate surgical intervention due to persistent pancytopenia. Despite 6 days of antibiotic therapy the patient's fever was sustained with aggravation of his abdominal pain. On day 20, the patient's vital signs were: blood pressure 80/50 mmHg, pulse rate 170 beats per minute, and body temperature 38.6Ōäā. The patient subsequently developed septic shock. Teicoplanin (400 mg/day after the initial loading dose) was administered in addition to meropenem. A follow-up abdominal CT scan revealed hemoperitoneum and progression of appendicitis, with developed edematous wall thickening of the terminal ileum, cecum, and ascending colon. Superior mesenteric arteriography showed extravasation of a branch of the ileocolic artery, and embolization was performed. The patient received a random donor granulocyte transfusion on day 23 and his absolute neutrophil count (ANC) increased from 450/mm3 to 4,370/mm3 (Fig. 2). However, his absolute lymphocyte count decreased from 300/mm3 to 0/mm3. On day 35, percutaneous drainage of the periappendiceal abscess was performed under the guidance of ultrasonography. Enterococcus faecium and ESBL-producing E. coli were identified in bacterial culture of the drained abscess. On day 39 the patient's ANC was 1,390/mm3 and platelet count was 118,000/mm3 after transfusion, and he underwent right hemicolectomy and appendectomy. The appendiceal pathology revealed acute suppurative appendicitis, serositis, and cecal perforation. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and CMV-specific immunohistochemical staining of the appendiceal specimen revealed inclusion bodies at the area of acute inflammation, consistent with CMV infection (Fig. 3). Pathology of the ascending colon revealed submucosal hemorrhage and edema without evidence of CMV infection. Serum CMV real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) showed a positive result of 43,438 copies/mL on day 49 and 497,533 copies/mL on day 52. The patient had a fever of ~38.0Ōäā at that time. No evidence of CMV retinitis was observed by an ophthalmologist. After surgical resection and administration of ganciclovir (5 mg/kg intravenous, every 12 hours) for 5 days, the fever subsided. However, the patient experienced adverse effects to the ganciclovir treatment, including neutropenia, nausea, and vomiting, and was subsequently switched to foscarnet therapy (60 mg/kg intravenous, every 12 hours). CMV DNAemia by PCR revealed negative conversion after 24 days of antiviral therapy with ganciclovir and foscarnet. On day 79, the patient was discharged without complications.

CMV disease development is rare after chemotherapy other than HSCT; however, the risk of CMV disease is increasing with the use of chemotherapies that suppress cell-mediated immunity [1]. Our patient had acute lymphoblastic leukemia and showed persistent lymphopenia as well as neutropenia. Additionally, his absolute lymphocyte count continued to be < 500/mm3 throughout hospitalization. These factors appear to have contributed to development of CMV disease. While granulocyte transfusion from a random donor could be considered a risk factor, the patient's right lower quadrant pain and sustained fever presented prior to the granulocyte infusion. In this case, it is unclear whether the granulocyte infusion was a predisposing factor for development of CMV appendicitis.

There have been cases of CMV pneumonia associated with chemotherapy reported in Korea [2,3]. However, to our knowledge this is the first report of appendicitis due to CMV infection after chemotherapy. We also detected E. coli and E. faecium in blood and/or the appendiceal abscess simultaneously. In this patient, CMV appendicitis may have been accompanied by neutropenic enterocolitis. The general problem of reporting copathogens together with CMV in CMV disease is well known. In this case, E. coli and/or E. faecium appeared to be the true pathogens while CMV was considered an 'innocent bystander.' However, CMV disease is defined by identification of clinical symptoms with demonstration of CMV infection (by culture, histopathologic testing, or immunohistochemical staining) in a biopsy specimen. The diagnosis of CMV disease in this case was confirmed by H&E and CMV-specific immunohistochemical staining of the appendiceal specimen, revealing inclusion bodies at the area of acute inflammation. The diagnosis was also supported by the identification of CMV DNA in the patient's blood using RT-PCR. Blood-based monitoring for CMV by antigenemia assay or detection of viral DNA or RNA has been used for patients who have undergone allogeneic HSCT or SOT [4,5]. However, whether the detection of CMV in blood is a predictive factor for CMV disease in a non-allogeneic HSCT setting has not been demonstrated [1]. While screening of asymptomatic chemotherapy patients may not be considered cost-effective, the significance of viral pathogen detection in symptomatic leukemia patients after chemotherapy-even in the presence of other pathogens-is underscored by this case.

Currently, the definitions of CMV infection and disease are focused on the transplant recipients. However, this case demonstrates that not only HSCT recipients or AIDS patients but also acute leukemia patients can develop CMV disease during treatment with chemotherapy. Physicians should consider the possibility of CMV disease, especially when the patient presents with suppressed cell-mediated immunity, such as prolonged lymphopenia. The development of recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of CMV disease in leukemia patients who did not receive HSCT would complement existing guidelines.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print